December 2017 Book Reviews

December 2017 Book Reviews

Revisiting World War I Up Close and Personal

Back Over There: One American Time-Traveler, 100 years Since the Great War, 500 Miles of Battle-Scarred French Countryside, and Too Many Trenches, Shells, Legends, and Ghosts to Count. Richard Rubin. St. Martin’s Press. 294 pages. $27.99

By 1st Lt. Jonathan D. Bratten

In Richard Rubin’s first book on World War I, The Last of the Doughboys: The Forgotten Generation and Their Forgotten World War, he took readers with him as he interviewed the last surviving U.S. veterans of the war. We relived their experiences in their own words; it was the last time we would get firsthand accounts of World War I veterans. The last surviving U.S. veteran of World War I passed away in 2011 at the age of 110. Now the Great War has turned 100 and Rubin is back with another book: Back Over There. If Doughboys transported us back to France through the eyes of centenarians, Back Over There places the reader firmly in the trenches, ravines and shell holes of the Western Front.

Back Over There is essentially a guide—not only to the American experience in World War I, but to World War I in contemporary memory. As some have said, World War I is America’s forgotten war. Rubin takes us back to France to see places where Americans fought, to learn their stories and meet French residents who live among 100-year-old ruins of war. For them, the Great War is more immediate. Especially in certain places, such as the Argonne Forest, where hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops fought in 1918.

Rubin leads us through his own travel experiences, so the book reads much like a travelogue that slowly draws the reader into a historical dialogue. One moment you are stumbling with him through overgrown trenches and concrete emplacements around Bois Brule and the next you are standing with the New England doughboys in 1918 as they fight off German storm troopers. His engaging writing style draws the reader in and out of the story seamlessly.

The book alternates between a travelogue of what it’s like to tramp over forgotten and overgrown battlefields, often riddled with unexploded shells and other detritus of war, and a primer on American actions in World War I. Even novices to the Great War will be able to connect with the stories, as Rubin fully explains every action and provides context for the places he visits. The author begins with a story about his trek to find the place where the last American soldier was killed in the war. This sets the tone for the rest of the book, as the reader bemusedly joins Rubin nursing his rental car along the none-too-smooth farm roads of the French countryside.

The story turns from amusing to introspective as a local woman guides him to the very spot, marked by a bench and solitary flagpole sitting atop a ridge, where 23-year-old Pvt. Henry Gunther was killed in action on Nov. 11, 1918. Rubin’s words make one feel as if you’re standing with him on the spot, and bring a certain chill down the spine.

The work takes the reader through some of the most famous sites of the war—such as the French fortress of Douaumont, the Somme and Belleau Wood—but also to some lesser-known yet still important sites: the Chemin des Dames and its underground quarries, the Argonne Forest with its hidden secrets, and dozens of small sites where Americans engaged in life-or-death struggles. Rubin is accompanied on his forays by local experts because, as he says, each French region seems to have one or two people who know every detail of American actions in the Great War. These experts not only provide the author with the locations and stories he is searching for, but they offer amazing insight into the most minute details of the sites.

Locals also provide what is perhaps the most important aspect of Back Over There: World War I in the French memory. While many Americans have forgotten the Great War, the French remain haunted by it. After all, their land was occupied for four years and millions of its young men were killed, wounded or missing. As such, the war is still deep in France’s memory. And its people still express a fascination with the Americans who traveled across the ocean to fight for and alongside them.

Perhaps the French perspective is so interesting because it is so much the polar opposite of World War I in American popular memory. This contrast leads the reader into their own consideration of the meaning and importance of the war in American history.

Rubin follows the path of some of the well-known figures of World War I: Sgt. Alvin York, Douglas MacArthur, “Wild Bill” Donovan and Erwin Rommel. However, he is more interested in regular American soldiers, the ones who crawled through the mud of trenches and left their marks on the walls of underground quarries. Readers experience the war through their eyes, from the Regular Army and National Guard troops who arrived in 1917 to the black troops fighting alongside white outfits—even though they were not allowed the same rights back home. Readers will emerge wanting to learn more about World War I, because the author makes it clear that the war is part of our national psyche, whether we realize it or not.

Back Over There is replete with photos from the sites the author talks about, as well as copious maps that provide perspective. It will be of interest to devoted students of World War I while also being accessible to those with little to no background concerning the war. This work is an excellent opening to the centennial of America’s entry into World War I.

1st Lt. Jonathan D. Bratten is an engineer officer in the Maine Army National Guard, in which he serves as command historian. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history.

* * *

Focusing on the Grunts in Battle in Vietnam

Brutal Battles of Vietnam: America’s Deadliest Days 1965–1972. Edited by Richard K. Kolb. Veterans of Foreign Wars. 480 pages. $44.95

By Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer

U.S. Army retired

Brutal Battles of Vietnam: America’s Deadliest Days 1965–1972, edited by Richard K. Kolb, is one of a kind: The book is the first and only to offer a comprehensive U.S. battle history of the war in Vietnam in a single volume. Published by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, it is “dedicated to the 58,275 Americans who sacrificed their lives in the Vietnam War.” Kolb, a Vietnam veteran and publisher and editor-in-chief of VFW magazine from 1989 to 2016, conceived the idea for the book, selected and edited its content and wrote some 40 of the 94 chapters and “Special Features.”

The book gives readers a firsthand account of the war as seen through the eyes of front-line troops. The infantrymen, affectionately referred to as grunts, totaled approximately 12 percent of those who served in Vietnam, but accounted for 70 percent of those killed in action, Kolb says. The grunts, along with their battle buddies, the combat medics/corpsmen and forward observers, were the ones “beating the bush” during the war. Add the combat arms mix of helicopter crews, field artillerymen, armor crewman and combat engineers and the percentage increases to 87 percent of the Army’s hostile deaths in Vietnam.

The battles included in the book will no doubt shock the reader with their ferocity and brutality. They will invoke memories of hardship and sacrifice among our Vietnam veterans, memories of battles fought and friends lost a half-century ago. Memories of the time between the battles filled with unexpected encounters with the enemy. Firefights, ambushes and booby traps taking a deadly toll. Long, exhausting days and sleepless nights. For the generation too young to have fought or too young to remember, this book will offer a glimpse of the war that divided the nation.

The book is filled with accounts of incredible courage on the battlefield. Acts of courage and valor on the battlefield that became almost commonplace. The acts of those who received the nation’s highest awards are part of the story. The thousands of acts of valor that went unreported because “they were just doing their job” are also part of the story. It’s about the generation of young Americans dealing with the all but impenetrable jungle, oppressive heat, stress, fear and an elusive enemy in a faraway place. Ordinary young men performing extraordinary acts of bravery.

The focus is on the selfless service and sacrifice of those who fought, bled and died in the war. It is not about politics, history or opinions about the war. It’s about the warrior. Some volunteered and some answered the nation’s call. All gave some, some gave all.

Brutal Battles of Vietnam is an important book. The words are provided by the men who fought the battles, and it is filled with photographs of the battlefield taken during or just after the fight. It includes interesting profiles of the troops that just might surprise you. This is a must-read for professional and amateur military historians, for Vietnam veterans and their family members, and anyone who seeks to understand that war on the other side of the world and the men who fought there.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars is to be commended for this impressive contribution to the understanding of the war. The VFW has partnered with DoD and a grateful nation to help thank and honor our veterans. Hopefully, this effort will help bring some small degree of closure for them.

Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer, USA Ret., held a variety of assignments with infantry, Special Forces and Ranger units during his 32 years of active military service. He is the former director of the Association of the U.S. Army’s NCO and Soldier Programs and is now an AUSA senior fellow.

* * *

Young U.S. Soldiers Sit Vigil With Saddam

The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid. Will Bardenwerper. Scribner. 272 pages. $26

By Col. Gregory Fontenot

U.S. Army retired

Will Bardenwerper’s The Prisoner in His Palace is the well-told story of the last four months of Saddam Hussein’s captivity and his execution, seen through the eyes of the “Super Twelve” who were his guards. These young military policemen from the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), and a Lebanese-American interpreter, began their vigil with Iraq’s former president in August 2006. They concluded their task when they escorted him to his final rendezvous with destiny on Dec. 30, 2006.

It appears no one saw fit to provide these soldiers with much in the way of training, or even warned them about how to cope with Saddam. It was as if they were asked to guard Hannibal Lecter in a minimum-security facility. One of the 12 recognized that analogy himself. Not surprisingly, they succumbed to Saddam’s charm. None forgot who Saddam was, but he managed to make them sympathetic to the point that some joined him for a smoke and conversation in the evenings.

While nothing terribly untoward happened while the soldiers guarded Saddam, the nonchalance with which the Army approached the task of guarding a man as evil in scope if not in scale as Hitler, Stalin or Cambodian political leader Pol Pot is remarkable. Two themes are evident in the guards’ experience. First, they perceived the irony of their task. Perhaps most ironic is that while certainly evil, Saddam proved charming and human. Second, the reader will see the inherent goodness and humanity of the soldiers who lived with Saddam in his last months.

There is a third insight implicit in the story of Saddam’s guards and that is of a general American naiveté in dealing with foreign cultures, even those we observe for a long time. By the time Saddam was executed, Americans had been observing the barbaric ways ethnically and religiously divided Iraqis often dealt with their rivals. Still, Saddam’s U.S. guards, and indeed many U.S. witnesses to television films of Saddam’s execution, found the tone unsettling. Witnesses taunted Saddam before he was hanged and the official Iraqi witnesses to the execution spat on and kicked the body of the dead dictator, something his former custodians apparently did not expect.

The translator who worked with the guards expressed the dissonance between how he came to feel about Saddam and what he knew Saddam had done. He posed the question of whether he would miss Saddam the brutal dictator. He allowed that he would not. But as to whether he would “miss sitting in the evening with him as a human being,” he answered yes.

What then do we make of our role in Iraq and our ignorance of the cultures in the region? Bardenwerper’s book should make us wonder.

Col. Gregory Fontenot, USA Ret., commanded a tank battalion in Operation Desert Storm and an armor brigade in Bosnia. A former director of the School of Advanced Military Studies and the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, he is co-author of On Point: The United States Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom and author of The 1st Division and the US Army Transformed: Road to Victory in Desert Storm 1970–1991.

* * *

Black Troops’ Contributions to Revolution

Standing in Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution. Judith L. Van Buskirk. University of Oklahoma Press. 297 pages. $34.95

By Lt. Col. Robert Bateman

U.S. Army retired

In Standing in Their Own Light, professor Judith L. Van Buskirk of the State University of New York College at Cortland takes up a historical gauntlet and meets the considerable challenges presented head-on.

The result is a serious work of academic history that explores an almost unknown aspect of American military history—the experiences of black soldiers serving in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

If, for personal, professional or historical reasons, this aspect of our history is of interest to you, then this is a vital new addition addressing an area generally ignored until now. A brief survey of the literature makes that clear.

Of the academic surveys into the experiences of black troops during the Revolution, Bernard Nalty’s Strength for the Fight devotes a whopping nine pages to the period, while Gerald Astor’s The Right to Fight gives only eight pages to the subject.

Pop historian Gail Buckley’s book American Patriots does but a little better with 10 pages, but anthropologist Robert Edgerton in Hidden Heroism devotes just three pages. Other works are much the same. And no wonder, because the challenges of reconstructing the history of black Americans in this era are monumental.

Historians, it is said, privilege the written word. Unlike oral accounts, words committed to paper at or near the time of an event come down through the decades unchanged. The problem is therefore obvious: At the time, literacy among the general population was low and among slaves and freedmen, nearly unknown.

Accordingly, there are vanishingly few collections of postwar memoirs or troves of contemporary letters written by black soldiers to their loved ones at home for the historian to mine. Because of this dearth of source material many, indeed most, of those soldiers’ voices were lost to time. Getting back to their historical truth required herculean labors.

Van Buskirk reconstructs these soldiers’ stories through a difficult and obscure source: the records left decades after the war by those veterans (or their survivors) who sought pensions for their war service in the early 1800s. In these applications, the veterans’ accounts, each supported by multiple other witnesses who could verify a veteran’s service, were recorded by government clerks.

In some 15 years since she started the project, Van Buskirk pored through thousands of such records and in the process uncovered some 500 veterans for whom she could confirm race and status.

Most of her material focuses upon two efforts to officially bring blacks into uniform: the successful raising of the 1st Rhode Island (Line) Infantry Regiment and the less productive efforts to do the same in South Carolina. It is especially with the former that Van Buskirk manages to breathe life into the story.

If there is a fault to be found here it is in the curious absence of research into what was probably the greatest area of contribution by black service members during the Revolution—the war at sea. Aboard privateers, the navies of the individual states, and the ships of the nascent U.S. Navy, black sailors were fully integrated in the ranks and employed according to their abilities, not the color of their skin.

Despite this gap, which will hopefully be filled by a future scholar, Standing in Their Own Light is a rock-solid work of academic history.

This is not a light or breezy work. Despite Van Buskirk’s considerable talents as a storyteller, she was constrained by her source materials and had to dig hard to translate fairly dry raw materials into compelling historical accounts. Regardless, this new book is a worthy addition to the specialist’s or interested individual’s library.

Lt. Col. Robert Bateman, USA Ret., served for 25 years as an Army officer. He taught military history at the U.S. Military Academy; George Mason University, Va.; and Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. He has written several books and is currently writing one about the interwar period.

* * *

Letters Home Paint Vivid Picture of War

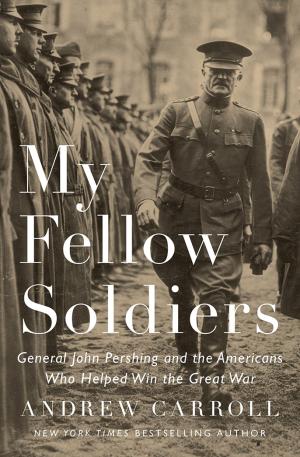

My Fellow Soldiers: General John Pershing and the Americans Who Helped Win the Great War. Andrew Carroll. Penguin Press. 416 pages. $30

By Nancy Barclay Graves

My Fellow Soldiers by Andrew Carroll is a fast-moving chronicle. It focuses not only on Gen. John J. Pershing and the Great War, but it also includes background regarding the beginning of the war, President Woodrow Wilson’s delay in committing American troops, the so-called Punitive Expedition to catch Pancho Villa in Mexico, and the personal tragedy in Pershing’s life and remarkable on-scene descriptions from people who were there.

The source of much of Carroll’s information is personal letters he gathered from family collections. On Veterans Day in 1998, his letter to “Dear Abby” asking people to send family letters to his Legacy Project garnered more than 15,000 of them. The project has since gathered over 100,000 letters, and from these sources Carroll has written several history books, this being the latest.

The public image of Pershing as a rather cold, methodical general is altered by Carroll to show that to the contrary, Pershing was a sympathetic man, a lonely man following the tragedy of losing his wife and three young daughters in a house fire at the Presidio of San Francisco while he was stationed at Fort Bliss, Texas. Only his 6-year-old son survived.

Pershing was at Fort Bliss commanding the Army’s 8th Infantry Brigade to protect the Texas territory from the raids of Pancho Villa. Europe was at war, a war precipitated by the murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife. Wilson was determined to keep the U.S. out of the European conflict. Instead, he felt it more in U.S. interests to protect the Texas territory from Mexican incursions.

As time passed, however, the Germans increased their use of submarines to sink allied shipping in the Atlantic, regardless of whether the ships were civilian or military, traveler or supply. The sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania was an enormous influence on Wilson. He could not continue to stay out of the European conflict.

Already in Europe and involved in the war were young Americans who saw glory in the French Foreign Legion. Using their letters home, Carroll has drawn an interesting account of these young men and how from their enlistment in the foreign legion came the Lafayette Escadrille, the first use of airplanes by Americans in war.

When Wilson and his secretary of war finally decided to involve America in the European war, Pershing, still in Mexico, wrote to Wilson to make sure he knew that Pershing was eager to head for Europe. It worked. Pershing was named to head the American Expeditionary Forces.

Still using the personal letters home of soldiers and officers, Carroll describes not only individual skirmishes, but overall planning by such men as Col. Douglas MacArthur, Maj. “Wild Bill” Donovan, Capt. George S. Patton, Harry Truman and others who later became stalwart leaders of World War II. How vivid becomes the Great War from these personal letters! In Carroll’s own words, “The aim in this book is to portray an overall sense of what these men and women, especially those who volunteered, lived through and felt and expressed during the war and, if they survived, in the years and decades that followed.”

In this centennial year of U.S. involvement in World War I, it is especially suitable that we should review that period. I recommend reading My Fellow Soldiers.

Nancy Barclay Graves is an Army spouse and mother of two retired Army officers.