Body Matters: Take Care to Avert Musculoskeletal Injuries

Body Matters: Take Care to Avert Musculoskeletal Injuries

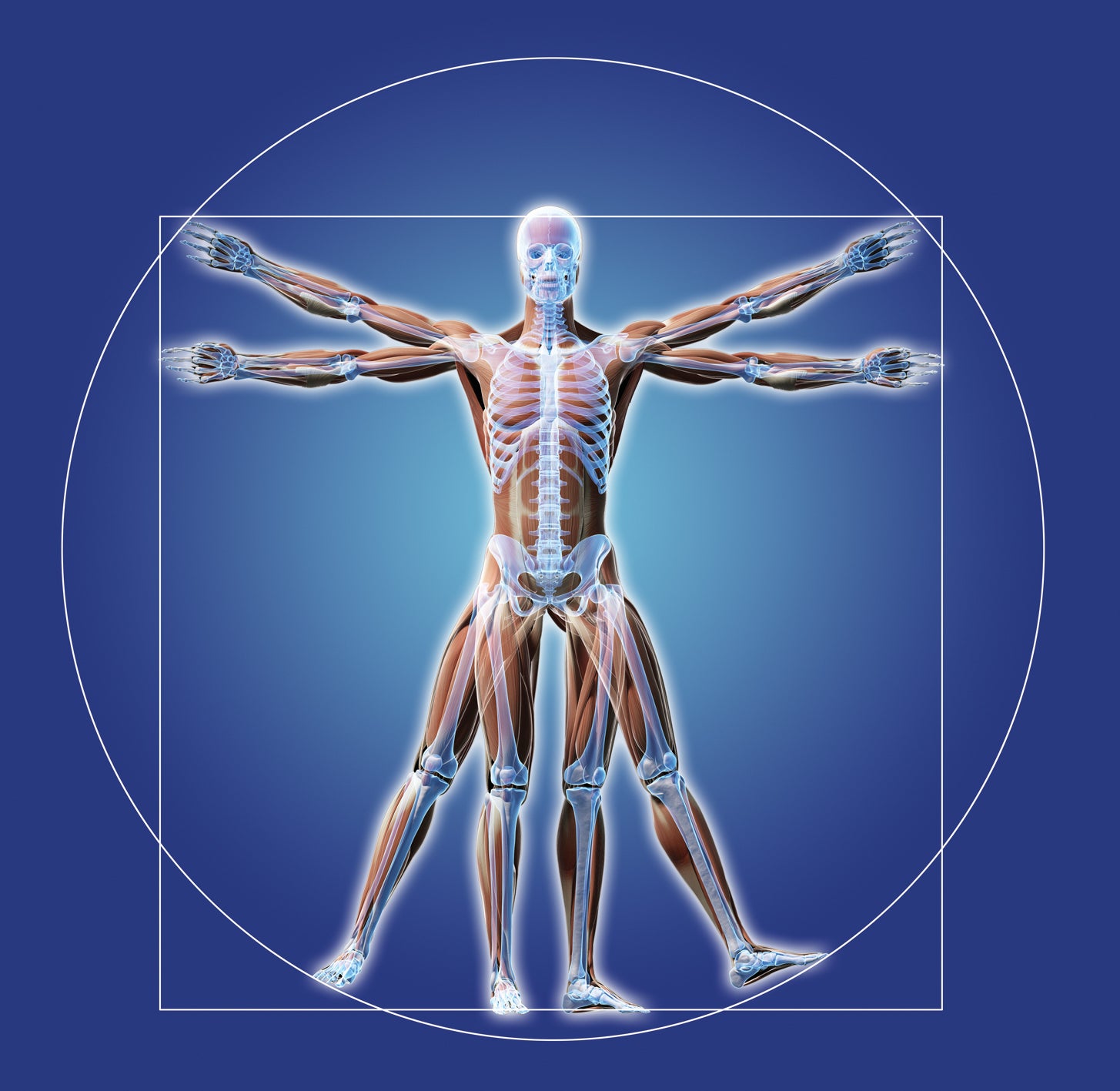

It’s said that readiness wins wars, but the ability to define and align resilience in each soldier is dramatically influenced by the demands placed upon the human body.

One of the greatest challenges facing modern warfare is the exacting cost of musculoskeletal dysfunction. What’s known as disease and non-battle injury results in significantly greater reductions to our nation’s fighting forces than combat incidents, then-Maj. Gen. James Peake wrote in the April 2000 issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. The Bone and Joint Decade Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health has identified disorders in this area as a major cause of morbidity worldwide.

With respect to the life of a soldier, who typically functions under heavier, more unrelenting and consistent loads than does a civilian, a virtual perfect storm is created resulting in even greater occurrence of musculoskeletal injury and long-term debilitation risk. When considering the inevitable acute injuries and countless other musculoskeletal conditions that adversely affect the health and readiness of our troops, musculoskeletal issues account for more than any other single diagnosis, according to the National Institutes of Health. Efforts of prevention and treatment will always be critical, but never enough to complete the triad necessary to reduce reliance on a reactivity that robs readiness of its power.

A salutogenic model of health, or the creation of health, as a way to embed the awareness, education and access necessary to lead to better outcomes under these burdens of such stressful and complex situations, is required.

These issues are not just structural. There are mental, chemical and emotional factors that tip the balance between success and failure of the mission that is sustainment of human health. There are no easy or immediate answers when it comes to the dynamic nature of the body but unless all factors are considered, examined and supported, there is no win here.

The Way You Carry Yourself

It’s true that active investigation into ways to lighten the burden on the knees and backs of those in service is logical and necessary, as is reassessing each job a soldier is asked to do to maximize fluidity and strength in function. However, allostatic load, or wear and tear that builds in the human body over time, is also influenced by an adaptive physiology that feeds on the impact of stress hormones, nourishment and individual thought processes.

There is a science and an art to the creation of resilience in each soldier. The inherent differences in reasoning, physiology, structure and function in all of us demand a comprehensive approach.

With readiness as the primary objective for soldiers, it’s inherent that cortisol, or stress hormone, levels will be increased. That fight-or-flight mechanism in our soldiers ensures mission success but over long periods of time, that response suppresses a natural feedback loop meant to control it. Such chronic impact affects REM sleep; decreases immune function; and increases the formation of fat around the abdomen, face and trunk. It also challenges the way the body metabolizes blood sugar and increases spinal muscle degeneration.

This deconditioning of the integrity of the soft tissues around the spine and remainder of the joints in the body leads to increased risk for injury and deterioration. Stress hormones are known to cause heart disease, cancer, hypertension, depression, obesity and diabetes. The question becomes: How do you efficiently measure, monitor and enhance the stress response while simultaneously mitigating the effects of it? The nature of the job isn’t going to change, but the way this critical component is addressed can be.

Proof Is in the Pudding

Each of us is on a diet of sorts. We make choices all day, every day about whether we’re going to feed health or systematically destroy it. Soldiers may be limited, however, by sheer access to nourishing whole foods and faced with having to simultaneously overcome inherent challenges in their bodies because of the job. Stress hormones drive addiction to foods that provide quick and easy energy, but empty calories.

To further complicate nutrient needs, gut health may be disrupted as a result of exposure to pathogens, poor-quality foods and stress. The potential disruption of an appropriate gut flora or microbiome environment is also a risk. This is a problem because science is clear that the bacteria in our gut not only drive our food choices, but a direct link exists between gut health and both cognitive and emotional function. The majority of serotonin, our internal “happy drug,” is also made in the gut.

We must change the way soldiers can access nourishment and their views on what nourishment is. Key nutrients are required for musculoskeletal health and well-being in general. Possessing even a cursory awareness of what these nutrients are, why they’re important, and how they make it possible for a soldier to be able to function and win can make a difference.

The challenge is addressing how people learn, the level at which they learn, and what drives the likelihood that those efforts will result in adherence to some type of positive health regimen.

It could be argued that soldiers have a fiduciary responsibility to protect the investment made in them and to honor the trust they receive to be able to perform their duties as required. It may also be fair to acknowledge a responsibility to ensure a true shared decisionmaking process when it comes to health care. This is achieved by providing patients with appropriate and meaningful education materials in an environment that encourages open dialogue.

The National Institutes of Health found that the experience of pain, a major component of musculoskeletal dysfunction, has a highly variable nature influenced greatly by the emotional and cognitive context of the pain. We simply don’t know why a sprain may heal in a few weeks in one person but cause disabling chronic pain in another. Ensuring that the pain cycle is appropriately and individually assessed, disrupted and supported through the use of nourishment, musculoskeletal health care and stress management are crucial.

No Absolutes

In a time of an ever-shrinking fighting force, there’s a call to think outside the typical box of solutions to redefine how we can support the framework created by now-retired Lt. Gen. Patricia D. Horoho in the shift from a health care system to a system for health in the Army. With no absolutes in the field of health care, we look at what creates the most effectiveness at the best cost with the lowest risk using the latest evidence.

It’s a dynamic system that requires flexibility and tactical patience. Intervening early and often, defining the best levels of intervention and even enhancing the way the health of new recruits is assessed may help change the impact of musculoskeletal dysfunction on the warfighter.

Awareness, education, and access to information and resources to support not only structural care but enhancements in stress management, nourishment and cognitive support through health literacy matter a great deal.

Ultimately, there is no simple answer for how to stay ahead of the game when it comes to the way musculoskeletal health can take a soldier from the fight.