Myths and Principles in the Challenges of Future War

Myths and Principles in the Challenges of Future War

by LTC Amos C. Fox, USA

Land Warfare Paper 23-7, December 2023

This publication is only available online.

This is the second article in an AUSA series examining the future of armed conflict. The first in the series, Western Military Thinking and Breaking Free from the Tetrarch of Modern Military Thinking (Landpower Essay 23-6, August 2023), is available here. This installment scrutinizes a compilation of arresting myths which inhibit the cognitive maturation of Western militaries to address the challenges of contemporary and future armed conflict. To counterbalance these myths, we also provide a set of standards grounded in the belief that technological innovation has a quick decay time; this is because self-organizing adversaries always respond in self-preserving strategies to battlefield novelty.

In Brief

- A set of myths in contemporary military thinking are holding back a broader appreciation for the challenges, opportunities and solutions for future war. The neglect of adaptive and self-interested oppositional innovation is the theme that binds each of these myths; ultimately, it is why they provide limited utility for the practitioner and scholar of armed conflict.

- Principles of war each have an inverse quality that—like that of a negative of a photograph—is just as important as the principle itself.

- The purpose of the principles outlined in this article is two-fold: first, to spur a penetrating examination of conventional wisdom by breaking the tyranny of the institutional hive-mind; and second, to provide the intellectual stimulus needed to energize the origination of theories and concepts that are compatible with the reality of armed conflict and are adequate for the future of war and warfare.

- War is the strategic considerations of armed conflict; warfare is the operational and tactical considerations, namely, where actual combat occurs.

- Preparing appropriately for the future of war means accounting for contingencies, not just for preferential outcomes.

Introduction

Western military thinking during the previous 20 years has been focused on using non-linearity and emergent behavior to try to explain the workings of military forces, to include state militaries, non-state actors and contractual proxies. The allure of precision is that it compounds many Western states’ preference for short, decisive and bloodless conflicts. In this environment, Western military thinking elevates precision strike to panacea status—it can solve almost every military problem and cause no harm while doing so. The spirit of this idea comes across in press releases and question and answer sessions with defense and policy leaders. The addition of the adjective precision finds a discrete place in many of the speeches and policies outlined by Western political and senior military leaders. The subtle weaponization of this word indicates that it has become its own end. Precision thus operates in a self-referential system in which it is at the same time an end, a way and a means, all of which supposedly decrease risk. The outsized emphasis on precision strike has caused strategy to shift from a tool to address military problems holistically to something known as “issue management via a targeting process.” Another way to describe this dynamic is by defining it as a strategy of point tactics.

Western military failures in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya highlight precision and the strategy of point tactics’ shortcomings as a collective pillar of strategic impetus. Further refined precision-heavy thinking, such as Multi-Domain Operations (MDO), Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) and Convergence, continue to reflect an “issue management-via-targeting process” and a strategy of point tactics approach.

The emphasis on precision and the strategy of point tactics reverberates off of the flawed belief in anticipated “decisive” points. Theorist Liddell Hart notes that decisive points are often only identified as decisive post facto, and often by historians, and not by military professionals.1 The logic underpinning the causality between precision strikes’ effect on so-called decisive points remains buoyed on the belief in centers of gravity (COGs). COGs are believed to be akin to an Achilles heel; if appropriately attacked, their weakening can trigger strategic paralysis in an adversary and the adversary’s subsequent collapse with nary a fight.2 Despite its theoretical appeal, the COG concepts lack sufficient intellectual rigor and empirical evidence to make it anything more than a good idea.

Scholars such as Cathal Nolan and Anthony King, on the other hand, illustrate empirically that armed conflict among industrialized states is won through tactical attrition which, when compounded across a theater of war, generates operational and strategic exhaustion.3 Nolan and King’s findings, coupled with assertion that strategic discourse is degenerating into an emphasis of precision strikes on point targets, is of increasing importance as Western states examine the challenges that would accompany a conflict with China regarding its Taiwanese ambitions.

Myths

Today, vogue conceptual arguments, categorized as myths within this article, corrupt a clear-sighted understanding of both war and warfare, thereby reinforcing the “issue management-via targeting process” problem plaguing Western military thinking. These myths are (1) the belief that commanders and command nodes bear significant value on modern and future battlefields; (2) that small, light and more deployable forces are required to face the challenges of future armed conflict; (3) that the future of war will see a more transparent battlefield; (4) that one’s warfighting preference matters; and (5) that the defeat mechanism concept is legitimate, and, if so, that it is actually helpful. These myths, in turn, are the catalyst for revitalizing the principles of war heuristic, which is this article’s primary contribution.

Principles

These principles of war, first developed by J.F.C. Fuller in the early 20th century, and refined multiple times during his life, have remained relatively constant for a century. In recent years, theorists have broached the topic, especially as they relate to the future of armed conflict, with varying degrees of success. Despite these attempts to help improve the principles that underpin much of Western military thought and the associated strategic processes, many Western militaries continue the worrying trend of relying on stagnant, centuries-old ideas and easily falsifiable principles and heuristics as the bedrock of their thinking.

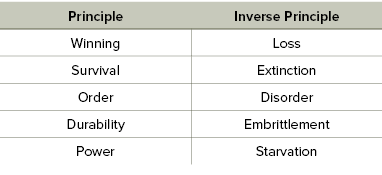

Principles of war should instead be based on rationale sourced from the marketplace of ideas and anchored on the attitude that the science of war exceeds the bounds of ideology. Institutional bias has no place in the development of basic concepts of war and warfare. In that spirit, this article posits that five basic principles guide war. Further, each of these principles has an inverse principle. Accounting for inverse principles is important because it ensures that self-interest does not cloud the necessity of seeing war and warfare through the lens of multilateral competition in which all participants pursue strategic victory. As theorist B.H. Liddell Hart cautions: “War is a two-party affair. Thus, to be practical, any theory must take account of the opposing side’s power to upset your plan. The best guarantee against their interference is to be ready to adapt your plan to circumstances, and to have ready a variant that may fit the new circumstances.”4

The principle and inverse principle reflect each other and, when viewed collectively, they represent the bedrock principles that underpin how a military force must be oriented for war. These five principles are: (1) winning; (2) survival; (3) order; (4) durability; and (5) power. The inverse principles are, respectively: (1) loss; (2) extinction; (3) disorder; (4) embrittlement; and (5) starvation.

It is important to note that these principles are focused on war, and not warfare, meaning that they address a state and their military’s strategic considerations for armed conflict. Principles of warfare, or tactical and operational level principles concerned with warfighting, will be addressed later in this series.

Part I: Myths of Modern Military Thinking

Myth 1: The Command Myth

Great Captains

The conventional wisdom among military experts suggests that a linear relationship exists among battlefield victory, command and control, and military leadership.5 This relationship is as old as war itself. Perhaps no historical example better illustrates the causality associated with the Command Myth more than the Napoleonic War’s War of the Third Coalition. In this conflict, heads of states, and other lesser political dignitaries, often either led their armies into battle, or at least accompanied them on the battlefield.6 Because of this political-military configuration, a significant and definitive military victory over an adversary often generated an outsized geopolitical impact. Battle, due to the proximity of the head of state to the death and twisted metal of victory or defeat, was the currency of armed conflict.7 Further, most armies of this period, and those operating in conscription systems, required significant supervision to prevent desertion. Therefore, eliminating military leaders could cause disorder to overtake conscript-based armies, whereas eliminating the head of state—or, at a minimum, eliminating the political leader’s army in a battle—could bring that state or polity to heel.

The War of the Third Coalition fit the causality model outlined in the preceding paragraph. Napoleon and a small coterie of his allies defeated a European coalition of several states and small polities. Having already defeated Austria during the Ulm Campaign, his army pulverized the Russian army at Austerlitz, resulting in Austerlitz emerging as his pièce de resistance.

During the Battle of Austerlitz, the heads of state of France, Austria and Russia were all present on the battlefield, which is why the battle is also referred to as the Battle of the Three Emperors.8 The emperors’ presence ensured that no geopolitical dithering or mission creep followed. Thus, France’s victory at Austerlitz forced the soirée of emperors to make definitive, quantifiable decisions about the war’s outcomes. The resulting Treaty of Pressburg encrusted Bonaparte’s geopolitical position (at least temporarily), while leaving no question about Austria and Russia’s political and military defeat. In this configuration, a simple linear logic (Logic 1) existed: Leader → Will to Resist (see Table 1).

A leader’s presence is not just important to geopolitical decisiveness. Leadership and command nodes are important to militaries built on conscripts and uninspired soldiers. Leadership serves not only as a motivating factor in warfare, but also as a tool to implement and maintain order, where disorder would otherwise exist. In these systems, leaders maintain order over a relatively unmotivated mob so that they can use the mob as a vector of mass violence. In these types of systems, leaders are the keystone to their respective military’s central nervous system. In this type of system, decisions are made, information and intelligence are digested, and strategy and plans are formed at a leader’s location. A simple linear logic (Logic 2) exists in these armies: Leader → Order → Operate (see Table 1).

Table 1: Logics of War (Initial)

State militaries today are professional and purpose-oriented, unlike their conscript counterparts of the past. Today, noncommissioned officers (NCOs) absorb many of the tasks that senior military leaders and lower-level commanders once carried out. Modern militaries provide NCOs the responsibility of maintaining system order. As a result, senior military leaders and commanders along any chain of command are less important to system order than they once were. Because of this, modern militaries represent their state and support their state’s foreign policy and the associated military objectives. In the past, armies were more representative of a head of state and the local commanders, who maintained order and inspired the less dedicated soldiers to accomplish the head of state’s military objectives. This is where theorist Liddell Hart’s “Great Captain” theory of military leadership is borne. Despite the fundamental changes in the causality and in the purpose of command and control, these ideas remain calcified in Western military thinking.

Today, militaries represent their state, and the state invests in its military. States are not interested in seeing their militaries defeated. Therefore, they build forces that are resilient and that have depth to persevere when engaged in sustained combat. A different logic is present in state-based armies that operate with volunteer forces. The logic (Logic 3) that guides volunteer, state-based armies operates according to the following logic: Perseverance → Order → Operate. Mission accomplishment, or victory, is the handrail by which all actors advance, albeit acknowledging that all definitions of victory are both fundamentally state (or actor)-specific, and not entirely known to an adversary, despite the best intelligence efforts.

In the logic of Perseverance → Order → Operate, the importance of commanders, headquarters nodes and command posts lose their luster. Logic 3 systems, in which most Western militaries operate, use a state-centric rationale, unlike the individual-centric rationale of Logics 1 and 2. In Logic 3, individual leaders are of less importance to the state than is their military’s ability to endure the rigors of battle while continuing to mission accomplishment. To be sure, Logic 3 produces very few General Bonapartes because the systemic rationale that underpins it is built on a “next leader up” approach, not on individualistic leadership. As a result, the “Great Captain” theory likewise also falls to the wayside as states emphasize impersonal, organizational leadership (see Table 2).

Table 2: Logics of War (Complete)

Logic 3 carries increasing importance in the future. The diffusion of artificial intelligence, machine learning and autonomous systems will further erode the importance of individual-minded approaches to command and control. Information, data, data processing and information networks, not individuals, will replace “Great Captains.” Human analysis will become decreasingly important as machines, having sifted vast amounts of information and generated a situationally prioritized list of options, relegate commanders to selecting options, authorizing high-risk missions and owning the aggregate effect of operations within their respective area of operations. If artificial intelligence, machine learning and autonomous systems assume their supposed position of importance in the future, “Great Captains” will be replaced by “Great Networks” and “Great Authorizers.” Legal responsibility will be one of the only significant remnants of command for human commanders.

Root Causes

Another significant problem with Logics 1 and 2 is that they do not appropriately address root problems in modern armed conflict. While they dominated 19th century battlefields, now fall apart when an adversary eliminates a force’s commander or command elements. This is important to highlight because 19th century military logic, captured in the works of Carl von Clausewitz and Antoine Jomini, remains the bedrock of contemporary military thinking. A comparative analysis of Clausewitz and Jomini’s works with Western military operations doctrine, for instance, provides a similar set of ideas. The ongoing presence of particular terms such as decisive point(s), center of gravity, and interior and exterior lines, among many others, are an example of how Logic 1 and 2 rationales remain foundational to modern military thinking.

Today, however, states use armed forces that can obtain information, can generate targeting data and can strike from increasingly longer distances. On today’s (and tomorrow’s) battlefields, information, information networks, forces and strategic purpose are (and will be) more important than individual commanders. In fact, commanders might actually inhibit deft and impactful military operations on future battles by being reluctant to make full use of the tools at their disposal. Networks and information are challenging, if not impossible, to eliminate today because they do not exist in the physical world. One might even argue that because networks and information are non-physical variables, they cannot be destroyed, but only disrupted. The destruction of a command post or headquarters, for example, does not destroy the information or the network pulsing through that command node. Instead, the strike only temporarily destroys the means through which a small number of humans interact with the information on a network.

Strategic purpose is another non-physical variable. Like networks and information, strategic purpose cannot be destroyed. Because heads of state do not lead their armies into armed conflict any longer, strategic purpose—embodied by the political decision and supporting military objectives to engage in armed conflict—thus remains an ethereal idea that exists in the minds of those operating on the battlefield.

In today’s period of armed conflict, in which Logic 3 enlivens military activity, military commanders, headquarters and command posts no longer carry the significance that they did when Logics 1 and 2 carried the day. As a result, an adversary’s force is the most important battlefield variable on the battlefield, rather than the commanders, command posts or networks. Although this perspective is controversial, it is important to examine this hypothesis in more detail.

Commanders, headquarters and command posts cannot operate without forces capable of accomplishing a mission. A commander with nothing to command is just an individual. Likewise, a headquarters or a command post with no forces to direct and support is just a collection of individuals occupying a workspace.

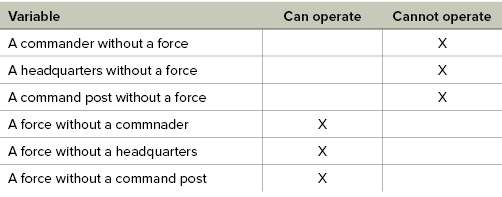

A force in the field without a commander nonetheless possesses the capability, purpose and information to accomplish its military objectives. A force in the field without a command post or headquarters can operate on strategic purpose or on their last orders, or it can be organized beneath another battle flag. Modern networks ensure that information flow, despite the absence of a commander or a command node, continues to pass through a military’s digital information networks. The absence of a commander is handled through the “next leader up” process of pragmatic problem solving, which is a feature of every modern state military and non-state actor military force. As a result, modern military forces can be expected to continue operating toward their military objectives until they no longer possess the physical means or the self-discipline to do so—or until they have accomplished their mission. Table 3 illustrates the causal effect of Logic 3 between command and forces.

Table 3: Logic 3, Command to Force Comparison

Considering the impact of Logic 3 on modern military operations, two broad topics can be deduced. First, as a rule, eliminating commanders, headquarters and command posts is incongruent with the established and well-worn routes to military victory. Commanders and computers are quickly replaced, but tanks, artillery and people are not. Systematically annihilating an adversary’s forces, on the other hand, not only stops its ability to advance its state toward their policy objectives;9 it also amplifies an adversary’s strain of industry, and it increasingly complicates an opponent’s strategic economic considerations in ways that eliminating a commander or command node cannot.

Second, a strategy that targets the elements of command through precision strike might heighten, not diminish, long and destructive wars. Considering the causality identified in Table 3, forces without commanders and command elements will fight on until they cannot, but a commander without a force can do nothing. The logic follows that the methodical eradication of an adversary’s military force from the battlefield will result in victory sooner than the elimination of commanders and command elements. Yet, reality tells us otherwise.

The U.S. military’s precision-strike campaign that has targeted al Qaeda and the Islamic State’s leadership throughout the Middle East, for instance, has routinely eliminated commanders as frequently as the seasons have changed. Yet both terrorist groups have weathered the storm of steel and maintain engaged forces.10 Further, military operations in Ukraine support the causality of Myth 1. Throughout the summer of 2022, Ukraine, with the assistance of U.S. intelligence, methodically eliminated upward of 15 Russian generals on the battlefield.11 The elimination of Russian generals might have disrupted their activities, but the impact on the specific battles, and the war as a whole, have been limited at best. Aside from generating a lot of chatter on social media in support of Ukraine, the strikes did little to accelerate Russian military defeat or to increase the odds of a Ukrainian military victory. In fact, many analysts suggest that the conflict is at a point of stalemate that Ukraine will not be able to overcome, regardless of the international community’s military and intelligence support.12 This is a position shared by Ukraine’s top military commander, General Valery Zaluzhny.13

Myth 2: Small, Light and Dispersed is Better

Conventional thinking among Western militaries and many analysts today suggests that small, light forces which are dispersed across a battlefield are best suited to address the challenges of future armed conflict.14 This suggestion is predicated on a belief in the increasing importance of “non-contact” warfare, or the idea that a state can sense an adversary with increasing clarity and at amplified distances, and, accordingly, strike the adversary from increased ranges with boosted precision.15

Further, a large amount of the advocacy for smaller, lighter forces references videos from the Nagorno-Karabakh War of 2020 and short, sensational video clips from the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, in which drones and precision strikes liquidate single tanks and small fighting positions.16 Reflecting on these snippets of finite tactical engagement, many commenters suggest that the lesson of these engagements is that large forces are destined to be identified and destroyed on future battlefields and that drones and precision strike are increasingly the answer to addressing land warfare challenges.17

Yet, stringing together disparate clips of discrete strikes and poor tactical acumen hardly represents analytical rigor, and it should not form the basis of supposed lessons learned, nor of recommendations to force structure changes. Viewing armed conflict through the lens of engagements and targeting processes can cause a state to inappropriately prepare for war, both strategically and tactically. States and their militaries must appreciate that wars are won through laborious and resource- extensive campaigns that exhaust an adversary.18

Moreover, the threat of nuclear war, which served as war’s bookend throughout the Cold War, provides an analog to the perceived challenges of battlefield transparency and long-range precision strike. Following World War II and the Soviet Union’s demonstration of nuclear capability, the U.S. Army asserted that large and slow formations would be quickly identified by Soviet reconnaissance and destroyed on the battlefield in tactical nuclear strikes.19 The Pentomic Division was thus the solution to the theoretical problem of being easily found and quickly destroyed by short- and long-range nuclear strikes.

Scholar Richard Kedzior asserts that the Pentomic Division, which intended to use dispersed operations with small, light and more readily deployable formations to counter the threat that nuclear weapons posed to large, heavy formations, was fraught with paradox when it was transitioned from theory to practice.20 Kedzior states that military leaders failed to account for a handful of important considerations. First, they failed to appreciate the true destructive power of tactical nuclear weapons, which exceeded the utility of small, light and dispersed forces. Second, the small, light and dispersed forces lacked the combat power and lift to deliver useful strikes, and distributed dispositions compromised the ability to mass and seize battlefield opportunities, or to conduct effective defensive operations.21 Third, the Pentomic Division’s small, light and dispersed forces created logistics nightmares due to the amount of time that sustainers were on the road.

R.F.M. Williams recalls that the Pentomic Division’s small, light and dispersed forces were to rely on “nuclear fire support, dispersion, speed, and mobility.” Moreover, a Pentomic Division’s subordinate forces required “hyper mobile” forces and a large logistics pool to feed “small, scattered supply points” that sustained forces close to the front. Yet, the U.S. Army could not cross the Rubicon and make the Pentomic Division meet the expectations of dispersed operations.22

The issues raised by Kedzior and Williams provide a good starting point to examine the call, yet again, for small, light and rapidly deployable forces suited for distributed operations. Both Kedzior and Williams’ points remain valid today, and will well into the future. In addition, three additional points must be raised. First, distributed operations by small forces will attract more attention, not less, from an adversary. A small force moving into and out of a location is likely more noticeable than a larger force operating in the same space. What’s more, it will be easier, not more challenging, to find important support and enabling elements in small formations than in larger formations because discrete units and capabilities are better hidden within larger formations.

Second, sustainment and logistics activities occurring within a larger formation tend to be less visible than in small formations, i.e., sustainment and logistics activities get lost in the background noise of a large formation’s continuous movement, striking and protecting. Similarly, small formation sustainment and logistics activities, absent some kind of internal generation of classes of supply, tend to telegraph the location of sustainment units, tactical warfighting units, headquarters and the connecting road networks. As a result, distributed operations by smaller, lighter forces simplify a watchful adversary’s targeting and reconnaissance process.

Third, small, light and dispersed forces are prone to piecemeal destruction. An opportunistic adversary can use a dispersed force’s distribution to its own advantage. The adversary can insert itself between disparate units, blocking reinforcement to one or more of the dispersed units, and eradicate the isolated units, one by one. Moreover, two additional challenges present significant hurdles to the necessarily of small, light, more deployable forces and to the problem of battlefield transparency.

Challenge-Response Cycle

Militaries operate within a competitive adversarial environment. Competing actors are perpetually engaged in a challenge-response cycle. In that cycle, for every nascent solution an actor introduces, the adversary will seek a response, and will correspondingly introduce its own novel solution to that problem. That cycle continues until exhaustion consumes one side, or one side decides it will no longer continue fighting.

Cautious of falling prey to circular logic, it is important to highlight that modern precision munitions, sensing, drones and long-range strike fit within the “challenge” phase of a renewed period of state-centric, industrialized international armed conflict. It is reasonable, therefore, to assume that second-mover states—and their friends, partners and allies—are contributing to the “response” phase of the challenge-response cycle by attempting to develop countermeasures to today’s novel warfighting capabilities. By virtue of the time lag that exists between a response’s ability to catch and generate parity with a challenge, the logic of linearity generally supposes that the technology and tactics of one actor’s “response” phase remain a step behind the technology and tactics of the adversary’s “challenge” phase.23

Today’s drones, long-range fires and GPS and radar innovations are examples of challenges at the fore of industrialized international armed conflict. Certainly, the military thinking community is replete with articles stating that drones and long-ranges fires are revolutionizing warfare and will continue to do so. Yet, much of the writing that originates from this thought does not account for a conflict’s adversarial context and how the challenge-response cycle shapes how competing states ebb and flow among advantage, parity and disadvantage.

Considering the fluctuation between challenges and responses in the context of armed conflict, it is reasonable to expect a limited and short-term impact of any technological innovation in war and warfare. Thus, it is incorrect to assume that lighter, smaller forces operating in a more dispersed manner are the answer to nascent technological innovation pertaining to precision strike, battlefield transparency and enhanced target sensing and identification without more comparative analysis. Perhaps instead is a more investment in counter-sensor, deception, counter-rocket and counter-missile technology can address futurist concerns and yet maintain the striking power of land forces. Moreover, the investment in those capabilities should possess a tactical and operational component, meaning that solutions should focus on small unit concepts and technology as well as on larger unit investment.

Small, Light Forces and the Challenges of Land Warfare

The “light footprint” approach possesses a vampiric quality in military thinking. From the failed Pentomic Division, to the inability to seal victory and prevent disaster in both Afghanistan and Iraq, to Russia’s flawed invasion strategy of Ukraine in February 2022, the light footprint always promises to convey the answer to the problems of future armed conflict, yet it always fails to deliver. Although this assessment is qualitative, a quantitative assessment would likely yield an even more incisive, and likely a more damning, finding. Therefore, prudence suggests that Western militaries should invest in exploration and experimentation in this area of research.

By the same token, military history does illustrate that large formations and large footprints are more adept and better enabled to address the challenges of land warfare. This is not necessarily due to their physical agility or dexterity, but to their ability to provide military commanders with the flexibility to address a range of challenges; a small, light force provides a limited flexibility due to its small size, limited range and lack of organic warfighting capabilities.

In practical terms, the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s mandate for a light footprint allowed U.S. forces in Afghanistan to quickly topple the Taliban-led Afghan government in October 2001. Yet, it failed to provide sufficient manpower to prevent senior leaders from the Taliban and al Qaeda from escaping into the mountains of Afghanistan and into Pakistan.24 Scholar Steve Coll asserts that the United States would have needed at least an additional 2,000 to 3,000 Soldiers to block al Qaeda’s disappearance into Pakistan.25 Moreover, the iterative cycle of troop surges in Afghanistan, which often accompanied changes in command of the war effort, also reflected the light footprint’s inability to provide military commanders with the tools they needed to accomplish their military missions.

U.S. General Tommy Franks’ insistence on a light footprint in Iraq provides another example of how that model fails military commanders. Franks’ plan for Iraq called for an small force—little more than a traditional U.S. Army Corps, plus the required joint force attachments—to conduct a significant military operation.26 Embracing information circulated by the Central Intelligence Agency, Franks built his plan on the belief that the United States would be welcomed by Iraqis as liberators following their victory against the Iraqi military. As such, there would not be a need for a large military because the United States would not be an occupying power; sovereignty would be quickly turned back over to the Iraqis.27 But, almost none of this happened. Iraq devolved into a massive, country-wide insurgency, and the U.S. military spent the better part of the next eight years trying to overcome it. A small, light force posture was not the answer to the land challenges in Iraq. As a result, President Bush authorized a troop surge and deployment extensions to keep pace with the deteriorating situation and evolving challenges occurring on the ground.28

Further, the U.S. military faces a unique dichotomy among most state militaries. The U.S. military is a globally expeditionary force. By virtue of seeking self-interest across the globe, a small, light military is preferable because it can muster quickly, board transport and be on the ground on the opposite side of the globe in relatively short order. This matters both for contingency operations and for larger military operations, such as the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

A paradox exists, however. The ability to move across the globe requires rapidly deployable forces, yet, land warfare possesses innumerable challenges, especially when the force that arrives is underprepared. The paradox emerges in that land warfare requires large forces that can handle a myriad of tests. Put another way, policymakers and strategic military leaders are often caught between deployability, which requires small, light forces and forces sufficiently robust to handle all the challenges of land warfare. Some of these challenges are known ahead of time, and some only emerge as militaries move through the challenge-response cycle.29 Moreover, many land warfare challenges, such as urban warfare, control of terrain and human-to-human engagement, cannot be overcome with long-range firepower, precision strike, stand-off strike, and other technological innovations. Instead, those challenges require individual Soldiers and their leaders, on the ground, making timely decisions that require human judgment, in the moment and in the context of the situation, to prevail.

Further, U.S. military forces must possess sufficient weight of force to conduct forcible entry. This can include anything from sea-borne land embarkation to airborne assaults. Because of the high margin for error associated with these operations, the margin for error, regardless of technological innovation, also increases. Therefore, it must be assumed that larger, more capable land forces, not smaller and lighter land forces, are needed to address the challenges of warfare in the ensuing decades.

Moreover, expeditionary warfare fundamentally means offensive warfare, for why else would a force deploy across the world to immediately assume a protective posture? Given the understanding that expeditionary warfare is synonymous with offensive warfare, the 3:1 attack-to-defense ratio should continue as the U.S. military’s vision for future force design.30 A small degree of that ratio can be compensated for with emerging technology, but history suggests that success in land warfare resides in the brute force of numbers, not in fanciful technology.

The light, small force looks attractive to government and military financial analysts, to the holders of purse strings and to the individuals who are attempting to gain influence over both of those groups. History, however, shows that such a force might accomplish an immediate war aim, such as toppling a weak government, but it does not provide military commanders with the strength, flexibility and stamina to address the military and civil challenges that quickly emerge after initial and indecisive military success. Moreover, as governments and militaries awaken to the inability of their small land forces’ inability to cope with emerging challenges in the subsequent phase of expeditionary operations, they often deploy more land forces, or they outsource some of those problems to proxy forces to address. If the light force myth wins the debate, the U.S. military—and its Western partners—must therefore be prepared to manage an increasing number of proxy wars. Lastly, the challenge-response cycle suggests that most initial benefits associated with the use of small, light forces would quickly be matched and overcome by watchful and self-interested adversaries.

Myth 3: The Looming Importance of Battlefield Transparency

Analysts and practitioners assert that the transparent battlefield is both an emerging concept in warfare and that it will revolutionize warfare. They believe that sensing capability is becoming increasingly relevant on battlefields because of the proliferation of drones, space-based monitoring capabilities and small land-based sensors.31 As a result, military forces will be under constant observation, and therefore, prone to enhanced and timely targeting and strike.32 Analysts David Barno and Nora Bensahel go so far as to state, “The future transparency of this expansive web of support should be nothing short of terrifying to U.S. military planners. . . . These factors have staggering implications for future Army doctrine, organizations and platforms.”33 Terrifying? No. Hyperbolic? Yes.

Every generation that experiences significant technological or process advancements in reconnaissance, surveillance, sensing and improvements in strike capability and process tends to find commenters quick to assert that surprise is a vestige of a bygone era of armed conflict. Technological innovation, they say, has created a transparent battlefield, in which military commanders and the intelligence community possess nearly infinite information on the operating environment and the forces located therein. Analyst Wilf Owen, for instance, highlights that the transparent battlefield has been a feature of armed conflict since at least World War I, and that battlefield transparency is an evolutionary aspect of warfare.34 Brigadier General Curtis Taylor also notes the historical precedent of battlefield transparency by referring to the use of aerial observation balloons and other information-gathering capabilities that date to the 19th century.35 Scholar B.R. Isbell records that theorists from as far back in time as that century, to include Antoin Jomini, have written that the growing number of battlefield sensors has rendered surprise all but obsolete on transparent battlefields.36

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that maintaining a higher number of a given type of system equates to dominance in that field. Take military satellites, for instance. According to the website World Population Review, the three states with the most military satellites are the United States (239), China (140) and Russia (105).37 No other state comes close to Russia’s third place position. The high level of classification of space-based military capability, however, makes it challenging, if not impossible, to validate these numbers. Nonetheless, World Population Review’s numbers are used within this section to help illustrate ideas about the transparent battlefield.

Dominance, however, does not always translate to applied dominance. History is replete with examples in which more of something, whether that be larger forces, more artillery, or more drones in the sky, does not pave the way to battlefield or political victory. A similar understanding should be applied regarding the future of sensing and its impact on armed conflict. The challenge-response cycle suggests that as states develop more sophisticated means to observe both the battlefield and the routes that expeditious forces will take to those battlefields, the adversarial state will make equal investments in ways to confound that sensing technology.

Theorist Robert Leonhard cautions that exquisite technologies, or those that significantly extend the range that military commanders can generate a high-impact battlefield effects, are often retained at higher levels of command. In non-Western militaries, in which freedom of action is not encouraged, one must assume this situation is even more prevalent. The assumption must then be made that a battalion or brigade, regardless of its status as Western or non-Western, is not going to be privy to sensing capabilities, or necessarily to sensing information which is not immediately relevant to their situation. A theater commander or field army’s sensor feed would no doubt overwhelm a battalion hundreds of miles forward, especially if it were doing anything above or beyond occupying an uncontested position on the battlefield.

As a result, battlefield transparency will provide momentary bursts of military advantage, but once an adversary identifies those breakthroughs, they will find methods to again obviate or circumvent transparency. Western militaries should therefore continue to invest in deception techniques and technology, as well as counter sensor techniques and technologies. Yet, Western militaries should also see battlefield transparency as just another application of “combined arms” and “jointness.”

The transparent battlefield does warrant a degree of caution, however. This caution is important for maneuver enthusiasts. Maneuver warfare on a transparent battlefield might well be suicidal. Positional and attritional warfare are the inevitable byproducts of unchecked technological innovation. If a transparent battlefield becomes a reality, for instance, a force’s dashing movements across unrestrictive terrain, in which an adversary possesses the power to identify, target and engage them in minutes or even seconds, means that that force could be annihilated before it even gets seriously involved in the conflict. Advancing on a transparent battlefield against an adversary equipped with an effective sensor-to-shooter network would welcome a significant bombardment.

Left unaccounted for, military operations on a transparent battlefield will evolve from maneuver-type operating toward something more akin to positional warfare with a strong attritional flavor. Instead of seeking battle against an enemy force in open terrain, an aggressor might hurriedly move from one location to the next, attempting to find obscurant terrain along the way, while seeking a beneficial position proximal to its adversary—perhaps in a city—to bring that adversary to battle. Transparency, if it does materialize, will turn the battle into a positional affair and will turn wars into attritional slogs.

Further, a military force’s sensor-to-shooter network might be so prohibitive to movement that both sides move into urban areas and conduct duels of long-range precision strike with one another. In this situation, a force might only be willing to move if its adversary’s sense, strike and protection systems have been eliminated to a condition sufficient for that adversary to use harassing strikes. This situation—movement to destroy with fires—is not a high-minded take on maneuver warfare in a sensor-to-shooter rich operating environment, but rather the long overdue acknowledgement of positional and attritional warfare’s relevance in armed conflict.

Myth 4: Warfighting Preference Matters

The perceived importance of warfighting preference is a theme that permeates military thinking. Maneuver warfare is one of the prominent features in this discussion today. Many distinguished and well-respected scholars and analysts have successfully made the case in recent years that maneuver warfare is not the acme of warfighting prowess, but just one way of warfare that can only occur if the situation and conditions permit.38 Nonetheless, the cult of maneuver is quite strong in Western militaries, despite the concept not delivering on its associated hype. This has led some scholars and analysts to ask if maneuverist thinking is a doctrine or a dogma in Western military thinking.39 The same situation holds true for conflicts characterized as irregular wars. In many of these conflicts, which Western militaries state that they are working through “partners,” when in reality, they are using third-party actors as proxies for their own forces, pursuant to their own self-interested objectives.

Western militaries tend to be surprised when a conflict, such as the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, takes on an attritional hue, or when a proxy conflict emerges from a military operation intended to support a friendly state or non-state actor. Despite a state’s best wishes, warfighting tends toward attrition because:

a) an adversary will always operate in a way that provides it with the best opportunity to survive and win; and

b) an adversary will operate in ways that suboptimize how their opponent wants to operate and how they are built to operate.

Moreover, operating through an intermediary actor, whether that actor is a state or non-state actor, and having them engage in combat in lieu of one’s own forces and in pursuit of one’s self-interest is, by definition, a proxy war. But by obfuscating the reality of proxy actor engagement, Western militaries put themselves at a disadvantage by not being prepared to understand how to account for proxy agency costs.

Reality, on the other hand, demands that a state possesses a multifaceted capability to fight in a host of hostile environments, against and with a variety of state and non-state actors. Reality demands that a military possess a broad understanding that neither vectors its understanding of warfare nor optimizes its training for a preferential way of warfare. A military’s insistence that it will not participate in operations in urban environments or in proxy wars, or that they will not engage in attritional warfare, for instance, are a few common preferential states offered by Western militaries.

Nonetheless, these proclamations are hollow aspirations. Four factors determine how a military must fight. First, the physical environments are deterministic. Many physical environments, such as urban areas, heavily wooded areas, or waterways, inhibit mobility and thus deny maneuver warfare beyond the smallest tactical elements. Try as one might, if the physical environment dictates a plodding methodical way of operating, then maneuver must remain an aspiration. Second, time exerts pressure on military forces and therefore influences the strategy, operations and tactics of both sides in a conflict. Time is linked with opportunity, and it rewards the military that is most responsive to opportunity rather than the one with perfectly planned and resourced operations. Third, a military force must consider its adversary. An adversary’s method of fighting, the location in which they elect to fight and their respective force design all influence how a military must account for that adversary on the battlefield. Fourth, one’s preference for fighting can be considered. Moreover, one’s preference should not be considered ahead of any of the four variables, but in coordination with them.

Myth 5: Defeat Mechanisms

U.S. Army doctrine defines Defeat Mechanisms: “The method through which friendly forces accomplish their mission against enemy opposition.”40 Defeat Mechanisms are communicated through the application of one of four tactical mission tasks: destroy, dislocate, disintegrate and isolate.41 Two significant problems, however, make the Defeat Mechanisms incompatible with the trajectory of armed conflict moving into the future.

First, the Defeat Mechanism is a mechanical heuristic, developed for a period in which warfare was less dependent on the interconnection between individual implements of warfare and more dependent on the communication between echelons of command. Moreover, Defeat Mechanisms were not borne from analytical rigor; rather, they were crafted by doctrinaires at Fort Leavenworth as a cheap and easy tool to help planners, staffs and commanders to communicate how they envisioned tactical defeat.42 Theorists and scholars such as Frank Hoffman and Eado Hecht attempted to add intellectual rigor to Defeat Mechanisms, but that work is post facto.43 In future warfare, however, artificial intelligence, machine learning, autonomous systems and many other information-driven, network-based tools will force the concept of defeat to exist on a plane greater than the purposeful impact on an adversary’s physical tools of warfare. Instead, defeat will result from a state’s ability to exhaust its adversary’s warfighting system through interconnected operations targeting the adversary’s physical force, the information it needs to make decisions and the time it requires to make effective decisions. In this system’s warfare environment, in which system exhaustion is the surest path to battlefield success, Defeat Mechanisms are passé.

Second, considering the importance of systems thinking, Defeat Mechanisms fail to reconcile how networks and information-driven systems insulate battle command—from the tactical to the strategic levels—from physical destruction. Destroying a computer on a network, or destroying a tactical command post, for example, does not destroy the information on the network. It only delays information from reaching its intended user on that network. As a result, the data on the network, not the physical manifestations of the network (i.e., computers, servers, command posts, etc.) and the network’s feedback loops should be the focal point for Western militaries seeking to defeat adversaries on future battlefields.

Considering the importance of systems thinking on how states and non-state actors operate in armed conflict, it is imperative to understand that networks are defeated when data on the network is not trusted. Period. Of secondary consideration, networks are defeated when the information needed to make the network function moves in insufficient quantity through the network to fuel the feedback loop process. Moreover, networks are defeated when the information on the network flows at too great a speed for the network, or the humans on the network, to manage the flow of information. Finally, networks are defeated when the information on the network is corrupted to the degree that it presents a false sense of reality and, therefore, encourages poor decisionmaking in an adversary.44 The Defeat Mechanism heuristic, which is anchored on attacking an actor’s physical means, and does not reflect the realities of system warfare, is a myth much like the transparent battlefield, which comes with vampiric qualities in that it seems to resurface whenever Western militaries begin examining how to operate in armed conflict.

Defeat Mechanisms, the product of sequential, mechanistic thinking about armed conflict, do not appropriately account for time in armed conflict. Time’s importance to systems thinking and systems warfare cannot be overstated. Scholar Andrew Carr posits that savvy commanders use fast or slow tempo operations to bend time to their advantage and to help accelerate an adversary’s defeat.45 Considering the importance of systems thinking in the future of armed conflict, time holds a germane position as it relates to military and strategic defeat. Time is manipulated in warfare through the tempo of operations. Speed is not always the best operational or tactical solution to a military problem.46

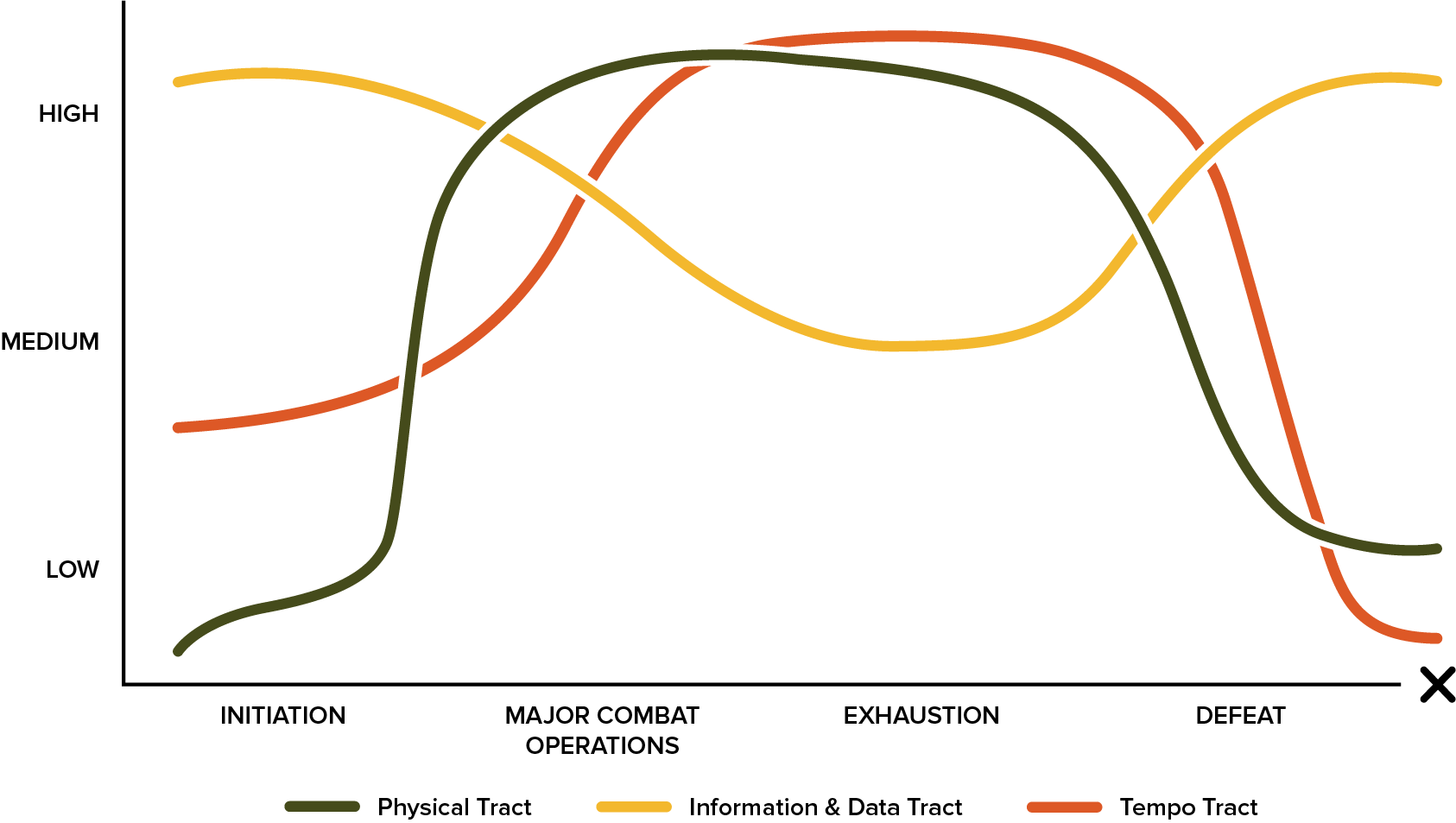

With defeat as the watchword, the Defeat Mechanisms construct should be cashiered for a heuristic better suited for the realities of modern and future armed conflict. As a result, any resulting warfighting heuristic should organize around the ability to fight jointly, to apply combined arms and to operate in multiple domains to the point at which defeat is obtained. Defeat is generated by exhausting the enemy’s warfighting system, not through the destruction, isolation, dislocation or disaggregation of any part (or parts) of their fielded forces. Defeat is generated through the combined effort of three pillars of activity—physical action, data and manipulation of time and information. Each pillar consists of its own set of tasks, and they are linked through interwoven tracts that advance to defeat. As the use of the phrase interwoven tract implies, the progression to defeat is neither linear nor binary; rather, it is a responsive heuristic that is sensitive to changes in the environment. To generate defeat on future battlefields, however, a combatant must use the interwoven tracts of physical destruction, data and information manipulation and tempo exploitation to exhaust an adversary, and thus bring about an adversary’s operational or tactical defeat.

Figure 1

Figure 1 provides a representation of the interwoven tract alternative to Defeat Mechanism. The X-axis represents a notional phasing construction to illustrate how physical, data and temporal elements of warfare can be synchronized to create a general phasing construct. Initiation, Major Combat Operations, Exhaustion and Defeat are the four major components articulated along the X-axis. These components represent the major benchmarks a combatant might encounter using the interwoven tract heuristic to visualize how to defeat an adversary. Along the Y-axis are general measurements—high, medium and low. The graph does not quantify any of these measures because that degree of fidelity is not needed to help illustrate the point. Within the graph, the physical tract, information and data tract and tempo tract are illustrated by different types of lines. Their differing positions along the X-axis illustrate how a state or non-state actor might utilize each of them, in relation to the other, during each phase of the operation, to advance their opponent from the initial conditions of conflict, through major combat operations and into exhaustion and subsequent military defeat.

Part II: Principles of War

It is important to return to the idea of first order principles. Due to their ontological differences, a separation between principles of war and principles of warfare is required. Scholar Christopher Tuck states that war is a state’s acts of policy and military strategy that pertain to a specific conflict. Warfare, on the other hand, is the action taken by a state’s military force (or a non-state actor) pursuant to the state’s war aims.47 Because of this structural difference, the utility of principles improves at each level when the principles are focused at the appropriate level. What follows is the introduction of five revised principles of war, as well as their inversions. Principle inversion is the result of having changed a principle’s orientation. In terms of photography, think of principle inversion as a negative. If winning is a principle of war, for instance, then denying an adversary victory, or defeating the opponent, is the inverse principle. The inverse principle reflects what a state must appreciate about the principle, but as it relates to an adversary. Each principle of war listed within this article carries with it an inverse principle. Table 4 provides a consolidated grouping of principles of war and their inverse principles.

Principle #1: Winning

The dialogue on victory or failure in armed conflict has become too esoteric, and likewise, strategic theory, in some cases, has become too theoretical. Discussions on victory in armed conflict are bypassed altogether as deliberators trip over academic phrases such as “theory of victory,” and what that phrase means, more so than generally defining victory.48 Moreover, strategic theory is on the verge of jumping the shark as theorists push the bounds of logic by overlooking the binding effect of resource scarcity on a policymaker’s range of military operations. Further, popular theorists also suggest that victory in war is of no concern to the strategist, because the acme of strategy is not the finality of military victory; rather it is remaining engaged in the strategic competitive environment.49 These types of assertions provide good thought experiments in staff colleges, but they hold little value in the real world.

Setting aside unhelpful theories, the simplest and most impactful strategic logic is that states strive to win in war. Of secondary importance, strategic actors define their own respective definition of victory, and those definitions of victory are gradient scales.

The Russo-Ukrainian War is instructive for gaining an appreciation of definitions and gradient scales of victory in armed conflict. From the beginning of Russia’s February 2022 re-invasion, many experts have jockeyed for prime position in the public eye by making bold predictions about the status of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Since the week of the conflict, experts have forecasted that Russia’s military was at the precipice of defeat and that Russian society could not, and would not, accept the war’s economic impact, nor its need for soldiers to replace losses on the front. Yet, most experts have been wrong. Russia’s society has weathered the hardships, and its military has moved on from operating the way that it wanted to fight and has adopted forms of warfare that better align with the situation and their war aims.

War aims are important to consider when addressing the “compete to win” principle of war. A state’s policy goals for a war are the true benchmark of victory. They might be in the public record, or they might be kept behind a veneer of truth. More important than this, however, is that they might align to a gradient scale along which maximum and minimum acceptable outcomes are the bookends.

This is important to understand because it makes “compete to win” a principle that exists on a sliding scale; while a state might think that it is effectively advancing toward victory, it is eliminating the possibility of its adversary to unlock maximum acceptable war aims. Yet, the effort it has exerted by this point has reached an inflection point and has exhausted its ability to aggressively continue the conflict. Its adversary marks its maximalist gains from its play sheet and moves on to lesser war aims—aims, however, which are no less critical to their definition of strategic victory.

Returning to the Russo-Ukrainian War helps illustrate this idea. Synthesizing the amount of forces Russia has put into the field and its initial military operations suggests that its aims were never focused on occupying all of Ukraine, nor on defeating Kyiv’s military. Instead, it appears that they were focused on eliminating the sitting Ukrainian government, replacing it with a Kremlin-friendly government, occupying Ukraine from the Dnieper River east to the Russian border, and eliminating any Ukrainian military forces that stood in the way of accomplishing those goals. It is useful to be realistic about the limits of Russia’s meta-strategy.

Within this meta-strategy, a set of subordinate strategies broadened and deepened the Kremlin’s definition of victory. The retention of the Donbas and Crimea remained central points of emphasis; thus, that retention is a subordinate strategy. The linking of the Donbas and Crimea along the much sought after “land bridge” was another of the Kremlin’s significant strategic aims—another subordinate strategy.

The interplay of subordinate strategies within the context of meta-strategy is important to appreciate because gradients of strategic victory exist in a state or non-state actor’s reliance on subordinate strategies. Put another way, subordinate strategies illustrate a state’s decreasing definitions of strategic victory. For instance, if the Kremlin’s overall definition of strategic victory was the annexation of the portion of Ukraine from the Dnieper River to the western Russian border, which could be viewed as its maximalist definition of victory, then the gaining and maintaining the land bridge to Crimea—and the retention of the Donbas and Crimea—could be viewed as the Kremlin’s minimal accepted outcome in the conflict. Kyiv’s ability to inflict territorial loss greater than the latter point might be perceived within the Kremlin as strategic failure. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of hypothetical Russia definitions of victory in Ukraine.

Figure 2

Appreciating a state’s definition of victory as a gradient scale helps in understanding that victory in war is not an all or nothing game; instead, it often operates on a scale of acceptability. Not appreciating a state’s definition of victory can result in an adversarial state misjudging how close, or how far, they are from victory. Nonetheless, all states should anticipate that their adversaries will fight vigorously for victory, whether that’s maximalist meta-strategy goals, or minimalist subordinate strategy aims.

At the same time, armed conflict—in which death and destruction are the currency with which victory must be purchased—is uneconomical. Indulging in armed conflict with no intention of victory is wasteful, and it is a luxury that few states can afford. States and militaries not intent on victory squander their resources from across not only the military, but also the diplomatic, informational and economic elements of national power. Therefore, it is imperative for a military force to win in armed conflict and to usher their adversary across the threshold of defeat.

Principle #2: Survival

Modern militaries are self-aware organizations. Self-aware entities pursue survival above all other goals. In armed conflict, to survive means to continue existing despite environmental challenges, threats or dangers. In armed conflict, being self-aware and focused on survival causes modern militaries A military force’s access to data and information, controlling the rate of operations and maximizing its protection are just as germane to its survival as the force’s need to maintain the power to gain proximal, situational dominance at important places and times on the battlefield.

Military forces operating with self-awareness and self-organization indicate the presence of the logic of systems theory in modern military forces, their operations, how they interact with their superior and inferior partners and how they interact with a dynamic world around them. Feedback loops are the critical link between military forces and all the environmental variables that impact their survival. Considering the logic of feedback loops, in which data and information from the outside world is collected, analyzed, synthesized with internal information, and distributed across the organization, a military force’s survival is inextricably linked to the possession of accurate information, the safeguarding of internal information and the redundancy of data and information networks.

The inversion principle of survival is extinction. The military force that is adhering to the principle of survival is also working to extinguish their adversary, and vice versa. Data and information are just as important to extinction as they are to survival. Therefore, a force seeking to extinguish an adversary should ruthlessly strike at the latter’s data and information and at their information processing systems.

Principle #3: Order

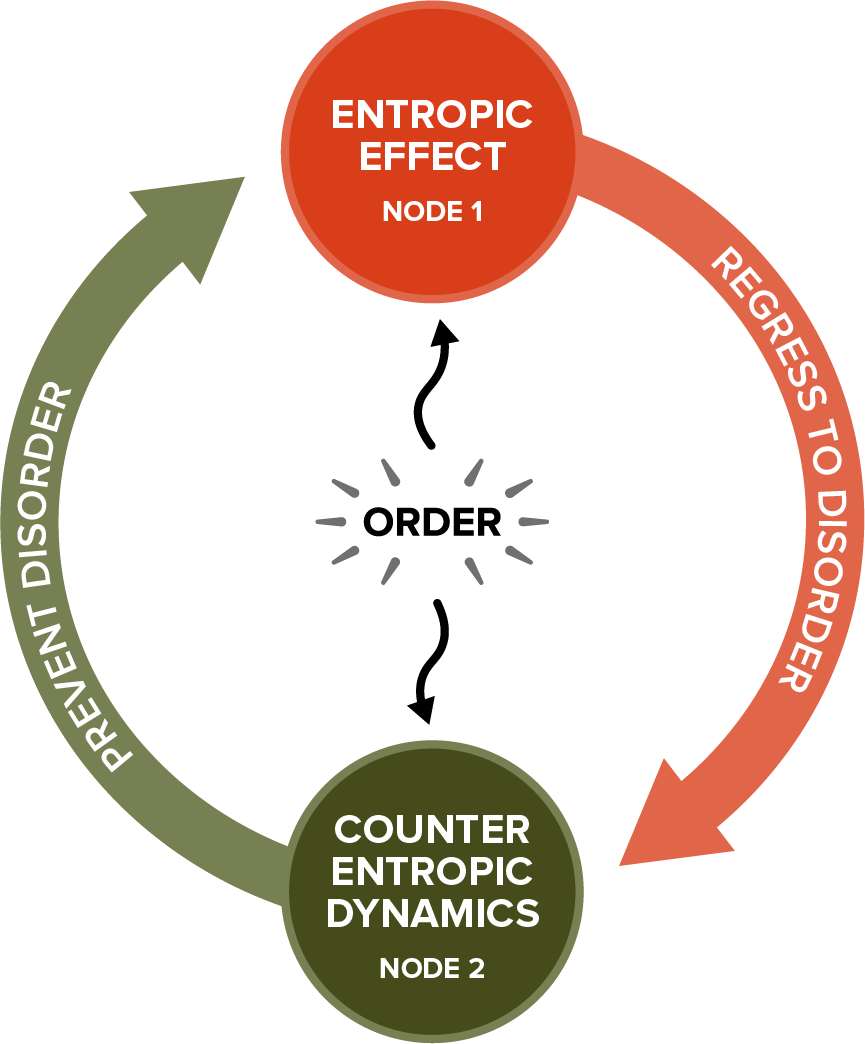

The concept of entropy, in which all systems tend toward disorder, is an important consideration when regarding the practice of war and warfare. Both in garrison and in combat, military forces are always moving toward a state of disorder. In militaries, entropy is the degradation in capability (i.e., the physical ability) to accomplish tasks and missions and in the depreciation of capacity (i.e., the people and organizations) to achieve objectives and fulfill assignments.

Modern militaries are self-organizing, self-aware and open, learning systems. Because of this, modern militaries do not allow entropy to run rampant. They offset the constant repercussions of entropy through tasks such as recruiting, training, proactive medical care, preventative maintenance, sustainment activities and education.

The relationship between entropy and military forces is a cycle in which military forces seek order, whereas the natural force of entropy fuels disorder (see Figure 3). One way to visualize this idea is to place “entropic effect” and “countering entropic dynamics” as poles in a cycle chart, labeling the former “Node 1” and the latter “Node 2.” The arm that connects Node 1 to Node 2 is all of the naturally occurring activities inherent to entropy in military forces, plus the adversarial injected activities that further accelerate disorder in an opponent. The arm that connects Node 2 to Node 1 consists of all the naturally occurring tasks that a military force does to overcome naturally generating disorder, plus everything that it does to compensate for and overcome adversarial caused disorder.

Figure 3: Entropy-Counterentropy Cycle

As Figure 3 alludes to, disorder is a military force’s natural state of existence. The devolution to disorder accelerates when an adversary is added to the equation. Thus, war is the process of a military force overcoming the natural and adversarially generated components of disorder through attentive monitoring of environmental and internal conditions, modulating its own activities to counter entropy’s negative impact on its ability to accomplish tasks and to complete missions. Therefore, if disorder is a military force’s natural state of being, then order is a military force’s foremost objective, and the pursuit of order is its main concern.

Disorder is order’s inverse principle. It follows that a military force must always operate in ways that advance its own order and accelerate disorder in its adversaries. Operations are one way to intervene in the order-disorder cycle, but battlefield architecture and force design are additional ways to influence order and disorder in war. Appreciating an adversary’s preferential warfighting techniques, its supporting logistics operations and how its force is designed to accommodate both factors is important because they provide the logic for how militaries should think about organizing the battlefield—from the strategic to tactical levels. The topic of battlefield architecture and how to align the principles of war with one’s strategy, tactics and force design will be discussed in detail in a later article in this series.

Principle #4: Durability

Durability is a military force’s capacity to absorb shocks, to recover quickly from adverse situations or conditions and to maintain structural integrity. Military forces must be able to operate in austere environments for extended periods of time in order to win their respective operations and to survive with sufficient power to maintain order over themselves and the emergent situation(s).

Durability is a principle of war, especially for Western military forces, because they are required to conduct expeditionary military operations. Considering this factor, at the outset of military operations, Western military forces conduct offensive operations against fortified adversaries determined to protect their forces and their interests from invading Western military forces. Given that adversary forces are likely defending important terrain, such as seaborne-handing sites, airfields or potential drop sites, one can then assume that materiel destruction and loss of individual soldiers in those critical locations will be increasingly high. Therefore, Western military forces require durability to sustain the initial shock of contested expeditionary operations, but, equally important, Western military forces require durability to conduct objective-oriented operations after successfully landing at embarkation points.

The principle of durability obviates the idea that smaller, lighter forces are the answer to contemporary and future challenges in armed conflict. The principle of durability suggests that military forces—especially those on the sharp edge of tactical warfighting—should not be designed with slim margins, but rather, with sufficient personnel, equipment, warfighting systems and units to overcome the rigors of armed conflict against an adversary who is determined to win.

Further, the urbanization of warfare is a prevalent trend in modern armed conflict. Scholar Anthony King also provides context, writing: “Force size may seem banal and unimportant, but in fact is has typically played a significant role in the character of military operations. . . . In the twentieth century, when states possessed massive armies, they were able to dominate urban areas through force of numbers. However, as forces have downsized, states have struggled to control urban areas.”50

Moreover, King contends that cities offer adversaries and weaker opponents “the best opportunities for evasion, concealment, ambush and counterattack against the technologically superior weaponry of state forces.”51 King’s arguments, fresh among scholars and practitioners, suggest that smaller, lighter forces are not the answer to problems of current (and future) armed conflict. Rather, larger and more durable forces are required.

Embrittlement is durability’s inverse principle. If a state is maintaining the depth and width required to address the significant challenges of both expeditionary and joint force supported land warfare, then avoiding brittleness is important. Deceiving an adversary into situational embrittlement is also a key principle of war. In the applied sense, embrittlement is arriving for a conflict when ill-suited for its environment and threats and its temporal and situational character. If properly set up and acted upon, an embrittled adversary can quickly move through its available resources or be in a physical position in which it is unable to access resources or other means of support, thus being more prone to military defeat.

Principle #5: Power

Power relates to possessing the bases of power required to enable campaigns, operations and battles. Power is predominately the physical means and supporting systems that enable and sustain military operations. Depth in power allows a military force to exhaust an adversary and is directly proportional to a force’s existing bases of power, coupled with its state’s emerging and latent bases of power. Power and bases of power have proven their strategic importance in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. Ukraine’s ability to energize emerging bases of power throughout the international community, as well as Kyiv’s ability to mobilize latent sources of power through a variety of domestic reforms, has allowed Ukraine to fight Russia to a draw.

Russia, on the other hand, relied on its own internal base of power. As Kyiv’s military forces thwarted the Kremlin’s attempted putsch in Kyiv and pushed Moscow’s forces into isolated positions in the Donbas and in southern Ukraine, Russia tapped into emerging and latent bases of power to energize its forces and to maintain its ability to keep a grip on its territorial acquisitions in eastern and southern Ukraine. Russia has had to reach out to China, Iran, North Korea and other smaller states for military support. As the Russo-Ukrainian War illustrates, power is a critical principle of war and one that enables a state’s ability to engage in armed conflict.

Starvation is power’s inverse principle. Starvation is a state’s ability to choke off an adversary’s access to the richness of its base, or bases, of power. By starving an adversary’s access to its bases of power, a military force can cause the adversary to become brittle and prone to exhaustion. While this will not spell instantaneous defeat, it will, as history has demonstrated, hasten a state’s force toward defeat.

Table 4: Principles and Inverse Principles of War

Conclusion

To address the challenges of the future of armed conflict, Western military thinking must expand beyond the confines of engrained institutional thinking. It must periodically question its assumptions and its extant mental models. To keep pace with change, it must discharge obsolete ideas and concepts, regardless of how uncomfortable doing so might initially feel. This thought must move beyond appeals to authority to legitimize its guiding ideas. Moreover, Western military thinking must not fall victim to emotionally reacting to flashy videos on social media to make claims about fundamental changes in war and warfare. Military thinking is far too serious a business to allow emotionally charged reactions to drive adaptations in doctrine and force structure.

Further, the principles of war are common property, meaning that they do not belong to a specific institution. An institution’s doctrinal definitions or modifications to the principles of war reflect the narrative that they want to advance their own military operations. Because the principles of war are common property, they are subject to refinement by the community of interest. Refinement that does not align with a military’s own modifications, such as offerings that do not align with the U.S. military’s modification of the principles of war to principles of joint operations, is valid. Moreover, when an institution modifies a common property idea to the point of fundamentally altering it, like the U.S. military did with the change from principles of war to principles of joint operations, they do gain ownership of that new concept. In addition, when an institution develops a new concept, like the U.S. Army’s Convergence or MDO, they own the idea. The difference here is that common property concepts can be modified by bottom-up change, whereas ideas that are proprietary can only be modified by the owner. As a result, common property ideas, like the principle of war, maneuver warfare and many others, should be vigorously debated within and outside military institutions.

In the case of war, conformity and uniformity, or patterned thinking, often prove disastrous. In that spirit, the principles of war introduced within this paper reflect the keen importance that system theory and determinism have on the actions of all the belligerents within a conflict. Moreover, the principles reflect war’s duality through the novel use of inverse principles to present each principle’s negative image and to illustrate its importance.

Lastly, all military thinking, whether it is common property or an institution’s original work, must be thoughtfully critiqued. Rigorously examining military concepts, doctrine, strategies and non-specific ideas is the method by which those ideas are improved. Improvement is not for improvement’s sake, but so that the forces using those ideas have a correct frame and a set of theoretical practices from which to draw when they are planning for and participating in conflict. To close, it is important to remember the words of Fuller. He cautioned: “Method creates doctrine, and a common doctrine is the cement which holds an army together. Though mud is better than no cement, we want the best cement, and we shall never get it unless we can analyze war scientifically and discover its values.”52

The collective community of interest must shake itself awake and move beyond the institutionally reinforcing and traditionalist thinking. The community of interest must take Fuller’s recommendation to thinking scientifically about war and warfare and provide detailed criticisms of where current military thinking is falling short. Otherwise, Western militaries could end up on the inverse side of winning.

The next article in this series will address principles for warfare and how to restructure the battlefield for future armed conflict. In doing so, the article will continue with the idea of principles and inverse principles. Moreover, the article will use the myths and principles of war from this article, the principles of warfare from the forthcoming article, novel technology estimates and potential threat tactics to provide a novel way to think about how to array and fight on the battlefield in the future.

★ ★ ★ ★

Amos Fox is a PhD candidate at the University of Reading and a freelance writer and conflict scholar writing for the Association of the United States Army. His research and writing focus on the theory of war and warfare, proxy war, future armed conflict, urban warfare, armored warfare and the Russo-Ukrainian War. Amos has published in RUSI Journal and Small Wars and Insurgencies among many other publications, and he has been a guest on numerous podcasts, including Royal United Services Institute’s Western Way of War, This Means War, the Dead Prussian Podcast and the Voices of War.

- B.H. Liddell Hart, The Ghost of Napoleon (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1934), 110–111.

- Franz-Stefan Gady, “What if the Deep Battle Doesn’t Matter?” Peter Roberts (host), This Means War (podcast), 14 September 2023.

- See Cathal Nolan, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) and Anthony King, Urban Warfare in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, England: Polity, 2021).

- B.H. Liddell Hart, The Ghost of Napoleon (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1934), 114–115.

- Milford Beagle, Jason Slider and Matthew Arrol, “The Graveyard of Command Posts: What Chornobaivka Should Teach Us about command and Control in Large Scale Combat Operations,” Military Review 103, no. 3 (2023).

- Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military Campaigns (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006): 86–89.

- Amos Fox and Thomas Kopsch, “Moving Beyond Mechanical Metaphors: Debunking the Applicability of Centers of Gravity in 21st Century Warfare,” Strategy Bridge, 2 June 2017.

- David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (London: Scribner, 1973), 413.

- Jurgen Brauer and Hubert Van Tuyll, Castles, Battles, and Bombs: How Economics Explains Military History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 131.

- Mark Landler, “20 Years On, the War on Terror Grinds Along, With No End in Sight,” New York Times, 10 September 2021; Jeff Seldin, “Death of Islamic State Leader Not Seen as Diminishing Long Term Threat,” VOA News, 9 August 2023.

- Julian Barnes, Helene Cooper and Eric Schmitt, “US Intelligence is Helping Ukraine Kill Russian Generals, Officials Say,” New York Times, 4 May 2022; David Martin, “Gen. Mark Milley on Seeing Through the Fog of War in Ukraine,” CBS News, 10 September 2023.

- Editorial Board, “How Ukraine Can Break the Stalemate,” Washington Post, 12 November 2023.