Welcome (Back) to the Jungle

Welcome (Back) to the Jungle

by MAJ Karl Rauch, USA

Land Warfare Paper 160, April 2024

In Brief

The New Guinea Campaign of World War II provides a valuable case study in evolutionary tactics and operational approach toward jungle warfare. It underscores the vital need for armies to adapt their strategies, operational planning and individual soldier resilience when faced with the multifaceted challenges of tropical environments.

Reflecting on the historical experiences of Australian and American experiences during World War II illuminates the stark transformations required in military doctrine to contend with the jungle’s terrain and biodiversity.

Despite technological advancements, the dense and demanding jungle environment necessitates a deep understanding and specialized preparation. This unique environment may prove an equalizer toward emergent technologies that have become the keystone of other battlefields.

The synthesis of operational and tactical experiences from the New Guinea Campaign serves as a means both for past lessons learned and to incorporate these insights into modern military doctrine, emphasizing the indispensable role of adaptive approaches in overcoming the jungle’s relentless challenges.

The essence of jungle warfare, distilled from the New Guinea Campaign, remains a critical component of military readiness and operational planning. Contemporary forces must embrace the complexities of fighting in tropical environments with informed agility and foresight.

Introduction

The war in the South Pacific was a struggle between outsiders. To those from the outside, the South Pacific was a wretched battlefield, one of the worst in history. Into this savage world, three governments sent their young men to fight each other.

—Eric Bergerud, Touched with Fire

Since the founding of the United States, American Soldiers have conducted military operations in jungle or tropical forest environments. From the Carolina swamps during the American Revolution and Civil War to the rice fields of Vietnam, such environments present unique and unforgiving challenges to the individual warfighter. During World War II, the American and Australian armies demonstrated a turning point in how modern armies conducted military operations in a jungle environment during large-scale combat operations. The New Guinea Campaign of 1942 to 1945 offers critical insights into a 21st-century land force preparing for potential conflict in similar environments. In 2011, President Barack Obama announced America’s Pacific Pivot.1 This statement began a sea change for the U.S. Army. Though it would take ten more years for the United States to remove itself from the mountains of Afghanistan, the Army has embraced a future in the Pacific.

Following President Obama’s announcement, the Army saw a rapid expansion of Pacific-focused training and operations, including revitalizing the Army’s Jungle Operation Training Center hosted by the 25th Infantry Division’s Lightning Academy on Oahu, establishing a Pacific-focused national and international training center with the Joint-Pacific Multinational Readiness Center (JPMRC) and rapidly growing security cooperation across the international date line. As we look forward to the following decades and continue to shape the Army for its role in a multidomain conflict across the Pacific, the Army must expand its understanding and capability of jungle warfare beyond the tactical level. The fight for New Guinea offers such an opportunity for understanding.

When asked what jungle warfare looks like, the observer will likely respond by painting a picture that describes the mythical snake-eater stalking through waist-high swamps, silently seeking an invisible enemy alongside a small group of elite teammates. Indeed, most of the literature that discusses warfare in a jungle or tropical forest environment focuses exclusively on tactical operations at the small unit level. Although recently updated, in 2020, the Army/Marine joint manual, ATP 3-90.98/MCTP 12-10C, Jungle Operations, still offers the organizational planner little beyond survival best practices, navigation techniques and generic environmental considerations when planning small unit operations. It offers little practical value beyond the tactical level. By examining the American and Australian armies during the World War II New Guinea Campaign, this monograph seeks to expand the conversation of training for and conducting operations in a jungle environment beyond tying knots and purifying water. Additionally, this article can serve as an introduction to land warfare in a jungle environment for Soldiers heading to their first posting in such a location.

Modern armies have struggled to adapt operational methods of warfare to a jungle or tropical forest environment. Only through active experimentation and trial by fire did organizations such as the U.S. and Australian armies during World War II make strides in recognizing the unique impacts the jungle environment had on the tactical and operational levels of war. That campaign demonstrates that unique environments like the jungle forced these armies to change how they considered basing, operational reach and endurance factors at the individual and organizational levels. These lessons must be considered as the contemporary U.S. Army trains and prepares for contingency operations across the Pacific in the coming century. However, it remains imperative that any attempts to apply lessons and concepts from a nearly 100-year-old conflict to the modern battlefield must account for differences, lest they run afoul of Clausewitz’s warning: “The further back one goes, the less useful military history becomes, growing poorer and barer at the same time.”2

To compare the effects of a jungle environment on military operations, we will consider the Australian and American experiences in the form of an environmental distinction: assessing the Australian Army through an inland lens via the Kokoda trail campaign and assessing the American Army through an amphibious lens via operations after the capture of Buna and Gona. Shaped largely by the Kokoda trail campaign from July to November 1942, The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) would undergo the greatest revolution in the history of the Australian Army.3 As these inland jungle operations shaped and forced this transformation in the AIF, the American forces under General MacArthur across the Southwest Pacific Area had an experience similar to yet broader than their Australian counterparts. Crucially, the Americans were the principal force conducting amphibious operations across the theater. Therefore, this article will explore the relationship between the coastal jungle environment and how General MacArthur planned and executed his coastal operations along the north coast of New Guinea during Operation Cartwheel in the summer of 1943. Finally, this paper will turn to the modern era, where, through a review of contemporary research reports and studies, it will overlay the Army’s current doctrine to the prevailing thinking regarding potential conflict across the Pacific theater; this will identify crucial gaps, lessons learned or areas for further research to better prepare today’s army for conflict in and around this one-of-a-kind combat environment.

Figure 1: The Island of New Guinea and the Owen Stanley Mountains4

Green Hell

Heaven is Java; hell is Burma, but no one returns alive from New Guinea.

—Japanese saying, from James P. Duffy, War at the End of the World

To explore and address the research question proposed in the previous pages, the reader must understand that the jungle environment so frequently addressed in the literature surrounding the New Guinea Campaign is an antagonist in and of itself throughout the story. Veterans of the campaigns throughout tropical rainforest environments often would recall the horrors of the environment before those of combat. Henry Gullet perfectly captures the essence of the jungle as a malicious entity: “sunless, dripping, curiously silent . . . yet somehow alive, watching, malignant, dangerous.”5 The word jungle, to many, invokes a particular picture. It is something exotic and sensory, usually informed by pictures from the movies. In some ways, that stereotypical vision of a jungle is actually correct; in many other ways, it is not. American veterans of New Guinea recognized this disconnect decades ago: “One of the permanent effects of this war . . . will be a decline in movies with the South Seas Island settings. American soldiers who have returned from the South-west Pacific will be unable to refrain from laughing out loud at the alluring women and romantic scenery. . . . Dorothy Lamour and her luscious colleagues [might] want to get out before it is too late.”6

Like the other unique environments across the globe, the jungle environment has distinct characteristics and qualities that deserve dedicated attention and study. It is worth the time to understand what precisely a jungle is and is not, and how that frames the operational environment in terms of historical case study and consideration of future military operations. The Earth has nine different biomes, which help us categorize the various regions of the planet based on climate, geography and forms of life. The tropical rainforest is one of these nine. It is only found at specific latitudes, and it makes up about 6 percent of the earth’s terrestrial surface.7 Like all forms of rainforest, the tropical rainforest consists of four distinct layers: emergent, canopy, understory and floor layer.8 Due to their proximity to the equator, constant sunlight produces prolific vegetative growth and humidity, which allows for incredible quantities of rainfall throughout the year, between 80 and 400 inches, depending on the specific location.9

The term jungle is often used interchangeably with tropical rainforest in conversation. However, a jungle is more akin to a state of condition, not a unique or distinguishable biome. Generally found within tropical rainforest biomes, a jungle occurs when enough breaks in the canopy layer admit sufficient sunlight to the understory and floor layers to promote excessive vegetative growth. Such a condition is often further categorized into primary, secondary and coastal jungles. The differentiating factor is the degree of sunlight and, therefore, amount of undergrowth that develops. When some, but not enough, sunlight breaks the canopy layer, the floor layer will start to grow more, but generally, the heat becomes trapped, forcing the humidity and moisture levels to skyrocket. The result is a thick, soup-like air with incredibly soft and wet ground. A secondary jungle exists where, through natural or manufactured means, more sunlight breaks the canopy layer, allowing the undergrowth to grow unchecked, resulting in the stereotypical jungle environment that most people imagine.10

Given a basic understanding of the difference between jungle types and the tropical rainforest biome, this monograph will endeavor to distinguish between each moving forward. It is essential to understand how the environment influences events and decisionmaking. Regardless of whether a person finds themselves trudging through peanut butter-thick mud in a primary jungle, battling “wait-a-minute” vines in the secondary jungle, or wading through coastal mangrove swamps where the rainforest meets the salty coastline, there are some consistent features of the jungle that transcend their location on the planet: sound, light and disease.11

These characteristics have profound tactical effects with operational and even strategic implications. Noise discipline is a common refrain small unit leaders emphasize with the modern Soldier. As a means of protection and a component of surprise, maintaining a degree of silence during operations often contributes to success in combat. When combined with the physical dimensions of the jungle, such as tree density or lack of navigable routes between points, two groups of human beings moving through a jungle can often operate within feet of one other and not know it. During the New Guinea Campaign, it was not just the sound of the enemy unit that Soldiers had to contend with, but also the sound of the jungle itself. Though wildlife by common standards was scarce, the jungle was undoubtedly alive with insects, amphibious creatures such as crabs, and water.

In the pitch darkness, Soldiers would often be unable to distinguish the sounds of the jungle itself from that of the Japanese: “That night, the damn land crabs would get in these cans, and it sounds like the whole damn Japanese Army is approaching.”12 This combination of noise and geographical density would become the driving force behind the ambush and the primacy of defensive tactics over offensive action. The Australian and Japanese battles along the Kokoda trail, as we will explore, are one example of how small-scale tactical actions shape the experience of the Soldier on the ground and the operational approach of the strategic planner: “In the South Pacific, the moment of truth might well have been found in a submachine-gun battle at ten yards, followed by a bayonet attack.”13

The words jungle and disease go hand in hand, and it should be no surprise that disease outpaced enemy fire as the primary source of casualties throughout the Pacific War. Indeed, the “greatest cause of noneffectivness of military personnel in Jungle Operations” was malaria.14 Across the entire Southwest Pacific Area, disease accounted for 83 percent of all casualties.15 In their review of medical health concerning New Guinea’s geography, Eugene Palka and Francis Galgano note that the low-lying lands around coastlines proved optimal breeding grounds for disease vectors such as flies, mosquitoes and rats.16 The lack of infrastructure across the island and incessant rainfall eliminated an army’s ability to rotate stricken Soldiers out of a disease hotspot or to push clean water and medical supplies forward. The American and Australian armies would go to incredible lengths throughout the New Guinea Campaign to mitigate the effects of disease, though much of their success required time, adaption and trial. The allied efforts to mitigate and prevent disease-based casualties would often directly influence leadership decisions on the campaign’s conduct.

The Australians Evolve

The Australian experience throughout the New Guinea Campaign highlights the inevitable link between tactical action and strategic objectives. The modern discourse of military operations seems to follow two trends. In popular history, there is a hyper-focus on the tactical level of warfare, fetishizing the heroic exploits of the soldier with little attention given to the operational and strategic levels of war. In the academic realm, the opposite seems to be the rule; the tactical level of warfare is often of secondary focus to the higher realms of war and, therefore, discarded from serious discussion. The Australian experience throughout New Guinea demonstrates that leaders and organizations generate success on the battlefield and beyond by understanding that combat represents a system. In this instance, the Australians placed the individual soldier at the crux of their thinking. Through their emphasis on getting small unit tactics in the jungle right, the Australians effectively showed the necessity of an adequately trained soldier and the ability for the organization to, in current doctrinal terms, prolong its “ability to employ combat power anywhere for protracted periods” (endurance) and delay the “point [at] which a force no longer can continue its form of operations, offense or defense” (culmination).17

Through multiple iterations in similar yet wildly different theaters, such as Malaya and Ceylon, the Australians documented numerous points that demanded a change in behavior across echelons. For instance, during preparations for combat on the island of Timor, one battalion commander recognized the apparent discrepancy between what the Australian soldier was wearing and the foliage color of their surrounding environment. Australian soldiers fighting in Malaya and across islands such as Timor were fighting in the same uniforms as their counterparts in North Africa. Camouflage and appropriately colored uniforms, as simple as it sounds, offered an essential yet fundamental change in combat at the tactical level. Bottom-up feedback, such as uniform color, demonstrated that, at least at the tactical level, the Australians immediately recognized the emergent behavior of the system they were now a part of. Malaya, Timor, and, unfortunately, the early parts of Kokoda, each represented multiple iterations of inquiry. Sadly, in the case of changing uniform color, it would take nearly ten months of combat between identifying a problem and implementing a solution.18

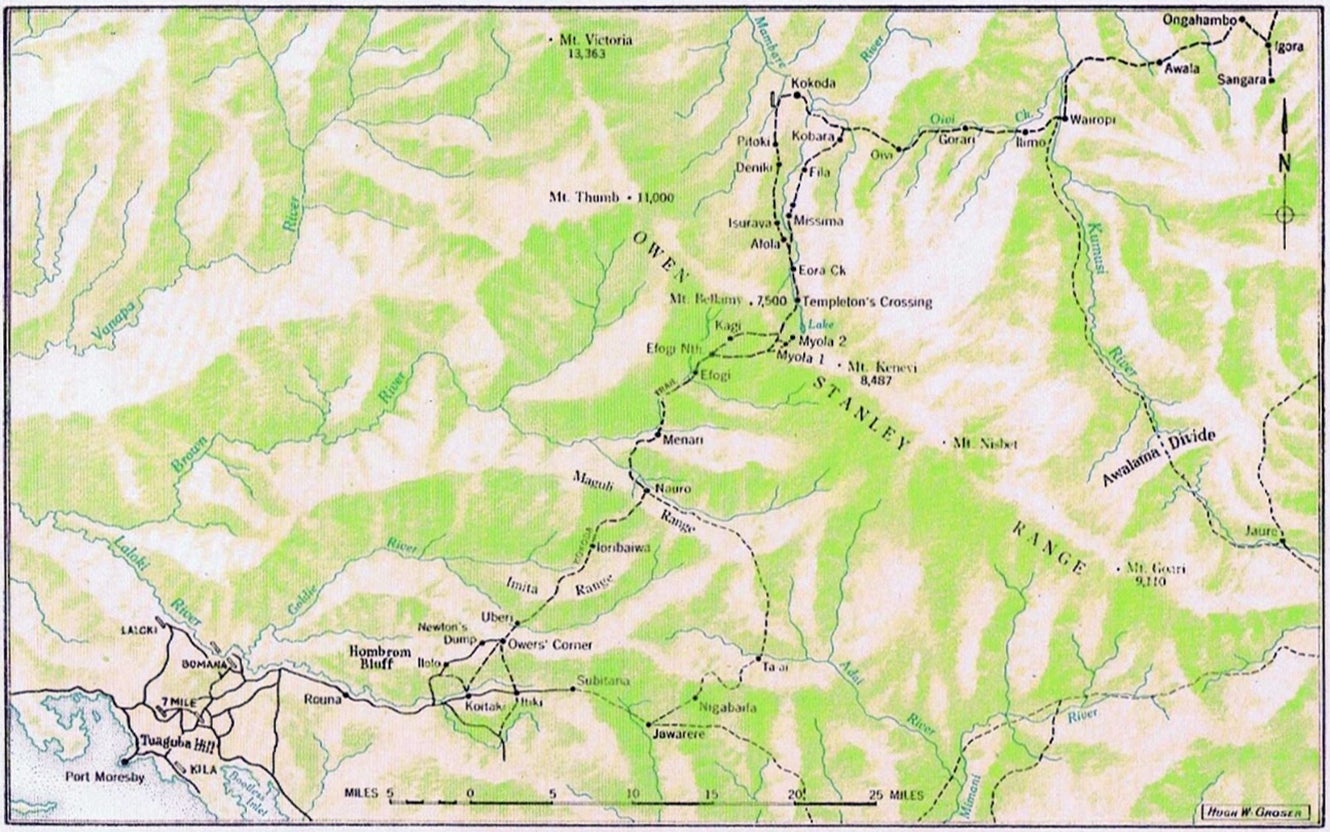

Figure 2: Key Locations Along the Southwest End of New Guinea21

The Owen Stanley mountain range (Figures 1 and 2) is the predominant terrain feature on the island of New Guinea. Reaching a peak elevation of over 13,000 feet, the range spans 200 miles from east to west, cutting the island in half. If you were to fly past it, you would notice razor-sharp ridgelines and deep canyons that can span miles. Weather patterns are dramatic, with the mountain range erupting out of the coastline, going from sea level to over 8,000 feet. Rain is constant, and mud is ever-present. Hypothermia was a constant threat at elevation, and it would not be uncommon for soldiers to cover 2,000 feet or more in elevation gain or loss on one of the many tracks traversing this alien landscape.19 This was the setting for the Kokoda trail campaign of 1942, and it became the proving ground where the AIF evolved its approach to jungle warfare.

Although Australians entered World War II in 1939, the war did not come to Australia’s borders until the end of 1941. Through the early war years, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his Australian counterpart, John Curtain, had differing perspectives in prioritizing combat-ready Australian forces to defend Southwest Pacific sea lanes. Churchill would see his demands for more Australians supporting the Middle Eastern theater satisfied, which meant that Prime Minister Curtain had to establish defensive garrisons with whatever manpower was leftover.20 The early months of 1942 saw the incredible advance of Imperial Japan across the Southwest Pacific, taking Rabaul on 23 January, Singapore on 15 February and both Salamaua and Lea on New Guinea on 7 March.

By July 1942, the Japanese controlled the coastal towns of Buna and Gona on the north coast, opposite Port Moresby. They immediately set their eyes on capturing this southern port town, thus eliminating the last allied stronghold between the Japanese advance and the Australian coast. However, they had a problem. Although the Japanese Navy scored a tactical victory at Coral Sea that May, it would prove an operational defeat as it prevented them from completing their amphibious landing on the southern coast of New Guinea. Their only option was to cross the Owen Stanleys via a small, roughly 30-mile-long dirt track: Kokoda (Figures 2 and 3).

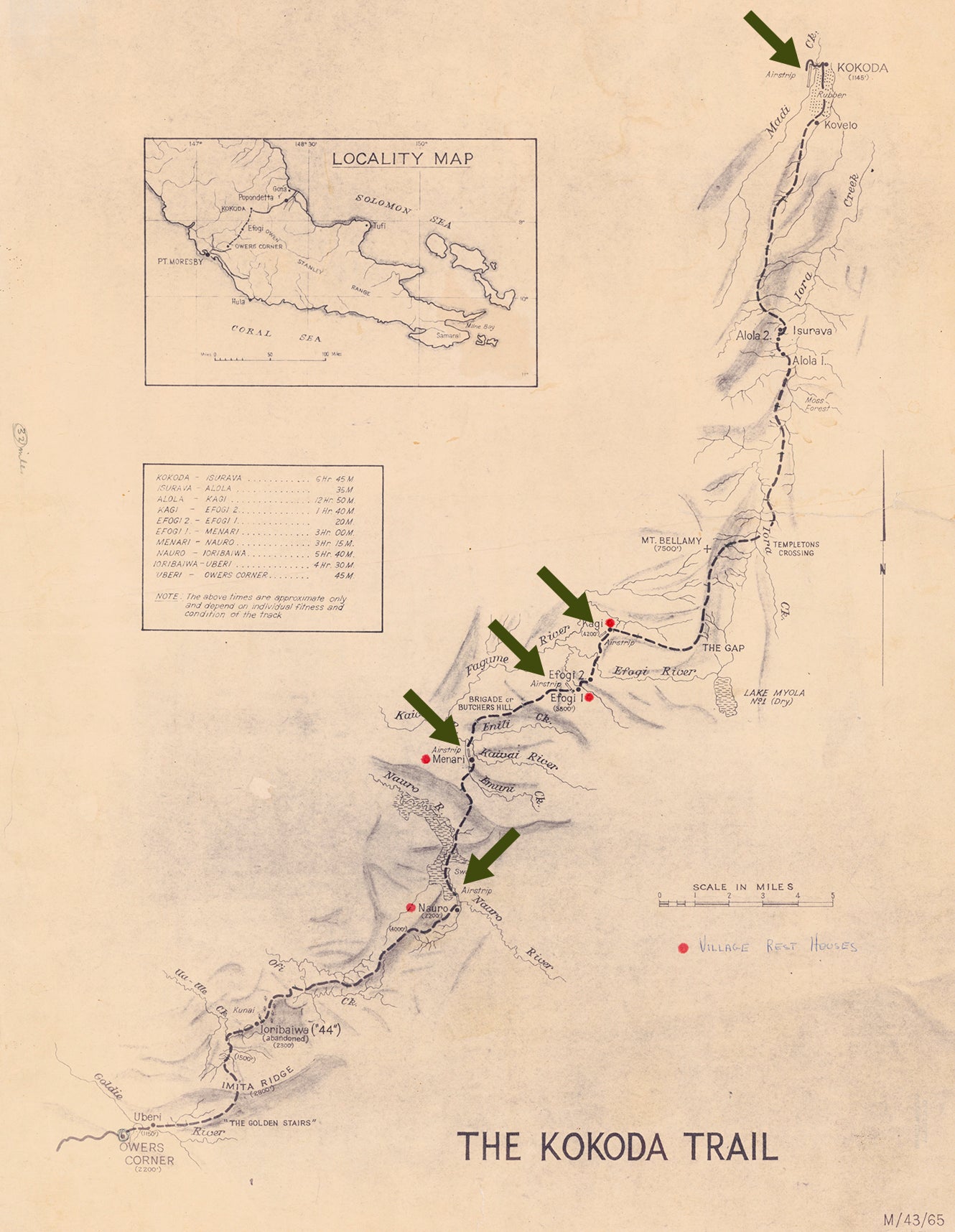

Figure 3: The Kokoda Trail from Port Moresby to Kokoda25

At the end of July 1942, the Japanese 144th Infantry Regiment and 15th Independent Engineer Regiment, reinforced with some 11,500 Imperial Army and construction soldiers, had orders to take Port Moresby by land. Collectively known as the South Seas Detachment (SSD), this Japanese force had little to no understanding of their enemy on the other side of the Owen Stanleys nor of the savage landscape they were about to plunge themselves into. John McManus highlights the Japanese ignorance of the operating environment: “So ignorant were the Japanese of Kokoda’s realities that they brought packhorses who could not hope to survive such privation.”22 The Japanese assault along the Kokoda trail is a grueling tale in and of itself and worth studying on its own. However, that is beyond the scope of this monograph.

Ultimately, the Japanese, like all soldiers in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), were beset by the jungle, disease, hunger and the elements. The lack of logistical infrastructure and overextension of their operational reach are commonly considered the chief contributors to the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA’s) failure to achieve its objectives across the South Pacific. Eric Bergerud argues that the allied landings on Guadalcanal effectively guaranteed defeat for the Japanese. By driving a wedge between the already contentious Army-Navy rivalry, the Guadalcanal Campaign forced the Imperial General Headquarters to split and then redirect what forces were available for New Guinea to Guadalcanal, eliminating any chance for Japanese success at either location. “Had they turned everything they had against either Guadalcanal or Port Moresby, a victory at either would have been very possible. As it was, they stumbled from one half-measure to another.”23 The South Seas Detachment got no closer than 26 miles to Port Moresby through August, and with the failed amphibious landings at Milne Bay, Imperial Japanese leadership decided to divert forces to reinforce the effort against the allied invasion of Guadalcanal. Major General Tomitaro Horri and his SSD were ordered to retreat.24

Jamshid Gharajedaghi notes: “Iteration is the key to understanding complexity.”26 For the Australians, the Kokoda campaign marked a turning point in their understanding, adaptation and competence in the jungle environment. Although still slow to adapt to every instance, e.g., uniform color, their army’s pace of experimentation increased toward June 1942. In preparation for operations across New Guinea, the Army’s 7th Division circulated numerous short reports and pamphlets collected from units across the operational area, including Army Training Memoranda 10 and First Army Training Instruction No. 3: Jungle Warfare. Tactical-level leaders attempted to permeate lessons learned from fighting in the Malayan jungles through these documents.27 Coupled with the early development of jungle-specific training centers across Australia, this marked one of the early iterations by the Australians to update their training methods and doctrine concurrently. However, they did not achieve the desired effect.

When units such as the 7th Division departed for Papua New Guinea, the overriding sentiment was that they were educated on the jungle terrain, had practiced relevant tactics and had conducted rigorous training exercises in Queensland. However, Adrian Threlfall notes that the division, now six months removed from the deserts of Syria, had never experienced the actual terrain of Papua New Guinea. The 7th Division expected weeks of rigorous training in Australia to bolster their robust experience fighting in the desert. Clearly, “The Australian Army was preparing for the sort of war it had already experienced and therefore knew how to fight.”28

By mid-September 1942, the Japanese had beaten Australian defenses along the Kokoda trail as far south as they would get and found themselves halted at Ioribaiwa Ridge. Fortuitous circumstances at Guadalcanal and overextended supply lines forced Imperial Japanese leadership to reprioritize supplies and reinforcements elsewhere. Allied planning for a counterattack to retake the Owen Stanleys and Kokoda began in earnest in late September. The summer Japanese offensive, driving Australian Army forces and militia back toward Port Moresby, finally began to drive home some of the observations tactical leaders had been advocating across the Australian Army for nearly a year. On 20 September 1942, Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell, commander of I Australian Corps and the New Guinea Force, wrote his assessment to Australian Army Headquarters:

The main reasons for the success of the Japanese in forcing the Owen Stanley Range and advancing on Moresby are as follows. . . . Higher standard of training of enemy in jungle warfare. Our men have been bewildered and are still dominated by their environment. . . . [T]here are two important factors to be stressed: The wastage of personnel from battle casualties and physical exhaustion is extremely high. This demands greater . . . reserves of fresh units to replace those temporarily deplored in number or otherwise battle weary. . . . Training as known in Queensland bears no relation to jungle conditions. . . . It is essential that troops get into actual jungle and learn to master its difficulties of tactics, movement, and control.29

Despite these reports, Australian Land Headquarters (LHQ) continued to suffer delays in adopting the essential materiel goods for the soldiers on the ground, as exemplified by Brigadier Kenneth Eather’s 25th Infantry Brigade digging fighting positions with helmets and bayonets along Imita Ridge because no one had shovels.30 Brigadier Arnold Potts, commanding the 21st Brigade, also wrote to Headquarters that soldiers coming to New Guinea must be trained in a similar environment and on the unique tactics relevant to warfare on the island.31 Rowell and Potts’ letters highlight the Australian’s evolving understanding of the character of warfare in New Guinea. If allied forces were to successfully maneuver up and over the Kokoda trail and fight their way through the Gap at Templeton’s Crossing—a five-mile-wide broken saddle elevated 7,500 feet above sea level where there is only enough space for a single man abreast to maneuver—then endurance was the watchword of the day.32

Modern U.S. Army doctrine, such as ADP 3-0, exclusively uses the term endurance in the context of extending military operations to promote operational reach and to delay the culmination of the organization. While such a framework is not necessarily wrong, the Australian experience during the Kokoda trail campaign demonstrates the genuine necessity to account for the literal human endurance of the soldiers on the ground. The jungle environment in New Guinea equalized the technological and conceptual planning advantage the SWPA command system had over the Japanese. For instance, the sustainment infrastructure the allies had over the Japanese was invaluable. By this point in the war, the Japanese had extended their forces to the absolute limit. They could not further extend operational reach to provide logistical support to IJA forces simultaneously in places like New Guinea and Guadalcanal. “The Japanese . . . had never been able to establish an air bridge. . . . Historian Karl James notes that as the campaign progressed and the Japanese supply lines were hopelessly overextended, ‘more men succumbed to tropical diseases and exhaustion due to starvation and malnutrition.’”33 In the most extreme instance, the IJA approach of isolated, unsupported forces fighting to the last drove Imperial Japanese soldiers to cannibalism. James Carafano and others comment on how cannibalism was likely a natural result of the depths of starvation faced by the IJA soldiers fighting across the New Guinea jungles.34

When Generals Rowell and Potts identified the need to train the individual in the specific jungle environment, they recognized its unique effects on their ability to mitigate organizational culmination. If the squad, section and platoon cannot physically maneuver on the ground, the brigade and army cannot coordinate tactical action to achieve effects. In other words, Rowell recognized an unsustainable feedback loop: New Guinea itself drained manpower at an accelerated rate, and this rate of attrition increased exponentially with inadequately trained reinforcements, thus requiring commanders to increase the rate at which they needed reinforcements, forcing LHQ to cut training to meet demand, thereby only accelerating the rate of attrition grinding operations to a halt.

Since February 1941, LHQ has operated the small Guerilla Warfare School at Foster, Victoria, in Australia. By October 1942, units began establishing internal training programs and centers to break this feedback loop and to fill the gap left by the lack of a centralized jungle training program from LHQ. These training programs included the Jungle Warfare Training Center in Lowanaa along the New South Wales Coastline. Ultimately, after the early iterations of centralized training facilities at Lowanna and the Guerilla Warfare School in Foster, LHQ established the Jungle Training Center at Canungra in Queensland, Australia, in early December 1942. The Jungle Training Center consisted of multiple small unit tactical schools and primarily focused on training squads and platoons to fight in the jungles of New Guinea, with 28 additional days of entry training. Within its first year, the Jungle Training Center built a capacity to train 6,000 replacements at a time.35 This training center at Canungra is still in operation and has since evolved into the primary land warfare training center for the Australian Army.

Soldier and small unit training centers were only one part of the solution. The Australian Army still had to reconcile the disparate efforts to produce a cohesive and common training doctrine to fight in New Guinea. Through this point in the war, units continued to exchange short reports from Malaya and to rely on unit-level training memoranda. Between 1944 and 1945, Lieutenant General Stanley Savige, commander of the II Australian Corps, produced a comprehensive internal jungle doctrine that embodied the pinnacle of unit-driven efforts to educate its soldiers and instill commonality in how small units fight in the jungle.36 The document resulted from Australian Army forces capturing the disparate collection of lessons learned, reports and publications into a single doctrine. Recognizing this shortfall, LHQ leaned heavily on two forms of doctrinal development: soldiers with first-hand experience becoming trainers at Canungra and small teams circulating the theater to observe and record best practices and the experience of those in the fight.37 In the meantime, the primary focus of Canungra and units in the field was to produce the most physically fit and well-adapted soldier possible to withstand the rigors of Papua New Guinea. Indeed, Lt. Gen. Savige’s top three priorities for his Corps were to keep the men fit, well-fed and clean.38

This effort would understandably take time to produce a comprehensive written product. That said, the Australian effort to develop and codify jungle training literature for the soldier exemplifies the iterative process required to successfully integrate DOTMLPF-P change from a training perspective. Indeed, the U.S. Joint Staff associates training considerations with anticipating requirements and missions: “The training . . . consideration pertaining to training of individuals, units, and staffs . . . to prepare joint forces or joint staffs to respond to . . . requirements considered necessary . . . to execute their assigned or anticipated missions.”39 This is precisely what the Australians fighting in New Guinea did.

The Americans Adapt

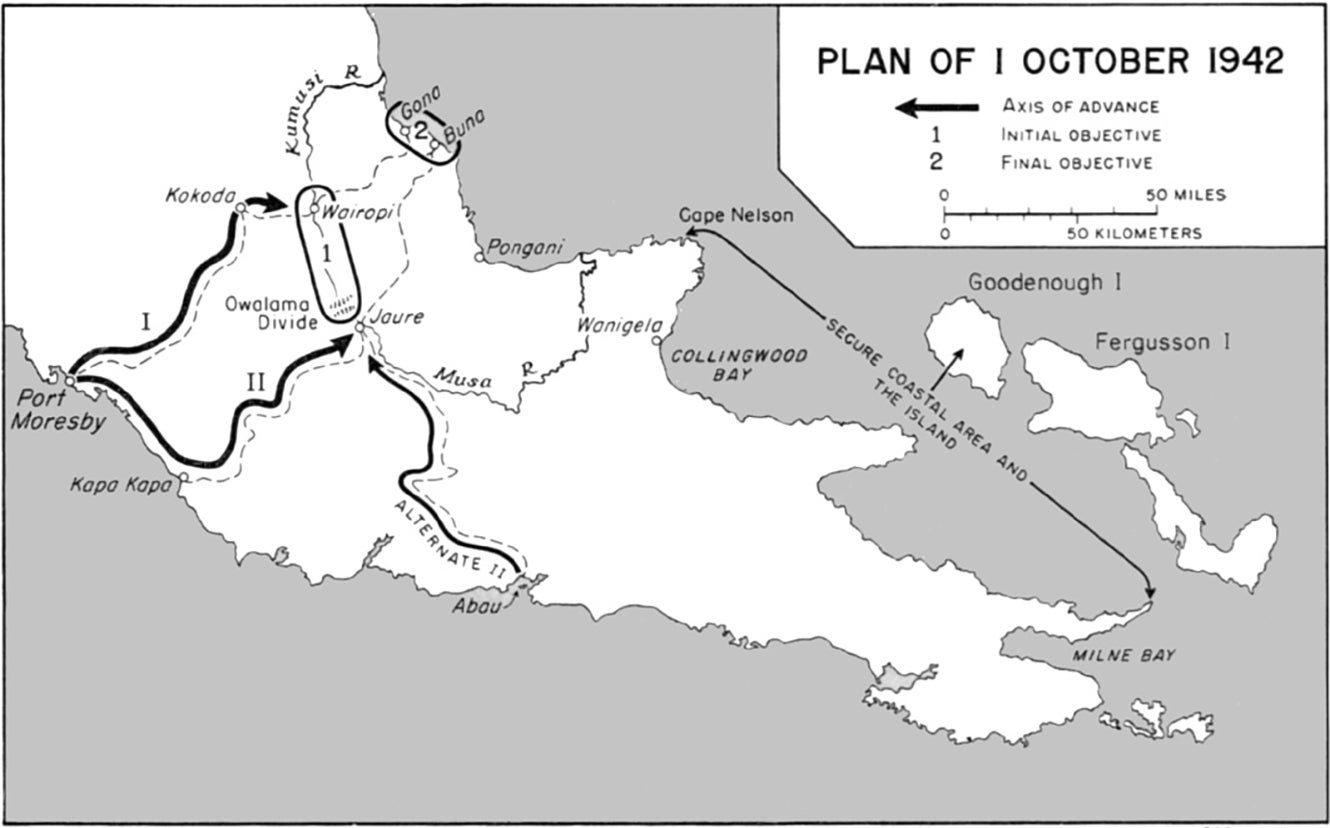

The Australian-heavy Kokoda trail campaign was driven by General MacArthur’s long-time goal of controlling the ports of Buna and Gona on the island’s northeast end. He directed the Australian 7th Division to cross the Owen Stanleys and spearhead the attack to achieve this goal, while the American 32d Division would secure the 7th Division’s right flank and attack Buna. The full story of the 32d Infantry Division’s trek across the Owen Stanleys is harrowing, dramatic, and, again, beyond the scope of this monograph. That said, the 42-day journey of the 2d Battalion, 126th Infantry Regiment along the Kapa Kapa track epitomized early American arrogance of the New Guinea landscape. After refusing Australian advice against using it, MacArthur would eventually tell Lieutenant General Eichelberger, “Take Buna or do not come back alive!”40

Through no fault of the Soldiers, the entire state of the 32d Division encapsulated American ignorance of the environment as they entered New Guinea. Beyond anything the Americans had experienced in their history, those jungles took advantage of their lack of regional knowledge and experience. Although New Guinea was a scale of difficulty beyond what the Australians had encountered in Malaya and during the Japanese assault toward Port Moresby along the Kokoda trail, New Guinea was novel for the first American forces to arrive.42 Upon arrival to Jaure (see Figure 4), the state of the 2d Battalion would lead MacArthur to abandon any remaining notion that an overland route to supply the northeast coast was viable. Air supply, and therefore air bases (in addition to sea bases), would dictate success for MacArthur’s forces across the SWPA.

Figure 4: Allied Plan of Movement Across the Owen Stanleys41

The combination of inadequate training and poor intelligence led to a stalemate between Japanese Imperial forces—including those of General Horri, who had recently withdrawn along the Kokoda trail—and the 32d Infantry Division around the perimeter of Buna, much to MacArthur’s frustration. To end this stalemate, MacArthur ordered Eichelberger to take charge of the effort to capture the village with his famous ultimatum. Eichelberger would waste no time inserting himself into the middle of the fray. He ordered medical assessments for every man, met with Soldiers and leadership at echelon and personally toured what he could find of the front lines.43 Eichelberger identified that “two things were imperatively necessary: reorganization of the troops and immediate improvement of supply.”44 Ranking officers were relieved, competent corps staff officers were given combat command on the spot and sustainment was made the priority for the corps staff.

In early December 1942, Eichelberger did the only thing he could without properly trained jungle Soldiers: He demonstrated visible leadership. He walked for hours in knee-deep water from one flank to the other, led small units against Japanese bunkers and openly wore glossed rank on his uniform on the front lines. “How else would those sick and cast-down soldiers have known their commander was in there with them?”45 In addition to being actually present, Eichelberger recognized the immediate need to condition his Soldiers to operate in the jungle. Since the Soldiers of the 32d Division did not have the benefit of the Australian training infrastructure, Eichelberger trained through operations. He mandated patrols simply to improve his unit’s capability in the environment. An incredulous observer from the War Department noted: “Orders were issued that each company for TRAINING PURPOSES would send out one patrol commanded by an officer each night.”46

Despite a hellacious first encounter with the jungles of New Guinea and an inept intelligence estimate, courtesy of the SWPA G2, Brigadier General Charles Willoughby, Robert Eichelberger’s I Corps, coupled with the Australian 7th Division, won the United States its first ground battle of World War II by 14 December 1942. It would be unfair to the Soldiers across I Corps to say that Eichelberger single-handedly saved the allied assault to seize Buna. Nevertheless, his leadership undoubtedly instituted a marked change in those Soldiers’ behavior, morale and discipline, mired as they had previously been in the stalemate outside Bona. By reviewing MacArthur’s reports, he recognized the nature of New Guinea’s environment and the degree to which Americans were unprepared for it before he arrived on the island.47 For these reasons, Eichelberger understood that discipline was the only reasonable mitigation against the effects of the jungle.

Additionally, in placing himself on the front line, engaging enemy bunkers and participating in combat himself, Eichelberger was able to gain an appreciation for the nature of combat in New Guinea that would take MacArthur and his staff months, if not years, to understand. For instance, Japanese bunkers built from coconut trees proved impenetrable to the munitions that the 32d had on hand. Nevertheless, MacArthur’s staff continuously hesitated to commit the artillery General Harding requested to defeat them. The staff assumed that they would be unable to insert the artillery into the jungle and that Harding’s forces would be unable to maneuver it inside the vegetation. General George Kenny, commander of the SWPA’s allied Air Forces, summed up the staff’s initial sentiment toward artillery in the jungle: “The artillery in this theater flies.”48

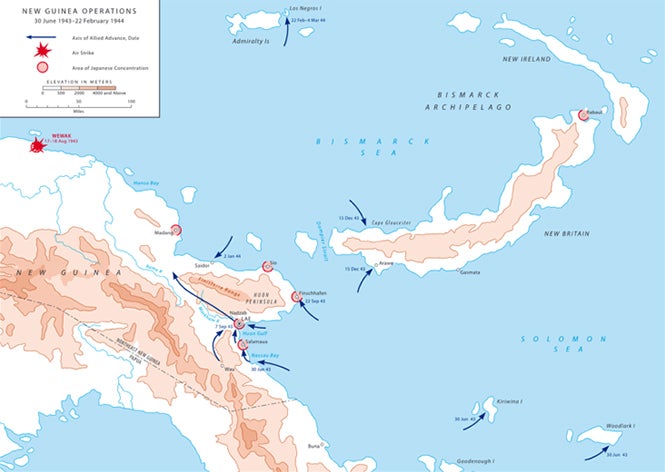

General MacArthur’s delusions about World War I style maneuvers aside, he did understand the organization requirements necessary to coordinate operational effects across New Guinea and the greater SWPA.49 By March 1943, the allies had defeated the Japanese threat to the Australian mainland with victories at Buna, Gona and Guadalcanal. Operationally, eyes remained on the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul, its capture, and the drive north toward Tokyo. On 29 March 1943, the allied Joint Chiefs approved a two-pronged operation aimed to do just this: Operation Cartwheel.50 For months, MacArthur had his eyes set on Rabaul, but he clearly understood the degree to which the Japanese held it.51

Figure 5: Allied Amphibious Movements, June 1943 to February 194452

Even from the early days of combat on New Guinea, MacArthur and his staff understood that to eject the Japanese from the islands across the SWPA and to isolate Rabaul, allied forces would require substantial bases and hubs from which to operate. The Kokoda trail campaign, as an example, necessitated control of Kokoda and the primitive airfields (see Figure 6) across the middle of the Owen Stanleys to support combat operations via airdrop. The concept extends to the whole of the SWPA. The jungle environment forced combatants to be in extreme proximity to Japanese defensive fortifications while significantly reducing the effectiveness of massed fire support. The munitions on hand during the early battles of New Guinea could not penetrate Japanese defensive fortifications. Soldiers on the ground recognized the need for more significant artillery fire. However, SWPA planners simply assumed that it was impractical to try to get artillery inland and that airpower could more than make up for it.53 Thus, the only way to sustain tactical action and operational coordination was to navigate around the jungle and mountainous terrain itself. “Every Allied operation depended on an extensive logistics infrastructure . . . through the ships that were the umbilical cord between the advance base and the staging areas.”54

Figure 6: Airstrips Along the Kokoda Trail55

When MacArthur and the SWPA staff received the final Operation Cartwheel directive, they initiated a modified version of plans that would direct his forces to address this issue. This plan was known as ELKTON III. Through its revisions, the ELKTON plans all prioritized control of airdromes and sustainment hubs to support operations against Rabaul.56 Starting at the Buna and Gona coastline, MacArthur’s forces would conduct a series of amphibious landings northwest along the coastline of New Guinea to secure existing basing areas from the Japanese or areas suitable for his engineers to build new ones.

After the action at Kokoda, Guadalcanal, Buna and Gona, MacArthur began to understand the peril of attempting to thoroughly sweep the Japanese off an island. Instead, he aimed to bypass as much jungle as possible and, in turn, to avoid unnecessary contact with entrenched Japanese to isolate crucial airfields and ports.57 The evolution of allied planning centered on the concept codified in modern doctrine known as basing. By shifting allied operations from an enemy focus to a terrain-based focus, allied forces planned to bypass Japanese strong points and to focus efforts on those points suitable for occupying or constructing forward bases, primarily to extend the operational reach of their ground, air and maritime forces. Given the limits of technology at the time, specifically aircraft fuel capacity and range, operations in New Guinea from the middle of 1943 to early 1944 required the Army to conduct multiple amphibious operations to control intermediate coastal basing locations to secure subsequent staging bases. The plan emphasized the first imperative of multidomain operations: “See yourself, see the enemy, and understand the operational environment.”58 The environment dictated ELKTON III’s planning and intention.

Without this lily pad method of hopping along the coastline, the allies could never have extended their operational reach to Rabaul with enough combat power to achieve the desired objective. The initial assaults on Kiriwina and Woodlark to the east of Buna highlight the potentiality of insufficient basing. General Walter Kreuger and the 6th Army understood that the Fifth Air Force “would not be capable of providing fighter protection to his troops being convoyed to the islands because planes from his nearest airfield would not have enough fuel to linger off the ships.”59 Fortunately for the Regimental Combat Teams, Marines and engineers, the Japanese they expected to encounter during their nighttime landing likely relocated to attack Admiral Halsey’s forces landing on New Georgia island.60

Not only did the environment influence what the allies would do militarily, but it also influenced how they would do it. MacArthur’s forces remained under-resourced as the war moved toward 1944 to execute continuous, full-scale offensive operations. Additionally, his staff and commanders had to solve the problem of how to get increasing numbers of combat troops across an increasingly separated geographical area via ship-to-shore means. Not only was the Navy responsible for its operations in support of Operation Cartwheel, but, naturally, they also had to manage blue water transport for all allied forces across all four Pacific combat areas. There simply were not enough transport vessels to meet MacArthur’s needs. The massive Landing Ship, Tank (LST), and Landing Ship, Infantry (LSI), could not land under fire or navigate the innumerable uncharted coral reefs that dotted New Guinea and surrounding island coastlines. The allies needed smaller, faster, protected platforms to move troops to shore and between landing sites.

MacArthur’s answer was the Engineer Special Brigade (ESB). The ESBs were designed to rapidly move men and equipment from ship to shore or shore to shore. A single ESB comprised of 7,300 Soldiers, 600 Land Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVPs), and Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM). Crucially, they also could “move them off the beach, assist in supplying them, and provide perimeter defense.”61 Despite performing beyond expectation, some of the heavy transport vessels also used by the ESBs were still relatively large and slow, and they were easy targets for hardened Japanese defensive positions and air forces. To mitigate this risk and to enable MacArthur’s coastal basing approach, the ESBs equipped their LCMs and LCVPs with rockets and heavy machine guns to create shore-based fire support batteries.62 MacArthur’s use and restructuring of his ESB and various landing craft exemplify the DOTMLPF-P elements of organization and materiel with respect to how he considered their capabilities and adapted them to meet the mission requirements.63

Much as the Australians did during their trial-by-fire experience inland through New Guinea and the Owen Stanley mountains, MacArthur recognized the need to dedicate specific organizations to train for the specific environment. When SWPA was assigned the 7th Amphibious Force from the Navy in 1943, MacArthur immediately directed its commander to establish an amphibious operations training program with his 2d ESB. This four-week program was built for units from battalion and above and purposefully worked to synchronize multidomain efforts between ground, air and naval units from training to pre-execution rehearsal.64

Tomorrow’s New Guinea

Wars have the habit of taking place where they are unexpected. Despite the alarms raised by American and British intelligence services, Europe, and to an extent Ukraine itself, the world was somehow caught by surprise when Russian forces crossed the Ukrainian border on 24 February 2022.65 Despite hundreds of thousands of troops amassed on the border during the preceding months, not to mention a previous military invasion six years prior, the global community thought a conventional invasion beyond the pale in 2022.66

Through the late 1930s and early 1940s, as World War II broke out and Germany gained initial victories across Holland and France, Australia and the United States continued diplomatic efforts to keep Japan from furthering aggressions across the Pacific.67 The famous American interwar plans for conflict with Japan, known as Plan Orange, chiefly consisted of naval movements across the Western Pacific, engaging in decisive battles with the Japanese naval force, relieving pressure on the Philippines and, ultimately, blockading the Japanese mainland.68

In support of the British efforts against Germany, the 2nd Australian Imperial Force deployed its crack troops to the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean theaters. With the surrender of American and Filipino forces in the spring of 1942, there was nothing left in Imperial Japan’s way to achieve one of its strategic objectives: cutting the Australian continent off from its Western allies. It comes as little surprise to those of us with hindsight that both the Americans and the Australians found themselves flatfooted as Japan raced across the Pacific theater, absorbing island after island, coming to a rest at Australia’s doorstep. James Carafano sets the mood well: “Before this point in the war, a Japanese threat to the Australian homeland was no part of anybody’s war plan. When the warring powers started to think about fighting for Australia, they were starting from scratch. Certainly, nobody envisioned fighting a protracted jungle war on the country’s doorstep in Papua New Guinea.”69

Where, then, will tomorrow’s New Guinea Campaign take place? Not only is that an impossible question to answer, but it is also an unhelpful one to ask. However, it highlights an essential point that contemporary discussion on future conflict often loses sight of. Preparedness cannot lose out to anticipation. By this, I mean that contemporary militaries cannot afford to forego preparation in unique environments simply because planners and thinkers do not anticipate significant conflict to occur in those environments. As discussed throughout this monograph, it took both the Australians and Americans nearly two years to begin meaningful adaptations to fight in the jungles, mountains and coasts of New Guinea, at an incredible cost, mainly because no one expected a prolonged conflict in the region. Today, commentators have assumed that the next major Pacific conflict will occur in the South China Sea or Taiwan. Instead, we should ask: Where do we not think that conflict is likely to break out?

In recent years, conversations about the potential conflict between China and the United States have taken center stage. Think tanks, scholars and government agencies have poured countless amounts of time and money into considering what such a conflict would look like, where it may take place and what the results might be. Chief among these focus points is a potential military invasion by the People’s Republic of China into Taiwan and naval engagements across the South China Sea, in places such as the Spratley Islands or Paracel Islands. China’s Anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) network in the region is robust and draws significant attention from planners and thinkers; penetrating this A2/AD capability has become one of two principle focal points to respond to increased Chinese aggression, while the other is an indirect soft-power approach.70

This conversation is also dominated by the subjects of technology and platforms: How can artificial intelligence enhance decisionmaking? Where do hypersonic munitions fit into our own A2/AD bubble? Who will get autonomous drone swarms operational first? What about the effects of limited nuclear strikes? These are all valid and consequential topics. Nevertheless, it appears that this conversation is unknowingly, yet rapidly, forgetting that combat is an inherently human endeavor—regardless of the methods, it will require human beings to operate on the ground. Are the days of small tactical units fighting yards apart from the enemy in the Owen Stanleys or coordinating operational amphibious shore-to-shore landings to seize key airbases dead and gone? The multitude of wargames and new warfighting concepts, coupled with China’s diplomatic behavior, offer clues to the Soldier’s role in a large-scale, multidomain conflict.

Cleo Paskal, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, makes a compelling case that modern behavior by the Chinese Communist Party closely mirrors that of Imperial Japan. During the interwar years, Imperial Japan leveraged its colonial territories across the Pacific to establish infrastructure, schools, postal services and ports in places like Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands. These facilities, built over the course of 30 years, would prove invaluable to Japan in its efforts to delay American intervention across the Pacific because they were built as dual-use facilities.71 “By the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 . . . it was already prepared and dug in across what is noted the FAS [Freely Associated States] and the Commonwealth of Northern Marianas.”72 The rapid expansion of Japanese forces across the Pacific, to include places like New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, was done with the express intent to isolate Australia from the United States and to prevent it from becoming a significant power-projection hub.

The parallels to contemporary Chinese behavior across the region are not hard to see. In July 2023, the Chinese signed a security cooperation agreement with the Solomon Islands. This agreement expanded upon existing infrastructure agreements and intended to boost policing and security cooperation between the two countries in the region.73 Coupling its extensive military buildup with information and influence activities across the region, the Chinese Communist Party seems to be seeking to expand the operational reach of its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and, at least for the time being, indirectly working to reduce American access to Australia and the region.

Modern operational concepts coming to the fore tap into similar principles leveraged by MacArthur and the SWPA during the New Guinea campaign in World War II. Considering modern ballistic missile technology and the advent of space and cyber domains, most military thinkers do not assume that ground-based direct combat will occur during a Pacific-based conflict; instead, subsurface warfare, long-range precision fires and attacks along the electromagnetic spectrum will be the tools of choice, according to organizations such as the Center for Strategic & International Studies and the RAND Corporation.74, 75

In September 2023, Andrew Krepinevich, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, published one of the most comprehensive and wide-ranging operational concepts offered to planners and military commanders seeking to deter Chinese aggression across the Western Pacific Theater of Operations: Archipelagic Defense 2.0.76 A complete analysis and study of his concept is well beyond the bounds of this monograph; however, the concept is one of the few studies, wargames, or reports by a third party that accounts for ground combat in a modern Pacific conflict.

Taking numerous pages from the Australians and Americans during the Pacific War, Archipelagic Defense 2.0 calls for a forward-defense basing structure across the First Island Chain. Rather than being forced to dislodge Chinese forces across a network of islands and bases in the Western Pacific akin to what MacArthur had to do against Japan, Krepinevich advocates for permanent, dispersed and hardened bases that are capable of projecting combat power across all domains and in conjunction with a breadth of coalition partners.77Archipelagic Defense 2.0 specifically accounts for ground forces’ advantage over air and maritime partners when navigating an A2/AD bubble. Krepinevich views dispersed maneuverable ground forces integral for operations such as sea denial across the island chains: “Recall that ground forces enjoy relative advantages over air and maritime forces in their ability to harden themselves and to exploit terrain. . . . Ground forces can also sustain operations over long periods.”78 The commander of U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC), General Charles Flynn, is bringing the theater army to the same conclusions: “A key vulnerability in the People’s Republic of China’s anti-access/area defense makes conventional land forces—U.S. Soldiers and Marines—the joint force’s asymmetric advantage in a theater named for two oceans. The A2/AD system was built to find and destroy large, fast-moving ships and planes and to disrupt space and cyber capabilities. It was not designed to track distributed groups of mobile land forces inside its protective bubble.”79

There is nothing on earth quite like the geography and environment of New Guinea, and its latitudinal position on the earth makes its climate, flora and fauna distinct from the majority of first and even many second island chain locations. However, some commonalities translate regardless. Taiwan, for example, though much smaller, has a tropical climate for much of the year and a volcanic mountain range, similar to the Owen Stanleys, that divides the island in two. Vietnam has similar monsoon seasons, which can bring precipitation levels that approach those of New Guinea, at nearly 12 inches per month.80

As the PLA continues its work to extend its influence south and west past the second island chain toward places like the Solomon Islands, Fiji and Papua New Guinea, and the United States does the same westward through the Marshal Islands, Philippines and Vietnam, it stands to reason that, should conflict occur, the legacy of the Pacific War against the Japanese across these same islands will be alive and well. An American-led coalition asked to conduct operations in and around these environments cannot be trapped into thinking Soldiers on the ground will have no significant role. As General Flynn and USARPAC point out, the ground force may be the most significant advantage against a high-tech and capable Chinese A2/AD bubble: “Interior lines provide options . . . to help hold positional advantage and physically control important terrain such as maritime chokepoints.”81 The inroads to establishing preexisting interior lines and basing could eventually become what Andrew Krepinevich calls “turtle defenses.” Much like the Japanese withstood the allied airpower advantage during the Pacific War, American ground forces would inflict heavy casualties on Chinese forces despite their regional advantage in the air and maritime domains.82

Conclusion

Of all the geographic land-based environments on the planet, the jungle is the most alive and interactive with those who operate within its boundaries. It is anything but neutral, and only those who specifically train for and adapt to its characteristics have any chance to succeed within its confines. The tropical rainforest, specifically the jungle, is unlike anything else on earth. Armies in conflict within the jungle must adapt to extreme weather, the high risk of disease, confined physical space and countless forms of flora and fauna. During the early years of World War II, western armies had little conception of what it would take to fight a ferocious enemy in such an environment.

The Australians failed to adapt learned desert norms and practices to the battlefields of New Guinea. They quickly realized that success in New Guinea depended upon the capacity of the individual soldier to simply survive in the environment. It was not until they made this realization that the Australians began to make progress in driving organizational success against the Japanese on Kokoda. Meanwhile, though they learned many of the same hard lessons as the Australians, the Americans had to consider the jungle’s effects on its operational approach across the entire SWPA. General MacArthur observed the effects of the environment on his forces during various land campaigns and began to adapt his force’s plans and organizational structure to the environment to mitigate its effects on allied operations. By the end of the campaign, the Australians and Americans understood that victory against the Japanese in the jungle environment was only possible through a systems approach of adaptation, learning and anticipation. Each force manifested this principle through elements of the modern DOTMLPF-P framework. Through this lens, their experience in New Guinea demonstrates to the 21st-century descendants that doctrine, organization, leadership and training are the bedrock that the future force can rely on.

Students and practitioners of conflict in the 21st century must do their utmost to avoid planning for the last battle of the last war. After two decades in the deserts and mountains of Iraq and Afghanistan, the American Army has some bad habits to break if it hopes to successfully pivot its attention to the Pacific per the nation’s National Security Strategy.83 Countless reports and studies in recent years point to the increasing likelihood of conflict with The People’s Republic of China somewhere in the Pacific theater, but all too often, these reports categorize such conflict as a naval and air fight.

History, through a study of New Guinea, demonstrates that large-scale combat in this region inevitably boils down to land forces competing to control key terrain. Indeed, the current stalemate in the Ukraine war, as of April 2024, is characterized by a defense in depth built on miles of World War I style trench works. New wars are likely to combine novel technologies with tried-and-true techniques. Therefore, despite how drastically yesterday’s Pacific battlefields have changed over the past 80 years, the foundations of jungle fighting will become the link between yesterday’s lessons and tomorrow’s conflicts.

★ ★ ★ ★

Major Karl Rauch is currently a student at the School of Advanced Military Studies and a recent graduate of the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, KS. He was born in Philadelphia, PA, and is an alumnus of the University of Vermont, where he received his BA in Political Science. His education includes MAs from Webster University and CGSC. His military education includes the Jungle Operations Training Course, Air Assault School and the Special Reaction Team Course. He has served in theaters ranging from Afghanistan to the Pacific. He is married to his wonderful wife and fellow army officer, Brigid. Major Rauch is currently on assignment to be a planner with the 25th Infantry Division in Hawaii.

- Barack Obama, “Remarks By President Obama to the Australian Parliament,” The White House, 17 November 2011.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, eds. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 173.

- Adrian Threlfall, Jungle Warriors: From Tobruk to Kokoda and Beyond (New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2014), 3.

- Map data ©2024 Google. Screen-shot created by the author via https://www.google.com/maps.

- J. P. Cross, Jungle Warfare (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 14.

- James Jay Carafano, Brutal War: Jungle Fighting in Papua New Guinea, 1942 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2021), 59.

- Karla Moeller, “Revealing the Rainforest,” Arizona State University Ask a Biologist, 24 July 2013.

- Heather Johnson, “Rainforest,” National Geographic Education, 16 May 2023.

- Johnson, “Rainforest.”

- Bryan Perrett, A History of Jungle Warfare: From the Earliest Days to the Battlefields of Vietnam (South Yorkshire, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Military, 2015), 7.

- Eric M. Bergerud, Touched with Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1997), 70.

- Bergerud, Touched with Fire, 72.

- Bergerud, Touched with Fire, 279.

- Command and General Staff School, Medical Problems in Jungle Warfare and the Pacific Area (Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Command and General Staff School, May 10, 1945), 5.

- Eugene Joseph Palka and Francis A. Galgano, Military Geography: From Peace to War (Boston, MA: McGraw Hill Custom Publishing, 2005), 63.

- Palka and Galgano, Military Geography: From Peace to War, 49.

- Headquarters, Department of the Army (HQDA), Operations, Field Manual (FM) 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Army Publishing Directorate, 2022), 2–10.

- Adrian Threlfall, Jungle Warriors: From Tobruk to Kokoda and Beyond (New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 2014), 42.

- James Jay Carafano, Brutal War: Jungle Fighting in Papua New Guinea, 1942 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2021), 55.

- Carafano, Brutal War, 12.

- Map data ©2024 Google. Screen-shot created by the author via https://www.google.com/maps.

- John C. McManus, Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943 (New York, NY: Caliber, 2019), 263.

- Bergerud, Touched with Fire, 140.

- McManus, Fire and Fortitude, 267.

- Drawing by Hugh W. Grosea in South-West Pacific Area - First Year: Kokoda to Wau, 1st ed., vol. V, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Series 1-Army (Campbell: The Australian War Memorial, 1959), 114.

- Jamshid Gharajedaghi, Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity a Platform for Designing Business Architecture (Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2011), 92.

- Adrian Threlfall, Jungle Warriors: From Tobruk to Kokoda and Beyond (New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 2014), 80.

- Threlfall, Jungle Warriors, 90.

- Dudley McCarthy, South-West Pacific Area - First Year: Kokoda to Wau, 1st ed., vol. V, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1-Army (Campbell: The Australian War Memorial, 1959), 243.

- McCarthy, South-West Pacific Area - First Year: Kokoda to Wau, 244.

- Threlfall, Jungle Warriors, 140.

- Samuel Milner, Victory in Papua, United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific, CMH Pub 5-4 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1989), 58.

- James Jay Carafano, Brutal War: Jungle Fighting in Papua New Guinea, 1942 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2021), 188.

- Carafano, Brutal War, 189.

- Threlfall, Jungle Warriors, 140–142.

- Stanley Savige, “Tactical Doctrine for Jungle Warfare,” (II Australia Corps, 1944).

- Threlfall, Jungle Warriors, 144.

- Savige, “Tactical Doctrine for Jungle Warfare,” 1.

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), Joint Capabilities and Integration Development System Manual (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2018), B-G-F-3.

- Charles Anderson, Papua, The Campaigns of World War II, CMH 72-7 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2019), 22.

- Drawing by C.F. Cornelius in Victory in Papua, United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific, CMH Pub 5-4 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1989), 58.

- McManus, Fire and Fortitude, 274.

- Robert Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1950), 24.

- Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, 25.

- Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, 29.

- McManus, Fire and Fortitude, 328.

- Eichelberger, Our Jungle Road to Tokyo, 11.

- Milner, Victory in Papua, 135.

- McManus, Fire and Fortitude, 331.

- McManus, Fire and Fortitude, 396.

- John Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, The United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific, CMH Pub 5-5 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1959), 9.

- Edward Drea, New Guinea, The Campaigns of World War II, CMH 72-9 (Washington, DC: The U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2019), 20.

- Carafano, Brutal War, 197–199.

- Edward Drea, New Guinea, The Campaigns of World War II, CMH 72-9 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2019), 18.

- Australia, Division of National Mapping, The Kokoda Trail [cartographic material], 1969.

- Miller, Cartwheel, 13.

- James P. Duffy, War at the End of the World: Douglas MacArthur and the Forgotten Fight for New Guinea, 1942-1945 (New York: NAL Caliber, 2016), 215.

- FM 3-0, Operations, 3-6.

- Duffy, War at the End of the World, 219.

- Duffy, War at the End of the World, 219.

- Stephen R. Taaffe, MacArthur’s Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 45.

- Taaffe, MacArthur’s Jungle War, 45.

- CJCS, Joint Capabilities and Integration Development System Manual, B-G-F-2.

- General Headquarters General Staff, The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, vol. I, Reports of General MacArthur, CMH Pub 13-3 (U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1994), 105.

- Mike Eckel, “How Did Everybody Get The Ukraine Invasion Predictions So Wrong?,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 17 February 2023.

- Harun Yilmaz, “No, Russia Will Not Invade Ukraine,” Al Jazeera, 9 February 2022.

- Lionel Gage Wigmore, The Japanese Thrust, 1st ed., vol. IV, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1-Army (Campbell: The Australian War Memorial, 1957), 18.

- Maurice Matloff and Edwin Snell, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare 1941–1942 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980), 2.

- Carafano, Brutal War, 17.

- Matthew Tetreau, “Where the Wargames Weren’t: Assessing 10 Years of U.S.-Chinese Military Assessments,” War on the Rocks, 22 September 2023.

- Robert Reilly and Cleo Paskal, “China’s Pacific Campaign: Preserving US Interests in the Indo-Pacific,” 25 September 2023, in Westminster Institute Talks, produced by the Westminster Institute, podcast, 01:11:60.

- Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs, Preserving U.S. Interests in the Indo-Pacific: Examining How U.S. Engagement Counters Chinese Influence in the Region, 118th Cong., 1st sess., 16 May 2023, 118-29.

- The Associated Press, “Solomon Islands Signs Policing Pact with China,” NPR, 11 July 2023.

- Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian and Eric Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 January 2023.

- Timothy Bonds et al., What Role Can Land-Based, Multi-Domain Anti-Access/Area Denial Forces Play in Deterring or Defeating Aggression? (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017).

- Andrew F. Krepinevich, Archipelagic Defense 2.0 (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, September 2023).

- Krepinevich, Archipelagic Defense 2.0, 11.

- Krepinevich, Archipelagic Defense 2.0, 128.

- Charles Flynn and Sarah Starr, “Interior Lines Will Make Land Power the Asymmetric Advantage in the Indo-Pacific,” Defense One, 15 March 2023.

- The World Bank Group, “Vietnam,” Climate Change Knowledge Portal, 2021.

- Flynn and Starr, “Interior Lines Will Make Land Power the Asymmetric Advantage in the Indo-Pacific.”

- Krepinevich, Archipelagic Defense 2.0, 142.

- Joseph Biden, National Security Strategy 2022, The White House, October 2022.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.