Warfighters wielding the most powerful weapons in the world—their brains—are working in a seemingly unremarkable building on the grounds of Fort Detrick in Frederick, Md. They are the uniformed and civilian scientists and support staff of the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, and they protect and defend soldiers against all enemies biological.

“The easy way to look at it is, we deal with things that kill you,” said Randal J. Schoepp, applied diagnostics branch chief at the institute, known as USAMRIID.

That explains why the institute is playing only a minimal role in working to find a vaccine for the Zika virus. The institute is conducting a few small studies, but Zika “is not in our wheelhouse,” Schoepp said. Although Zika can make people sick, “it’s not going to make that many people sick,” he said. About 10 percent of those who are exposed to Zika actually become ill.

“And it’s not going to kill” soldiers, he said. “Aside from the microcephaly aspect,” a condition where a newborn baby’s head is much smaller than normal because of damaged brain development, “it’s not that bad of a virus.”

Ebola, however, is that bad of a virus. The two-year wave in West Africa that began in March 2014 was unprecedented in magnitude and scope, said Travis K. Warren, principal investigator in the molecular and translational sciences division of USAMRIID. During that period, more than 28,600 cases of the hemorrhagic fever virus were reported in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization. Approximately 11,300 people died.

“West Africa experienced a terrible epidemic,” said Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “What’s less well-recognized is that the world avoided a global catastrophe.”

USAMRIID played a key role in containing the health crisis, which had “significant humanitarian, economic, political and security dimensions,” said then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Martin E. Dempsey.

Research by the institute led to a diagnostic test, or assay, for Ebola infections while the Army scientists rigorously continued investigations into therapeutics to treat, and vaccines to prevent, the often-fatal disease. It’s not a question of whether there will be another Ebola epidemic, said Maj. Anthony P. Cardile, an infectious disease physician at USAMRIID, but when. “It’s just a matter of time,” he said.

Lab Coats on the Ground

USAMRIID stood up in 1969 to protect warfighters from biological threats and investigate disease outbreaks and other public health crises. Its scientists have been at the forefront in making strides against deadly menaces such as anthrax, botulism, plague, ricin, and hemorrhagic fever viruses such as Ebola.

“While they are low incidence, they have extremely high consequences,” said David A. Norwood, chief of the institute’s diagnostic systems division.

Hemorrhagic fever viruses damage the organs and immune system and can lead to uncontrollable bleeding. Most of these viruses are zoonotic, which means they exist in animals and can infect humans. Rodents, ticks and mosquitoes are the main carriers of many hemorrhagic fever viruses, but the natural host of Ebola has not yet been confirmed, according to the CDC.

Scientists believe that in Africa, people became infected first by handling wild animals hunted for food, or from contact with infected bats. The virus then was spread person-to-person through direct contact. It is fatal in more than 50 percent of all cases, though the statistic was as high as 90 percent at the beginning of the latest crisis.

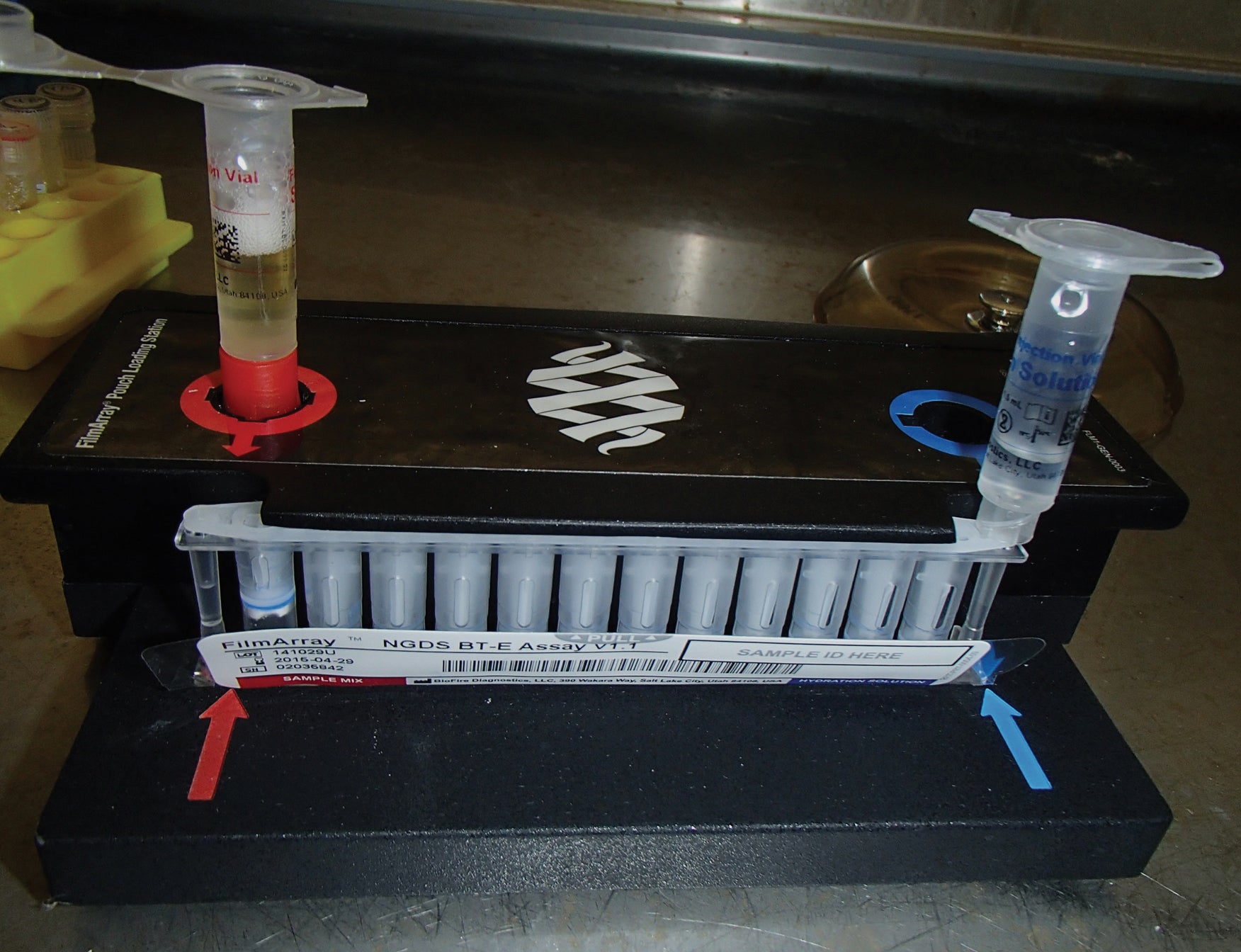

The Ebola Zaire strain, one of four known strains of the virus, was the culprit in the West Africa outbreak. When the crisis began unfolding, a small team from USAMRIID was already on the ground in Sierra Leone with prepositioned assays, working on a project on hemorrhagic fever virus identification and diagnostics. They immediately volunteered to start testing samples from sick people, Schoepp said, to determine whether it was Ebola or another virus that was making them ill.

After several months, as the disease spread throughout the region, a group from the CDC arrived in Sierra Leone to continue work there. The Army team turned its focus to Liberia, establishing an Ebola virus diagnostic laboratory at the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research (LIBR).

‘Medical Diplomacy’

For the next two years, USAMRIID teams of two and three people rotated in-country every three weeks, working 10-hour days seven days a week to test blood samples and also train five LIBR staff members to do “this really complex and dangerous work,” Schoepp said. “It’s capacity building, or medical diplomacy. That’s the way the Army does things.”

The USAMRIID team tested over 32,000 samples. “At the height of the outbreak, we were getting up to 120 samples a day,” said Schoepp, whose total in-country time was about six or seven months, and “90 percent of them were positive, really positive.”

Despite less-than-state-of-the-art equipment and safety precautions—the researchers wore multiple pairs of disposable gloves that they taped to protective suits instead of the highly specialized, encapsulating “space suits” with built-in gloves that are usually worn in the lab when dealing with dangerous toxins—“we never had a single fever watch, not a single potential exposure,” Schoepp said, adding that the work was grueling, but also gratifying.

“I’ve trained my entire life to do this type of work,” Schoepp said. “Other people with my experience may never get to go on an outbreak, let alone the largest Ebola outbreak in human history.”

Validated for Canines

Back in the U.S., Army researchers worked with the Food and Drug Administration to quickly get an emergency use authorization for the assay that was being used in Liberia. With approval granted in record time of just under a month, “It was the first assay that was developed for human testing in the United States on U.S. citizens,” Norwood said. That assay was used in state public health laboratories throughout the U.S. as well as in DoD labs all over the world.

Researchers also proved the assay would work in diagnosing Ebola in canines as the Army considered deploying military working dogs with their units when it began making plans for Operation United Assistance, deploying about 2,800 troops to Liberia to set up mobile testing labs and provide engineering and infrastructure support, among other duties.

Ultimately, the military dogs weren’t deployed. But the assay was put to good use after a dog-owning nurse in Texas contracted Ebola from one of her patients, a Liberian man who was visiting family in the Dallas area when he became ill and subsequently died. (The patient, Thomas Eric Duncan, was the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola in the U.S.)

“There was concern over what to do with this dog who had been in close proximity and potentially exposed to Ebola,” Norwood said. CDC and Texas public health officials agreed to send to USAMRIID blood samples from the nurse’s dog, Bentley, while he was quarantined for 21 days. Testing confirmed Bentley had not been exposed.

“The good news is that the nurse survived,” Norwood said. “After she was released from the critical care unit, she was reunited with Bentley.”

In contrast, around the same time a nursing assistant in Spain contracted Ebola from a missionary who had been in West Africa. The nurse survived, but her untested dog was euthanized as a precaution.

‘Mammoth Process’

When the emergency in West Africa began, no therapeutics existed that fit the necessary criteria for use, including a ready supply and data regarding efficacy and safety. Cardile, who deployed to Liberia with the 1st Area Medical Laboratory to support the U.S. response, said there were “fantastic efforts” by outside groups working with the Army researchers to bring therapeutics to clinical trial. But by the time they were able to get the approvals to do so, the outbreak was winding down.

“It’s a mammoth process to go through,” Cardile said.

Still, “we screened tens of thousands of compounds and have a very strong lead candidate” for a therapeutic “that emerged from that,” Warren said. “And we have additional compounds that we are actively pursuing right now.”

Additionally, “We are building … capability to respond more quickly to another outbreak, whether it’s a virus we’re familiar with or something new,” Cardile said, adding that USAMRIID is focusing on medical logistics planning and preliminary conversations with government and medical officials in East Africa because “that’s where we feel there most likely will be a future outbreak.”

“Everything would be essentially preprogrammed so when there’s an outbreak, we could just hit ‘play,’” Cardile said.

Additionally, several Ebola vaccines are in various stages of clinical trials, said John M. Dye Jr., branch chief of viral immunology. “Pretty much every vaccine that is currently being assessed for FDA approval has been through USAMRIID at one point or another,” he said. “They were either developed or tested here.”

* *

Zika Vaccine Is Focus of Army Researchers

Scientists at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research are working on developing a vaccine against the Zika virus. One candidate has progressed to the stage of clinical study in nonhuman primates, according to the Army, and officials are hopeful that human trials can begin this year.

“We started to conceptualize the development of the Zika vaccine actually a couple of years ago,” said Col. Stephen Thomas, an infectious disease physician who is leading a team of about two dozen researchers at the institute, located in Silver Spring, Md.

But with the spread of the virus accelerating in some parts of the world, that effort has taken on new intensity, and “we very, very quickly started to conceive animal studies,” Thomas said.

The Army initiative is part of a broader DoD effort under which several military labs are getting $1.76 million in extra funding to expand Zika virus surveillance worldwide and assess the potential impact of the virus on the health and readiness of deployed U.S. service members, officials said.

Zika is spread through the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. The common symptoms—fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes—are usually mild and last several days or a week, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But the unborn babies of pregnant women who become infected can develop microcephaly as well as other severe fetal brain defects, the CDC says.

New vaccines normally take up to a decade to be licensed, but Thomas said a potential Zika vaccine may move more quickly. “I don’t think we’re looking at the normal timeline,” he said. “We’re in the middle of an epidemic and an outbreak that’s taking a significant toll on the affected countries.”

As of early April, 4,905 confirmed cases and almost 195,000 suspected cases had been reported in 33 countries in the Western Hemisphere, according to the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch.

Thomas said the virus is “emerging” as a DoD health issue: Four soldiers and about a dozen other members of the U.S. military community were recently infected by Zika after traveling to Central or South America.

Since the virus is most prevalent in that part of the world, troops deployed to areas in U.S. Southern Command are most at risk, he said.

—Chuck Vinch

* *

Three Steps of Testing

Any therapeutic or vaccine must proceed through three steps before proceeding to FDA approval for a clinical trial in humans, Dye said. “First, does the vaccine work in a petri dish? Then, does it work in rodents? The final step is, is it efficacious in non-human primates?”

The FDA considers data from animal studies when it’s too dangerous or otherwise not possible to conduct initial testing in humans—and this is the stage that can become uncomfortable.

“It’s personally painful doing those types of studies,” Dye said. “I have a 5-year-old and a 3-year-old at home. I see a lot of the same tendencies in my non-human primates” that he sees in his children. “When I do a monkey study, I’m a miserable person at home.”

“It wears on you. It can’t not,” he said. “If it doesn’t wear on you, you shouldn’t be doing the work.”

However, “those of us who do it, we’ve come to the understanding that we believe it’s for the greater good,” he said. “I’ve made my peace with it, that in order for me to help humanity, this is what I need to do for this particular virus.”

The institute’s animal research laboratory has been certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Most of the veterinarians are active-duty Army, Dye said. In addition, many of the veterinary technicians are retired or former Army whose skills are highly prized.

“They’re accustomed to this environment and they understand the Army system, which can be imposing if you’re not already familiar,” Dye said. “They are very specialized, so they are a valuable commodity.”

Safety and Security

The Army scientists’ work with toxic viruses takes place inside containment labs with the highest safety and security measures possible. There are strict protocols regarding entrances, exits and emergencies, said David Harbourt, the institute’s biosafety officer. All employees must complete a three-day, intensive course on protocol before they’re cleared for escorted access.

“It took me 11 months to get unrestricted access” to the biosafety level 4 labs, Harbourt said.

Additionally, “people go through extensive screening and background checks to make sure they’re qualified,” he said. They also undergo a thorough medical evaluation “to make sure that they’re fit for duty” to work inside the laboratory environment, he said.

A new building for USAMRIID is under construction at Fort Detrick. The workforce will begin moving into the $650 million facility in 2017. Meantime, the Army’s cutting-edge research continues.

“I can literally walk down the hallway and talk to the preeminent toxicologist of the world,” said Dye, a virologist. “I can walk down the other hallway and talk to … the biggest anthrax researcher in the world. This is an amazing work environment.”