November 2021 Book Reviews

November 2021 Book Reviews

Taking the Long View of Modern Wars

Blood, Metal and Dust: How Victory Turned into Defeat in Afghanistan and Iraq. Ben Barry. Osprey Publishing. 582 pages. $30

By Brig. Gen. John Brown, U.S. Army retired

Ben Barry, a seasoned battalion and brigade commander and a military thinker with impressive credentials, has authored Blood, Metal and Dust: How Victory Turned into Defeat in Afghanistan and Iraq, a splendid one-volume history of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. As a British author, he gives due attention to the participation of America’s NATO allies, bringing alive contributions American authors may be prone to overlook.

Barry’s accounts of operations are gripping, succinct, comprehensive and altogether readable. His appreciation of the big picture is ably reinforced by his demonstrated understanding of combat at the grassroots level.

Barry develops his story chronologically, albeit packaged between the two major theaters. A robust preface and expansive first chapter provide the strategic and institutional setting for 9/11. Then, two chapters cover Afghanistan from 2001 to 2005. Following this, seven chapters take Iraq from invasion through 2020. Barry then returns to Afghanistan to cover 2006–20 in three chapters. A short postscript on COVID-19 is followed by a summary chapter covering lessons learned.

The reader benefits from maps and endnotes throughout, along with a glossary of terms and acronyms and an extensive recommended reading list.

The back and forth between theaters is not jarring, tracks national priorities during the respective periods, and allows one to follow each theater with continuity. The operational history is particularly good, bringing battles such as those for Fallujah and Helmand Province to life. The battlefield dominance of allied forces in standup fights becomes obvious, amply demonstrated in the initial invasion of Iraq or the U.S. 1st Armored Division’s Extension Campaign, for example.

More subtle operations receive scrutiny as well, such as the Anbar Awakening and in excellent dissections of the battles for Basra. Barry ends each chapter with an “Audit of War,” a particularly helpful summary of the chapter’s contents and lessons to be drawn from them.

As excellent as Barry’s narrative is, it does seem to end abruptly. After 252 pages about Iraq, for example, America still seems to be on top. Then, in the section titled “Maliki Steals the 2010 Election,” one thing leads to another, and events unravel in eight pages.

Similarly, after 134 pages, things look good in Afghanistan—a major Taliban effort to reverse the results of President Barack Obama’s Afghan Surge has failed, and Afghan government forces successfully secure nationwide elections. Then, Afghan leaders fall out with one other, U.S. forces draw down and the situation erodes within 16 pages. The thoughtful summary chapter, “Bloody Lessons,” does not quite redress the abruptness of these downslopes.

The book’s subtitle, “How Victory Turned into Defeat in Afghanistan and Iraq,” is better served with respect to why the U.S. had the impression of victory than as to why it has come to an impression of defeat.

It may be that Barry is writing military history, and the necessary explanations are not really military. It may also be that he has written an excellent first draft on a subject not ready to go final. Afghanistan and Iraq began as episodes of a more expansive global war on terror. This is far from over, and has metastasized into dozens of venues that also deserve American attention. As unhappy as the U.S. is with the results thus far, things have gone considerably worse for Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, Moammar Gadhafi, the Iraqi Baathists and al-Qaida.

There must be a lesson in there somewhere about the wisdom of attacking the U.S.—just as Barry’s narrative offers lessons about the wisdom of biting off more than we care to chew.

I strongly recommend that you read this book. I also fervently hope Barry writes an updated version in about 10 years’ time.

Brig. Gen. John Brown, U.S. Army retired, served 33 years in the Army, with his last assignment as chief of military history at the U.S. Army Center of Military History. The author of Kevlar Legions: The Transformation of the United States Army, 1989–2005, he has a doctorate in history from Indiana University.

* * *

Native Americans Take Up Arms for US

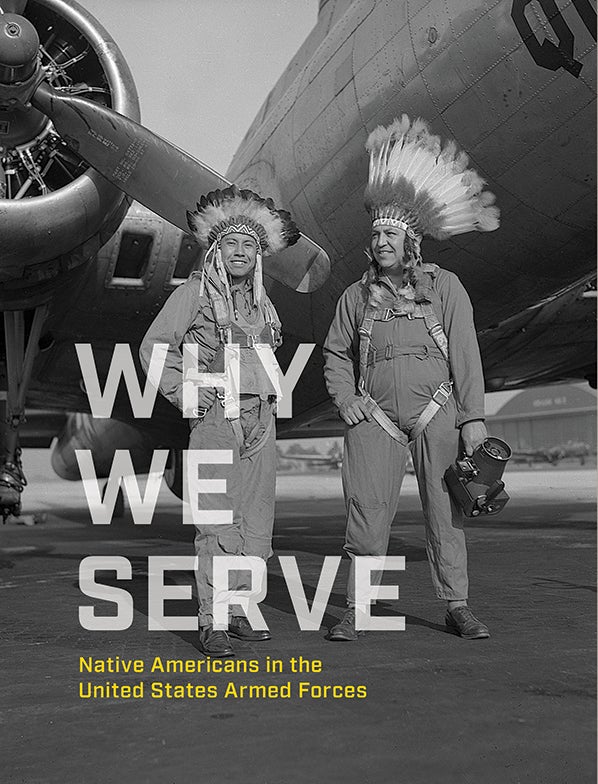

Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces. Alexandra Harris and Mark Hirsch. National Museum of the American Indian Smithsonian Institution. 240 pages. $29.95

By Col. David Napoliello, U.S. Army retired

On Veterans Day 2020, in a ceremony with coronavirus-limited attendance not widely reported by the media, a new memorial was dedicated on the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian. After more than two centuries of faithful service by American Indians, Alaska natives and native Hawaiians to the U.S., the National Native American Veterans Memorial was opened in Washington, D.C.

Some may be surprised that America’s indigenous people served a country and government with whom they had such a checkered history. Despite being driven from their homelands and being forced to abandon their culture, generation after generation of native peoples served in the U.S. armed forces—usually in numbers disproportionate to their representation in the total population.

“In our heart, this is still our land, so we’re fighting still for our land,” one native woman veteran explains in Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces.

Why We Serve is an anthology spanning the centuries of service by young men and women who left the confines and kinship of their tribal homes to take up arms for their homeland and country. Contributors to Why We Serve are a distinguished gathering of eminent Native American historians and authors led by the Smithsonian museum’s Alexandra Harris and Mark Hirsch.

The authors visit America’s wars and explore the circumstances confronting its indigenous populations at the time and what prompted their members to don the uniform. Why We Serve includes stories and vignettes from Native American veterans that deepen the reader’s appreciation of the native cultures and warrior ethos inculcated into each volunteer.

Each native veteran endured an added burden. Almost universally, they were the first indigenous Americans that whites with whom they served had encountered. Their race would forever be judged in the eyes of their brothers and sisters in arms by their individual conduct as a person, soldier and warrior.

While the reasons for indigenous people’s military service have varied over the centuries, there are always two simple yet powerful emotions involved: honor and respect. Those who served did so in honor and respect of the traditions of their family, tribe and Indian nation. Warriors served to protect their homes, their land and their country. Military service is a self-perpetuating tradition, revered and respected across the generations.

Besides honoring their traditions, military service also afforded indigenous people opportunities for educational and economic mobility. Military service held out the prospect of exploring new horizons and the chance to prove they could be patriotic Americans and still be members of tribal nations.

Countless indigenous Americans have distinguished themselves through acts of valor, including 34 who received the Medal of Honor. Thirty of that number were soldiers, three were sailors and one was a Marine. Widely heralded among those who served were the Code Talkers of both world wars, warriors who used their mastery of tribal languages to help achieve victory on the European and Pacific battlefields. Code Talkers of more than 20 tribes were honored with Congressional Gold Medals authorized by the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008.

This incredible heritage of more than two centuries of service comes to life in the pages of Why We Serve with its first-person accounts of the wartime experiences of the Native Americans who served. The rich narrative is augmented by a superb and expansive collection of photographs, maps, paintings and illustrations reflective of the people and their service.

Col. David Napoliello, U.S. Army retired, a Vietnam veteran, served in field artillery, comptroller, and program management command and staff assignments through the DoD level. After retiring from the Army, he was vice president for global strategy and planning for a major defense corporation and vice president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund.

* * *

Veteran Provides Blow-by-Blow Account of Overlooked Battle During Vietnam War

Courage Under Fire: The 101st Airborne’s Hidden Battle at Tam Ky. Lt. Col. (Ret.) Ed Sherwood. Casemate. 352 pages. $34.95

By Matthew Seelinger

The 101st Airborne Division fought two major operations in the Vietnam War during May 1969. The first, the 3rd Brigade’s bloody and controversial battle for Dong Ap Bia, became notorious as the battle for Hamburger Hill. The other, codenamed Operation Lamar Plain—which saw the 1st Brigade fighting the North Vietnamese Army around Tam Ky and on Hill 376—has received little, if any, attention by historians.

Retired Lt. Col. Ed Sherwood, a veteran of Operation Lamar Plain, looks to correct this deficiency in his book, Courage Under Fire: The 101st Airborne’s Hidden Battle at Tam Ky.

Sherwood, who commanded a platoon in Company D, 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, during Operation Lamar Plain, says he wrote Courage Under Fire for three reasons: first, to leave a legacy of the faithful service of the soldiers who served in Vietnam; second, to encourage and instruct young people who are currently serving or considering joining the Army; and third, to “make known the 101st Airborne’s hidden battle at Tam Ky” from May 15 through June 12, 1969.

Using interviews with soldiers who took part in the fighting, after-action reports, accounts of his own experiences and a host of other primary and secondary sources, Sherwood provides a blow-by-blow account as American and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces clashed on Hill 376.

Written and presented like a series of after-action reports, Courage Under Fire provides readers a thorough examination of Operation Lamar Plain from the point of view of soldiers on the ground, particularly those of Sherwood’s company. The author provides great detail on all aspects of the fighting, including the type of equipment and weapons used by American and NVA forces; American use of firepower, such as artillery and close air support from attack helicopters and fighter-bombers; and tactics employed by both sides.

Each chapter focuses on a single day or multiple days, depending on the amount of combat over a particular period, with Sherwood providing a summary of casualties and medals for the soldiers of his battalion.

While Sherwood commends all the soldiers with whom he served, he reserves high praise for the combat medics of his unit. Sherwood himself was badly wounded two weeks into the battle and recalls the medic assigned to his platoon who, like many, was known as “Doc” to the men.

The medic who treated Sherwood was a conscientious objector who nonetheless served bravely in Vietnam. Sherwood later states in researching the book that none of the veterans he consulted could remember the medic’s actual name and sadly, he could find no information about him despite numerous efforts over a three-year period.

In addition to providing extensive details of combat operations at Tam Ky and Hill 376, Sherwood includes a wealth of valuable information in nine appendices and a glossary of terms and abbreviations. Courage Under Fire would benefit from some tighter editing—readers will find some typos and the word “ordinance” is used in place of “ordnance” on several occasions.

These, however, are minor quibbles in an otherwise excellent study of an overlooked battle of the Vietnam War.

Matthew Seelinger is chief historian of the Army Historical Foundation and editor of the foundation’s quarterly magazine, On Point.

* * *

Commander Plays Crucial Role During Normandy Beach Landings on D-Day

D-Day General: How Dutch Cota Saved Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944.

Noel Mehlo Jr. Stackpole Books. 400 pages. $29.95

By Lt. Col. Tim Stoy, U.S. Army retired

D-Day General: How Dutch Cota Saved Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944 does an excellent job of describing how critical Brig. Gen. Norman “Dutch” Cota’s leadership was during the Normandy landings. A detailed discussion of the tactical situation at Omaha Beach and Cota’s outstanding leadership there is the strength of this book and demonstrates the accuracy of the book’s subtitle.

Author Noel Mehlo Jr. provides an overview of Cota’s early life and military career before covering his impactful work at the onset of World War II with the 1st Infantry Division, first as operations officer and then as chief of staff, in the amphibious training for the landings in Northern Africa in November 1942.

After a superb performance in the landings, Cota was promoted to brigadier general and sent to Europe to help plan for Operation Overlord in Normandy, France. In October 1943, he assumed the duties of assistant division commander of the 29th Infantry Division and helped prepare it for the invasion. It is clear from this section of the book that Cota was a solid, no-nonsense, confidence-inspiring leader.

Cota played a crucial role in the assault on the beach on June 6–7. His fearless leadership in the maelstrom of combat among dazed and fear-paralyzed men galvanized them into action. His coolness under fire and his leadership instincts were exemplary. He was in the right place at the right time, made the right decisions and took the correct actions—exactly what is expected of senior leaders in combat.

The narrative explains that Cota’s mission was to establish the 29th Infantry Division’s forward command post and control the assault waves as they arrived. Upon Cota’s arrival an hour after the initial wave, he found the men jammed on the beach, having landed in a heavily defended sector. Many leaders were dead or wounded, there were severe casualties, and many remaining soldiers were terrified.

In the following 30 hours, Cota would cover 17 miles back and forth along the beach, encouraging soldiers, providing direction and coordinating engineer support, all the while moving from position to position seemingly without concern for his own safety under heavy enemy fire. He identified the weakest point in the German defenses, arranged for demolitions to breach the tank wall there, and got the troops off the beach. He then continued to organize and lead the forward elements as they continued to clear exit avenues off the beach.

For this outstanding performance, Cota was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and, although not part of this book, he also would be promoted to major general and given command of the 28th Infantry Division. Clearly, he was an inspiring combat leader worthy of emulation.

However, the book reads like an extended award justification. There has been a decadeslong effort to convince the Army to upgrade Cota’s Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor. The growing trend of upgrade efforts over the past several years effectively calls into question the judgment of awards boards, chains of command and Army policies in World War II. This singular focus on the Medal of Honor for valor in combat slights the high stature of the Distinguished Service Cross, which is awarded for “extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy.”

The final chapter of D-Day General details the to-date unsuccessful upgrade effort, and appendices include letters of support from dignitaries. If the reader can get past the incessant drumbeat of upgrade, upgrade, upgrade and focus on the story of Cota’s life, career and actions on D-Day, they will gain a clear picture of just how impressive Cota’s combat performance was on Omaha Beach.

Lt. Col. Tim Stoy, U.S. Army retired, is a military historian. He served 31 years in the Army as an infantry and foreign area officer.