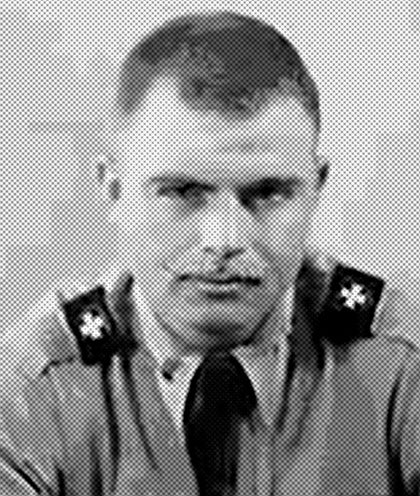

The first time I met him, Col. Walter Ballard Clark scared the hell out of me. He wasn’t a big man. In fact, he stood well under 6 feet tall. Yet he was crew cut and ramrod straight. A wiry, intense guy, he had eyes that could burn holes in you like two laser beams, and he was blessed with a classic command voice. He was the commandant of cadets at The Citadel, the Military College of South Carolina in Charleston. Although the college featured a dignified, distant, three-star general as its president, for some 2,000 cadets, Clark, of The Citadel’s Class of 1951, embodied the rod of iron. Discipline mattered. He imposed it.

I was nobody, maybe subnobody. I came from Illinois—the Land of Lincoln on my driver’s license—and now I stood in the middle of all of these Southerners at their ersatz West Point, wondering what I’d gotten myself into in August of 1974. When a big cadet sergeant, a junior, asked me “who won the war,” I thought he meant Vietnam. But he meant the Big One, that one in 1861–65. Being a guy from Illinois, I invariably gave the right answer, which in that time and place was very much the wrong answer. I did a lot of pushups that summer.

Clark’s duties kept him busy far from the day-to-day squalor of squad sergeants and buzz-cut “knob” freshmen like me. But I came to The Citadel with an Army ROTC scholarship, and Clark also served as the professor of military science. So, when faculty members drew names to “sponsor” newly arrived knobs, Clark got me. Along with three other knobs, I dutifully made my one (and only) trip to his stately Charleston home. I drank the iced tea, ate the fried chicken and kept my mouth shut. The colonel might have been able to pick me out of a police lineup thereafter … if I wore a name tag.

Policy of Avoidance

I studiously avoided the colonel for the next four years. He inspected my room one Saturday in my sophomore year. I got demerits. No miscue ever escaped his piercing gaze.

My senior year, Clark retired. I congratulated myself on having had little to do with him. I respected the colonel, of course. All the cadets knew that as an infantry lieutenant in the Korean War, he’d been badly wounded and earned a Silver Star leading his troops in an attack on a Chinese bunker complex. The colonel commanded an infantry battalion stateside in 1967–68 and had the sad duty of deploying to Chicago to quell riots. Just before reporting to The Citadel, Clark had served as the province senior adviser in Vinh Binh, South Vietnam. That country no longer existed by the time I graduated from The Citadel in 1978.

There things might have remained had it not been for my future wife. A Southerner herself, she attended college in Charleston and met Clark at a formal dance at The Citadel. When I drove up from Fort Stewart, Georgia, one weekend, she suggested we pay a call on Clark and his gracious wife, Ellen. I wasn’t so sure. But she was. As usual, she got it right.

Newfound Understanding

From that day in early 1980 until his death in 2010, I got to know the Clark I had ducked during my cadet days. No infantry officer could ever ask for a better mentor, although I don’t think I had ever heard that term except in reference to an obscure character in Greek mythology. My father was a wartime infantry sergeant in Korea. By his own admission, he didn’t know, or want to know, anything about officer stuff.

Clark spent endless hours educating me on how the U.S. Army really worked, the stuff not in the field manuals or the slide decks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He’d been the aide to Maj. Gen. Joseph Harper, the World War II commander of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment at Bastogne, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944–45. When I later served in the 1st Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, Clark came and spoke to us about what Harper had taught him.

Clark also had been the senior aide to Gen. Charles Bonesteel III in Korea during the height of the 1966–69 fighting on the Demilitarized Zone, to include the North Korean seizure of the USS Pueblo and its crew. The colonel understood Korea very well. I served three times in the 2nd Infantry Division in Korea. Clark’s insights consistently paid off.

We exchanged books and articles of interest. The colonel knew more history than I did, and he steered me to learn more. Heritage matters, and the colonel was tickled when my son graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, as an armor officer—almost as good as infantry. The colonel’s two sons, both infantry and then special operators, served in the Army, and both fought with distinction in the years after 9/11.

Fond Memories

Being a tough old colonel of infantry, Clark didn’t have much use for most generals. He knew too many too well. Even so, he rejoiced when the Army promoted the likes of me to brigadier general. Who says the Army doesn’t have a sense of humor?

Clark died on May 29, 2010. In remembering the colonel, I have to agree with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, someone I don’t agree with much. Quoting a long-forgotten song, MacArthur told lawmakers on Capitol Hill in 1951: “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” Maybe so.

But if I have anything to say about it, Col. Walter Ballard Clark’s fade-out won’t happen anytime soon.

* * *

Lt. Gen. Daniel Bolger, U.S. Army retired, commanded soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is a senior fellow of the Association of the U.S. Army. His most recent book is The Panzer Killers: The Untold Story of a Fighting General and His Spearhead Tank Division’s Charge Into the Third Reich.