In Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime, Eliot A. Cohen makes a strong and correct case that the dialogue between senior political and military leaders is “unequal.” The basis for this inequality is the unequivocal fact that in democracies, senior political leaders, the president, and, in the U.S., the secretary of defense, have final decision authority. After four case studies—Abraham Lincoln in the Civil War, Georges Clemenceau during World War I, Winston Churchill in World War II and David Ben-Gurion during the Arab-Israeli War—Cohen concludes “that the final authority of the civilian leader was unambiguous and unquestioned—indeed, in all cases stronger at the end of a war than it had been at the beginning.” The question I would like to pose, however, is this: While Cohen’s argument is correct, is it complete—at least with respect to wartime leadership?

Without doubt, the argument in Supreme Command is correct. The U.S. Constitution places the president as the commander in chief, and the law establishes the chain of command that has the defense secretary second behind the president. The Constitution and the law establish who is in control of whom and is the foundation of “civil control of the military.” Further, U.S. military officers are trained and educated from the beginning of their careers as to the importance of proper subordination to civil authority to our democracy. But having final decision authority and using it well are two different things.

Constant Re-Evaluation Required

The president and the defense secretary use final decision authority within a context, understanding that decisions are part of a three-step decision-execution system. The first step, before a decision, involves collecting, analyzing and presenting information as well as options to the secretary and the president. The second is the decision itself, and the last step includes execution then adaptation. War is a dynamic phenomenon, an ever-changing environment. Throughout, therefore, senior political and military leaders must adapt wartime decisions to realities that unfold during war. So whatever decisions are made, they require constant re-evaluation to make sure that a gap does not form between the decision’s desired outcomes and wartime facts as they emerge.

Wartime decisions are not stand-alone events. War is the use of violence to attain political ends. Thus, politics permeates almost every aspect of war, but war also includes nonviolent means to attain political ends. Diplomacy, for example, doesn’t end—or shouldn’t—as war goes on. Economic, industrial, informational, fiscal and domestic political means are also necessary to wage war. Given the totality of means used in a war, therefore, political and military as well as nonmilitary perspectives are essential to ensure the final decision authority receives the information necessary to make the best decision possible. The voices offering these perspectives in the lead-up to a decision as well as in the execution of the decision and adaptation that will always follow—the secretaries of defense, commerce, interior, state, treasury, the director of national intelligence, and others as necessary—are more equal than not. Rare will be the case that any one of these voices is completely right, but each has something important to contribute to discovering an approach “most likely to be right enough.” None of their perspectives is automatically trumped with respect to the others. The final decision authority needs to hear them all, must hear the arguments among them completely, and cannot—or should not—decide until all voices are heard.

In the decision to invade North Africa in World War II, for example, military, industrial capacity and diplomatic factors all played heavily in the final decision, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt considered U.S. domestic political factors as decisive in that case.

The variety of perspectives necessary to inform and provide options to the final decision authority demonstrates the first way in which those who participate in the dialogue are equal. They are functionally equal.

A second way concerns the procedure used in coming to a final decision. Procedures govern the way information is gathered, analyzed and presented to the final decision authority. Most of these procedures are formal “standard operating procedures” more reflective of best practices than of law. Others are informal, using “kitchen cabinets” and other informal advisers.

Using Authority Well

Whatever sort of guarantee the final decision authority may have in making a decision, if “guarantee” can even be used in this context, emerges from a process that ensures the president hears all relevant voices and is presented with all relevant information and options—however difficult such voices, information and options may be. The integrity of the process and the fidelity of the information presented in that process increases the probability that the final decision authority will be used well. A process that is cut short, eliminating or subverting relevant voices and preventing relevant information to rise to the final decision authority’s awareness, decreases the likelihood that the final decision authority will be used well. There is no other “guarantee.”

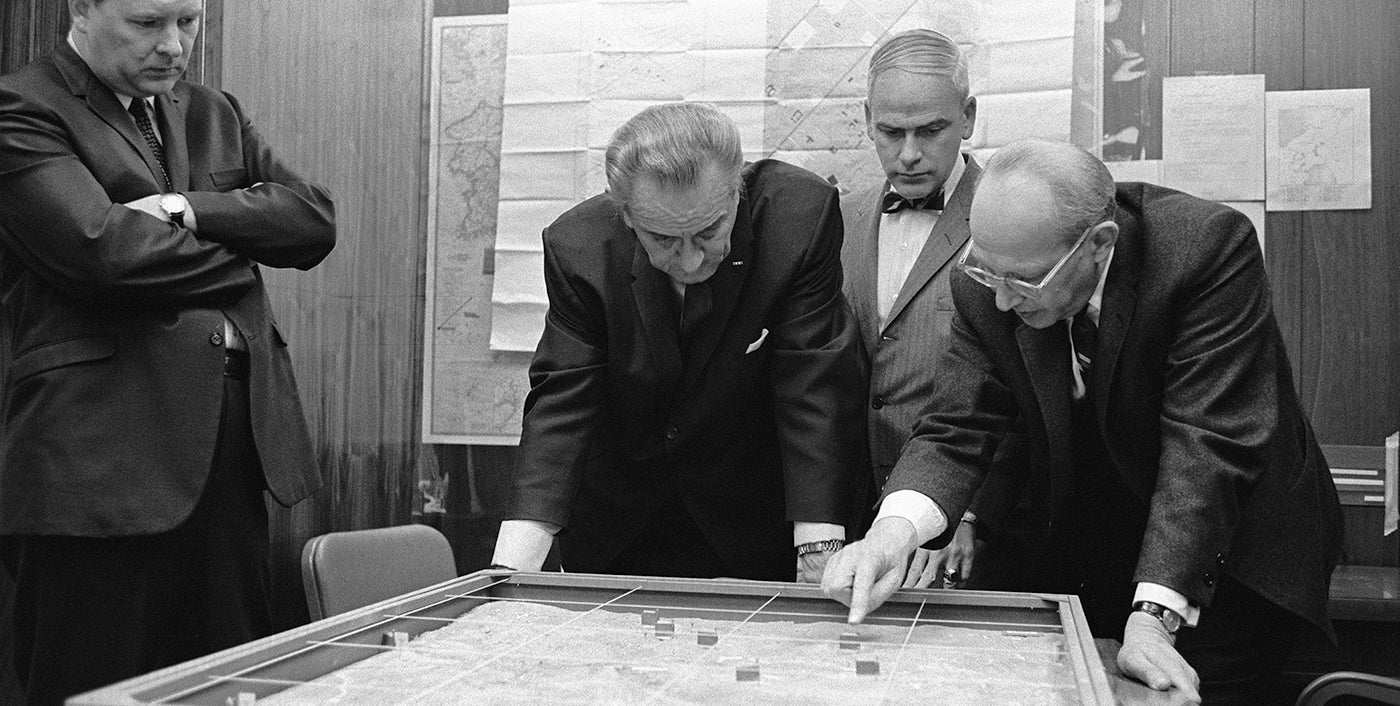

Further, those involved in the lead-up to a decision as well as the execution and adaptation are co-responsible for the integrity of the process and fidelity of the information. No “process police” exist; those involved must police themselves. H.R. McMaster’s Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies that Led to Vietnam provides the perfect example of a process that lacked integrity and information that lacked fidelity: Some of those involved cut out senior military and political leaders whose voice was not welcomed, hid information from one another (as well as from the American public) and prevented options from being fully discussed. The result was final decision authority not well used and lives wasted. As Cohen says in Supreme Command, “After the initial decisions to enter the war, the American civilian leadership held back from the kind of bruising discussions with their military advisors that caused so much grief to Churchill’s subordinates. … During the period of the escalation of the commitment to Vietnam there was no comprehensive politico-military assessment of American Strategy.” Neither did the civilian leadership call for such an assessment, nor did the military leadership insist upon one. Both avoided this critical, war-waging responsibility, a responsibility civil and military leaders shared.

Procedural equality, then, is the second form of equality that applies to those involved in a wartime decision-execution system. Finally, those involved are morally equal.

All the senior political and military leaders involved in wartime decision-making and execution are responsible to the final decision authority and to the American people to do their part in helping make decisions the best possible, given constraints reality imposes upon any particular situation. They are further co-responsible for the execution of and adapting from those decisions.

A Multi-Agency Affair

Executing then adapting from initial wartime decisions is almost always a multi-agency affair. DoD and the uniformed services within it may be the most visible executors, but other departments—like State, Homeland Security, Commerce, Interior and Treasury, as well as various intelligence agencies—have execution responsibility for their parts of a specific decision. Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones’ How the North Won, David Rothkopf’s Running the World: The Inside Story of the National Security Council and the Architects of American Power and Robert M. Gates’ Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War verify that waging war is a multidepartmental activity even when DoD and the military have the greatest roles. After making the final decision, neither the president nor the defense secretary passes around a bowl of water and a towel in a sort of “Pontius Pilate moment” absolving everyone else from their responsibilities. Quite the opposite. All involved feel the weight of their portion of the responsibility—for the decision and the subsequent execution and adaptation.

Functional, procedural and moral equality shed new light on the civil-military dialogue. William Isaacs, in Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together, describes dialogue as trying “to reach new understanding … taking the energy out of our differences and channeling it toward … a totally new basis from which to think and act.” The purpose of the wartime dialogue between senior political and military leaders, then, is not to identify who is in control of whom. Rather, its purpose is best understood as a methodology to discover the most prudent way forward, the best decision possible given the desired aims, exigencies of any situation and the limitations that reality imposes on any given moment. Further, wartime dialogue is practical because the decision that results must be executable by multiple military and civil agencies.

A dialogue is not a debate. The purpose of a debate is to win. In a debate, one debater attempts to create inequality by besting the other. “There is a different sort of spirit” to dialogue, according to David Bohm’s On Dialogue. It’s a spirit of respect, trust and equality. Isaacs continues by describing dialogue as a form of “thinking together [that] implies that you no longer take your own position as final. You relax your grip on certainty and listen to the possibilities that result simply from being in a relationship with others.” The functional, procedural and moral equality of the participants in the wartime civil-military dialogue provides the foundation upon which real dialogue can take place.

Supreme Command acknowledges that “in practice, soldiers and statesmen in war often find themselves in an uneasy, even conflictual collaborative relationship in which the civilian usually (at least in democracies) has the upper hand.” The “uneasy” and “conflictual” aspects of the relationship arise from the complexity of wartime decisions, decisions that are always the result of strongly held and opposing perspectives, conflicting priorities and resource constraints that produce only suboptimal choices. The “collaborative” aspect of the relationship arises from the need of relevant perspectives—civil and military—to be heard, all participants to help assure the integrity of the decision-making process and the fidelity of the information and options presented in that process, and all to assume their responsibilities in the decision, execution and adaptation. The “upper hand” aspect of the relationship arises from final decision authority always residing with civil leadership.

Understood completely, then, the civil-military dialogue has equal and unequal dimensions. The equal aspects of the relationship assure that a dialogue, not a debate, takes place. The equal aspects also allow the necessarily hard give-and-take between senior civil and military leaders to occur. The unequal dimension assures that, in the end, civil authority dominates and military leaders are properly subordinate to that authority.