January 2018 Book Reviews

January 2018 Book Reviews

Warrior Brothers Served Together in Vietnam

Our Year of War: Two Brothers, Vietnam, and a Nation Divided. Daniel P. Bolger. Da Capo Press. 336 pages. $28

By Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer

U.S. Army retired

Our Year of War tells the story of two brothers fighting an implacable enemy in a faraway place that just a few years earlier most Americans couldn’t find on a map. Chuck Hagel was the oldest and the first to go. At 21 he was a prime candidate for the draft. Instead of waiting, he volunteered and his name moved to the top of the Platte County, Neb., Selective Service Board list. Chuck’s younger brother Tom, wrapping up high school, would soon follow in his brother’s footsteps.

It was late 1967 and the fighting in Vietnam was about to enter its fourth year. The following year started on a high note. The news from the White House was optimistic. We were winning and leadership could see the light at the end of the tunnel. America breathed a collective sigh of relief that their loved ones would soon return. But something happened to turn everything on its head. That something was the Tet Offensive. That light at the end of the tunnel now looked more like the headlight of an onrushing train.

For the Hagel brothers, infantrymen serving in the same platoon, it meant a year of hard fighting. A year of enduring the strength-sapping heat, thrashing through all but impenetrable jungle while carrying 70-plus-pound loads on their backs. It meant days spent riding on top of armored vehicles on mine-infested roads, jumping from helicopters in hostile territory hoping to catch the enemy by surprise, and sleepless nights in ambush sites. It meant knowing every day might be the last.

Military service was in the DNA of the Hagel family. Their father, Charles Dean Hagel, served in the Army Air Forces during World War II. Charles was one of six enlisted crewmen serving on a B-17E Flying Fortress. During most bombing missions, he would man the tail gun or sometimes be up front operating the radio.

Charles took pride in his service. After returning to his home and family in Nebraska wearing sergeant stripes, he commanded the local American Legion post for years where he and his fellow veterans and their families would gather. They said the Pledge of Allegiance and carried the flag in local parades. Charles was welcomed as a hero by a grateful nation and his family.

Wartime service for the Hagel boys was never in question. Their father had served and now it was their turn. It was an opportunity to do their part and carry on the family tradition. For “grunts,” as the infantrymen liked to call themselves, the Vietnam War was up close and personal. The grunts were the ones being shot at and shooting back. And they accounted for the majority of the casualties.

The Hagel brothers worked well as a team. They had each other’s back. By the end of their year in Vietnam, they had been elevated to leadership positions in their platoon and between them they received five Purple Hearts along with their promotions. They, like their father 20 years before, would return home wearing sergeant stripes. But their homecoming would be different.

They returned to a nation divided. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy sparked further unrest. Most large cities in America, including the Hagels’ hometown of Omaha, experienced rioting in the streets. The Vietnam War had become unpopular. With the death toll increasing and no end in sight, support for the war was slipping. And some Americans blamed the veterans for a war they didn’t start. They were unable to separate the war from the warrior. The brothers were also divided. Chuck supported the war; Tom did not.

The brothers moved on with their lives. They finished college and became successful in their chosen careers. Chuck devoted his life to public service, first as a U.S. senator and then as secretary of defense. For Tom, law school was next. He wanted to stand up for those who could not stand up for themselves. He became a public defender because he strongly believed that every American deserves a fair trial.

The author, Daniel P. Bolger, served in the Army for 35 years, rising to the rank of lieutenant general before retiring. He commanded troops in Afghanistan and Iraq. He has experienced war firsthand and is uniquely qualified to tell the Hagels’ story. And he pulls no punches. He puts things in perspective. He does an excellent job describing what the Hagels experienced in Vietnam and what was simultaneously happening on the homefront. He provides insight into what senior military leadership was thinking and how it affected soldiers in the jungle. (Bolger is a senior fellow of the Association of the U.S. Army’s Institute of Land Warfare and a contributing editor of ARMY magazine.)

Our Year of War is one of the best accounts of men at war in Vietnam. It will appeal to every category of reader, and it should be mandatory reading for military leaders at every level.

Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer, USA Ret., held assignments with infantry, Special Forces and Ranger units during his 32 years of active military service. He is the former director of the Association of the U.S. Army’s NCO and Soldier Programs and is now an AUSA senior fellow.

* * *

Enigmatic Grant Undervalued as a Statesman

Grant. Ron Chernow. Penguin Press. 1,104 pages. $40

By Col. Cole C. Kingseed

U.S. Army Retired

History has not been kind to former President Ulysses S. Grant. Although numerous biographers have lauded Grant’s military acumen in the Civil War, many have characterized his presidency “as an embarrassing coda to wartime heroism.” In Grant, Ron Chernow strives to correct this misperception and paints a more sympathetic portrait of the 18th president. Chernow views his subject not only as the general who vanquished the Confederacy, but also as “the single most important figure behind Reconstruction.”

In recent decades, Chernow has emerged as one of this country’s most accomplished biographers. He is a prize-winning author and the recipient of the 2015 National Humanities Medal. Chernow’s Washington: A Life earned the Pulitzer Prize for biography and Alexander Hamilton was the inspiration for a hit Broadway musical.

As with most biographers, Chernow affords Grant high accolades for his martial success. The former leather goods clerk from Galena, Ill., had been “the mainspring of the Union effort, imposing order and giving cohesion to far-flung armies.” As a strategist, Grant was superior to his most famous opponent, Gen. Robert E. Lee, although Lee was the master tactician. In comparing the two adversaries, Chernow proclaims Grant as the “strategic genius produced by the Civil War” who “grasped the war in its totality, masterminding the movements of all Union armies.”

To his credit, Chernow does not shy from Grant’s fondness for alcohol. Chernow contends that Grant was a confirmed alcoholic with an astonishingly consistent pattern of drinking, recognized by friend and foe alike. While drinking almost never interfered with his official duties, Grant “managed to attain mastery over alcohol in the long haul, a feat as impressive as any of his wartime victories.”

It is in his post-Civil War career that Chernow makes his greatest contribution to unraveling the enigma of Grant. “It is sadly ironic that Grant’s presidency became synonymous with corruption,” the author opines, “since Grant himself was impeccably honest.” The great mystery of Grant’s administration is how this upright man tolerated some of the most corrupt officials who held public office. Perhaps Chernow is correct in his assessment that Grant was a strange amalgam of wisdom and naïveté about human nature.

With scandal surrounding his first administration, why then did Grant accept a nomination for a second term as president? Grant occasionally dreamed of returning to his farm in St. Louis, “but I consented to receive the nomination simply because I thought that was the best way of discovering whether my countrymen … really believed all that was alleged against my administration and against myself personally.” More importantly, Grant long warned that a Democratic Party victory in 1872 might overturn the result of the Civil War, degrading the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments.

In the final analysis, Chernow sees more positives than negatives in Grant’s two terms as president. It was Grant who initiated the modern national park system by establishing Yellowstone as the first national park on March 1, 1872. By his enforcement of the Ku Klux Klan Act, Grant smashed the Ku Klux Klan in the South. Small wonder that Frederick Douglass emphatically stated, “To Grant more than any other man the Negro owes his enfranchisement.” In addition, Grant was the first chief executive to confront the feminist movement as a viable political force.

Chernow concludes his biography with a detailed look at Grant’s final years, culminating with Grant’s decision to publish his wartime memoirs. Assisted by Mark Twain, Grant secured a literary offer that would assure his family’s financial success. By March 1, 1885, The New York Times ran a headline that announced Grant’s death was imminent. Summoning his last reserve, Grant completed his manuscript, days before his death on July 23, 1885.

In restoring Grant’s reputation as a general and president, Chernow has produced the most comprehensive single-volume biography of Grant. Americans remain in Grant’s debt for fulfilling Lincoln’s dream of political equality. We are in Chernow’s debt for making Grant’s story accessible to a new generation of Americans.

Col. Cole C. Kingseed, USA Ret., a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate from Ohio State University.

* * *

Patton Interpreted for Today

21st Century Patton: Strategic Insights for the Modern Era. Edited by J. Furman Daniel III. Naval Institute Press. 176 pages. $24.95

By Maj. Joe Byerly

When most people think of Gen. George S. Patton, the image of “Old Blood and Guts” or the caricature created by George C. Scott in the 1970 film Patton come to mind. The famous general was much more than that. He spent his lifetime studying war and the humanities, and even more interesting, he was a prolific writer (and poet). In addition to the boxes of notecards he kept for himself, Patton published in numerous military journals. He was a scholar and a warfighter; his example is worthy of pursuit by those who lead soldiers today.

In 21st Century Patton: Strategic Insights for the Modern Era, an edited volume of Patton’s essays written between 1913 and 1942, J. Furman Daniel III provides an introductory analysis for each of seven of Patton’s articles that offer a modern perspective for those serving today. The articles range from technical pieces such as “The Form and Use of the Saber” to more conceptual topics like “Why Men Fight.”

My favorite aspects of the book are the introductions written by Daniel. His essays are easily readable, provide historical context to each of the featured works of Patton, and then connect them to current trends in warfare. For instance, when introducing the essay titled “The Effect of Weapons on War,” Daniel discusses war’s constant nature as well as its changing character. He highlights the fact that every technological advantage in war is met with a series of countermoves that eventually neutralize that advantage, but notes, “Despite the technological advances of recent decades, this article is a sobering and enduring reminder that war is an intensely personal and human affair.”

As readers work through the selected essays, Patton’s commitment to the profession of arms is readily apparent. As Daniel points out, “Patton’s dedication to being a complete soldier resulted in a purposeful process of self-improvement. His studies allowed him to seamlessly transition between tactical action and strategic thought and contributed to Patton’s mythos as a natural warrior.” As history has shown us, Patton’s personal preparation translated to success on the battlefields of World War II.

21st Century Patton is the perfect book for young leaders serving in uniform today. Daniel’s book provides readers with the example of an officer who sought not only to improve himself and his organizations, but the greater Army as well. He accomplished this through his leadership, lectures and published articles. More importantly, Patton’s original works along with the accompanying essays show how experience coupled with self-study develop a mind that is capable of grasping the complexities of the modern battlefield.

Maj. Joe Byerly is an armor officer and executive officer for the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, Colo.

* * *

A Singular Look at the History of Special Ops

Oppose Any Foe: The Rise of America’s Special Operations Forces. Mark Moyar. Basic Books. 432 pages. $30

By Derek Leebaert

In Oppose Any Foe, Harvard University-trained historian Mark Moyar delivers an exceptionally valuable contribution to an understanding of U.S. military capabilities. Admirers of his equally impressive studies—Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965 and Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam—will see a continuity of work that distinguishes him as one of the most thoughtful of a new generation of military historians.

Moyar, a director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, applies his skills to raising provocative questions on a subject that has been drowning in snap bestsellers, ones largely written by special operators themselves. Men once known as “the quiet professionals” have built a cottage industry publishing wartime adventure stories inevitably short on analysis. Moyar, in contrast, combines the perspective of a historian with deep knowledge of his subject, having served as a professor of insurgency and terrorism at the U.S. Marine Corps University, a senior fellow at the Joint Special Operations University and a consultant for senior leadership for Special Operations Joint Task Force-Afghanistan. As a result, Oppose Any Foe is a gripping historical narrative that illuminates a distinct, finely honed way of war that has shaped America’s role in the world for nearly a lifetime.

In fact, the form of combat mastered by Green Berets, SEALs, Air Commandos and other U.S. special operators is quintessentially American. It distills the self-reliance, enterprise, technical ingenuity and distant reach originally shown by Roger’s Rangers in the French and Indian War. Before the birth of the U.S., a new relationship had evolved between a small force’s officers and men, a new strategy of long-range penetration, and an altogether new discipline of irregular combat.

The origins of today’s special operations forces, Moyar explains, stem most directly from World War II’s espionage and sabotage organization, the Office of Strategic Services. Army Special Forces then emerged nearly by accident in 1952. But the country’s initial burst of enthusiasm for special operations came later. It can be dated almost to the hour of President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration. The president had been a small-boat commander in the Pacific, and once in office he helped the commandos select equipment, such as the SEAL’s dual-outboard Boston Whaler boats and M60 machine guns. For the Army, he famously authorized the green beret itself, overriding the chief of staff. The Air Force thereafter formed its own special warfare organization. Cigar-chomping Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis LeMay harrumphed that the other services were “simply climb[ing] on the bandwagon” of the latest fad in military spending, yet in 1963 he revived World War II’s Air Commandos.

Troublingly, these deadly new capacities also introduced new forms of risk when creating foreign policy. In 1962, when journalists and Republican politicians exposed that America’s presence in Vietnam had become much more than “advisory,” Kennedy—visibly embarrassed—insisted they were not “combat troops in the generally accepted sense of the word.” To be sure. By the summer of 1963, they were Green Berets, SEALs and CIA paramilitary units. It’s a slippery slope into unanticipated entanglements, and commandos have been drawn into White House attempts at fine-tuning the planet ever since.

A dozen years after the fall of South Vietnam, U.S. Special Operations Command was created in 1987. USSOCOM has de facto become the country’s sixth military service alongside the Army, Navy, Air Force, Coast Guard and Marines (which, in 2006, established yet another spec ops capability, Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command). As foreshadowed under Kennedy, USSOCOM’s missions uniquely bridge political and military spheres in the exercise of American power, and its influence reaches through the State Department, Congress, the intelligence services, the White House and the Pentagon.

Moyar examines what’s been accomplished by nearly two decades of shadow war against an array of terrorist entities, an era that includes the nation’s failure to achieve any semblance of success in Iraq and Afghanistan. His assessment is unflinching as he examines problems of undue secrecy and bureaucratization, and as he alludes to undue military involvement in Capitol Hill politics.

With similar rigor, Moyar could have explored even tougher questions about the use of America’s special operations forces. For example: How might these units perform when confronting vastly more formidable opponents than al-Qaida and the Islamic State group that they have faced since 9/11? (Such as Russia’s Special Operations Forces Command or China’s People’s Liberation Army.) Do U.S. commandos in fact conduct “special operations” or have they become accustomed in Third World combat to exercising what are essentially higher forms of reconnaissance and raiding? Has the tail turned to wag the dog so that conventional units support Special Forces which, ironically, often possess greater resources?

Moyar’s work compels his civilian and military readers alike to confront such issues. And his rapidly flowing narrative offers a timely warning based on decades of special operations forces history: U.S. policymakers need to educate themselves on the relative strengths and weaknesses of these elite forces, and to acquire a deeper understanding of when and where these warriors should be used.

Derek Leebaert serves on the advisory board of the U.S. Army Historical Foundation. His books include To Dare and to Conquer: Special Operations and the Destiny of Nations, from Achilles to Al Qaeda.

* * *

Fighting With Bullets and Band-Aids

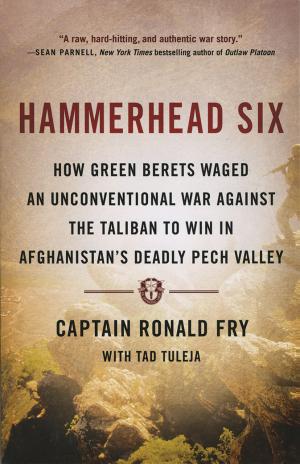

Hammerhead Six: How Green Berets Waged an Unconventional War Against the Taliban to Win in Afghanistan’s Deadly Pech Valley. Capt. Ronald Fry with Tad Tuleja. Hachette. 400 pages. $10.95

By J. Ford Huffman

Unlike other special operators—some Navy SEALs come to mind—Army captain-turned-author Ronald Fry was reluctant to “write this memoir about what our time in Afghanistan had taught me.”

Why?

“Green Berets don’t generally chronicle their adventures, as that goes against our ‘quiet professional’ ethos.”

But “out of a responsibility to share the valuable lessons we learned with the next generation of unconventional warriors,” Fry joined forces with co-writer Tad Tuleja. The resulting Hammerhead Six is—given Afghanistan’s spot on the commander in chief’s agenda—a worthwhile look at being between rocks in a hard and ancient place in 2004.

At the time, “there were not many soldiers still in the Army who had done what Hammerhead Six was doing” in the Pech Valley of Afghanistan’s Kunar Province. “Hammerhead Six” was the code name for the Special Forces unit Fry commanded.

A Special Forces unit’s role is to provide “eyes and ears on the ground” for command and to “help indigenous populations resist their oppressors.” In addition, Fry discovers that his Army and Mormon training allows him to treat Afghanis as people.

Fry’s fortitude fares well, and his assumptions about what happened a dozen years ago are timely, even prescient.

His focus is on the unconventional in an unconventional (to Westerners) place “where warlords hired their nephews out as mercenaries, where opium drove the economy, where a daughter could be offered as a gift to an American soldier, and where an everyday reality included the chance that you would be killed by a long-buried mine”—and “where military loyalty was a tenuous commodity.”

Yes, out of respect a “shura” leader offers his daughter to the married Fry, who diplomatically declines.

His team establishes trust while dispensing discipline, friendship and medical aid. “Band-Aids and penicillin could also break down walls,” he writes. The work of Operational Detachment Alpha 936 catches the attention of the news media, including 60 Minutes, and subsequently, the generals.

Not that Fry needs help getting noticed. When an IED blast renders one vehicle undrivable, a staff officer radios Fry that the Army needs “to retrieve the asset and study it for intel” and orders him to get the Humvee back to Camp Blessing. Wanting to protect his men from a possible attack while waiting, Fry admirably circumvents the command. Later the Army considers making him pay for the vehicle. When a colonel grills Fry, the captain tells his boss that “my men are grateful I was in command that day instead of you.”

And when “the CIA and the Department of Defense were squabbling about who was going to pay for uniforms and equipment for the Afghan Security Force” being recruited and trained by 936, Fry calls a Georgia equipment supplier and orders 130 uniforms himself.

At the end of six months’ deployment and “given all the public recognition, you might have thought that the ‘Camp Blessing model’ would quickly become a new normal. Everyone from DoD on down was saying that our version of counterinsurgency should be replicated. Logically, this insight would have a major impact on policy.

“It didn’t.

“The forces replacing us viewed our population-centric strategy as too ‘passive.’ They preferred a more conventional, enemy-centric approach that would send troops aggressively into the Korengal Valley to stamp out hornets’ nests.”

Why would the Army not follow 936’s path? “I have yet to hear a satisfactory explanation. But I believe it’s important to ask the question—and to question the answer.”

Fry acknowledges that his two years as a Mormon missionary in a different culture, Switzerland, helped him expand his thinking, his world view and his respect for questions.

“Aside from the fact that we were armed, we were more like missionaries than like crusaders. Rather than spreading the Gospel, we were trying to spread a solution to the chaos that Afghans had experienced for the past thirty years.”

J. Ford Huffman has read and reviewed nearly 300 military books, most about the Iraq and Afghanistan War era.