August 2022 Book Reviews

August 2022 Book Reviews

Special Operations’ Rocky Evolution

Warfighter: The Story of an American Fighting Man. Col. Jesse Johnson With Alex Holstein. Lyons Press. 264 pages. $27.95

By Col. Keith Nightingale, U.S. Army retired

Retired Col. Jesse Johnson’s book Warfighter: The Story of an American Fighting Man, written with Alex Holstein, is a stirring, highly readable and satisfying work. It is a combination of special operations inside baseball as well as a descriptive trip through the life of one of America’s great soldiers.

The book describes the true nature of close combat, from Johnson’s time in Vietnam, through the earliest days of Delta Force, to the culminating success of special operations in the deserts of Kuwait and Iraq.

While this is one man’s journey and his tale, it is really about America’s rocky special operations evolution. That alone makes it a worthwhile and valuable read.

“The price of war was always paid in the currency of blood.” This sentence at the end of the book best summarizes its contents. Johnson’s adult life was spent fighting conflicts at the cutting edge. In the beginning, he was a grunt, killing and nearly being killed. Later, his career evolved into the more varied and nuanced conflicts of politics and bureaucracy. This was especially true for the evolving special operations programs where he was a primary player.

Johnson portrays, in a linear fashion, his time in uniform as a constant string of tough combat and serious adventures, working with a variety of senior figures along the way. Readers will recognize many of the names and events, and be enlightened as to the motivations and characters he unerringly describes. While unflattering in many cases, his descriptions are jarringly honest. There are warts, and Johnson correctly identifies them.

Vietnam was a searing experience, as he outlines, that established the core values he carried throughout his career. His unquestioned courage—as evidenced by a Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Stars and Purple Hearts—pales in significance to the experience itself. Johnson describes the events and the people who shared his crucible and forever shaped his judgment of men under fire—a judgment that was to serve him well throughout his career.

Johnson’s great gift for unraveling bureaucracies and attendant personalities is perhaps the book’s greatest strength. The true nature of people and organizations that view outsiders with fear and loathing is deftly revealed. His narrative about interactions with organizations and personalities trying to “help” while actively hindering is razor-sharp.

Johnson does a great service to the lay reader by explaining the complexity and interrelationships necessary to pull off special operations in today’s world. Nothing is easy in terms of ownership and execution, and divergent personalities. Johnson lays this out in detail in his discussion of the failed 1980 Iran hostage rescue attempt, the 1981 terrorist kidnapping and subsequent rescue of Brig. Gen. James Dozier in Italy, and his engagement as Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf’s special operations chief during operations Desert Shield and Storm.

Today, we look on all the forces and capabilities Johnson helped create and assume it was always smooth sailing. Johnson shows just how hard it was to make things happen due to the attitudes of the time and the personalities who viewed his life and organizations with abject suspicion, if not outright hatred.

This is a superb book tracing the life of a modern-day warrior—in other words, the quintessential American story of an ordinary person doing extraordinary things. This book is well worth the read and highly educational for those not immersed in “the business” of special operations.

Col. Keith Nightingale, U.S. Army retired, served two tours in Vietnam, participated in the 1980 Iran hostage rescue attempt and managed the U.S. Southern Command’s program to capture Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar. After retiring from the Army, he joined Science Applications International Corp., known as SAIC, and managed several security teams in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is the author, most recently, of Phoenix Rising: From the Ashes of Desert One to the Rebirth of U.S. Special Operations.

* * *

Chronicling the End of the Enemy’s Days

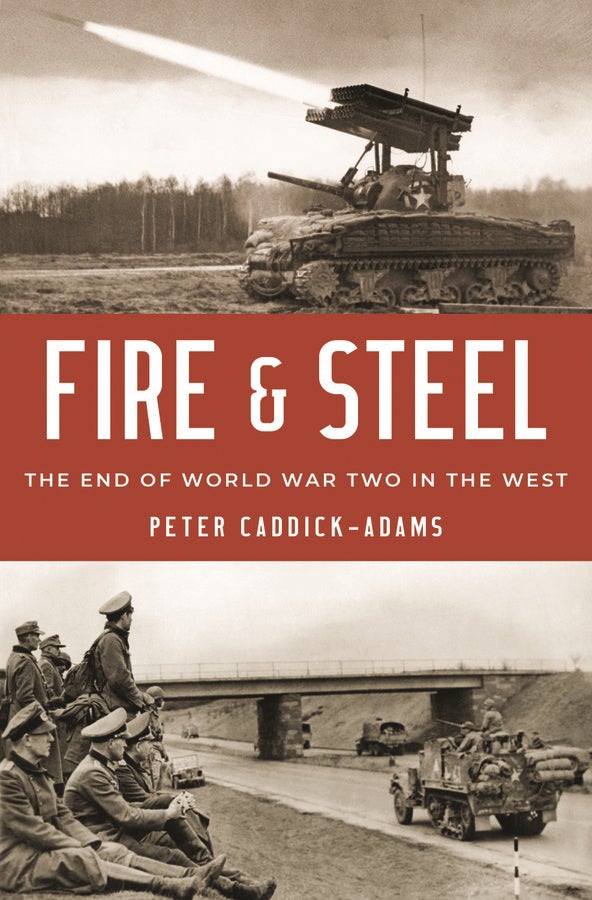

Fire and Steel: The End of World War Two in the West. Peter Caddick-Adams. Oxford University Press. 620 pages. $34.95

By Col. Gregory Fontenot, U.S. Army retired

British soldier-historian Peter Caddick-Adams has finished the last panel in his triptych on World War II in the West. Fire and Steel: The End of World War Two in the West is a strong finish that merits high praise as good history and great storytelling.

The author’s skills as a historian and insights as a soldier shine through without the pedantry of the guns and guidons approach to history. While mindful of the broader political context, this is first and foremost the story of soldiers and civilians who lived and fought through the last 100 days of the war.

Caddick-Adams does not shrink from the grotesque discoveries made at concentration and forced labor camps, nor from the comic opera fanaticism of diehard Nazis. Finally, he takes the reader through the dangerous endgame to wipe out the last German strongholds located between the Western Allies and the Soviets.

The scale of the effort is not well understood. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, Caddick-Adams writes, “assembled seven Allied Armies, totaling 4 million men and women.” Central Europe is cut by rivers bounded by forests and rippled with mountains ranging from the Harz mountains in the north to the Alps in the south. Operational maneuver on the scale seen on the Eastern Front was simply not possible.

Overshadowed by the seizure of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, Germany, the British 21st Army Group assault across the Rhine deserves more attention than it has enjoyed in American accounts of the war. Caddick-Adams points out that the operation was second “only in ambition and scale to D-Day.” He notes that British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was indeed “risk-averse” in his approach to the battle. Mindful of the bloodbaths of World War I, Montgomery always sought to avoid casualties.

Caddick-Adams’ account of the fighting to take Nuremberg, Germany, “the shrine of National Socialism,” is riveting. The towns taken along the way, including Bamberg and Erlangen, are reminders of Cold War service in Germany. Karl Holz, a Nazi Party functionary, put up furious resistance at Nuremberg. Rather than surrender, Holz killed himself, but not until claiming in a last communique that “the National Socialist idea shall win and conquer all diabolical schemes.”

Sympathy for the Germans eroded upon discovery of concentration camps such as Belsen in the north and Dachau in the south. The dead stacked like cordwood and emaciated survivors traumatized their liberators, including Staff Sgt. J.D. Salinger, later famous for his book The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger observed, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live.”

As the Western Allies and the Soviets approached each other, both took steps to avoid fratricide. Stop lines and coordination prevented what could have been an even uglier end to the war. The concern about a final redoubt in the German Alps led to operations to seize Berchtesgaden and other Nazi sites. Hitler, for all his histrionics, proved weak in the end. His confidants concluded, “The Führer has collapsed; he considers further resistance useless.” He then retired ignominiously to his bunker.

There is more, much more, and all of it carefully documented. The last two chapters, “Eight Days of Agony and Ecstasy” and “Aftermath,” are particularly good. Caddick-Adams shows the Allies’ determination not to visit a Carthaginian peace on Germany. The destruction of German infrastructure and its capacity to grow food or make anything had largely been destroyed. In the end, those who slew the monster realized they would need to help rebuild the land.

Fire and Steel is a worthy last panel in Caddick-Adams’ work.

Col. Gregory Fontenot, U.S. Army retired, commanded a tank battalion in Operation Desert Storm and an armor brigade in Bosnia. A former director of the School of Advanced Military Studies, his most recent book is Loss and Redemption at St. Vith: The Seventh Armored Division in the Battle of the Bulge.

* * *

Son Writes of His Father’s Trial by Fire

At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse. Walt Larimore and Mike Yorkey. Knox Press. 480 pages. $35

By Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Personal stories of “the greatest generation” remind us of the indomitable will of soldiers who stand at the vanguard of freedom. In At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse, authors Walt Larimore and Mike Yorkey recount the heroics of Larimore’s father, a junior officer who served in the 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division. The book traces the combat odyssey of Lt. Philip Larimore Jr., who fought on World War II’s “forgotten” southern European front.

Walt Larimore and Yorkey are prolific writers. Larimore has 40 books to his credit; Yorkey has authored and co-authored over 110 books in many genres. At First Light is the result of more than 15 years of painstaking research by Larimore to honor “[his] father’s legacy as well as the men he fought with and the women who aided in his recovery,” according to Larimore’s epilogue.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1925, Larimore’s father became an accomplished horseman and later earned the distinction of being the youngest second lieutenant in the Army at 18 years old after he graduated from Officer Candidate School. Transferred overseas, Philip Larimore received his baptism by fire in February 1944 on the Anzio beachhead in Italy, where he served as a platoon leader.

After receiving his first Silver Star on the Italian mainland, he participated in Operation Dragoon—the invasion of southern France—and subsequent advances into the Vosges Mountains and the Colmar Pocket, both in France, and finally, Germany.

On April 3, 1945, Larimore led a secret one-day mission into Czechoslovakia to rescue the famous Lipizzaner horses, prized by European royalty. Five days after, Larimore suffered a severe leg wound and later received his third Purple Heart and second Silver Star. Surgeons subsequently amputated Larimore’s leg above the knee.

Larimore’s postwar legacy is more remarkable than his combat exploits. According to the authors, Larimore was one of the 15,000 American soldiers wounded in action who required a major amputation. Rather than bemoaning his fate, Larimore successfully lobbied the War Department to remain on limited duty. During his therapy, Larimore joined the Atlanta Hunt Club, where he could put his equestrian skills to better use.

A year later, Larimore was reassigned as executive officer of the 2511th Special Ceremonial Detachment at Fort Myer, Virginia. His chief duties encompassed performing ceremonial tasks such as standard and full-honor funerals at Arlington National Cemetery, wreath ceremonies at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and military reviews in support of senior Army leaders and retiring soldiers.

In 1947, Larimore appeared before the Army Retiring Board and was found permanently incapacitated for active service. Though disappointed that he could not remain on active duty, Larimore was delighted to hear that his second Silver Star had been upgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross. He was officially discharged from the Army in July 1947. Taking advantage of the GI Bill, he earned a master’s degree from the University of Virginia.

Larimore died on Oct. 31, 2003, and was buried with full military honors at Port Hudson National Cemetery, Louisiana.

At First Light is a riveting story that rivals Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. We are in Walt Larimore and Yorkey’s debt for making Philip Larimore’s story accessible to the American public.

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He holds a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.

* * *

The Rise and Success of a Codebreaker

Parker Hitt: The Father of American Military Cryptology. Betsy Rohaly Smoot. University Press of Kentucky. (An AUSA Title). 320 pages. $29.95

By Elizabeth Cobbs

An author who makes you laugh with her first line is onto something special. Or someone special.

Betsy Rohaly Smoot’s new biography, Parker Hitt: The Father of American Military Cryptography, could be subtitled How to Live a Life. Written carefully, yet with panache, Smoot’s book echoes the temperament of the adventurous innovator it concerns. Readers interested in an iconoclast who was also a good Army man will not be disappointed in this lively, detailed chronicle of someone who, when all was said and done, knew how to choose his priorities.

Born in 1878, Hitt evokes a time when the Army—and America—had to reinvent itself quickly and on the fly. The 20th century opened with a panoply of new technologies and challenges. The child of a Methodist family that was “never quite wealthy, but never entirely impoverished,” Hitt grew up in a home where he imbibed the idea that pursuing one’s dreams and marrying the right person summed up the keys to success. That, and owning a dog.

Nearly all the gadgets that figured prominently in 20th century warfare arrived during his youth: electricity, cars, airplanes, telephones, radios and automatic weapons. Hitt found them fascinating.

In 1898, the 19-year-old with straight A’s dropped out of the cadet corps at Purdue University in Indiana to liberate Cuba from foul imperialism. Or so he understood that crusade. Hitt never looked back, serving afterward in combat in the Philippines, as senior signal officer for the American Expeditionary Forces in France and at a desk during World War II building communications systems.

Along the way, he wrote the Army’s first manual for decoding secret messages and recruited its first female soldiers. Author of The Manual for the Solution of Military Ciphers in 1916 and creator of one of the first coding devices, he was considered the father of cryptanalysis.

The Army was still small and peripatetic. When Hitt’s unit in the Philippines ran short on supplies, the lanky sportsman hunted ducks and deer to round out its rations. When he noticed that the steam coming off the water-cooled Vickers-Maxim machine gun could reveal a unit’s location to the enemy, he repurposed a rubber tube from a bathroom to divert the vapor. He stumbled across the intelligence that helped Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston capture Filipino revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo, attended the Army’s first flight school and worked closely with the great men of his era, from John Pershing to George Marshall to Dwight Eisenhower.

A talented, mostly self-taught engineer, Hitt built bridges, made maps, constructed roads, redesigned weapons and constructed telephone systems across hundreds of miles. He loved the infantry. Among his many talents, he excelled at the rifle.

Col. Hitt did just about everything in the Army except rise to general officer rank. Smoot builds a careful case to explain why. The things that some people admired about Hitt were ones that some did not: He spoke his mind. While good-humored and gregarious, he did not trim his opinions around the egos of others. He placed mission first. Hitt was willing to admit when he was wrong, but equally assured when he was right. He enjoyed the company of his wife—a codebreaker, too—and had a feminist perspective on the potential contributions of women to warfare. Plus, he simply did not prioritize advancement.

Had he played his cards right, Hitt’s name would be more well-known. The choices he made make for a more interesting book and a more admirable man.

Elizabeth Cobbs holds the Melbern G. Glasscock Chair in American History at Texas A&M University and is the author of The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers.