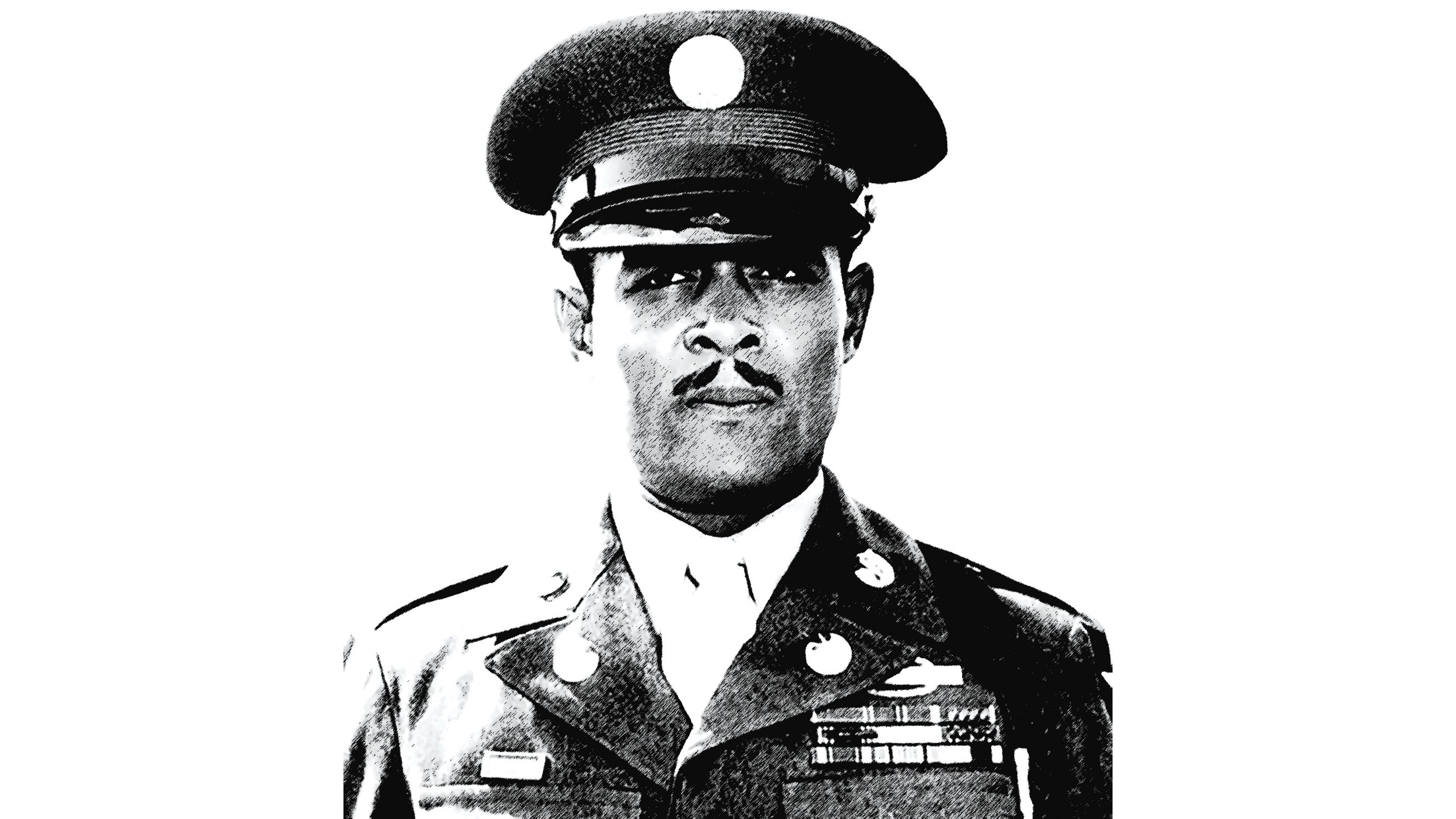

Like Gen. George Patton Jr., Edward Allen Carter Jr. believed he was a reincarnated warrior. Carter fought in three wars from 1932 to 1945 with three different armies. He was prevented from fighting in a fourth, the Korean War. And as a mixed-race man in a segregated U.S. Army, he battled racism throughout his career.

It was only well after his death that Carter’s family received the Medal of Honor on his behalf.

Carter was born on May 26, 1916, in Los Angeles. His father was of African descent and his mother of Indian descent. In 1922, Carter’s father took a missionary job in Calcutta, India, now known as Kolkata.

As a youth, Carter told his mother he had dreams of having been a warrior in previous lives. Shortly thereafter, his mother disappeared to go live with a more prosperous spouse. Carter never understood her departure, blaming his father for why his mother abandoned him.

With their family life disintegrating, the senior Carter got his Los Angeles church to fund his return to California. By this time, the younger Carter would have been 14.

A New Life

The ship the Carters departed on had a layover in Shanghai. Carter Sr. was desperate for funds, and he took a new, more prosperous missionary job in that city. The Shanghai International Settlement became their new neighborhood.

By age 15, Carter Jr. so disdained his father over his mother’s departure that theirs became a vengeful relationship. Carter was sent off to a popular military academy associated with the international neighborhood. The student body consisted of numerous German students, and Carter mastered the German language, which would be beneficial in an upcoming war.

By then he spoke English, Hindi and German, and he was mastering Mandarin. His classes involved the expected subjects of military history, discipline, tactics, drill, weapon familiarity, etc. In countries such as India and China at that time, American racial issues were as foreign as was having an American in their midst. Then came Jan. 28, 1932.

Itching for a Fight

On that date, Japan invaded Shanghai. Fifteen-year-old Carter ran away to fight the Japanese. Local Chinese resistance leaders were so impressed with Carter’s language skills and military knowledge that they made him a lieutenant. It is uncertain whether Carter’s involvement included combat. If nothing else, his efforts likely would have focused on logistical support for actions on the streets of Shanghai.

When Carter’s father heard of this, he insisted Chinese authorities return Carter home, since he was a neutral citizen and a minor. That only infuriated Carter more, and he ran away a second time shortly thereafter.

This second adventure found Carter aboard a merchant ship bound for Manila in the Philippines, where he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army. Lacking age documentation, he was denied entry. He went back to sea and eventually landed in the United States. From there, he became a volunteer infantryman in the Spanish Civil War of July 17, 1936–March 28, 1939.

That civil war has been seen as a precursor to World War II, which followed six months later. In the final 22 months of the civil war, 2,800 Americans arrived in Spain in small groups or individually, as international circumstances allowed, to help fight fascism. They were exposed to tactics and the machinery of war that became common in World War II.

In the midst of all that, Carter found his way into the Spanish Civil War as a member of the Black-led Abraham Lincoln Brigade. His arrival and departure remain mysterious, but he had found a second army to join. He is credited with being at the Dec. 14, 1937–Feb. 22, 1938, Battle of Teruel, which devolved into house-to-house fighting. Carter was taken prisoner but managed to escape, probably avoiding execution. With fascism winning out in Spain, Carter made it back to America.

Finally, a U.S. Soldier

On Sept. 26, 1941, 25-year-old Carter joined the segregated U.S. Army. Through basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, he rapidly adapted to military life, mastering any weapon system handed to him and outlasting other recruits 10 years younger in field exercises. Younger recruits looked to him for guidance in mastering military life.

From Texas, Carter moved on to the 3535th Quartermaster Truck Company at Fort Benning, Georgia. He quickly advanced to the rank of sergeant, doing double duty as cook, then supervisor, of 64 Blacks operating an all-white officers’ club.

By mid-1944, Carter’s company was in France doing nothing more than labor detail when not driving trucks. Almost every day for months, Carter requested transfer to a front-line combat assignment. Each request was met with a “No.”

By December 1944, the Army came to a sad conclusion. It was short 23,000 qualified riflemen for direct battle. Then came the Battle of the Bulge of Dec. 16, 1944–Jan. 25, 1945, which worsened those numbers.

To offset that, the Army made changes many career soldiers found hard to accept. Black soldiers and soldiers considered Black, like Carter, would be sought to volunteer to upgrade their basic combat skills and be rushed directly into battle.

Staff Sgt. Carter jumped at the invitation. He forfeited his stripes to become a private first class because the rule was that no Black soldier, regardless of seniority, could order any white soldier. Rank meant little to Carter if relinquishing it got him into fighting fascism a second time.

Another rule was that once the manpower shortage evened out and the winds of war turned more favorably to the U.S. Army, the Black soldiers would return to their original duty assignments. For the time being, Carter was attached to the 56th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division.

Heroic Actions

On March 23, 1945, Carter rode atop an M4 Sherman tank in a column approaching Speyer, Germany. This town sat upon the west bank of the Rhine River. Once across the river, the Allies entered Germany’s heartland.

According to his Medal of Honor citation, near Speyer, Carter’s tank took bazooka and small-arms fire. Carter went off in search of the origin of the fire with three other Black GIs following.

As they crossed an open field, a member of the squad was killed, and Carter insisted that the other two members of the squad return to safety and cover him with rifle fire while he proceeded, alone, to carry out the mission. He crawled within 30 yards of his objective, killing six enemy soldiers and capturing two.

Carter was wounded in his left arm, left leg and left hand. Since the climate of racism and segregation that prevailed in the Army at the time prevented Black soldiers from receiving the Medal of Honor, he received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Seeking a Career

Following that war, his third, Carter returned to Los Angeles, got married and had two children. Within a year, he was back in an Army uniform with the segregated California Army National Guard. He transferred into the Regular Army, winding up at Fort Lewis, Washington, doing NCO military police duty. For some time, he was the personal guard and escort to base commander Gen. Paul Kendall.

Midway through this enlistment, Carter decided to go career Army and submitted a reenlistment request. This was rejected. The FBI had caught onto Carter’s Spanish Civil War involvement and deemed him a national security risk; the Army followed suit and discharged him, honorably, as of October 1949.

Carter went through his immediate chain of command to try to resolve the problem. He took it upon himself to travel to Washington, D.C., to try to haggle with the Department of the Army. He ended up sitting in a chair in a hallway and was never seen.

Stuck with a discharge he never envisioned, he mailed his Distinguished Service Cross back to the Army.

Carter died on Jan. 30, 1963, in Los Angeles. On Jan. 13, 1997, President Bill Clinton presented Carter’s family with his overdue Medal of Honor.

Food for thought: Carter could have served in another war, in Korea. How vital would his experience have been there?

Carter’s final resting place is at Arlington National Cemetery.

* * *

Stephen Lutz is a military researcher and writer. He served five years in the Army Medical Corps as a medical specialist, spending 22 months in Thailand, Vietnam and Korea.