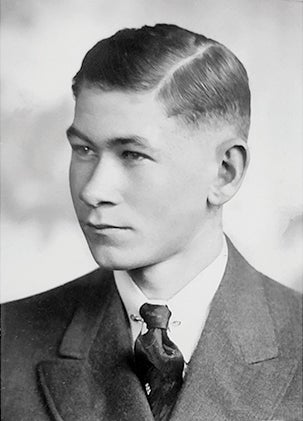

Sgt. 1st Class Alan Boyer was 22 when he went missing in Savannakhet Province, Laos. He was on a classified special operations mission as part of an 11-man team assigned to the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group.

He and his team of U.S. and Vietnamese soldiers requested aerial extraction when they came under enemy fire. The terrain was too rugged for the responding U.S. helicopter to land, so a ladder was lowered to the men on the ground.

Several team members made it into the aircraft before the ladder broke, and the helicopter was forced to leave under heavy fire. Boyer, a Vietnamese soldier and two other U.S. soldiers—Sgt. 1st Class George Brown and Sgt. Charles Huston—were left behind, never to be seen alive again.

The date was March 28, 1968. Almost 48 years to the day, on March 7, 2016, Boyer’s sister received a call from the Army saying a bone fragment had been found that matched her brother’s DNA.

Boyer’s remains, and those of thousands of U.S. service members, have been recovered through the work of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the organization that, first formed as Joint Task Force-Full Accounting, has been recovering and repatriating the remains of U.S. service members since 1985.

Difficult Mission

The painstaking mission began 10 years after the end of the Vietnam War, but more conflicts were added over time. As of October, there were still close to 82,000 people missing from World War II and Korea through Operation Iraqi Freedom. Of those, more than 42,000 are soldiers who were with the Army or the U.S. Army Air Corps when they disappeared. Most of the losses are in the Indo-Pacific region.

More than 72,000 Americans remain unaccounted for from World War II, more than 1,500 are unaccounted for in Vietnam, and three men working as DoD contractors who disappeared between 2003–07 in Iraq are on a list of missing Americans in the Middle East.

It’s a tough mission with international challenges for teams of historians, researchers, scientists and anthropologists who are deployed and conducting investigations and fieldwork in 19 countries.

The discovery and repatriation of remains don’t always lead to identification, even though the agency has a database filled with DNA samples from relatives. But it can take decades to find a missing loved one and, as the years go by, older generations pass, and remaining relatives may close the chapter on a missing service member they never knew. Some relatives distrust the government and are reluctant to donate a DNA sample, and at times, there can be confusion in family history with adoptions and extended families.

Gaining Momentum

But the agency’s work has recently gained more traction and momentum, thanks to continuing advancements in technology and a wider network of nations willing to help coordinate the identification of sites and recovery of remains.

The agency’s reliance on the use of DNA to identify people has been “one of the most efficacious lines of evidence” over the course of the mission, said Kelly McKeague, the agency’s director. “We may find only a single tooth,” he said, but that’s enough.

While DNA from a tooth or teeth matched against a soldier’s service dental records is “almost the holy grail” for identification through DNA, McKeague said, new advancements in laboratory technology are allowing scientists to identify badly damaged remains in cases that used to be declared unresolved.

“What’s changed with DNA … that’s become almost indispensable, is that DNA can be extracted from remains that have been chemically treated,” McKeague said, explaining that many deceased U.S. service members who were unable to be identified in the 1940s and 1950s from World War II and Korea were buried as “unknowns.”

“But before they were buried, they were treated with formaldehyde powder, and that alone eats away at the DNA. So, our scientists at the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory have perfected techniques, in fact, patented techniques, that allow the extraction of DNA even from chemically treated remains,” McKeague said.

This technology was critical to identifying remains received by the U.S. on Aug. 1, 2018, at the agency’s laboratory at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, following the June summit between then-President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un.

Contained in 55 flag-draped boxes were 250 different DNA sequences. Through the analysis, the remains of 77 U.S. service members and 70 South Korean soldiers were identified. Some 7,500 U.S. soldiers are listed as missing from the Korean War, and the bulk of those are believed to be in North Korea.

Unidentified remains are kept at one of the agency’s two laboratories—the one in Hawaii and a second lab at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska. A number of those remains from the field, turned over by a partner nation or disinterred from a U.S.-controlled cemetery, are under analysis at any given time, McKeague said.

“They’re in various stages of analysis, but for those where we’ve reached a dead end in terms of having no idea who these remains belong to, we will keep them in our laboratory pending new information, new evidence that may come forward at some future date,” McKeague said.

Leveraging Technology

Technology continues to expand the agency’s capabilities every year, McKeague said, not only in the laboratory but also in the field.

By leveraging technology, and the resources and capabilities of other U.S. organizations with historical and archival research skills, forensic anthropology expertise and assets that help with field operations, the agency has expanded its ability to further scientific innovation.

The agency works closely with the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System and DNA Identification Laboratory, as well as the U.S. Army Casualty Office at Fort Knox, Kentucky, which helps with genealogy and notifies families when identifications are made.

Those capabilities are further enhanced through partnerships with 46 countries where it is believed American remains will be found. With the help of host nations’ militaries, museums, government archives and oral histories, the agency has expanded its focus around the globe, especially since 2010 when Congress added World War II as part of its mission, McKeague said.

He offered as an example the recent discovery off the coast of Denmark of a U.S. Army Air Forces B-24 bomber. The Royal Danish Navy found the wreckage, then helped set in motion the recovery by providing ships, explosive ordnance disposal technicians and divers.

“They found it, surveyed it, found what we believe to be useful evidence, and we will then dive it next year for the underwater recovery,” McKeague said.

Western countries like the U.K., Australia, France and Germany, he said, “tend to take a more reactive approach” to helping with the mission, for example, reaching out “should someone come across the remains of what they believe to be their own.”

In Australia and the Netherlands, he said, the recovery mission is carried out by small army units that are “talented in their own right,” but not proactively searching like the U.S. and South Korea.

“The only country that rivals the United States in terms of the proactive position, in terms of the capabilities and capacity, is South Korea. We helped stand up their comparable agency back in 2001, and they have just gone, literally, leaning into this,” McKeague said. “They are by far closest to us in terms of passion, commitment, talent and capabilities.”

Sacred Obligation

Describing the agency’s mission as “very linear,” McKeague said the discovery of potential sites “happens every day,” and each begins with historical research, combing through archives in the U.S., in Army units, in European churches and anywhere in the world agency officials can piece together information about the missing.

Using these bits, a case is developed that can progress to a field investigation where a small team works to gather additional details in the area. If they manage to pinpoint a more concentrated area, an excavation team is dispatched, as happened with the discovery of the B-24 in a “linear process that likely began five years ago,” McKeague said.

Working with a private partner that performed a sonar survey of the area, the aircraft wreckage was located, sparking a field investigation and next year’s planned site dive.

With close to 82,000 people still unaccounted for, of which 38,000 are estimated to be “recoverable,” McKeague said, “I don’t think we’ll ever reach a point where we will dust off our hands and say we’ve done everything humanly possible, because we haven’t.”

Fully preserved human skeletons are still being found on the beaches of Tarawa, Kiribati, occupied by Japan during World War II; and in Europe, identifiable remains are being found in soil and underwater “in good condition and yielding DNA,” he said.

“Until we reach a point where that’s no longer feasible, I don’t see us decreasing our commitment or, more importantly, walking away from our sacred obligation … on behalf of those that paid the ultimate sacrifice and their families,” McKeague said.

* * *

Never Forgotten

Sgt. John Hurlburt, 26, of Madison, Connecticut, was accounted for on Aug. 19, 2020. He was killed July 7, 1944, on the island of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands when his unit, the 105th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division, was attacked by Japanese forces. Hurlburt’s dog tags were found in March 1948 in the 27th Infantry Division’s cemetery, but the remains were determined not to be his. On Dec. 6, 2018, after more research, remains believed to be Hurlburt’s and those of eight of his fellow soldiers were disinterred from the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.

Never Forgotten

Pvt. Lyle Reab, 22, of Phillips, Nebraska, was accounted for on Feb. 24. Assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 112th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, his body was not recovered following a Nov. 9, 1944, firefight with German forces at Vossenack in the Hurtgen Forest. Several remains were found in the forest following the war, but Reab remained unaccounted for. He was declared nonrecoverable in December 1950, but researchers determined that remains found in a foxhole near the German town in March 1948 and buried as an unknown soldier in the Ardennes American Cemetery in 1949 could belong to him. The remains were disinterred in June 2018 for identification.

Never Forgotten

Cpl. Charles Hiltibran, 19, of Cable, Ohio, was accounted for on April 20, 2020. He was a member of the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. He was reported missing on Dec. 2, 1950, when his unit was attacked by the enemy near the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. Following his death in the battle, his remains could not be recovered. Hiltibran’s remains were returned to the U.S. by the North Koreans on Aug. 1, 2018.

Never Forgotten

Maj. Donald Carr, 32, of San Antonio, was accounted for on Aug. 19, 2015. He was assigned to Mobile Launch Team 3, 5th Special Forces Group, as an observer in an OV-10A aircraft supporting an eight-man Special Forces reconnaissance team in South Vietnam on July 6, 1971, when his aircraft encountered bad weather. An explosion to the northeast was heard by the ground team, which assumed it was Carr’s aircraft, but the crash site was never found, and Carr was declared missing in action. His remains were returned to the U.S. in April 2014.

Never Forgotten

Lt. Col. Robert Nopp, 31, of Salem, Oregon, was accounted for on Feb. 1, 2018. Assigned to the 131st Aviation Company, on July 13, 1966, he was flying an OV-1C aircraft on a night surveillance mission from Phu Bai Airfield over Attapeu Province, Laos. Visibility was poor due to heavy thunderstorms. Radar and radio contact were lost with the aircraft, which was not uncommon in the mountainous terrain in that part of Laos. The aircraft failed to return on schedule, and no crash site was found during a search. Also lost in the crash was Staff Sgt. Marshall Kipina, 21, of Calumet, Michigan (below). The two men were identified together.