Brainstorming is a valuable technique when an organization must develop the plan for a large-scale or complex project or an enduring program for which there are ambiguous mission parameters, multiple constituencies, and multiple references—or worse, none—to guide the enterprise. Brainstorming helps staff generate ideas, solutions and action steps to inform the venture. It also supports the building of strong, engaged teams.

Typical issues that might lend themselves to an organization’s use of brainstorming are doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel and facilities assessments; after-action reviews; and examining ways to free up “white space” on the unit calendar.

When now-retired Col. Darrell Katz was given the unenviable task of closing Flint Kaserne in Bad Toelz, Germany, by July 1991 and relocating the organizations based there, he employed brainstorming to generate a robust set of action steps to ensure the move was conducted with the least disruption.

Returning control of a U.S. base to the German government, and moving the unit and families, were formidable tasks. Armed with very little in the way of guidance other than an order to close Flint and a date for turnover, Katz’s team set to work.

His unique employment of inclusive brainstorming, and his insights into managing complex and long-range tasks, resulted in a plan that included input from many constituencies; enjoyed “buy-in” by the organizations, members and families involved; and incorporated management activities that ensured all activities were completed on time.

Review the Rules

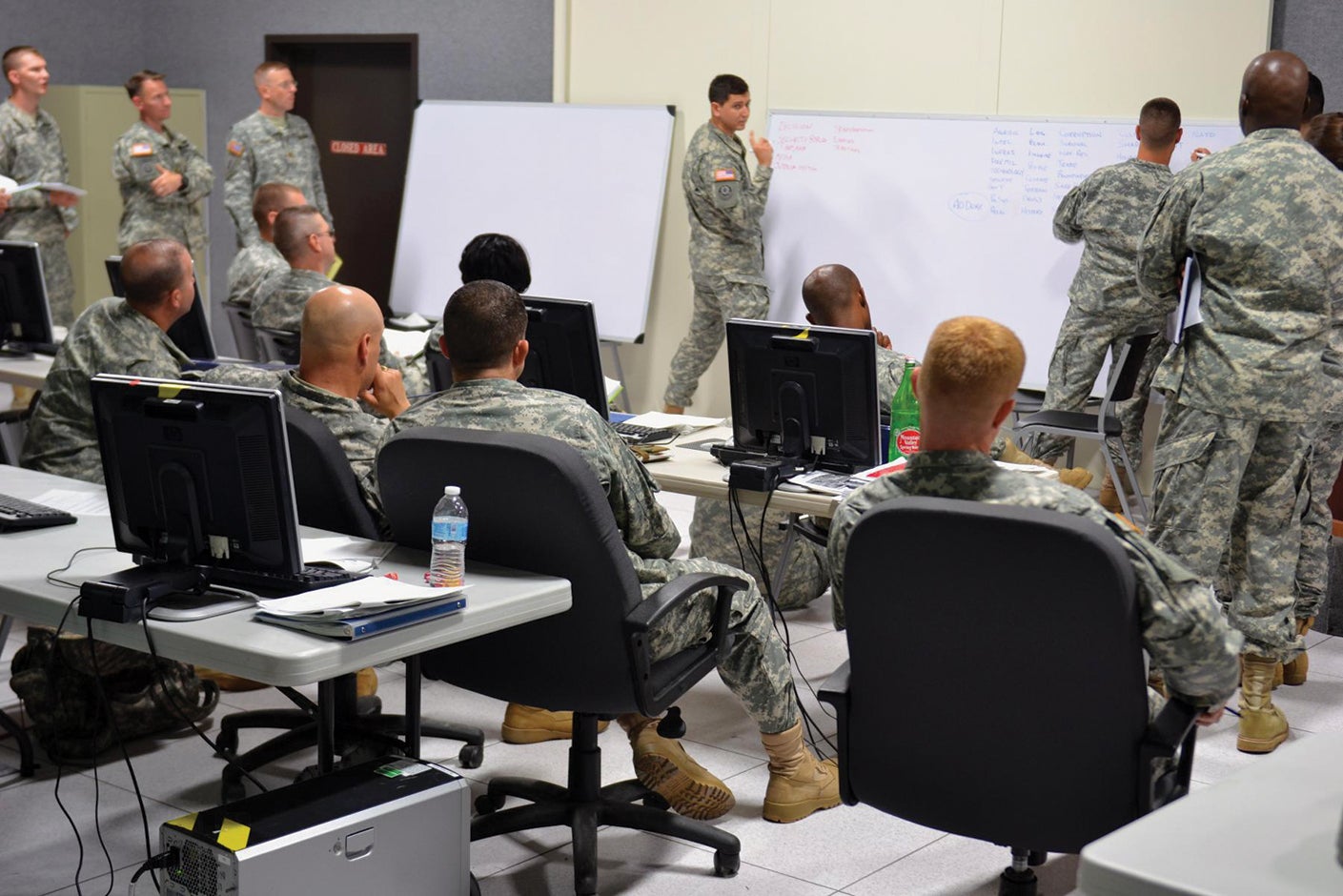

If you are considering a brainstorming session, review the brainstorming rules of the road. Don’t assume that everyone understands the process and will abide by the rules. Without a brief discussion of the fundamentals and routine reminders of the guidelines, the brainstorming process will be disrupted because ideas will be judged and distracting discussions will begin. The use of a skilled facilitator can help in the execution.

One question that should be asked early in the process is, “Who else should be part of this planning team?” Also, a key to an effective session is to ask the right question in the right way. The brain will go to work on any question asked. For example, when asked “Why can’t we…?” the brain will churn and provide a long list of reasons why you can’t. If the question is framed, “How can we…?” the brain will work just as hard on providing a comprehensive list of activities to solve that puzzle.

A business consultant once told me that in most situations, all the information that an organization needs to solve a problem already resides in the employees. His task was giving voice to the employees who had the knowledge and skills, and teasing the information out for the managers.

When an executive begins to express opinions too early in the process or to overrule recommendations, the brainstorming climate is dampened and the buy-in is less than optimal. In brainstorming, the process is more important than the plan.

Buy-in is a critical element in executing a plan. “People support a world they helped create,” according to Dale Carnegie, the famous public speaker on self-improvement. The more involved an individual is in crafting a solution or developing a plan, the more energetically he or she will support the final plan of action.

Create Support

Including seasoned members of lower-echelon organizations along with junior officers and enlisted personnel helps an organization create linkages of support throughout the unit. This increases the conviction that all voices were heard and concerns addressed.

In the case of Flint Kaserne, the plan required seemingly endless tasks. A short list included selecting the future home from a handful of available bases that would be vacated in the overall reduction of U.S. forces in Germany; identifying requirements and coordinating adequate family housing, headquarters, team rooms and barracks; arranging for training to continue until the last possible day before movement and re-commencing immediately after moving; and identifying and coordinating social and official events in support of the movement to the next home.

As the project owner, Katz used what in a civilian context might be called focus groups. He included several constituencies from outside the normal planning staff. After the staff had developed the basic plan and timeline of activities using the time-honored reverse-planning process, these other constituencies were invited to offer their insights. They often identified activities that were not normally at the top of the mind of the project manager.

These voices included personnel from facilities and organizations such as dining facility, motor pool and arms room; commissary and exchange; and medical and dental clinics. Spouses provided their concerns; the unique requirements of special-needs children were also addressed. Key civilian leaders from Bad Toelz were consulted. Flint Kaserne leaders met with the counterparts of those civilian friends at the new communities.

As the search for a new home narrowed, engineers and security personnel were consulted to determine the suitability of each potential home for the 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group. Would the upper floors support the safes? Could elevators be constructed to facilitate movement of heavy team gear?

Well-facilitated planning sessions should result in a comprehensive list of activities for the key staff to arrange and sequence in the most logical order. The input of these constituents informed a robust plan that was designed to execute all the activities while maintaining a rigorous training schedule, with the least disruption in the unit’s operations tempo and home life.

Manage Plans

Most projects don’t fail because of poor planning; they fail due to faulty execution. As one sage remarked, “Even a hole has to be managed.” Brainstorming to determine the action steps for managing the execution will pay dividends. It’s difficult to grumble about the management of an activity when you have a hand in creating the management plan.

There is a tendency to develop what project management guru Eliyahu M. Goldratt described in the book Critical Chain as the student syndrome: building in safety factors and then waiting until the last minute to work on a project. Leaders need to be aware of these safety nets and squeeze this excess from the plan during the development stage.

Using a simple plan of activities and milestones (POAM), an executive can easily determine the status of a project and make corrections early. A well-constructed POAM for executive-level management of a project includes four elements: a no-later-than deadline; the task, simply stated; who is responsible for the task; and comments or notes such as what must happen before this activity can be acted upon.

To maximize the effect, the senior leader should be the project owner. Ownership by the rater encourages attention and support of all departments. Katz, by word and deed, left no doubt who was in charge.

Katz’s participation and continued interest ensured that energy levels remained high throughout the execution phase. There is magic in the executive showing personal interest. Attending the meetings sends a clear signal that this project is important to the leader.

However, the executive will probably not be involved in the day-to-day execution of the activities; the project manager ensures activities remain on schedule between meetings with the executive. The project manager also conducts supplemental meetings to discuss and coordinate activities.

Develop After-Action Report

As the project comes to a close, take the opportunity to review and analyze what went right as well as what could have gone better. This is a great time to develop an after-action report.

Brainstorming—especially inclusive brainstorming—is a powerful tool to analyze a task; inform a robust plan; assist the executive in managing the execution; and prepare for the next complex, long-range or enduring project. Regularly managing activities ensures all supporting tasks are completed on time. Personal attention by the senior leader—the project owner—prevents the loss of enthusiasm during a long-range project.

Including a broad and deep array of individuals and subordinate units throughout the organization promotes greater understanding of the activities; increases buy-in; and reinforces cohesive teams.

However, gathering all the information from the multiple brainstorming sessions with heterogeneous constituencies will result in nothing if you don’t roll up your sleeves and go to work on the plan. As noted management consultant Peter Drucker once said, “Plans are only good intentions unless they immediately degenerate into hard work.”