Maneuver and Breakthrough in 1940 France: Insights for the U.S. Army and the Russo-Ukrainian War

Maneuver and Breakthrough in 1940 France: Insights for the U.S. Army and the Russo-Ukrainian War

by LTC Nathan A. Jennings, PhD, USA

Land Warfare Paper 156, January 2024

An earlier version of this paper was published in April 2022: Considering the Penetration Division: Implications for Multi-Domain Operations, Land Warfare Paper 145. Due to significant development in this arena that has arisen out of the current Russo-Ukrainian War, this updated and more relevant version appears here.

In Brief

- This essay employs a historical examination of German operational maneuver in the 1940 Battle of France to explore the arrayment of asymmetric advantages required to conduct such a high-risk and high-reward mission with particular focus on the hardest maneuver task: operational penetration at scale.

- For the Germans, the study finds that, in addition to novel combined-arms restructuring, the Wehrmacht’s prioritization of tactical ground mobility, dedicated air interdiction, tailored sustainment, integrated operational design, credible military deception and a nested operational approach allowed them to attain fleeting and decisive advantage over the French and British defenders.

- This is relevant to the U.S. Army as it reorganizes tactical echelons and adopts Multi-Domain Operations in order to execute future offensive campaigns that may require assertive operational maneuver—even as conflicts in Ukraine and Nagorno-Karabakh indicate that positional and attritional trends are increasingly defining the strategic environment.

Introduction

Following two decades of expansive counterinsurgency and counterterrorism campaigns across the Middle East, the U.S. Army is embracing Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) as a new battle doctrine to counter and defeat peer competitors in larger-scale confrontations in the 21st century. The seminal transition, which is evolving in the shadow of a costly Ukraine conflict where defensive fires are dramatically challenging offensive maneuver, includes structural emphasis on empowering theater armies to converge joint and multinational capabilities, optimizing corps to integrate multi-domain efforts, and functionalizing divisions to conduct cross-domain operations with enhanced capabilities. The modernization initiative will enable the landpower institution, as required by General Charles Q. Brown Jr., the 21st Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to “fight today’s battles but also to prepare for tomorrow’s wars” while “aggressively leading with new concepts and approaches.”1

As part of the effort to create an echeloned force that is optimized for combat at scale—as opposed to the brigade-centric order of battle that fought in Iraq and Afghanistan—the Army is developing MDO-capable divisions to serve as the primary unit of action and to provide senior commands with potential to execute among the most challenging of combat actions: operational penetration with intent to inflict systemic disruption or even collapse across rear areas. Representing the “sum of the Army’s thinking about large-scale combat operations,” as argued by its Combined Arms Center, the new formations will enjoy enhanced tactical profiles to “conduct the joint force’s most demanding operations” that include the breaching of fortified lines and execution of contested-gap crossings—all despite robust evidence of an increasingly lethal paradigm that has created attritional nightmares for both Russian and Ukrainian forces in scorched places such as Bakhmut, Vuhledar, Zaporizhzhia and Avdiivka.2

This focus on developing more agile formations with echeloned fires, reconnaissance, engineering, informational and sustainment assets in order to bridge the tactical and operational levels of war represents not only structural modernization, but a conceptual shift to provide senior commands with the ability to fight through integrated fires defenses where swarming drones, ubiquitous surveillance and precision strike are disaggregating traditional combined arms approaches. Recognizing the enduring requirement to disintegrate, dislocate and exploit sophisticated area denial architectures in expeditionary settings, the new order of battle—best represented by dramatically enhanced armored divisions—provides U.S.-led coalitions with the premier capability to counter the attritional and positional trends that are defining warfare on the battlefields of Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine.3

The adoption of new approaches to enable multi-domain maneuver, which includes redesigns for airborne divisions to achieve joint forcible entry, holds foundational implications for American force projection. Typically representing both a high risk and high reward endeavor that requires arrayed asymmetric advantages to extend operational reach, the Army’s divisional modernization holds the potential to empower, or conversely limit, landpower capacity to achieve decisive outcomes. Taking a longer view of military history, it represents a continuance of an American way of war that prizes firepower and technology to negate the maelstroms that have inflicted massive destruction and casualties across the farming landscapes and industrial zones of the Ukrainian steppes.4 In this context, analysis begins with the theory behind the concept, and then follows with a historical example that, against all odds, achieved ahistoric success: the German invasion of France in 1940.

Theoretical and Historical Context

The concept of employing mobile ground forces with high-end capability to penetrate an enemy’s prepared front and breakout into more vulnerable rear areas is not a new idea. Armies operate as complicated, interdependent systems that rely on cohesion and synchronization to succeed; recognizing this, combined arms formations have historically conducted relatively narrow, operationally deep attacks through breaches, gaps or seams—along an extended enemy front—to strike at headquarters, lines of communication, logistics nodes and rear echelons, physically dislocating and psychologically fracturing the opposing force. The maneuver, which encompasses a tactical theory of victory that prioritizes speed and shock action to win decisively while avoiding longer attritional fights that typify most conflicts, represents a complicated scheme that can be extremely difficult to execute.5

Despite the aspirational benefits, the very nature of the penetration form of maneuver creates enormous peril for the attacking army as increasing success incurs higher degrees of risk. The deep attack along a relatively narrow axis means that assaulting elements may be vulnerable to counterattacks along their ever-extending flanks, and that they must possess the operational reach and striking power to attack enemy centers of gravity, or equivalent points of vulnerabilities, that will catalyze systemic confusion or degradation. Furthermore, the leading forces must attack with requisite speed, provisions, gap-crossing ability and shock effect to advance within the enemy command’s decision cycle. This can prevent recovery and counterattack before follow-on echelons can exploit, as described by MDO doctrine, the “windows of superiority” created by the sudden disruption in adversary cohesion.6

The challenges of a successful penetration attack reveal why, throughout history, most generals have aimed for, as described by British theorist Liddell Hart, a more “indirect approach” to winning decisively that avoids the potential for shattering losses that often result from matching strength against strength.7 Often arriving as a flank or envelopment maneuver that relies on circuitous movement to avoid costly frontal assaults—which became more and more costly with the industrialization of warfare during the 19th and 20th centuries, renowned commanders such as Hannibal the Great, Frederick the Great, Helmuth von Moltke, Ulysses Grant, George Patton and Norman Schwarzkopf each achieved seminal victories by mastering an encircling approach. Where Hannibal’s double-envelopment of the Romans at Cannae in 216 BCE exemplified the ideal for a millennium, Schwarzkopf’s routing of the Iraqi Army in 1991 serves as a more recent manifestation.

However, despite the incurred risks, some of history’s most effective commanders have still employed the penetration form of maneuver, expanded in scope and scale beyond mere tactical effect, to achieve decision. A brief survey includes: Alexander the Great’s employment of massed heavy cavalry to strike the command and control of a much larger Persian army at Gaugamela in 331 BCE; Napoleon Bonaparte’s shattering of a combined Austrian-Russian army at Austerlitz with an exquisitely timed center assault that fatally fractured the coalition’s cohesion in 1806; and, to a more limited extent, the Allied mechanized attack at Amiens in 1918 that broke the German Army in the final year of World War I. In each of these examples, the victorious force employed a deep attack along a relatively narrow axis to strike critical elements in a surprised enemy’s rear area, ultimately causing a cascading disintegration of their physical and psychological capacity to fight as combined-arms entities.

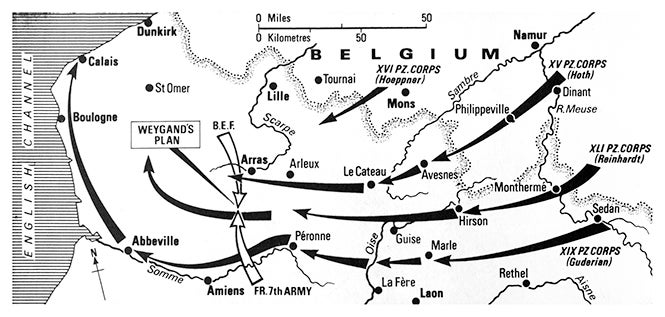

Yet of all the successful penetration attacks in history, perhaps none balanced fire, maneuver and risk at the operational level with greater effect than Panzer Group Kliest in particular, and the German Army in general, at the Battle of France in 1940. Unfolding as one of the pivotal moments of World War II, the Germans shifted to a hastily adopted plan at the onset of conflict that was designed to fix the main Anglo-French armies in the north along the Belgian frontier while attacking with massed Panzer divisions and air interdiction in the theater center. The offensive, which would come to be known as Blitzkrieg, or “lightning war,” due to the unprecedented speed, shock and depth of the joint and combined arms assaults, aimed to avoid a repeat of the attritional horrors of World War I by combining fast-moving armor with dedicated air strikes in order to achieve operational breakthrough at a seam just north of the vaunted Maginot Line.8

Figure 1: Panzer Corps' Advance During the Battle of France

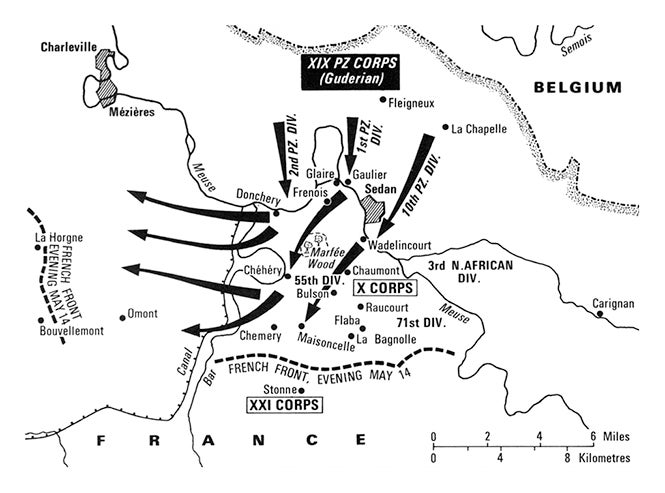

The critical action of the extraordinarily risky German offensive proved to be Panzer Group Kleist’s attack near Sedan, which required a contested crossing of the Meuse River with two panzer and one motorized infantry corps. With the XIX Panzer Corps under Heinz Guderian in the lead, the Germans emerged from the seemingly impassible Ardennes forest and forced several precarious—and almost denied—gap crossings to seize footholds in French territory. Then, against all conventional practices that required the attackers to pause to bring up massive artillery trains, and benefiting from the novel mobility of the Panzer divisions, the invaders risked an immediate advance toward the English Channel as the French struggled to comprehend and contain the breakout. Stemming from a combination of German audacity, French missed opportunities, and even sheer luck, the Wehrmacht had seized a scope of operational initiative heretofore thought impossible by World War I standards.9

Figure 2: Battle of Sedan

The breakout at Sedan set conditions for the dislocation of France’s entire strategic defense and the disintegration of Anglo-French cooperation from the center outward. Sensing the French Army’s collapsing cohesion and failure to launch meaningful counterattacks against their exposed flanks, Panzer Group Kliest, named for its commander, Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist, attacked northwest toward the Channel ports along an increasingly precarious axis, with intent to cut across the rear of the powerful Allied armies that had marched into Belgium to counter the assumed German main effort. The resulting race to the sea, which Guderian misleadingly reported as a “reconnaissance in force” when his higher command ordered him to halt over concerns of imminent culmination, isolated the most effective Allied forces at minimal cost while catalyzing despair across French senior leadership.

The elimination of opposition in Belgium set conditions for a reorientation of the entire German Army to the south to reduce the remainder of the French defenses. Executing a series of penetration and exploitations as the French attempted to reform several lines of resistance, the resulting total defeat of France and humiliation of Great Britain shocked the world. Yet, while the massing of armor had proved central to German success, the “lightning” maneuvers could not have succeeded without two additional factors: the novel employment of radios that allowed communication between attacking elements, and, perhaps more important, the Stuka Dive Bombers that provided fires, or “vertical artillery,” to shape conditions for advancement. These two innovations, as much as the German predilection for decentralized initiative, provided critical asymmetric advantages that enabled the invaders to deflect French counterattacks, avoid attritional losses and prevent culmination.10

Arraying Asymmetric Advantages

Similar to the advent of German Blitzkrieg as an emerging operational concept in the early years of World War II, the contemporary U.S. Army’s adoption of a modernized force structure with greater fire and maneuver capacity represents a multi-domain solution to the attritional and positional contests that seem to be increasingly defining warfare in the 21st century. As argued by General George Randy, the 41st Chief of Staff of the Army, it reflects the next step in the landpower institution’s ever-evolving mandate to “confront emerging battlefield dynamics” and maintain “competitive advantage over potential adversaries” while embracing the imperative to “rapidly incorporate promising technology into the force.”11 By enhancing its ability to execute decisive maneuver, the Army is once again aligning its form, function and purpose against the predictable requirement to achieve unambiguous victory in the most challenging circumstances.

This move toward enabling more audacious and risky operational approaches consequently requires examination of both theoretical and historical insights from past experiences. First, at the most basic tactical level, pattern analysis of previous large-scale attempts at operational penetration indicate that corps and divisions must possesses a premium mobility and internal capacity to complete deeper attacks into enemy rear areas. While protection and firepower remain critical, especially in armored combat, the capacity to sustain an accelerated rate of march—exemplified by Guderian’s lightning attack to the Channel—allows the attacker to seize initiative within the adversary decision cycle. The imperative to continue advancement, despite the ever-increasing risk of culmination and flank exposure, creates multi-faceted dilemmas for the defenders as cohesion begins to fracture.12

The requirement for tactical mobility includes the timeless mandate to execute contested gap crossing operations under the most adverse circumstances imaginable. River systems, similar to the Dnieper River basin that has severely impeded ground offensives for both combatants in Ukraine, present one of the key obstacles that can slow or deny the execution of a rapid and narrow advance, especially when overwatched by a prepared defense-in-depth with fortifications and ranged fires. Similar to Guderian’s precarious crossing over the Meuse—which initially proved a desperate affair as his three Panzer divisions struggled to establish footholds—failure at the point of crossing, for any reason, can slow or stymie the main effort of the attack. The resulting risk to mission suggests that corps, field armies and joint force commands must exactingly synchronize deep fires, engineer assets and sequenced assault elements to ensure continued rates of advancement for assaulting ground elements.13

The second critical factor for successful operational maneuver is the necessity of assured tactical sustainment. Because its ever-elongating lines of communication will be vulnerable to disruption by enemy attacks, inclement weather, adverse terrain and discoordination, attacking corps and divisions may need to carry most of their fuel, ammunition and provisions in organic trains to ensure continued rate of march while avoiding culmination. In the case of Panzer Group Kleist’s penetration at Sedan in 1940, the German high command reinforced its organic logistical trains with three additional motor transport detachments for an additional 4,800 tons of carried supplies. The result was that Guderian’s Panzer corps attacked all the way to Calais on the French coast with few, if any, significant sustainment interruptions that were not negotiated and ameliorated within the group.14

This requirement to continuously extend ground operational reach creates significant dilemmas for the contemporary U.S. Army. Already posing significant challenges for its armored brigades and heavy divisions due to extraordinarily high consumption requirements, the penetration elements’ demand for vast quantities of fuel, ammunition, durables and provisions will multiply the problems of projecting sustainment along rapidly extending lines of communication. Similar to the German logistical solution for Panzer Group Kleist in 1940, the Army’s attacking formations will likely be required to carry much of their required supply to avoid interruption or culmination at critical moments. This may include, as evidenced in the Russo-Ukrainian War, dramatically accelerated consumption of tank and artillery ammunition that exhausts forward magazines and stresses theater distribution capacity.15

The third lesson moves beyond tactical considerations and into the operational design that forms the conceptual foundation of operational art. Analysis of successful large-scale maneuvers reveals that it is not sufficient just to have a mobile and sustained attack formation; the idea must be integrated within a larger, coherent operational concept that capitalizes across all domains and dimensions of warfare to create inescapable dilemmas for the enemy command. Furthermore, as exemplified by the German innovation of employing dive bombers to shape favorable maneuver conditions for the advancing panzers, any concept built around operational penetration, in particular, must possess meaningful asymmetric offsets across other combat arms, services or domains. This is an essential requirement to provide enough time and space for the ground assault to achieve the depth of advance required to systemically and physiologically dislocate the enemy command.16

This requirement means, for the U.S. Army, that the new maneuver capabilities must develop within the evolution of MDO as a mature operational concept with complimentary modernization programs. Just as the Germans combined tactical communication and air power to shape conditions for the ground advance, the U.S. Army must fully leverage internetworked fires from across land, air, maritime, cyber and space domains—even as it operationalizes emergent technologies such as artificial intelligence, autonomous robotics, hyper-ranged weapons, drone technologies, and electronic warfare and space capabilities—to create synchronized windows of superiority.17 The rapidity of the penetration, which may require the bypassing of enemy strongpoints, will likewise compel Mission Command philosophy by senior commanders in order to maintain planned rates of advance and to prevent disruption.

A fourth consideration, which also relates to operational design, is the aim point or objective of the deep attack in relation to enemy structure and vulnerabilities. While some historical examples, such as Alexander the Great’s cavalry charge at Gaugamela, achieved success by striking an identified center of gravity such as a command-and-control node, others, including the German Army in the Battle of France, have employed the arc of the penetration to attack critical vulnerabilities and to isolate specific enemy forces in order to cause physical and psychological collapse across the broader adversary institutions. In the latter example, the German deception plan worked perfectly to lure the most capable Allied field armies into Belgium, where they presented German Army Group A with the opportunity to maneuver behind them, to sever their vital lines of communication back to the French support areas and to convince national leaders in Paris that strategic defeat had become inevitable.18

This kind of precise aim for the breach and breakthrough naturally requires an exquisite understanding of the adversary’s operational center of gravity, political situation and psychological dependencies to enable accurate campaign design. For the U.S. Army, as it develops its MDO concept, it means that ground maneuver must both leverage, and sometimes enable, joint fires, multinational capabilities and interagency effects that seek to dis-integrate enemy defensive networks by striking or isolating key elements to create fatal disruptions and cognitive confusion. Usually featuring targets located in the enemy rear area, systemic fracturing will infect and confuse frontline combat forces; the application of advanced operational art, unfolding within specific political and social contexts, provides an avenue by which to avoid the bloodletting and destruction that often occurs when militaries engage in such symmetrical clashes as are exemplified by the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War.19

A fifth consideration, which also relates to operational design, centers on the provision of operational deception to create advantageous conditions for maneuvering forces to achieve their distant objective. Historically, winning commanders have arranged tactical actions to specifically deceive enemy forces as to actual intent for a center assault, or to entice the opposing force to dilute combat power at a critical seam or breaching point along the front. While the Macedonians at Gaugamela enticed the Persian cavalry to overextend its line with an enveloping feint, and Napoleon intentionally left his right flank weakened at Austerlitz to entice the Russians to move forces from their center to attempt an envelopment, the Germans likewise deceived the French in 1940 into believing that their main effort was attacking through Belgium instead of at Sedan.20

This requirement will likely prove even more critical to achieving operational penetration on the increasingly transparent battlefields of the 21st century. While future deceptions will combine traditional offensive and defensive ground force arrangements with emergent electronic, informational and political warfare schemes, the purpose will remain the same: to mask friendly intent and to entice the adversary into unintentionally revealing or providing some kind of entry point and avenue for the attacking force to strike a debilitating aspect of the enemy center of gravity.21 Just as in previous eras, successful deception, which has proved extraordinarily challenging in Ukraine due to pervasive surveillance technologies, will require commanders to develop a measure of coup d’œil, or operational intuition, to acquire a timely and accurate understanding of battlefield terrain, enemy intentions, cultural predilections and systemic weaknesses to create favorable conditions for the actually intended scheme of maneuver.22

A final insight for the implementation of operational penetration, at scale, considers how the tactical action relates to military strategy. As a discreet operational approach selected from the available forms of maneuver, the potential employment of this exceptionally precise echelonment within a new battle concept such as MDO—whether as an ad hoc device or within a planned framework—offers both high risk and high reward for prospects of strategic success. While on one hand the spatial geometry of breach and breakout incurs risk of early culmination due to numerous aspects of Clausewitzian friction that could stall the advance, on the other hand, it arguably offers an expeditionary force with an avenue by which to achieve a Jominian decisive victory with the least amount of casualties. If the former demands rational analysis of probabilities and enemy intention, the latter remains an attractive, if high risk and sometimes improbable, option for sophisticated armies to win efficiently and rapidly in expeditionary settings.

This question of strategic utility, and balancing of strategic risk and reward, means that the integration of revitalized maneuver designs must ultimately lead to battle outcomes that position American-led coalitions to attain, as described by air power theorist Everett Dolman, a “position of continuing advantage.”23 As an emergent factor in how future operational art will connect evolving strategy and modernizing tactics across increasingly lethal and transparent battlefields that deny the advantage of surprise, the cultivation of operational maneuver as a foundational element of the U.S. Army’s theory of victory will have systemic and cultural implications for how it participates in the American way of war. Recognition of these factors becomes especially acute given the nuclear context of great power confrontation, and how the evolution of the MDO doctrine will both challenge and accommodate the current strategic paradigm in relation to peer adversary tolerances.24

Conclusion: Insights for Operational Maneuver

In the final analysis, as articulated in the U.S. Army’s own vision for transformation, the institution must modernize in order to “prevail from competition through conflict with a calibrated force posture of multi-domain capabilities” that “provide overmatch through speed and range at the point of need.”25 This means that it must be prepared to innovate with new manifestations of maneuver warfare that will allow it to avoid, or negate, the attritional and positional trends that have caused frustration and exhaustion across the steppes of Ukraine. While the Germans developed a panoply of intentional, incidental and accidental asymmetries that allowed them to penetrate and exploit the most imposing defensive construct of their era, U.S.-led coalitions will have to apply similar degrees of novelty and adaptation to negotiate the lethality of the current military environment where swarming drones, ubiquitous surveillance and precision strikes are wreaking havoc on combined-arms offensives.

However, despite the manifest value of unleashing operational maneuver to win with decision, such a conditional approach should be assessed within the stark reality that it remains an extremely risky undertaking with only the most conditional of applications. Even as American political culture will continue to demand rapid and definitive outcomes in expeditionary campaigns featuring limited mobilization and accelerated tempos, military leaders will need to plan and advise with probity and caution, lest they rush to emulate the tragedies unfolding across the battlefields of the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. For every successful Battle of France that enjoyed a unique cascade of asymmetric advantages within fleeting military and political conditions, there are numerous examples—exemplified by the “tank graveyards” of Zaporizhzhia and Avdiivka—where large-scale ground assaults shattered themselves against defenses primed with fortifications, counterattacks and integrated fires.26

This means that any force attempting to maneuver at-depth must be clear-eyed about the wishful thinking and faulty information that can create the idealized perception, as opposed to the evidence-based reality, of the imposing arrayment of offsets and advantages required to accomplish among the hardest tasks in warfare. For the U.S. Army, as it modernizes to adopt new structures and concepts, it suggests that any decision to execute offensives in the face of industrial and nationalistic resistance must be accompanied by optimizations that include premium mobility, enhanced sustainment, effective deception and insightful operational design—all in support of operational approaches and theater strategies that cultivate conditions for success. If a concerted focus on large-scale maneuver provides a potential pathway for American forces to win decisively on foreign ground, the challenges of accomplishing such a high-risk and high-reward endeavor should invite equal humility and caution.

★ ★ ★ ★

Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Jennings is an Army Strategist and Associate Professor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, KS. With a background in armored warfare, he served multiple combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, is a graduate of the School of Advanced Military Studies, and he holds a PhD in History from the University of Kent.

- General Charles Q. Brown Jr., Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Message to the Joint Force,” Washington, DC, 2 October 2023.

- “WayPoint in 2028 – Multidomain Operations,” U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, 3 December 2021, video, 14:00; Shashank Joshi, “The war in Ukraine may be heading for stalemate,” The Economist, 13 November 2023.

- Field Manual (FM) 3-90-1, Offense and Defense Volume 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, March 2013), 1-3.

- Colin Gray, “The American Way of War,” in Rethinking the Principles of War, ed. Anthony D. McIvor (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2005), 30–33; Seth Jones, Riley McCabe and Alexander Palmer, “Seizing the Initiative in Ukraine: Waging War in a Defense Dominant World,” Center for Strategic & International Studies Brief, 12 October 2023.

- FM 3-90-1, 1-3.

- U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028 (Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, 6 December 2018), 20.

- B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy, 2nd ed. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1968), 17.

- Karl-Heinz Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France, 1940,” in Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, eds. Michael D. Krause and R. Cody Phillips (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2005), 169–179.

- Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France, 1940,” 172–174.

- Williamson Murray, “May 1940: Contingency and fragility of the German RMA,” in The Dynamics of Military Revolution, 1300-2050, eds. MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 162–163.

- General Randy George, Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Statement to the Subcommittee on Armed Services, United States House of Representatives, First Session, 118th Congress, 9 April 2023.

- TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, 7–8.

- FM 3-90-1, 1-32.

- Karl-Heinz Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France, 1940,” 170–171.

- FM 4-0, Sustainment Operations (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, July 2019), 7-1.

- FM 4-0, 177–178.

- Nathan Jennings and Adam Taliaferro, “Tempo, Cohesion, and Risk: Towards a Theory of Multi-Domain Warfare,” Wavell Room, 18 June 2021.

- Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France, 1940,” 178–179.

- Jennings and Taliaferro, “Tempo, Cohesion, and Risk.”

- Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France, 1940,” 171–172.

- Christopher Rein, “Weaving the Tangled Web: Military Deception in Large-Scale Combat Operations,” Military Review (September–October, 2018): 11.

- William Duggan, “Coup D’oeil: Strategic Intuition in Army Planning,” Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, November, 2005.

- Everett Dolman, Pure Strategy: Power and Principle in the Information and Space Age (London: Frank Cass, 2005), 26.

- Jasmin J. Diab, “Nuclear Strategy,” in On Strategy: A Primer, ed. Nathan Finney (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2020), 193–194.

- General James C. McConville, Army Multi-Domain Transformation: Ready to Win in Competition and Conflict, Headquarters, Department of the Army, 16 March 2021, 1.

- Seth Jones, “Seizing the Initiative in Ukraine,” CSIS Brief, 12 October 2023.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.