The Story of Operation Inherent Resolve

Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump. Michael Gordon. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 496 pages. $30

By Brig. Gen. John Brown, U.S. Army retired

Michael Gordon is an accomplished chronicler of recent American wars. In Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump, he delivers a superb account of Operation Inherent Resolve, the American portion of the 2014–19 campaign to dismantle the Islamic State group’s “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria.

With the late Marine Lt. Gen. Bernard Trainor, Gordon has already authored such fine histories of U.S. operations in the Middle East as The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Iraq, from George W. Bush to Barack Obama; Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq; and The Generals’ War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf.

Degrade and Destroy carries the story forward, transitioning from those earlier wars to operations of the more recent past.

Gordon develops his narrative chronologically in 22 chapters. Most chapters interweave events at the strategic, operational and tactical levels. Thus, debates at the White House or among grand strategic players juxtapose with actions and consequences on the ground.

The operational level—the province of generals, colonels and their counterparts—is particularly well developed.

First, Gordon catalogs Iraq’s deterioration after the U.S. departure in 2011 and the shocking sequence of Islamic State group victories that overran Iraq and Syria.

Then, the improbable allies opposed to the Islamic State group figured out how to cooperate and arrest its advance. These allies eventually battled their way back to recapture Mosul and, ultimately, extinguish the Islamic State’s caliphate as a geographical entity.

Gordon’s introduction is brief but adequate; his epilogue is comprehensive, insightful and in itself worth the price of the book.

Gordon deepens our understanding of hybrid warfare, the mixing of multiple levels of the combat spectrum at the same time, in the 21st century. To this he adds an appreciation of “marbled” warfare, where partners in a conflict each have different agendas and may not even like each other. The U.S. envisioned fighting done by a diverse mix of local allies with narrowly circumscribed American military support through an agreed diplomatic and legal framework.

This “by-with-through” strategy minimized American exposure but also reduced U.S. leverage in decisions made on the ground. Time and again, U.S. advisers found their recommendations downplayed or ignored altogether. Negotiated retreats, for example, recurrently enabled Islamic State group forces to fight another day.

The minimalism of by-with-through, accompanied by crippling force ceilings and bureaucratic constraints, emerged from American disenchantment with what critics called “forever wars.” Polling and political considerations trumped clear-eyed military assessments to match means with stated objectives.

Gordon dissects the strategic decision-making of both the Obama and Trump administrations. He finds one less shambolic than the other, but both experienced an exhaustion of strategic patience. American soldiers had to do more with less. Inherent Resolve nevertheless came out a victory, warts and all.

Gordon justifiably worries that lessons to be learned from Inherent Resolve will remain unaddressed. The strategic pivot to Russia and China, even more dramatic now than when he wrote, eclipses interest in the global war on terror. Yet the threat remains, and the U.S. can’t ignore it just because we’re tired of it.

Degrade and Destroy is must reading for all who want to stay current with military history, and for all who are committed to seeing the global war on terror through to a successful conclusion.

The book is amply supported by maps, endnotes, an index and a six-page listing of dramatis personae.

Brig. Gen. John Brown, U.S. Army retired, served 33 years in the Army, with his last assignment as chief of military history at the U.S. Army Center of Military History. The author of Kevlar Legions: The Transformation of the United States Army, 1989–2005, he has a doctorate in history from Indiana University.

* * *

Important Case Studies in Lousy Leadership

The Worst Military Leaders in History. Edited by John Jennings and Chuck Steele. Reaktion Books. 336 pages. $24

By Michael Robbins, U.S. Army retired

The title of this anthology, The Worst Military Leaders in History, reads like the subject of an after-hours gab session for a band of military historians. Indeed, the editors of this book, John Jennings and Chuck Steele, are history professors at the U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado, and they concede that the book draws upon informal discussions among the faculty.

Focusing on the worst, the failures and losers, is admittedly an unconventional approach to the subject, but that doesn’t mean it’s not useful: It examines the behavior of leaders who failed badly, even catastrophically, as a result of their own errors and character flaws, their lack of strategic vision or their tactical ineptitude.

The usual measure of a successful leader is winning: a victory on the battlefield or winning a campaign or a war. But combat is often complicated by factors like weather, terrain, weaponry, logistics, troop morale and many other variables outside commanders’ control. And, as always, enemy forces have a vote in the outcome.

The authors of these 15 examples concentrate on the character of the commanders. The editors have grouped the types of characters into five categories: “Criminals,” “Frauds,” “The Clueless,” “Politicians” and “Bunglers.” Many of these commanders qualify for several categories.

These essays are at once cautionary tales and illuminating profiles. It seems likely that as many worthwhile lessons can be learned from these failures as from history’s successes.

Prominent among the three “Criminals” stands Nathan Bedford Forrest, a wealthy slave trader, Confederate cavalry leader and a postwar chief of the Ku Klux Klan. Revered by some for his victories as a small-scale raider, Forrest ignored the distinction between military combat and plain murder.

He was commander of the Confederate cavalry that assaulted Fort Pillow, Tennessee, in 1864. That attack ended with Forrest’s cavalry massacring hundreds of African American soldiers after they surrendered.

Another military criminal commander, Col. John Chivington, was directly responsible for the deliberate killing of hundreds of noncombatant Native Americans, mostly women and children, encamped at Sand Creek, Colorado, in November 1864. Chivington had instructed his soldiers to kill every person there––an indefensible atrocity that resonates to this day.

The three identified as “Clueless” presided over unusually high-casualty operations. They are George Custer, a cavalry commander in the Civil War and postwar campaigns against Native Americans; Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, in charge of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s army during World War I; and Lewis Brereton, a U.S. Army major general at the onset of World War II.

Custer famously died as a direct result of his Little Bighorn hubris and tactical blunders. Conrad, as he was known, almost single-handedly destroyed his own army—with over 2 million casualties in the first year of the war—with his insatiable heedless lust for military glory. Brereton presided over four major high-casualty debacles as an air commander: destruction of his Far East Air Force on the ground in the Philippines; his Ninth Air Force low-level raid on the Ploesti, Romania, oil fields that lost 53 aircraft and crews; his friendly-fire attacks on Allied ground forces in Normandy, France; and his hasty, overly optimistic airborne plans that failed to secure the bridge at Arnhem in the Netherlands during Operation Market Garden.

These 15 assessments are admittedly subjective opinions and, to be fair, some appear hindsight-harsh in light of some commanders’ whole careers and the many outside factors that weighed on their combat decisions.

Still, The Worst Military Leaders in History is meant to be thought-provoking, and it surely is that.

Michael Robbins is a former editor of Military History magazine and MHQ, the Quarterly Journal of Military History.

* * *

A Memoir of a Life Defined by Conflict

The Good Captain: A Personal Memoir of America at War. R.D. Hooker Jr. Casemate Publishers (An AUSA Title). 298 pages. $34.95

By Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Retired Col. R.D. Hooker Jr.’s tale of his military career corresponds with the history of the U.S. Army from the post-Vietnam years to the global war on terror. Enlisting in the Army in 1975, Hooker later commanded an airborne platoon, company, battalion and a support brigade in the XVIII Airborne Corps.

In a long and distinguished career that spanned 32 years of service, Hooker participated in the invasion of Grenada; in Somalia during the humanitarian crisis; in Rwanda in the immediate aftermath of the genocide; with the first American unit to enter Bosnia; as a peacekeeper in the Sinai Desert; and in both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Hooker’s life has been shaped and defined by war. The Good Captain: A Personal Memoir of America at War is a memoir, not history. During his stellar career, Hooker, a frequent contributor to ARMY magazine, amassed the Distinguished Service Medal, three Defense Superior Service Medals, three Legion of Merit awards, three Bronze Star Medals and a host of additional medals. Hooker also served in several high-level Pentagon assignments and in the White House of four presidential administrations.

Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, will delight in Hooker’s recollections of his cadet days on the Hudson. So, too, will junior officers benefit from Hooker’s observations of the challenges and rewards of company command, which he notes “in many ways is the best it will ever get as an Army officer.” Commanders shape and inspire their units, and when they lead those units into combat, they bear “a crushing responsibility for accomplishing the mission, but also for the lives of [their] soldiers.”

To his credit, Hooker does not pull any punches with respect to political and military leaders with whom he served.

From his vantage point as a senior aide to Secretary of the Army Tom White in 2001, Hooker views then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld as a parochial politician whose managerial style became increasingly “intrusive and overbearing” in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. With the benefit of hindsight, Hooker posits that Rumsfeld and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, erroneously viewed Iraq as the “nexus of terrorism,” tied in some mysterious way to al-Qaida and 9/11.

Two military officers merit Hooker’s undying admiration: Lt. Gen. John Vines and Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster. Hooker characterizes Vines, commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division and later XVIII Airborne Corps, as “a tough guy … with a renowned combat record, but rigorously fair and objective.” As the commanding officer of the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment in Iraq, then-Col. McMaster emerges from these pages as “a brawny, bullet-headed cavalryman [who] crackled with intensity.” Hooker considers McMaster as “probably the best battlefield commander in the Army.”

Hooker sees striking similarities between America’s experience in Vietnam and the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He opines that the U.S. did not learn from its own history, making the identical mistakes in the global war on terror that America encountered in Vietnam four decades earlier. By tying ourselves to host national governments whose incapacity and corruption were themselves prime drivers of the conflict, the U.S. could not fix the social, political and economic problems of the region.

Secondly, facing an enemy that fought from privileged sanctuaries with the most powerful weapon of all—time—America’s national efforts were doomed to failure.

In the final analysis, The Good Captain is at heart a soldier’s story with compelling lessons from one of America’s most highly decorated field grade officers. This combat odyssey deserves a wide audience.

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He holds a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.

* * *

A Junior Officer Comes of Age in Vietnam

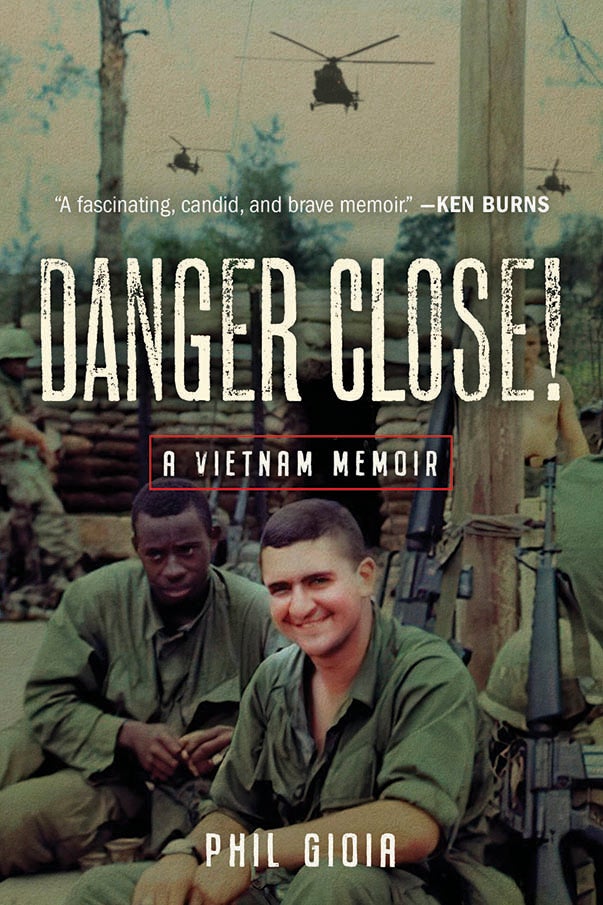

Danger Close! A Vietnam Memoir. Phil Gioia. Stackpole Books. 376 pages. $29.95

By Lt. Col. James Willbanks, U.S. Army retired

In 1968, 1st Lt. Phil Gioia, a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute, found himself leading a rifle platoon in the 82nd Airborne Division during the Tet Offensive. Wounded in April of that year, Gioia was evacuated to the United States. After recovering from his wounds, he again served in the 82nd Airborne, this time as a company commander at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

In April 1969, Gioia, who would soon be promoted to captain, returned to Vietnam for his second tour. He was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division as a company commander with the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment. At the time, the 1st Cavalry was operating in the III Corps Tactical Zone, north of Tay Ninh.

In Danger Close! A Vietnam Memoir, Gioia, as the subtitle suggests, provides a memoir of a young officer who served two tours in Vietnam with two divisions. That part of the book is fascinating and well written, but the book is more than a memoir of the author’s time in combat.

The first half of the book chronicles Gioia’s experience growing up in a military family during the Cold War. The author discusses in detail what it was like to be an Army brat growing up in far-flung places like Japan, Italy, Virginia, Alabama and West Point, New York. The reader can clearly see how these experiences molded and motivated a young man, who then went off to the Virginia Military Institute and, upon graduation, was commissioned in the infantry.

Having provided insight into his upbringing, the author then discusses his early experiences as a second lieutenant in the 82nd Airborne. With that preamble, Gioia describes what it was like to be sent with his platoon to Vietnam in the middle of the Tet Offensive.

During the conduct of operations around Hue, his unit discovered mass graves in the jungle that contained the bodies of civilians rounded up and executed by the Viet Cong when they seized control of the city. He goes on to detail his second tour operating along the Cambodian border.

In these parts of the book, Gioia is at his best describing the demands of leading American soldiers in combat. He accompanies this narrative with a running commentary that puts his experiences in the larger historical context of the war, as well as providing discussions of tactics, techniques and procedures.

As war memoirs go, this is an excellent addition to those that have come out of the Vietnam War. However, it has much more to offer. It provides a glimpse into the early life and motivations of young Americans who grew up during the Cold War, then went off to lead American soldiers in their own war in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

This book is a fascinating account, and most readers will find it hard to put down.

Lt. Col. James Willbanks, U.S. Army retired, is professor emeritus of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He is a Vietnam veteran and author or editor of 21 books, including Abandoning Vietnam and A Raid Too Far. He holds a doctorate in history from the University of Kansas.