June 2017 Book Reviews

June 2017 Book Reviews

Former NATO Deputy’s Take on a Shooting War

War With Russia: An Urgent Warning From Senior Military Command. Gen. Sir Richard Shirreff. Quercus. 412 pages. $16.99

By Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano, U.S. Army retired

Retired British Army Gen. Sir Richard Shirreff, former NATO Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe, has written a novel about future conflict: War With Russia: An Urgent Warning From Senior Military Command, which has created a buzz from one end of the trans-Atlantic alliance to the other. The book tells the story of a shooting conflict between Russia and the West in the near future.

Shirreff, whose long military career spans the Cold War and the recent unpleasantness with Russian President Vladimir Putin, tries to address the political and military sides of the current confrontation. Drawing on his four years serving as the No. 2 military officer in NATO, Shirreff’s novel delves into how the alliance makes decisions as well as how its armies fight. War With Russia will invariably draw comparisons to Sir John Hackett’s novels The Third World War and its sequel, The Third World War: The Untold Story. Those books were intended to serve a similar purpose—warning of military threats from the East.

There is more politics than war in War With Russia. The first real shot in anger doesn’t come until about halfway through the book. The 200-page prelude is mostly about anger. There is frustration from military leaders complaining about cuts in conventional forces that created the conditions for Russian aggression. There are also bitter disputes between allied leaders on where to draw red lines and how to convince Moscow to back down. Arguably, this is the best part of the book. Shirreff provides a glimpse of the friction behind the scenes that colors decision-making and command and control of NATO forces.

Once the shooting starts, every aspect of modern war gets at least a cameo appearance. Both sides brandish their nuclear arms. Unfortunately, there is no great insight as to how future wars might be fought—it is mostly just window dressing to move the story along.

Shirreff’s war seems mostly thrown together as a backdrop for railing about NATO’s unpreparedness and lack of resolve to meet Putin’s aggressive and destabilizing polices. There is no real sense of all the complex factors that affect conduct of combat. A real confrontation with Russia over the Baltic region, for example, would have worldwide implications. It is unlikely that players like the Islamic State group, Iran, China and North Korea would just stand around and watch while war rages in the Baltic States. Their response could greatly complicate how the trans-Atlantic alliance takes on Moscow. Not delving into such issues is an opportunity lost.

Shirreff also might have picked the wrong scenario to demonstrate the kind of threat Putin really represents. He wants to re-establish a hard belt of security around the Russian state with a sphere of influence that includes dominating the politics, economies and militaries of the border lands that matter to him, but Putin is eager not to repeat the mistakes of the former Soviet Union.

Establishing and maintaining a solid sphere will always be threatened if U.S. forces remain in Europe. Removing them requires bringing an end to NATO. Getting rid of the alliance demands showing it is no longer relevant. Ending the relevance of NATO means showing that Article 5, the treaty commitment to mutual defense, is a hollow promise. What Putin is looking for is not a war of conquest in Central Europe, but an opportunity to test Article 5 in a way that won’t risk World War III. Putin is posturing so he is ready to press NATO on its solidarity. If NATO blinks, he wins. If it doesn’t, he will back off and look for another opportunity.

The U.S. and NATO do need to ramp up their game—making clear there is political resolve and the capacity to defend every member of the alliance. That means, among other initiatives, more member-state defense spending, more U.S. troops permanently stationed in Europe, more air power over Central European skies, and more air and missile defenses. In the end, that is the underlying message of War With Russia. Critics can dispute the merits of the novel, but NATO leaders should pay attention to the message. To ignore the warning—that it is past time to ignore warnings about Putin’s Russia—is to risk the stability of a part of the world where the U.S. should not be willing to risk peace, freedom and security.

Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano, USA Ret., is a Heritage Foundation vice president in charge of the think tank’s policy research in defense and foreign affairs.

* * *

An Inside View of Nation-Building in Vietnam

Jack of All Trades: An American Advisor’s War in Vietnam, 1969–70. Ronald L. Beckett. Stackpole Books. 239 pages. $19.95

By Col. Paul T. DeVries, U.S. Army retired

Most of the books about the Vietnam War have dealt with moments of sorrow, camaraderie, exhilaration, fear, violence, compassion, sacrifice and brutality, and most have focused on the combat experience. Jack of All Trades is different. It is a book about the advisory mission, an experience unique unto itself. In it you will find no recounting of battles or firefights and no in-depth analysis of strategy or tactics. There are no political messages and few moral judgments. Rather, this is a collection of true and often humorous anecdotes arising from one advisory team’s experience. More specifically, it is the story of a seven-man American District Advisory team in the Dinh Quan District, Long Khanh Province, III Corps Tactical Zone, Republic of Vietnam in 1969 and 1970.

An advisory effort was conducted by the U.S. from the inception of Military Assistance and Advisory Group-Vietnam during the 1950s following the departure of the French, and into the early 1960s when President John F. Kennedy expanded it. This advisory effort was almost exclusively centered on South Vietnamese Army combat units. In 1964, with the establishment of Military Assistance Command Vietnam, American strategists began to realize that Mao Zedong’s dictum that the people must support an insurgency for it to be effective was far more than the ravings of a Chinese despot. And so it was that American attention turned to strengthening, albeit slowly, the regional and administrative organizations of South Vietnam. Whether it realized it or not, the U.S. had embarked on a massive campaign of nation-building. It was into this situation that in 1969 Maj. Ronald L. Beckett returned to Vietnam, assigned as the district senior adviser of the Dinh Quan District.

Beckett had deployed in 1965 with the Army’s 1st Infantry Division, “The Big Red One,” as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s response to the North Vietnamese incursion. He had seen combat as a company commander and understood the U.S. conventional war tactics of “search and destroy.” But now he was participating in a different kind of war, the war to win the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people. In Jack of All Trades, he describes the day-to-day lives of American advisers at the Vietnamese district level in a way few Americans, including those who served in U.S. units, understood.

Jack of All Trades is a book about events and moments worth preserving, a book about the American war in Vietnam. It is not, however, a book about war in the traditional sense. Neither is it a book about heroism, though it has heroes, nor is it a book of protest, though it is sometimes critical. This is a book about people, places and events that marked the author’s tour of duty in Vietnam. It is a book bound loosely by the thread of human experiences—a book that will move the serious reader to laughter and resurrect emotions about the “other war” in Vietnam.

This book is a must-read for those who served as advisers at the district and province levels and for those interested in Vietnam War history. It also provides an insight into the U.S.’s attempts to build a nation while fighting a war.

Col. Paul T. DeVries, USA Ret., is a combat infantryman with 30 years of service. He served in Vietnam as an adviser at the province level, as S3 and executive officer in the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division, and as an adviser to the Vietnamese Airborne Division.

* * *

Suffering on Edges of Civil War

Extreme Civil War: Guerilla Warfare, Environment, and Race on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier. Matthew M. Stith. Louisiana State Press. 218 pages. $42.50

By Lt. Col. Robert Bateman, U.S. Army retired

Civil wars are often the most brutal. These conflicts, when fought by, among and through civilians—often neighbors—can transcend mere brutality and descend into true barbarity, which was the case in the Trans-Mississippi West during the American Civil War. Now, Matthew M. Stith shines the light of historical research on the topic in his book Extreme Civil War. This is a solid work of academic history, decently written and mercilessly even-handed. No side in this comes out looking or smelling clean. But that is what good history is about: telling the story, warts and all.

Stith, an assistant professor of history at the University of Texas at Tyler, understands that to cover this topic for the entire Trans-Mississippi region would be nearly prohibitive, and so the book is deliberately limited in its geographic scope to make the telling digestible, if not palatable. The focus is upon a roughly 100-by-100-mile area around where Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas and what was then Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) come together. By narrowing in on this geographic locus, Stith gains the space he needs to bring depth to a story which is as thorough as it is depressing.

He makes it clear that as bad as things were when the large regular armies of the Civil War clashed, life for the inhabitants of this blighted land were orders of magnitude worse. Here, there were few uniformed armies marching under battle flags, but instead, guerillas, bushwhackers, thieves, murderers, looters, and not a few who met all those descriptions. There were few heroic stands by embattled divisions struggling to hold the corps lines, but thousands of what Stith calls microbattles, often waged on front porches and in barnyards over more than politics; over the very stuff of life on the frontier—corn, hogs and cows.

Some of this ground has been covered before. Mark Grimsley of Ohio State University broke ground 20 years ago with his Lincoln Prize-winning book The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865. Later, Robert Mackey showed us aspects of the reverse of the coin, at the tactical and operational level, with his book The UNcivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861–1865. Now Stith, with Extreme Civil War, provides depth and specificity to this developing area of study. Speaking of his chosen area Stith writes, “War there was a messy, confusing, and altogether brutal affair, blurring the lines of what had been deemed honorable or civilized warfare—the stuff for regular armies fighting regular battles in regular campaigns. The intense racial and political hatred that helped fuel the conflict became its very centerpiece in the Western margins.”

Indeed, one can hardly imagine a more charged cauldron than what Stith describes. There were no clear boundaries, physical, political or moral. There were pro- and anti-Confederate Indians of two tribes, whites divided politically and socially down to the homestead level, freed and enslaved blacks, and added to this mix were the “regular” forces of the U.S. and the Confederacy. Pile upon all of those factors the localized and intensely personal nature of some of the fighting, neighbor against neighbor, and one begins to see how things spiraled out of control. If you have seen the recent film Free State of Jones (set in eastern Mississippi), magnify all those factors by 10 and you start to get the picture.

This is not a book for the casual reader seeking a survey of the war or the great leaders of the period. It is a book about brutality and the emphasis is upon the victims, invariably civilians who found themselves in the path of war regardless of their sympathies. Here there are no real heroes, and if one has served in Iraq, Afghanistan or Vietnam, many of the issues and problems found in this history will echo resoundingly. Well-documented and generally well-written, Extreme Civil War is a book with utility for professionals and those seeking a truly in-depth understanding about the totality of America’s most total of wars.

Lt. Col. Robert Bateman, USA Ret., served for 25 years as an Army officer. He taught military history at the U.S. Military Academy; George Mason University, Va.; and Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books and is currently writing one about the interwar period.

* * *

Provocative Study Shatters Myths of American Frontier

The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West. Peter Cozzens. Alfred A. Knopf. 575 pages. $35

By Col. Cole C. Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

No period in American history is more steeped in myth and legend than the era of the Indian Wars in the American West. In The Earth Is Weeping, acclaimed author Peter Cozzens has produced the most comprehensive one-volume narrative of the clash of civilizations that dominated the American frontier in the last half of the 19th century.

Cozzens is the author or editor of 16 books on the American Civil War and the Indian Wars of the American West, including the five-volume Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars that the History Book Club labels “the definitive resource” on that military struggle. In addition to his works on the Indian Wars, Cozzens, a retired Foreign Service officer with the State Department, has written a Civil War trilogy on the Battles of Stones River (No Better Place to Die), Chickamauga (This Terrible Sound), and Chattanooga (The Shipwreck of Their Hopes).

Based on a plethora of Native American primary sources, Cozzens hopes to “bring historical balance to the story of the Indian Wars.” He succeeds admirably and shatters two prevailing myths: that the Regular Army was the implacable foe of the Indians, and that the Indians presented united resistance to white encroachment. In contrast to Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, whose special purpose was the presentation of “the conquest of the American West as the victims experienced it,” Cozzens states emphatically that Brown’s approach is “one-sided,” making it virtually “impossible to judge honestly the true injustice done the Indians, or the Army’s real role in those tragic times.”

In reality, “No tribe famous for fighting the U.S. government was ever united for war or peace.” The Native American tribes were riven by “intense factionalism,” and each tribe contended with “war and peace factions that struggled for dominance.” Intertribal conflict was the rule, not the exception, of life on the plains. Furthermore, no sense of “Indianness” appeared until it was too late. As Cozzens notes, “The wars between Indians and the government for the Northern plains, the seat of the bloodiest and longest struggles, represented a displacement of one immigrant people by another, rather than the systematic destruction of a deeply rooted way of life.”

Cozzens’s treatment of Custer’s Last Stand is exceptional, as is his retelling of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perces’ abortive trek to reach Canada in 1877. In a sense, the Native American victory at Little Bighorn, Mont., was the Lakota-Cheyennes’ “last stand” as well. After Capt. George Armstrong Custer’s defeat, the U.S. government was united in a single objective: to crush Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and lock up the Lakotas and the Cheyennes on reservations once and for all.

President Ulysses S. Grant secured congressional funding to raise additional forces and Gen. Philip Sheridan embarked on a winter campaign against the non-treaty Lakota and Cheyenne. By September 1877, Crazy Horse was dead and Sitting Bull had migrated to “Grandmother’s Land,” Canada, to escape “the Great Father’s fury.”

A similar tragedy played out within the habitat of the Nez Perce, led by the dynamic Chief Joseph. Like Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph attempted to lead his tribe on a 1,700-mile trek to “Mother” Canada. Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, “the Christian general,” took up the chase, urged on by General-in-Chief William T. Sherman’s edict to make the Nez Perce “answer for the murders they committed and punished as a tribe for going to war without any just cause or provocation.” The Nez Perce hegira ended in October when Chief Joseph proclaimed to his chiefs: “I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

By 1890, the American frontier was finally closed, and the military conquest of the Great Plains was complete. Yet the U.S. 7th Cavalry still had a final card to play. On Dec. 29, 1890, the soldiers of “Custer’s own” surrounded 120 men of fighting age and 250 women, children, and elderly Miniconjous and Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux. Few men on either side had ever seen a fight, leading to indiscriminate shots being fired as the soldiers attempted to disarm the Indian band. Within a half-hour, the Lakota camp ceased to exist. When the surviving Lakota chiefs capitulated on Jan. 15, 1891, at Pine Ridge Agency in what is now South Dakota, the Indian Wars for the American West were finally over.

Cozzens has produced a tour de force in the literature of the American West. Highly readable and equally provocative, The Earth Is Weeping is narrative history at its best. By challenging conventional interpretations of history, Cozzens has added an exciting chapter in our understanding of the wresting of the American West from the Native American tribes.

Col. Cole C. Kingseed, USA Ret., a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate from Ohio State University.

.* * *

Battle Defined Officer’s View of Leadership

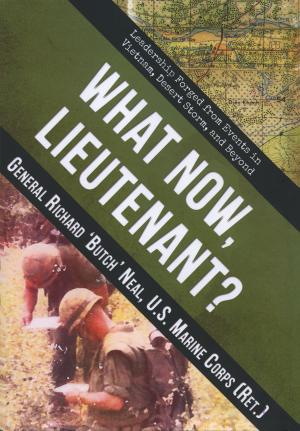

What Now, Lieutenant?: Leadership Forged from Events in Vietnam, Desert Storm, and Beyond. Gen. Richard ‘Butch’ Neal, USMC Ret. Fortis. 255 pages. $26.95

By Rick Maze

Editor-in-Chief

It is rare for ARMY magazine to review a book written by a Marine, but this collection of memories by a retired assistant commandant is filled with lessons about leadership in combat from someone who sees his life defined by a six-hour battle fought in Vietnam in March 1967.

Gen. Richard Neal, who spent 35 years in the Marine Corps before his 1998 retirement, was a history major at Northeastern University in 1962. He picked the Marine Corps over the Army for what he recalls was the purely practical reason of being a commuter student with a full-time job who was trying to balance his life. The Marine Platoon Leaders Class was easier to fit into his schedule than Army ROTC.

His first of two tours in Vietnam began in 1966. He spent most of his first six months as an artillery forward observer responsible for a small team. But that changed when his company was assigned to Operation Prairie III in Quang Tri Province with a mission of finding and ambushing enemy forces. They’d been ordered to break into three platoons to launch attacks, with the young platoon leaders torn between obeying orders or sticking together in what they thought was a safer option.

The sense of foreboding proved right. In the span of about 45 minutes, and under a heavy rain of mortar shells, Neal’s role shifted from forward observer to medic to a combination radio operator, forward air controller and company commander as 15 Marines were killed and 47 Marines and Navy corpsmen were wounded within a few minutes.

“On that day, I became a great believer in eyeball-level leadership,” he writes. “I had to keep in mind I was talking to human beings—tough young men—who had just gone through a life-changing experience, one that would be with them for the rest of their lives.”

Eye-level leadership, looking your troops in the eye and listening to what they say was something Neal says he applied throughout his career, and is also something that would serve any young military leader.