September 2016 Book Reviews

September 2016 Book Reviews

New Standard for Senior Leader Biographies

Jacob L. Devers: A General’s Life. James Scott Wheeler. University Press of Kentucky (an AUSA Title). 616 pages. $39.95

By Col. Gregory Fontenot

U.S. Army retired

With the publication of Jacob L. Devers: A General’s Life, retired Col. James Scott Wheeler has closed a serious gap in the historiography of the U.S. Army during World War II. Equally important, he has redressed an imbalance in historical assessment of Devers’ career and leadership in combat.

Until recently, the only biography of Devers merely summarized a great soldier’s career. Devers, unlike Gens. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley, George S. Patton Jr., Mark W. Clark and Lucian K. Truscott, is not well-known. Wheeler, a retired U.S. Military Academy history professor and author of several previous works, ably delivers on his goal to give Devers “the full biographical assessment he deserves.” He does so in the context of re-examining leadership in the U.S. Army leading up to and during World War II. The result is a deeper understanding not only of Devers but also of those with whom he served.

Devers graduated from West Point in 1909. He and two of his classmates, Patton and Gen. William H. Simpson, rose to high command during World War II. Of the three, Devers arguably took a career path ideally suited to joint and combined command at the senior level.

An artilleryman, Devers served most of his career with troop units but also had a number of assignments that today would be termed “developmental.” During World War I, he led artillery units ranging from pack howitzers borne by mules to the newfangled motorized artillery. He honed his skills as a trainer and organizer while preparing units to deploy. He developed a reputation as a problem-solver in managing projects and resources.

Ultimately, he came to Gen. George C. Marshall Jr.’s attention as an operator comfortable in joint and combined operations. In June 1940, Devers pinned on his first star. That summer, Marshall assigned him to work on the committee to choose sites for U.S. installations in the Caribbean in return for 50 obsolescent destroyers. Devers demonstrated insight and the ability to work with both the Navy and the British during that effort, which began the collaboration with Great Britain.

In October 1940, Marshall assigned Devers to command the 9th Infantry Division. In addition to training the division, he was to get the construction of Fort Bragg, N.C., back on schedule. With the Army moving in high gear to mobilize and develop new formations, Marshall called on Devers again. In the summer of 1941, Devers replaced the terminally ill Lt. Gen. Adna Chaffee in command of the newly formed armor force.

Wheeler’s narrative moves nearly as rapidly as Devers rose in grade. He captures Devers’ energy and zest for soldiering and soldiers. Yet this biography is not a panegyric. It is decidedly a work of professional scholarship weaving the Army story throughout.

The author also is adept at illustrating the role of personality and the culture of the “Old Army.” The Army of the interwar period could be every bit as cutthroat as some perceive the Army is today. Branch politics and intrigue were part and parcel of an Army career. According to Wheeler, Devers did not do well at politics and intrigue because of his enthusiasm and directness.

Wheeler’s case is compelling, since other historians also ascribe these characteristics to Devers. As a young officer, Devers served in Gen. Lesley J. McNair’s battery but had no qualms about disagreeing with him directly while in command of the armored force. Devers thought tank and anti-tank battalions should be assigned to the infantry divisions, whereas McNair wanted to pool them at higher echelons. McNair got his way but thought no less of Devers for his forthright objections.

Devers fared less well with Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton and Clark, all of whom were far thinner-skinned than McNair. Further, as expert Army politicians they were suspicious of Devers—and practically everyone else.

Devers ran afoul of Eisenhower innocently. Soon after Operation Torch, Marshall sent Devers to North Africa to assess operations and equipment. Wheeler argues that Eisenhower likely perceived Devers’ visit as threatening, possibly because the report Eisenhower had rendered on his predecessor after a similar visit led to that officer being sent home. Even though Devers offered Eisenhower his observations while reporting nothing derogatory about him to Marshall, Eisenhower perceived Devers as critical and never fully trusted him afterward.

Unlike Devers, Eisenhower had no difficulty sharing his negative views with the chief of staff. But Devers, to his credit, apparently never felt let down or disappointed. Later, he would openly support Eisenhower’s campaign for the U.S. presidency.

Devers continued to rise in responsibility. He took over command of the European Theater of Operations so Eisenhower could focus on the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. When Eisenhower returned to the U.K. and command of the European Theater to prepare for the Normandy invasion, Devers took over in the Mediterranean. There, he managed the combined operation in Italy and planned the assault on Southern France. He commanded Operation Dragoon/Anvil and in fall 1944 activated Sixth Army Group. There he directed the efforts of Seventh Army, commanded by Gen. Alexander Patch, and French First Army, commanded by the difficult and irascible Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. He managed this difficult Vichy officer while keeping the peace between de Lattre and the equally difficult Gen. Jacques-Phillippe Leclerc.

After the war, Devers commanded the Army Ground Forces before retiring. He lived until age 92, contented despite his relative lack of fame.

Wheeler is sympathetic to his subject but not blindsided by him. Devers was not perfect; like those with whom he worked, he had his foibles. However, he deserved better than he got from his colleagues. Wheeler’s book sets the standard for biography of senior leaders.

Col. Gregory Fontenot, USA Ret., commanded a tank battalion in Operation Desert Storm and an armor brigade in Bosnia. A former director of the School of Advanced Military Studies and the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, he is co-author of On Point: The United States Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

* * *

Front Line Medical Care Vividly Portrayed

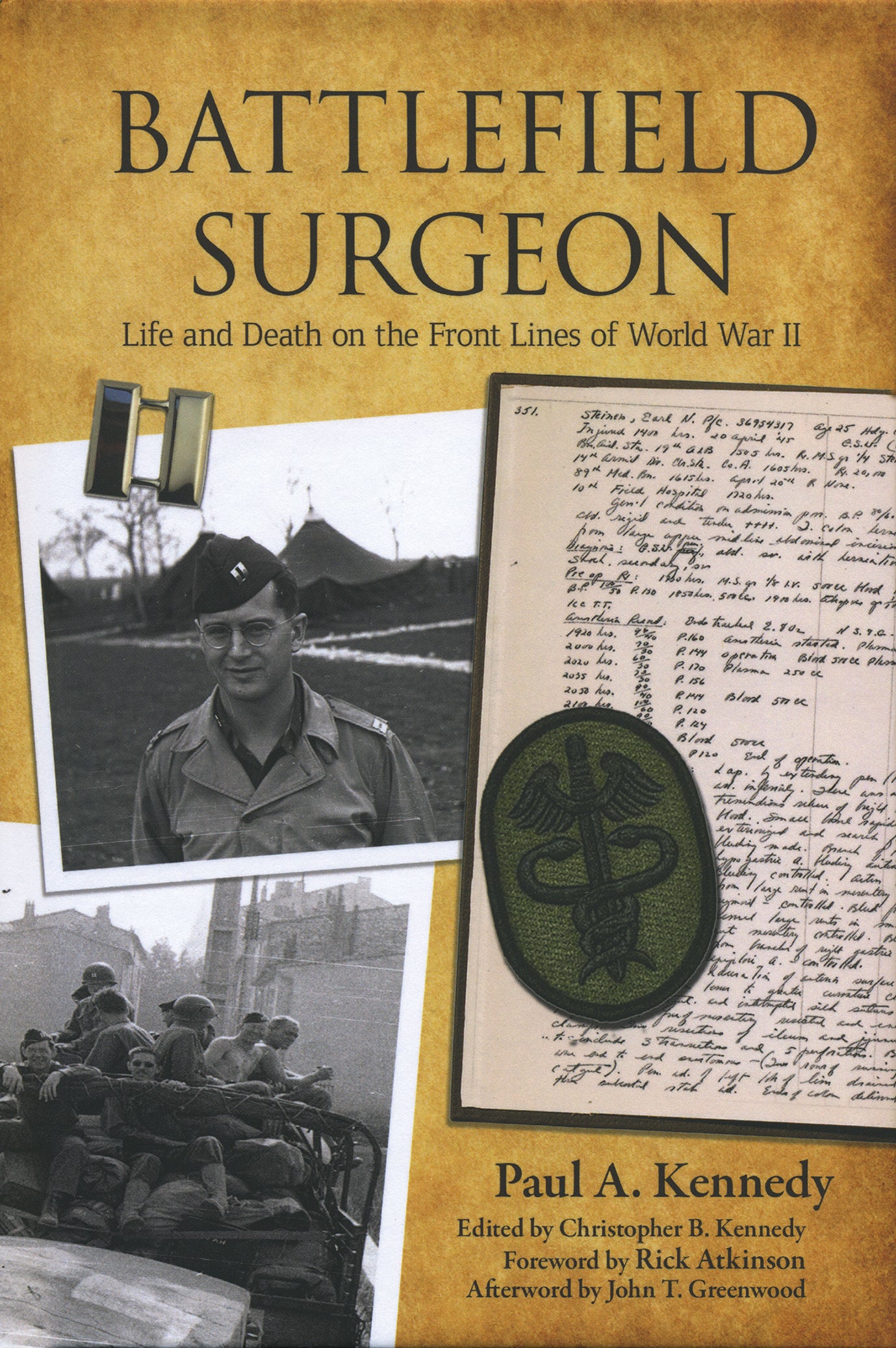

Battlefield Surgeon: Life and Death on the Front Lines of World War II. Paul A. Kennedy; edited by Christopher B. Kennedy. University Press of Kentucky (an AUSA Title). 288 pages. $39.95

By Col. Leif G. Johnson

U.S. Army retired

If I only knew then what I know now: That piece of sage perspective is why all U.S. Army Medical Department personnel—officers, NCOs, enlisted and civilians—should read Battlefield Surgeon: Life and Death on the Front Lines of World War II. Make it part of the Basic Officer Leaders Course or Advanced Individual Training, or in-processing for civilians.

Why? Because now-deceased Capt. Paul A. Kennedy’s World War II diary, medical journal, medical illustrations and photographs paint a vivid and poignant picture of what front line medical care is all about. Yes, it’s World War II and yes, surgical techniques, practices and doctrine have evolved, all for the better. But as you read this informative, educational and entertaining book, you find yourself validating the axioms of current battlefield medicine: flexibility, agility, mobility and modularity. You gain an immediate appreciation for the necessity of early, far-forward surgical intervention, stabilization and evacuation.

The 2nd Auxiliary Surgical Group, to which Kennedy was assigned, was essentially a surgical force provider for the field hospitals operating in support of front line divisions. This, more often than not, put the teams in range of enemy artillery. Analogous to today’s forward surgical teams, the 2nd Aux teams were generally comprised of two surgeons, an anesthetist, an operating room nurse, and a couple of medical technicians. They were designed to plug into one of three 100-bed platoons of a field hospital to provide definitive care.

Kennedy’s diary entries follow the war as it takes him from North Africa to Sicily, Italy and finally Germany via southern France. Most immediately, one gains an appreciation for a loving and lonely husband and father who yearns for the war to end and to be back with his family. Unfortunately, as we know and Kennedy laments, it takes three long years for that to happen.

During that time and thanks to his dedication to writing, we learn by both location and patient case how World War II battlefield medical care evolved. The fits and starts of North Africa and the “bloodying” of U.S. Army combat troops were also the proving grounds for Army front line medicine. Subsequent campaigns in Sicily and Italy fine-tuned new and innovative surgical techniques and established a viable doctrine for the employment of medical assets in support of combat operations.

Through his photographs and case illustrations, one gains insights into the character and quality of Kennedy as a man, a soldier and a surgeon. One cannot help but appreciate his innate skills at documenting each patient who crossed his operating table. He is the consummate professional as he learns and applies new surgical techniques right up to the end of the war.

His dedication and compassion to the task at hand are without question. But you also learn firsthand that Kennedy does not suffer fools kindly—though I suspect what is written in his diary was probably not transmitted orally. My enjoyment in this book could have been improved only with the addition of some maps depicting the various locations and relative battle lines.

Lastly, one has to commend Kennedy’s son Christopher, who did a superb job of collating and editing a vast amount of information into a very readable and informative book.

That Christopher chose to take on this task, we can be thankful. From the foreword by Rick Atkinson to the afterword by John T. Greenwood, the book flows beautifully. This is a fitting tribute to his dad and an amazing testament to the fortitude, compassion and dedication of front line surgical teams during World War II.

Col. Leif G. Johnson, USA Ret., served more than 26 years in the Medical Service Corps, commanding at every level from medical company to medical group.

* * *

Lots of Plot Twists With These Real Housewives

Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives: Four Women Who Influenced the Civil War—for Better and for Worse. Candice Shy Hooper. The Kent State University Press. 432 pages. $39.95

By Nancy Barclay Graves

Candice Shy Hooper has chosen an interesting way to tell a story of the Civil War. Concentrating on the wives of four of President Abraham Lincoln’s generals, Hooper presents the rise and perhaps fall of these generals through the extant letters between them and their wives.

Hooper, educated as a historian, has written for The New York Times and The Journal of Military History, among other publications. This is her first book and actually, it is four books, one devoted to each wife. Her eight years of diligent research give readers very personal accounts of Gens. John C. Fremont, George B. McClellan, William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant, with emphasis on the influence the wives brought to bear on the men themselves, or by entreaty to Washington, D.C., insiders including even Lincoln.

Hooper’s father was a hospital corpsman in the Navy, so she is cognizant of the role of the military wife in supporting her spouse. In many ways, that role has changed little since 1860. By using personal letters as her primary source, Hooper has produced intimate portraits of four generals and how their respective family lives may have influenced military decisions.

Hooper writes that Jessie Benton was introduced by her father, Sen. Tom Benton of Missouri, to Fremont, who was in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and was already well-regarded for his surveying of the Western territory. It was an introduction the senator later greatly regretted. But Jessie proved to be as strong-willed as her father and despite her parents’ opposition, Jessie and John were married, embarking on a life fast rising and equally fast falling.

Fremont was named a major general but overstepped his role by declaring emancipation in the area under his control before Lincoln had made his Emancipation Proclamation. Removed from his command, Fremont stayed in the Army but did not receive further commands. He became the darling of the emancipationists and accepted, with his wife’s encouragement, their nomination for president against Lincoln. He withdrew before the actual election. He resigned from the Army, and made a fortune on the sale of his California land. He and Jessie squandered their wealth and were forced to live on what Jessie could make from her writing. Hooper paints a very personal account of the highs and lows of their tempestuous life.

Mary Ellen “Nelly” Marcy was born in the Wisconsin territory, the daughter of a highly regarded Army officer and Western explorer. When she met McClellan, it was love at first sight for him but her interests were elsewhere. She didn’t consent to marry him until five years later but thereafter, her devotion and admiration for her husband never faltered.

Hooper empathizes that Nelly was much more interested in the social position of the general in Washington than in doing any supportive work for the troops. Through her husband’s periods of hesitation on the battlefield, she supported or even abetted him. Hooper makes a strong case that McClellan’s conversion to his wife’s Presbyterian tenets influenced his decisionmaking.

The third wife in Hooper’s account is Eleanor “Ellen” Ewing, the eldest daughter of Thomas Ewing, a prominent Ohio politician who served two terms in the U.S. Senate and as secretary of the treasury before becoming the first secretary of the interior. Thomas Ewing had taken in 9-year-old William Sherman, the son of a close friend who had died.

Sherman eventually married Ellen who, like Jessie and Nelly, was devoted to her husband despite strong differences in religion and politics and supported him through the setbacks as well as the successes of his life. Sherman resigned from the Army in 1853 and tried various occupations including banker, professor, and president of a railroad in St. Louis, finally returning to military duty after the firing on Fort Sumter, S.C.

Ellen traveled as often as possible to be with her husband, a reluctant leader who often expressed the desire to not be given a major command. He also suffered from depression. Hooper writes that when news stories said he was insane, Ellen used all her contacts to dispel these stories, at the same time writing Sherman letters of love and reassurance.

The fourth spouse that Hooper covers is Julia Dent, Grant’s wife. Unlike the large numbers of letters available for research of the first three wives, there are only five from Julia, but many from Grant to her. Julia was born with poor eyesight and crossed eyes, making reading and writing very difficult. Because of this infirmity and the fact that she was born into a slave-holding St. Louis family, she was catered to all her life.

Grant’s military rise after he returned to active duty was not always smooth. He suffered depression with his lack of confidence, but Julia was able to use her influence in Washington to get him a less demanding command. As he was promoted, he was able to have his family with him. As with the other generals, this support gave him confidence, leading to Lincoln’s recognizing him as the leader he needed. To quote Hooper,

“Julia was essential to Grant. He was the man he was—the general that Lincoln needed—because of her.”

Hooper has written a highly readable portrayal of four generals, their wives, and the times in which they lived.

Nancy Barclay Graves is an Army wife and freelance writer who lives in Arlington, Va.