Nov. 11 marks the 100th anniversary of Arlington National Cemetery’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, an idea the U.S. borrowed from France and Great Britain to recognize the remains of thousands of American soldiers that would never be identified and returned to their families.

On Armistice Day 1920, France and Great Britain each buried the remains of unknown casualties of World War I. For France, the burial took place at the Arc de Triomphe, a Paris landmark commissioned in 1806. Britain chose Westminster Abbey in London as the burial site for its unknown soldier, a structure consecrated in 1065.

One month later, U.S. Rep. Hamilton Fish III, a World War I veteran who continued to serve in the Army reserves, introduced legislation for the U.S. to also honor an unknown soldier. With no American equivalent to the Arc de Triomphe or Westminster Abbey, Fish proposed a special tomb be created at Arlington National Cemetery for this purpose.

It wasn’t an odd choice. The first military burial at Arlington was in 1864, when Pvt. William Christman was laid to rest on land set aside on a former plantation. His May 13 burial that year came just before the official June 15 order establishing the military cemetery. Christman, who served with the 67th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War, had died on May 11 at Lincoln General Hospital in Washington, D.C., of an illness, said to be either measles or peritonitis.

Arlington Cemetery, originally 200 acres, became a national cemetery when Civil War dead filled cemeteries in Arlington and at the Old Soldiers’ Home in the District of Columbia. Originally, it was intended to bury soldiers who died in area hospitals and had no other place for burial because their families were poor. Christman’s burial was an example. He’d enlisted less than two months before his death. His funeral had no flag, no family and no chaplain.

“Initially, being buried at a national cemetery was not considered an honor, but it ensured that service members whose families could not afford to bring them home for a funeral were given a proper burial,” according to a history written by Arlington National Cemetery. That changed in 1868 when “Decoration Day,” the first Memorial Day, as it became known, was celebrated on May 30, beginning an annual public tribute to those who had fallen. The celebration became so popular and crowded that an amphitheater was constructed in 1873 and soon, living senior officers started asking to reserve burial spaces.

Fish’s resolution passed Congress in March 1921, launching an effort to both design an appropriate tomb and select the remains of an unknown soldier. The resolution required only that this be an American who served in the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, died during the war and whose identity was not established.

After much discussion, the selection fell to an NCO, Sgt. Edward Younger, a twice-wounded World War I veteran who at 10 a.m. on Oct. 24, 1921, stood at a city hall in Chalons-sur-Marne, France, before four identical, flag-draped caskets. The remains had been exhumed from American cemeteries in France. Younger, assigned to Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 50th Infantry Regiment, American Forces in Germany, thought he was there to be a pallbearer, but he was handed a bouquet of pink and white roses by Maj. Robert Harbold of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps and told to pick the soldier to be honored.

Younger was left alone. “I walked around the coffins three times, then suddenly stopped,” he later said. “What caused me to stop, I don’t know. It was as though something had pulled me.” He stood at attention and saluted. “I can still remember the awed feeling that I had, standing there alone,” said Younger, who died in 1942 and is buried in Section 18 at Arlington National Cemetery.

The body of the unknown soldier traveled to Paris, then on to the port city of Le Havre. It was taken aboard the USS Olympia, a U.S. Navy cruiser that departed on Oct. 25, 1921, for the Washington Navy Yard, where it arrived Nov. 9, firing its gun in salute after the casket was taken ashore.

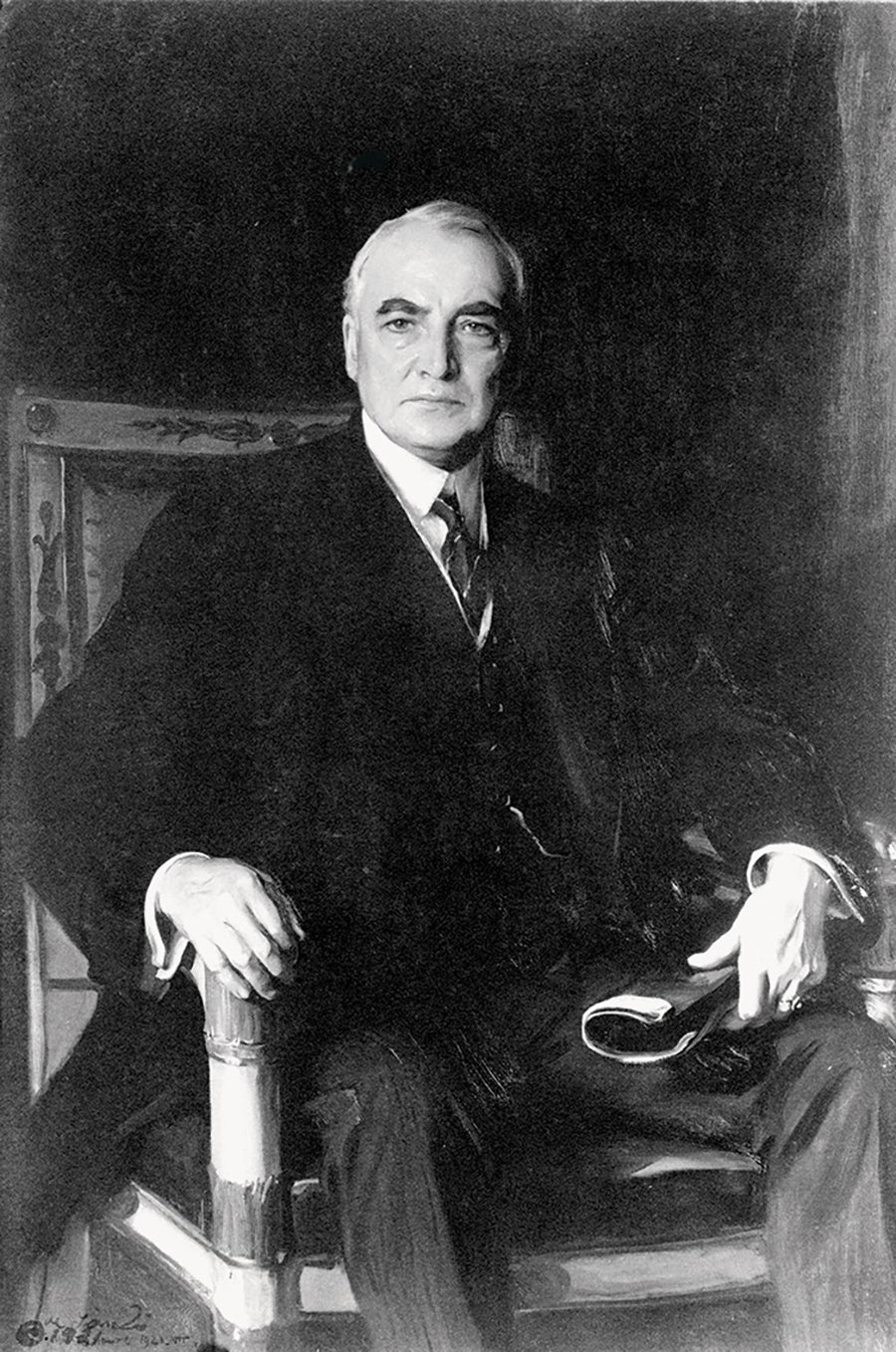

The casket was taken to the U.S. Capitol and placed in the rotunda. As the casket lay in state, an estimated 90,000 people paid their respects. Among those visiting was Gen. John Pershing, the American Expeditionary Forces commander who, along with President Warren Harding, would accompany the unknown soldier’s final trip to the cemetery.

Carried Away by Patriotism

A special report in The New York Times described the burial of a nameless soldier as unlike the ceremonies for Presidents Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield and William McKinley. “There were tears of sorrow then. There were tears today, but most of those who shed them were carried away by the emotion of the symbolism of patriotism which this unknown American embodied. …

“At Arlington, the nation’s military Valhalla, in the low Virginia hills which form a background for the capital city, the Unknown Warrior was placed in a marble sarcophagus, designed to be a national shrine like that under the Arc de Triomphe,” The Times said.

At 8:30 a.m. on Nov. 11, a ceremony began. Eight service members—soldiers and sailors—carried the casket down the Capitol steps in a ceremony overseen by Brig. Gen. Harry Bandholtz, the Military District of Washington commander who had served as provost marshal general in the American Expeditionary Forces. As the procession began, a group of Medal of Honor recipients and a group of Gold Star wives joined behind the caisson that passed the Supreme Court and the White House, then traveled through Georgetown and across a Potomac River bridge. The total distance was about 7 miles, The Times said. Along with Harding and Pershing, dignitaries included Supreme Court Chief Justice William Taft, a former president; former President Woodrow Wilson; and dignitaries from France, Britain, Italy, Belgium and Japan, The Times reported.

“Surrounded by the world’s greats, with none of them too great to bow in homage, this dead boy’s funeral was still no pageant, no spectacular drama, no worldly show. It was more a benediction,” The Times wrote. “Washington has witnessed many notable ceremonials, but never one like this.”

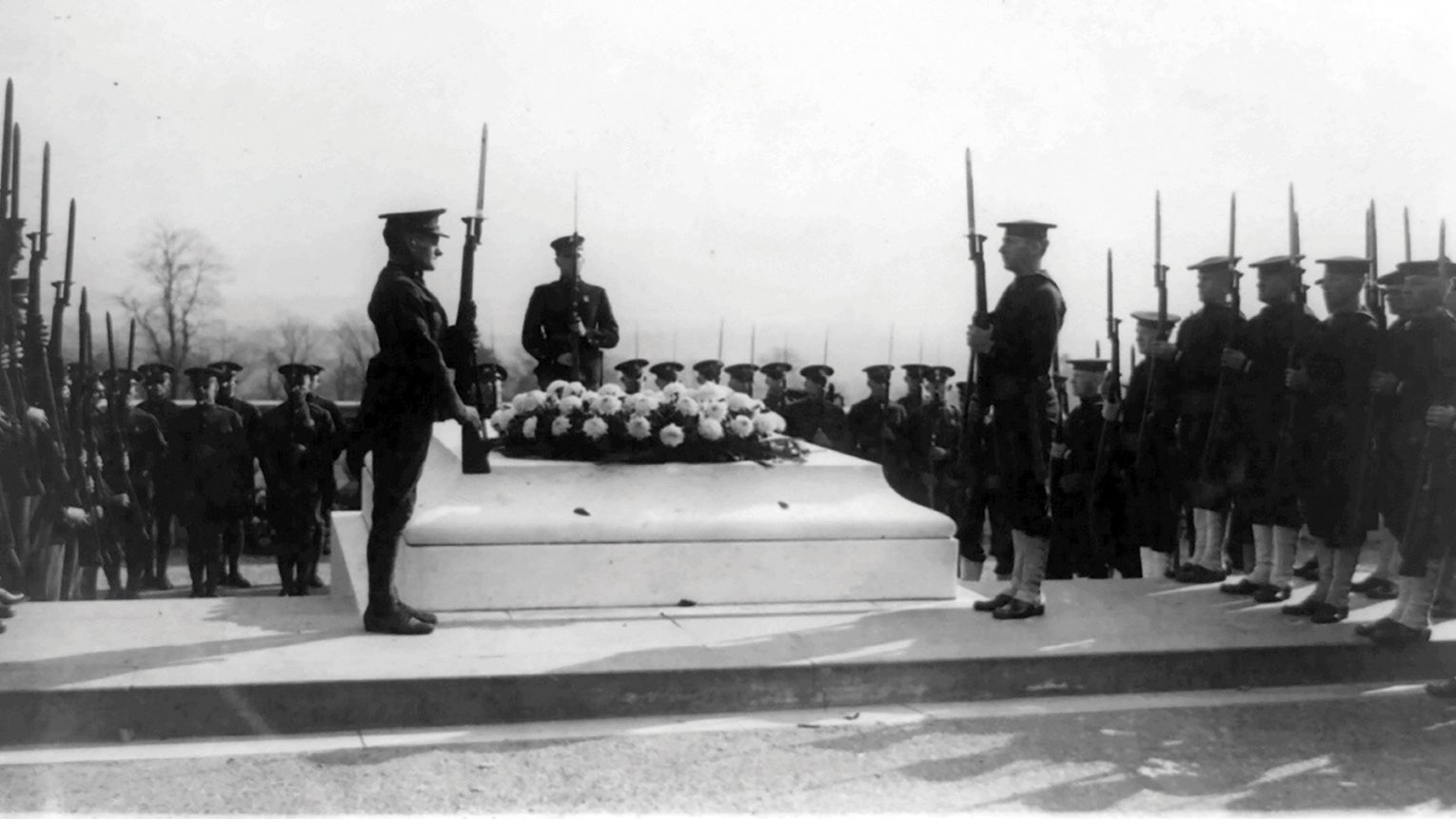

The funeral procession arrived at the cemetery at 11:40 a.m., greeted by a crowd of more than 100,000. The spectators gathered in and around the amphitheater as the coffin was lifted from the caisson and placed on a black-draped catafalque, The Times reported. The crowded included representatives of most of the World War I alliance, a group of nurses and wounded soldiers from Walter Reed General Hospital, as it was known at the time, and many civic organizations.

Harding was the main speaker, saying the soldier about to be buried in the tomb “might have come from any one of millions of American homes.”

“Hundreds of mothers are wondering today, finding a touch of solace in the possibility that the nation bows in grief over the body of the one she bore to live and die, if need be, for the Republic,” Harding said.

“We do not know the eminence of his birth, but we do know the glory of his death. He died for his country, and greater devotion hath no man than this. He died unquestioning, uncomplaining, with faith in his heart and hope on his lips, that his country should triumph and its civilization survive,” the president said.

“As a typical soldier of this representative democracy, he fought and died, believing in the indisputable justice of his country’s cause,” Harding said. “This American soldier went forth to battle with no hatred for any people of the world, but hating war and hating the purpose of every war for conquest.”

“Today’s ceremonies proclaim that the hero unknown is not unhonored,” Harding said.

The remains were placed in a simple tomb on the edge of the amphitheater. It was a three-level marble structure covered with a stone slab. The original tomb wasn’t much to look at, but there were big plans.

Military Guard Assigned

There were no tomb guards in 1921. A civilian daytime guard was assigned in 1925 to stop picnics from being spread out on the tomb. A military guard was assigned to the post beginning March 24, 1926.

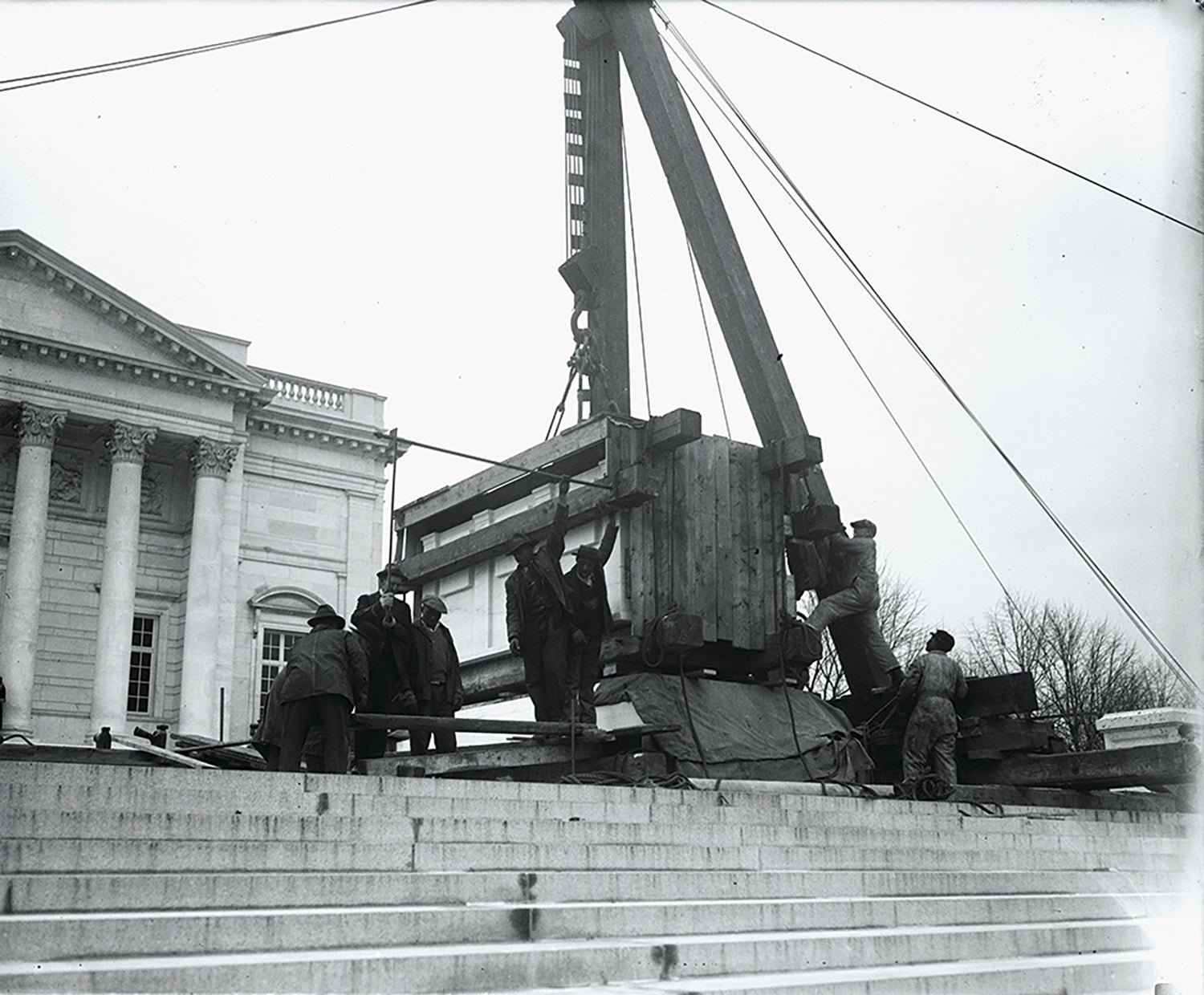

On July 3, 1926, the stone slab was replaced with marble, and a competition was launched to build a monumental sarcophagus atop the tomb. Construction wasn’t completed until April 1932 because of a variety of problems that included delivery of a flawed block of white marble that had to be replaced.

A 24-hour guard of the tomb began on July 2, 1937.

In 1958, World War II and Korean War unknown service members were added to the tomb. In 1984, remains were interred from a Vietnam War service member, but 14 years later, the remains were exhumed and identified as Air Force 1st Lt. Michael Joseph Blassie, a pilot shot down in 1972. He was buried in Missouri at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery on July 10, 1998. There have been no unknowns added to the tomb in subsequent years because of advances in DNA testing and other forensic techniques.

* * * * * *

A Sentinel’s First Walk

Karli Goldenberg, Staff Writer

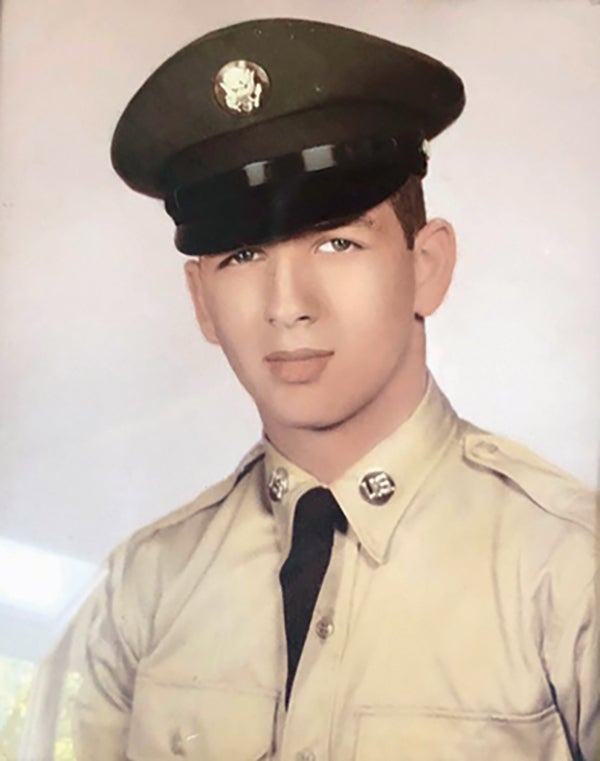

Richard Azzaro spent all day anticipating his first walk at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, endlessly polishing his shoes and brass.

But when the then-18-year-old Azzaro completed the guard change at Arlington National Cemetery, something happened, he said. “It suddenly felt like I had a friend out there,” he said. It could have been his training and muscle memory kicking in, but Azzaro is convinced that he felt a calming presence “letting me know I was going to be OK.”

Azzaro, who was a specialist fourth class when he served as a tomb guard from 1963 to 1965, spent most of his time as a sentinel and relief commander, who oversees the changing of the guard.

Soldiers have watched over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery since March 1926, when troops from nearby Fort Myer, Virginia, were assigned to guard the site during daylight hours. Since July 1937, the tomb has been under constant watch, with soldiers standing guard 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

The 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, known as “The Old Guard” because it is the oldest active-duty infantry unit in the Army, has stood watch over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a “distinguished duty,” since April 1948, according to the Arlington National Cemetery website.

Making an Impact

Sgt. Gabriel Silva, who has served six years in the Army, also said he was nervous on his first day as a sentinel, but his nerves were tempered by his potential to make an impact.

“I was nervous but excited. Just knowing the history of this place and knowing what it entails and the potential to create a legacy here, something bigger than myself, was something that I was looking forward to on my first day,” Silva said. “But just being part of the mission, my first time here was something special.”

For Silva, the desire to become a sentinel came early. A sixth-grade field trip to the cemetery sparked his calling. “It was something I always remembered,” he said. “So much so that when I came back home, I told my mom that I wanted to be buried in the Arlington National Cemetery.”

“Coming from Brazil to the United States, the United States gave me so much and made such a better life for me and my mom and my family now,” Silva said. “So, finding a way to give back to our country, and to show that patriotism and to show those that came before us, I found this was the best way I can do it by being a tomb guard.”

After enduring a grueling selection process and embracing the mission of being a tomb guard, there comes a time when the mission will embrace the tomb guards themselves, said Azzaro, president of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Foundation. The educational foundation promotes “the higher meaning” of the tomb, according to its website.

Tomb guards spend much of their time training and “giving [themselves] up completely,” Azzaro said. “There will come a time when the mission will turn on you and embrace you. At that moment, that’s when you become a tomb guard.”

Ultimate Sacrifice

Spc. Brendan Meier, who has served for three years in the Army and joined The Old Guard after basic training, said the mission embraced him.

“We’re in this cemetery with hundreds of thousands of people that have fallen in wars fighting for their country over the years, but there’s only just over 3,000 unknown soldiers, and just these four, now three, that are … interred up there,” in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Meier said. “It’s so important, because in addition to making the ultimate sacrifice of their lives … they sacrificed their identity.”

On Nov. 11, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier will mark its 100th anniversary. As the centennial neared, Silva said it put into perspective how many people have come together to honor the unknowns and the legacy of The Old Guard. Despite the passage of time, he said, The Old Guard’s mission has remained constant.

“Not much has changed in the perspective of … honoring and remembering those that gave … not only their lives, but their identities,” Silva said. “It’s still something that makes us American and puts us together into one despite who we are, what we do [and our] background, whatever it may be.”