Picture this: You are at a movie theater and realize there are only three empty seats. One is in the front row, one is in the middle, and one is in the last row. Which seat should you choose? Is one location better than the others and if so, why?

It is amazing how many decisions a person needs to make to choose the seat that would best suit their needs. The fact that a military area of operations is called a theater is not lost with this analogy. Let’s explore the seats and identify why the lack of a strategic vision can impact one’s world.

If you sit in the front row of a movie theater, you can see the screen—and that is about all. Once the movie starts, it is as if you are in the action. The characters onscreen loom larger than life, almost forcing you to look at the screen and nowhere else.

In the middle seat, your perspective changes. Not only can you see the screen where all the action takes place, but you have a wider view of what is going on around you. You are able to see the exits. You are able to see other people in the theater, and you can see their reactions to the story portrayed on the screen. Their reactions might actually impact your interpretation of the film. However, you don’t see the big picture. You are not able to see or judge what is happening behind you unless you actually turn around.

A seat in the last row gives you the biggest picture of all. You can see the screen and all the action it contains. You can see all the exits. You can see everyone who enters and exits the theater. You don’t have to look behind you because there is nothing behind. By sitting in that last row, you gain strategic vision.

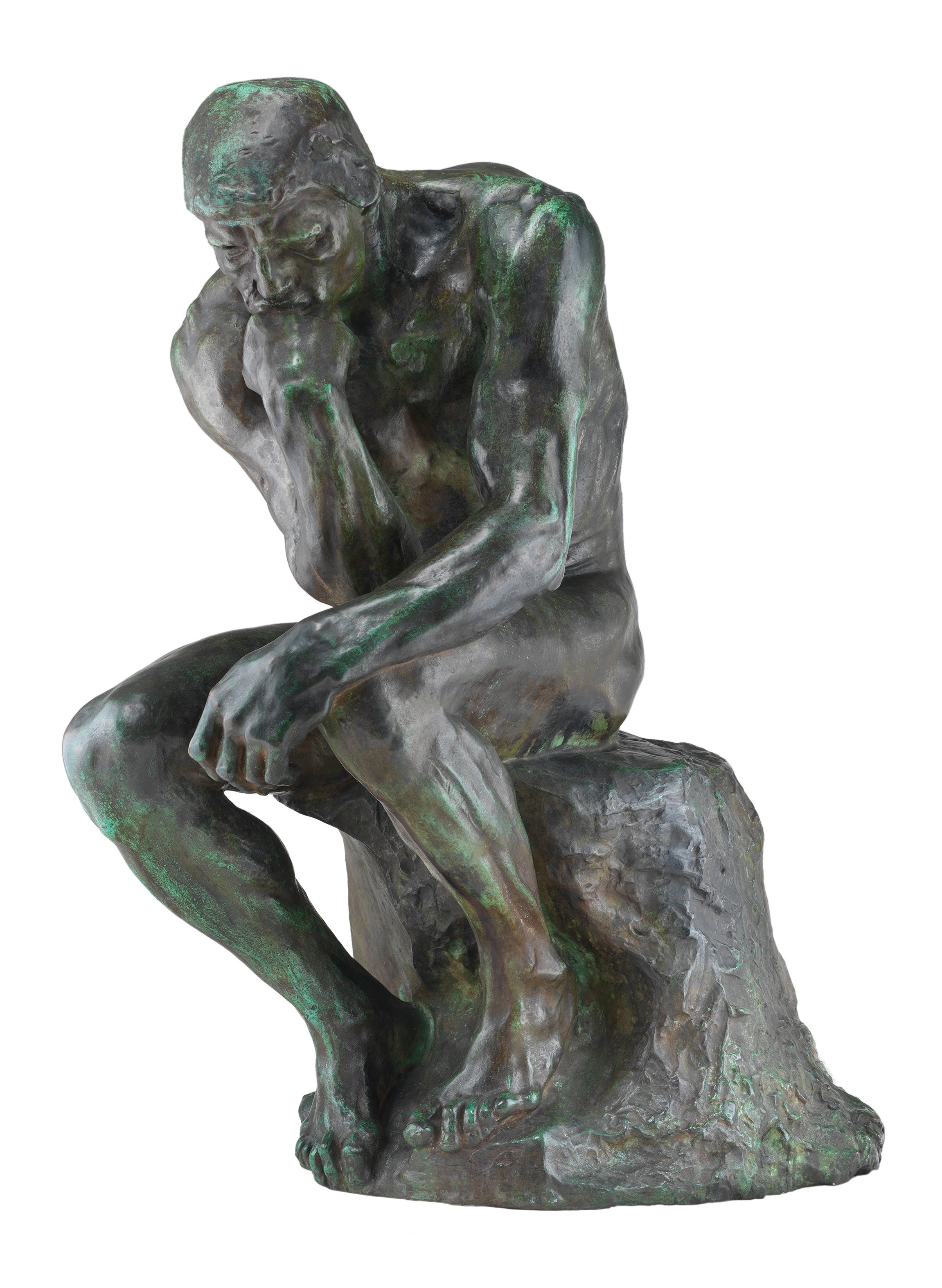

Strategic Thinking Defined

Strategic thinking is the act of pondering, analyzing and identifying the relationships among various components in a complex system. Strategic thinking enables people to develop effective plans. It helps prioritize and identify risks and potential opportunities and provides guidance for long-range planning.

Gen. David G. Perkins, in the Army Operating Concept “Winning in a Complex World,” laid out the strategy and concepts that must be explored in order to accomplish that goal. This strategy is a big-picture vision of where the U.S. Army must go to accomplish its mission. It is the epitome of strategic thinking.

Does sitting in the last row guarantee that you will see the big picture? No. You can be sitting all the way in the back and still focus your attention on only one thing. The strategic vision comes only if you choose to look at the whole theater.

How does one become a strategic thinker? Are strategic thinkers born, or are they developed? Is there a method in Army education and training that specifically addresses the skills and knowledge required to be an effective strategic thinker?

Move Away From the Action

Further back and further up. This concept tells the thinker/observer that in order to more completely understand circumstances, effort is needed to figuratively move away from the action to see it more in its entirety. One must realize that most problems are three-dimensional. The further-back portion looks at a problem within one dimension, but from multiple perspectives within that dimension. As a result, you must use the connected concept: further up. It is the deliberate, purposeful approach to look at problems at multiple levels.

This principle informs the thinker of the need to get the largest view as possible of an entire operation before proposing or implementing a solution to any given problem. Teaching people to step back and step up is a skill that can be taught in a schoolhouse. Interactive multimedia instruction is an educational strategy that can be used to teach this skill.

The onion principle. Nothing is ever as simple as it first appears. It is necessary to look at the multiple layers of a problem. There are always problems within problems; strategic thinking requires the ability to peel back the multiple layers that make up a problem. This principle is easily taught through scenario-based or outcome-based education. It can be taught in the schoolhouse and also using interactive multimedia instruction.

The multiple component principle. Another analogy can be used to explain this concept. When I (Ferguson) was young, I always wondered how things worked. I often took things apart and then reassembled them. I found that I was pretty good at doing that until I took apart my dad’s single-lens reflex camera. It was easy to disassemble. The problem was trying to put it back together. As I took it apart, I discovered many things about cameras and lenses. I learned some things about gears and mechanics. I learned all the specific elements that made up the camera and how they were used.

Unfortunately for me—and for my dad—when I was done putting the camera together, there were pieces left over. These pieces were in some way essential to the camera working because it never worked properly again. I kept telling my dad I could fix it and kept taking it apart and putting it back together, but I never figured out the right combination.

The multiple component concept focuses on the skills of analysis. Analysis means you can identify components of a system and find or understand the relationships among those components. In strategic problem-solving, you must know how to disassemble a dilemma, but you must also be able to put the parts back together in a combination that gives you the desired effect.

Person-to-Person Works Best

Multiple component theory introduces students to the need for a team-based approach to solving problems. Following the concepts introduced by the Army Learning Model, collaboration among individuals can be achieved more easily in a resident environment where students interact in real time. Although some technologies allow collaboration from remote locations, person-to-person interaction seems to be the best approach for teaching this skill.

The crystal ball principle. This is an exercise in imagining future scenarios. For any given problem, there are multiple solutions accomplished through many potential courses of action. Some will be better than others. The crystal ball exercises the ability to recognize possible futures based on the many courses of actions that might be taken. Accurately predicting outcomes is a skill that requires experimentation and modeling.

This skill is learned in the arena of scenario-based education, which can be conducted in a classroom through written scenarios or during field exercises using role-playing. Collaboration is an excellent tool to see the possible futures of many courses of action. Courses of action are proposed by groups collaborating based on the futures posited by these groups. The Army uses the crystal ball approach during field training exercises at the tactical level.

The contingency principle. Have a plan for every possible imagined future. There are times when a future has been imagined but is thought to be so unlikely that a plan to solve its problems is never created. Failure to plan for every contingency can be especially costly in lives and treasure. Contingency planning is best taught through scenario-based education in residence courses or in field training exercises.

Strategic thinking can be taught. More importantly, it can be learned. That means that although there might be natural strategic thinkers, the rest of us can learn it and use it to better ourselves and our organizations.