May 2018 Book Reviews

May 2018 Book Reviews

Soldier Embarks on a Marathon Recovery

Fighting Blind: A Green Beret’s Story of Extraordinary Courage. Ivan Castro and Jim DeFelice. St. Martin’s Press. 304 pages. $16.99

By Maj. Jason P. LeVay

Retired Maj. Ivan Castro is a celebrity in the world of triumph over adversity. Famous for running marathons as a blind man, this book satisfies the intense curiosity surrounding Castro’s story. With the help of co-writer Jim DeFelice, he describes a familiar yet discreet American soldier story.

Growing up in a small town in Puerto Rico, Castro didn’t particularly stand out, muddling his way through school looking for direction and meaning. Time in Junior ROTC and ROTC led him to a life in the military. He loved being a soldier, and then when life directed him to the officer ranks, he loved leading soldiers. Eventually, like happens to too many young men and women, combat took its toll on his body, his mind and his family.

As a youth, Castro found the ruggedness of country life rewarding. He admired education, but was athletic and preferred the outdoors or drilling with the JROTC, as it provided him discipline, direction and focus for his mental and physical energy. College seemed like the next logical step, and he funded his way with a track scholarship. However, college did not satisfy him, and when he realized he was most happy competing in track or conducting ROTC training, he dropped out and enlisted.

He loved his new job and excelled as a soldier, NCO and then as a Special Forces soldier. Along the way he fell in love. After a training injury, he finished his remaining college requirements and applied to Officer Candidate School to better provide for his family and revisit a past desire.

While leading a scout platoon in Iraq, a mortar attack killed two of his soldiers, nearly killed him and left him blind. This was a tremendous blow and to someone who was as physically active as Castro, it was psychologically crippling. Used to exerting his will over his environment, he pushed himself through his rehabilitation with astonishing speed, hard work and extreme dedication.

A goal-oriented man with a magnetic personality, he asked friends to help him train for cross-country cycling and eventually for a marathon. This created a splash in the wounded soldier community and in special operations, which went out of its way to allow him to stay in the Army.

However, his trials through recovery did cause other wounds. His wife found the emotional cost too difficult and broke his heart when she left him. Despite his heartache, he moved on and eventually found love again.

Interspersed throughout this story are interludes of a 2013 Walking With The Wounded charity expedition to the South Pole with Prince Harry. The writers hope the reader draws parallels from these interludes with phases of Castro’s life, but it would have been better served as its own section.

This book offers those who have never served in the military a look at a near-ubiquitous background story of a Special Forces soldier. It will also inform junior enlisted soldiers who are thinking of pursuing a career in Special Forces.

Everyone who reads this book will see the toll that crippling injuries can cause even people of strong character. Those same people will also be inspired by how something as terrible as being blinded can lead to positive outcomes and a rewarding life. Castro shows himself to be a deep, reflective and uplifting person whose story is worth telling.

Maj. Jason P. LeVay has served in infantry, Special Forces and Ranger units over the past 27 years. He holds a master’s degree in history from Yale University and teaches at the U.S. Military Academy.

* * *

Army General’s Career Soars

Architect of Air Power: General Laurence S. Kuter and the Birth of the US Air Force. Brian D. Laslie. University Press of Kentucky (An AUSA Title). 254 pages. $39.95

By Bill Yenne

Laurence S. Kuter is one of those people who seemed to have been everywhere, and to a large extent, he was.

In reading and writing about the strategic organization and direction of American air power in World War II, I have come across Kuter’s name and his contributions innumerable times, so it is exciting to be able to read this excellent biography. In the critical year and a half on the cusp of American entry into the war, he was part of that amazing brain trust that formed around Hap Arnold—men such as Tooey Spaatz, Ira Eaker, Hal George, Haywood Hansell and others—the architects who formulated an ultimately successful strategy for the deployment of air power to win a global war.

While Arnold, Spaatz and Eaker are household words in air power circles, Kuter appears almost as a supporting character in their narratives. In Architect of Air Power, Brian D. Laslie writes, “One of Kuter’s traits was the ability to keep the spotlight off of himself.”

Thanks to Laslie, who is deputy command historian at the North American Air Defense Command and the U.S. Northern Command as well as adjunct professor at the U.S. Air Force Academy, the spotlight has shifted. We not only have Kuter’s World War II accomplishments in context for the first time, but we have a full picture of the rest of his long and eventful career.

He graduated from West Point in 1927 into an Army in transition. The officers who would lead the service in the coming global conflict were then young officers on the move and many of them, like Kuter in 1929, were moving into the Army Air Corps. As Laslie explains, Kuter was at the Air Corps Tactical School in its formative years when air power doctrine was still being sketched on reasonably clean sheets of paper. He reached Washington, D.C., in 1939 on the eve of World War II, and when the autonomous U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) was created in 1941, he had a seat on the new Air Staff. More important, he had a seat on the Air War Plans Division, where he had a hand in forming strategic policy.

The demands of World War II put most of the officers at the head of the USAAF onto career paths that led them into combat commands. The fact that Kuter’s led him into staff positions and deputy commands also led him into obscurity when combat histories were written. Laslie puts Kuter’s career into context, following him through a series of important posts from England to the Mediterranean to the Pacific. Laslie takes us along as Kuter circumnavigates the globe, visiting perhaps more USAAF locations than any of his colleagues.

Kuter’s knowledge of the Allies’ top-secret Ultra code-breaking program prevented him from flying in combat for fear of his being captured, but lest we are led to believe this diminished his importance to the strategic effort, Laslie reminds us that it did not. In 1944, he was Arnold’s eyes over the Normandy invasion beaches on D-Day, flying high above in a B-17 bomber, watching the unfolding action. In 1945, he was Arnold’s eyes and ears at the milestone Yalta Conference, a major general in rooms filled with field marshals.

Biographies of so many of the great leaders of World War II end with the war’s end. Not so Kuter’s story. As he seemed to be everywhere during the war, he was the architect of so many of the institutions of the new and independent postwar Air Force. Kuter was essentially the founding father of Air University, and immediately after the war, he took over and revamped the Air Transport Command. He built it into the joint service Military Air Transport Service, which was essentially the world’s most expansive international airline. Along the way, he served as the first American representative to the new International Civil Aviation Organization, which is still the governing body of global air navigation.

Wearing four stars after 1955, Kuter commanded the Far East Air Force and Pacific Air Forces, and was the architect of their merger. He took charge of the North American Air Defense Command in 1959 and in this post, he helped develop the Cheyenne Mountain Complex project and exceeded Mach 2 in the back seat of an F-106.

This book is an essential look at perhaps the most important quarter-century in the history of air power development through the eyes and career of a man who saw and experienced it from every angle.

Laslie notes that Kuter’s temperament suited him for the roles in which he was cast. He writes that “even though he had to routinely and forcibly argue with officers senior to him in both rank and age, there is no account of Kuter ever losing his cool or his temper. Perhaps this is another reason he is so often overlooked; his self-control does not make for great writing.”

In this case, Laslie is wrong. It does make for great writing—and reading.

Bill Yenne is the author of numerous books on military and aviation history, including Hap Arnold: The General Who Invented the U.S. Air Force.

* * *

Superspy Did Not Slink in the Shadows

The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam. Max Boot. Liveright Publishing. 713 pages. $35

By Mark Bowden

In the summer of 1968, after Gen. William Westmoreland was removed as commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, Edward Lansdale had some advice for his successor, Gen. Creighton Abrams.

It was Westmoreland’s custom to arrive for regular consultations with South Vietnam’s top military commander, Gen. Cao Van Vien, “in the manner of a head of state,” Max Boot writes, “in his sedan accompanied by a flotilla of motorcycle outriders and a truckload of bodyguards. Vien, in turn, would be waiting to receive him with an honor guard.” Thus were these sessions reduced to ceremonial ritual, with each commander telling the other what he wished to hear.

“Do you drive?” Lansdale asked Abrams.

“Of course I do,” said the new American commander.

“So why don’t you go over in a jeep and take an aide if you want,” Lansdale suggested. “Be a human being. … Maybe you can help each other a bit. … It’s about time we got this thing on the basis of human beings talking to each other.”

And there you have the essence of CIA superspook, Air Force general, counterinsurgency expert Lansdale’s approach to low-intensity conflict, according to this absorbing, well-researched and important biography. Initially commissioned as an Army lieutenant in 1943, Lansdale is perhaps the most misunderstood American military figure of the 20th century. Boot demystifies him here, showing him to be at heart an idealist, but also a man of deep contradictions in his personal and professional life.

Lansdale emerges as a charming, creative, daring and amazingly effective man, whose work ranged from profound success in the post-World War II Philippines, to aborted promise in Vietnam, to the sheer folly of John F. Kennedy administration efforts to overthrow or assassinate Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

Boot suggests that if America had chosen to heed Lansdale’s advice instead of dumping South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and cranking up its war machine, it might not have suffered such a humiliating defeat in Vietnam, and in later years may have avoided the ongoing slow-motion disasters in Iraq and Afghanistan.

An ad man from California with a World War II background in the CIA’s precursor agency, the Office of Strategic Services, Lansdale was perhaps the least likely person to become the most famous of America’s secret warriors. For one thing, he was the most open of spies. He had no patience for traditional tradecraft and had a gift for using information to further strategic goals. Utterly free of racism and superpower arrogance, respectful, curious and caring about the Asian people he sought to help, Lansdale succeeded mostly by being, as he put it, “a human being.”

In the Philippines, where he made his reputation, he first took pains to befriend politician Ramon Magsaysay, and only then helped steer him to power, crushing a communist insurgency and erecting an enduring popular government and American ally.

Lansdale had American money and power behind him, and had terrific political instincts, but what mattered most was the relationship. When admiring French officials wondered how Lansdale managed to “control” then-defense minister Magsaysay, he laughed. He explained it was less a matter of control than of listening and trust. He genuinely respected the Filipino leader. They developed shared goals. They were friends. Lansdale didn’t control the man, he influenced him.

Such subtlety eluded most of Lansdale’s peers and the press, which fell so in love with the idea of Lansdale as a mysterious puppet master that Oliver Stone would preposterously suggest in his film JFK that he was the ringleader behind the plot to kill Kennedy—a man Lansdale admired and who was then his only powerful ally. In Boot’s skillful telling, all of Lansdale’s surprising contradictions—a family man with a lifelong Filipino mistress, a general who disdained rank or formality and consistently counseled against using force, a notorious international backstage operator with an enduring faith in democracy and the cause of freedom—unspool over decades in a way that makes perfect sense.

After his Philippines triumph, Lansdale had less success in Vietnam with Diem, largely, in Boot’s telling, because rivals in the CIA, State Department and Pentagon undercut him continually.

It was hard to convince a new superpower in the mid-20th century to choose persuasion over firepower. The latter would prove tragically self-defeating in Vietnam, and is a lesson still unlearned more than three decades after Lansdale was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Mark Bowden is a best-selling author and journalist, best known as the author of Black Hawk Down. He has written 13 books, the most recent being Hue 1968. He is also a national correspondent for The Atlantic and a contributing editor for Vanity Fair.

* * *

Building a Supply Line on Short Notice

Logistics in the Falklands War. Kenneth L. Privratsky. Pen & Sword Books. 304 pages. $34.95

By Col. Steve Patarcity

U.S. Army Reserve retired

The success of any maneuver force, especially in expeditionary operations, hinges on effective logistical planning and execution from initial operations, to combat and thence to recovery and stability/post-hostility operations. Military forces that fail to consider or adequately address logistical considerations in their planning are doomed to mission failure.

In Logistics in the Falklands War, retired Maj. Gen. Kenneth L. Privratsky has written a fascinating and in-depth, meticulous and phenomenally well-researched account of the 1982 Falklands (or Malvinas, depending upon your sympathies) War, focusing on Great Britain’s mobilization, logistical planning and execution of the conflict. From the rapid decision to commence with operations to retake the islands, the U.K. faced almost insurmountable and complex problems over a more than 8,000-mile supply line. Issues ranged from obtaining adequate sealift, equipment, ammunition, fuel and supply transport and storage, logistics over-the-shore without an adequate harbor or support facilities in theater, bad weather—the list was seemingly endless.

Yet the prevailing mindset of the government, the military and the people was epitomized by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s confidently indignant and proud response. When asked about the chance of failure, she replied, “Failure? The possibilities do not exist!” That confidence and commitment to victory—walking hand in hand with superior planning and execution—enabled success in 74 days.

Privratsky opens his book with a good lead-in by covering the events leading to the Argentinian invasion and attempted annexation of the Falklands, as well as a brief political overview. He transitions rapidly into the accelerated efforts by Great Britain to marshal its forces and equipment for the coming conflict. From this point, he covers the operation in a complete and neatly organized manner from start to finish. His organization of text is superb—clearly correlating the distinct logistical challenges for each operational phase of the war plan. This enables the reader to clearly see and understand the logistical concerns facing commanders and logistical forces as well as their solutions as problems arose.

Privratsky has integrated the logistical aspects of the war into the discussion of the tactical aspects of the conflict—no easy task. His level of research is apparent, accomplished through maintenance of superb contacts with British forces as well as his use of complete and well-organized references and footnotes.

Privratsky’s book fills a niche not normally addressed in military writing and, to my knowledge, is the first to focus on the logistical aspects of Operation Corporate. In addition, while accounts abound on the strategic, operational and tactical aspects of warfare in all eras and conflicts, few have addressed the field of logistics. Logistics in the Falklands War provides these lessons not only for the career logistician, but also for the military leader and the amateur or professional historian.

Although the focus is logistics, the paramount lesson I took from this work is the necessity for leaders to not only conduct exhaustive planning and preparation but also to be inventive, flexible, clever and able to respond rapidly to changes on the battlefield due to unexpected circumstances. Privratsky’s work abounds with examples of this—from the expansion of Ascension Island as a logistical support base to the loss of the CH-47 Chinook helicopter fleet (on which resupply hinged so critically) to the lack of shore-based logistical support. One can see clearly how leaders responded and reacted.

As operations have been increasing in remote areas, over long supply lines and on short notice, this book offers many lessons. This is an excellent account on many levels with many teaching points—as an account of expeditionary warfare, as a worthy treatise on logistical planning and support at the strategic, operational and tactical levels, as an example of the importance of leadership in war and perhaps most importantly, as a showcasing of the ability of the soldier to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds to accomplish the mission.

Col. Steve Patarcity, USAR Ret., is a civilian strategic planner on the staff of the Office of the Chief of Army Reserve at the Pentagon. He retired in 2010 after 33 years of service in the active Army and Army Reserve, which included military police and armor assignments in the U.S., Kuwait and Iraq.

* * *

From War to Peace—A Reserve Officer’s Journey

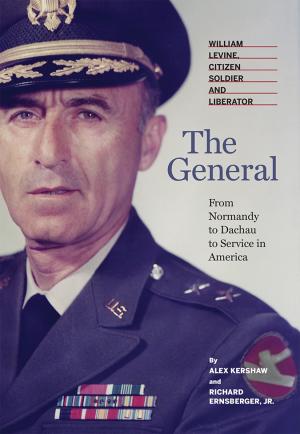

The General: William Levine, Citizen Soldier and Liberator. Alex Kershaw and Richard Ernsberger Jr. Pritzker Military Museum and Library. 128 pages. $19.95

By Dennis Showalter

The citizen-soldier is an American archetype. Citizen-generals have been overlooked. In this useful corrective, historian and author Alex Kershaw and journalist Richard Ernsberger Jr. unite to present a life and a career that stands as their archetype.

William Levine served his country in uniform through war and peace from his drafting in 1942 to his retirement in 1975 as a major general in the U.S. Army Reserve: one of those who shaped and nurtured America’s vital second line of defense in a vital quarter-century.

Levine was remarkably unremarkable. He left college before graduation to take a job as a salesman—a solid decision in the immediate post-Depression years. He awaited the draft out of concern for his new wife. He went through officer training—an almost automatic process for someone with his education. He landed in Normandy as an intelligence officer in an anti-aircraft battalion. These outfits were shuffled among divisions as needed, and Allied air supremacy meant their primary mission had a low priority.

Levine had time and opportunity to learn bits and pieces about the Nazi death camps, and on April 29, 1945, Lt. Levine entered the Dachau concentration camp as part of the 45th Infantry Division. Dachau was a life-defining experience for a man whose Jewish identity had been ethnic rather than religious/cultural. But Levine’s Yiddish proved a means of communicating with prisoners, and his service as an interviewer gave him a deep understanding of Nazi Germany’s crimes.

Levine returned to the U.S. in 1946. His postwar life was stereotypical for an ambitious upper-middle-class veteran. He relocated to Chicago and became a sales executive in a plastics firm—shades of The Graduate. He and his wife had two children and lived the upper-middle-class suburban life. And he never mentioned Dachau. But Levine did join the Army Reserve because, he said, he believed the U.S. would go to war with Russia. A son-in-law also noted that service was “an important part of his identity.”

Kershaw and Ernsberger make a useful contribution to our understanding of the evolution of the Reserve’s organization and missions, tracing Levine’s career through courses, classes and appointments, culminating in command of the 85th Infantry Division.

The 85th specialized in testing other Reserve units for their deployment readiness—no room for mediocrity. Levine was by all accounts a demanding leader who expected excellence but was fair and empathetic. His performance evaluations were complimentary. He understood the sacrifices that Reserve service demanded of soldiers and their families. How he would have performed in war remains an open question—command in combat is most often the province of relative youth. But there are worse sets of qualifications for division commanders than those developed by Levine.

He retired from the Reserve in 1975. He lost his wife to cancer, eventually remarried, and developed into an avid bridge player. He became increasingly involved with community affairs, both as a speaker and in management. And he began publicly incorporating his World War II experience—specifically, the meaning of Dachau and its lessons on the real meaning of war and hatred. He died in 2013.

At a time when masculinity is being re-evaluated, reconfigured and yes, reviled, it is appropriate to borrow from Shakespeare and say to all the world of Levine, “this was a man”—an American man.

Dennis Showalter is professor emeritus of history at Colorado College. He is past president of the Society for Military History, founding joint editor of War in History and a widely published scholar of military affairs. His recent books include Instrument of War: The German Army 1914-1918; The Wars of German Unification, 2nd edition; Armor and Blood: The Battle of Kursk; Hitler’s Panzers: The Lightning Attacks That Revolutionized Warfare; and Patton and Rommel: Men of War in the Twentieth Century.