On the 50th anniversary of the all-volunteer force, the important question is: “How has the move to manning the Army without relying on conscription fared?” The short answer: Quite well.

Over the past half-century, the Army has transformed from an organization of largely first-term draftees and draft-motivated volunteers into a career-oriented force of experienced, motivated soldiers, proven in peace and war.

While some still regret that most American citizens will not serve their country in the military, few in service or out would vote to reinstate the draft. The reasons are the same today as they were 50 years ago when conscription was ended.

First, volunteer service is a grand Anglo-American tradition. Only when the most immediate threats to the country’s survival have demanded it, as in the Civil War, World War I and World War II, has America successfully opted to compel its citizens to serve. Aside from such times, the draft has been problematic at best or outright divisive, as during the Vietnam War.

Second, even then, conscription only gained the support of the American people when it was seen as universal and fair, impacting all equally either for military service or selectively to advance the war effort—thus the term “selective service.” Such a situation did not exist during the post-World War II period or during Vietnam, and it does not exist today, when the need for people to staff today’s technologically sophisticated Army is so small compared to the size of the potential population that might be called to service.

This does not mean that running the Army without the ease of simply requisitioning needed recruits to fill the ranks is effortless. Relying on volunteers is demanding, uncertain and costly. The story of how the Army has done this over the past half-century is worth telling, if for no other reason than to guide leaders in maintaining and reaping the benefits of the all-volunteer force moving forward.

Unpopular War

Problems maintaining the post-World War II draft came to a head in the late 1960s with an unpopular war in Vietnam and the way the draft was implemented. Sen. Sam Nunn, D-Ga., then-chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee’s manpower and personnel subcommittee, captured the mood of the country when he told Congress, “The all-volunteer force is to a large extent a political child of the draft card burning, campus riots and violent protest demonstrations of the late 1960s and early 1970s.” Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon also argued that the draft was “a system of compulsory service that arbitrarily selects some and not others [and] simply cannot be squared with our whole concept of liberty, justice and equality under the law. … The only way to stop the inequities is to stop using the system.”

Within days of taking office in 1969, President Nixon acted and set up an outside commission under the leadership of former Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates Jr. to assess the feasibility of a volunteer force and suggest ways ahead. Nixon also initiated changes to the existing draft to reform the system if the Gates Commission decided moving to an all-volunteer force was not practicable. The commission unanimously found that the cost of an all-volunteer force was “a necessary price of defending our peace and security” and recommended that military pay be raised, the conditions of military service and recruiting be improved and a standby draft system be established.

On Sept. 28, 1971, Nixon signed the enabling legislation to end conscription and put the reformed Selective Service System on “standby.” However, it would not be until Jan. 27, 1973, that Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced that “use of the draft has ended.”

The initial transition to an all-volunteer force for the Army was encouraging—so much so that the Army raised enlistment standards and terminated the Project Volunteer programs designed to improve recruiting. The impact of these actions was an immediate drop in enlistments, with some charging that the Army was “sabotaging” the new all-volunteer force.

New Tools

The situation started to improve in September 1973 with a change in leadership and more direct efforts to improve market research and analysis. Until then, personnel research had been focused on draft-related questions of “selection and classification.” Now, a new paradigm had to be learned that considered market response to changing levels of compensation—pay, bonuses and quality-of-life benefits. New skills and tools had to be developed to facilitate recruiting. An important initiative was the development of a new qualification test—the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB)—that would create significant problems in the years ahead.

If the number of recruits and their quality—based on test scores and high school graduation rates—were the standards by which the all-volunteer force would be judged, some argued that the financial cost was also critical. In November 1973, Congress established the Defense Manpower Commission to “focus on the substantial increase in the costs of military manpower.” The commission reported in April 1976 that “there is no immediate action available to substantially reduce manpower costs.” If the commission could not find ways to reduce costs, President Gerald Ford’s administration would, such as restraining military pay increases, enacting military retirement reform, reducing special pay and entitlements, and imposing military grade controls. The most problematic cost-cutting, however, came in the sensitive area of recruiting.

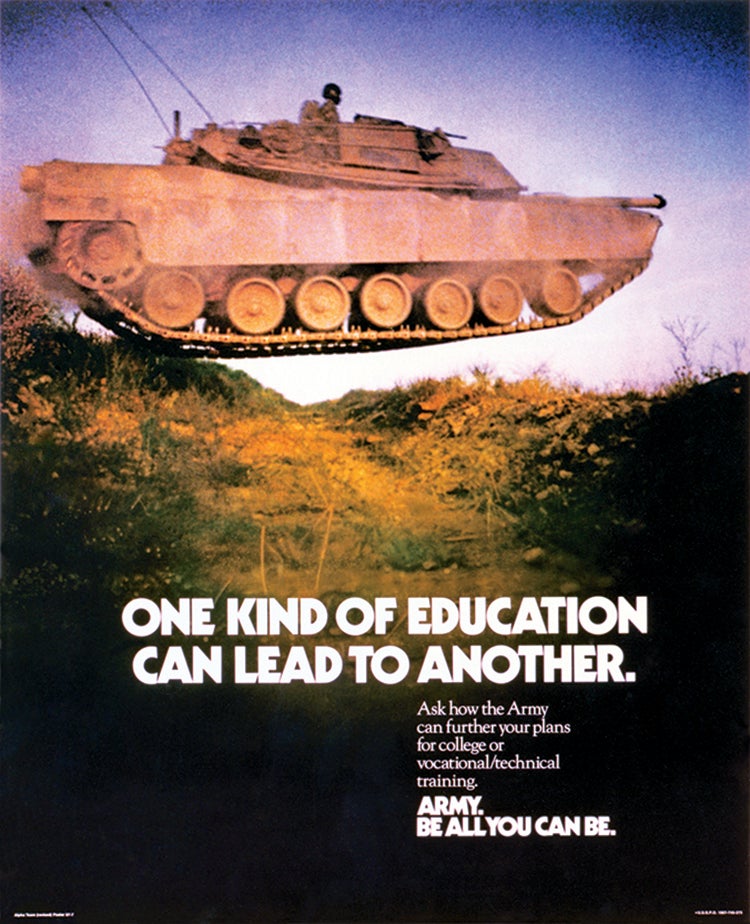

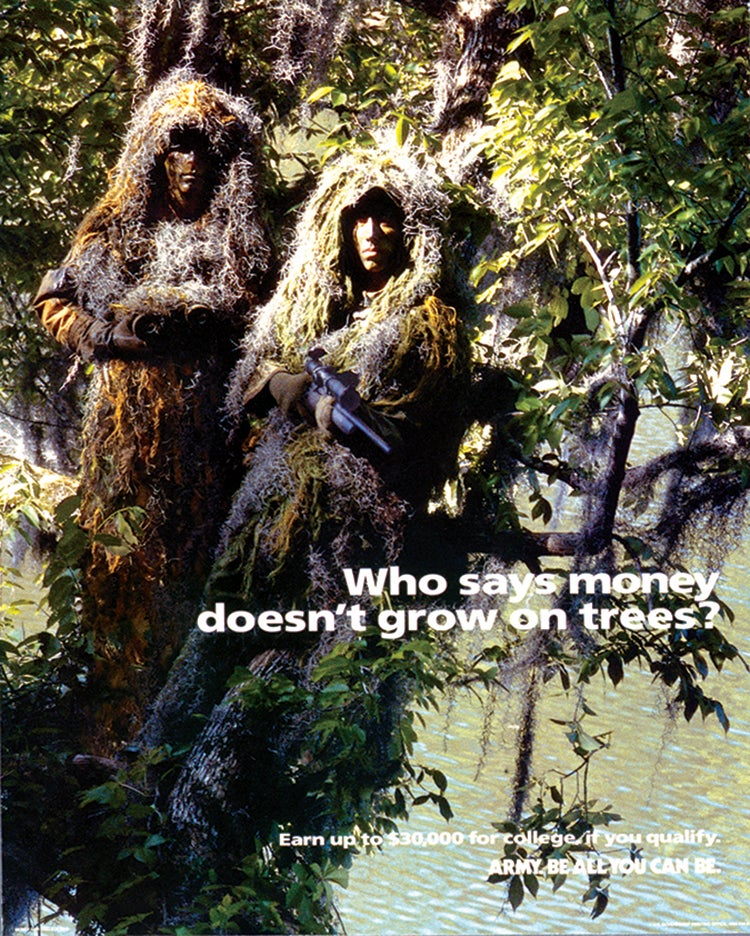

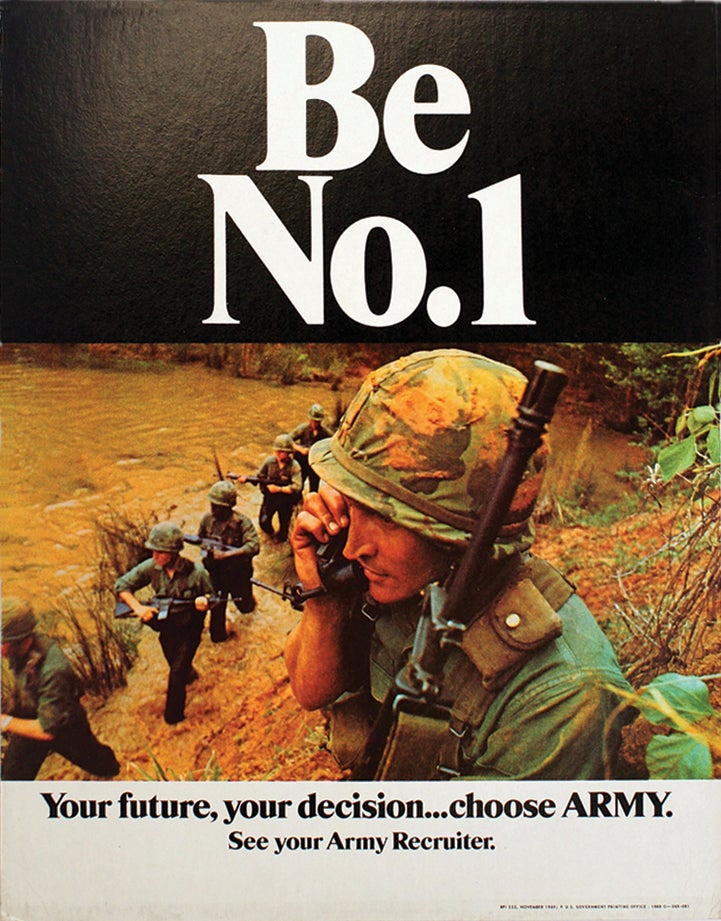

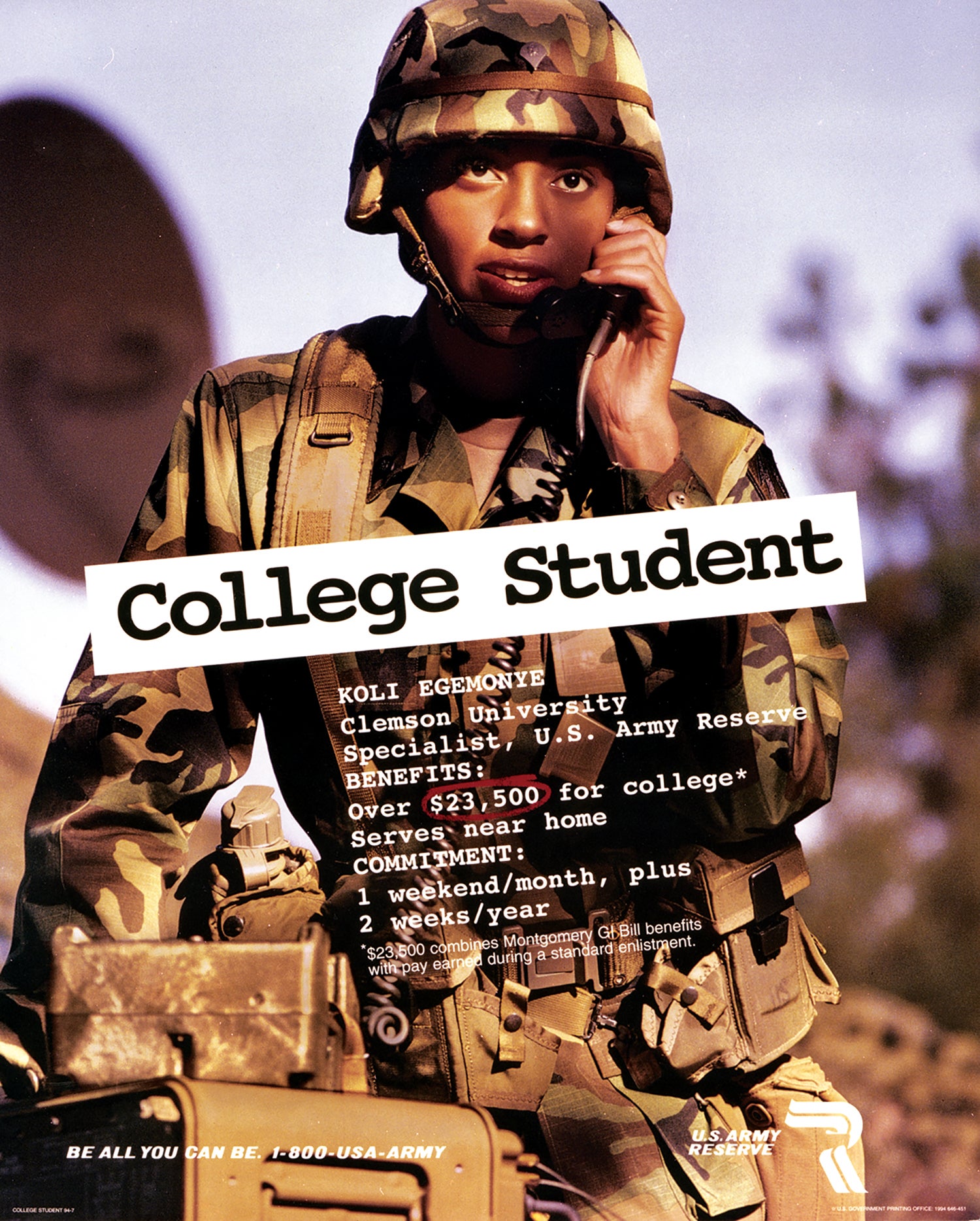

The administration of President Jimmy Carter, who took office in January 1977, soon found itself engaged in a series of contentious congressional hearings over the future of the all-volunteer force. To address the recruiting and quality issues, the administration started experimenting with recruiting options, aggressively moving to test the effects of advertising, fielding a new bonus program and moving to open the services to women. By midterm, an internal Pentagon assessment was not encouraging. Recruiting was down, with the services missing their numbers.

However, one bright spot reported that the overall quality of recruits had improved, at least as measured by ASVAB scores. As it turned out, even that was wrong: The apparent reduction in the lowest category of recruits was the result of miscalibration of the 1976 ASVAB. Recruit quality, in fact, had fallen, and the trend was down. However, this was the nadir of the all-volunteer force. Soon, two things changed—one in the Pentagon and one in Congress—that would put the all-volunteer force on a new path.

Financial Lifeline

At the Pentagon, Maj. Gen. Maxwell Thurman was appointed head of the U.S. Army Recruiting Command. Known for his analytic approach to problem-solving, he soon “taught the Pentagon how to recruit,” as defense analyst and retired Col. M. Thomas Davis put it in a Jan. 16, 2000, Washington Post online article headlined “Operation Dire Straits.” In Congress, two of the most ardent opponents of the all-volunteer force, Sens. Nunn and John Warner, R-Va., provided a lifeline to rescue the all-volunteer force in the form of an 11.7% across-the-board pay increase and an increase in the defense budget top line to pay for it. Soon, recruiting and retention were up, with the services meeting their goals.

The administration of Ronald Reagan that took office in January 1981 doubled down on the 1979 pay raise with an additional 14.3%, for a combined 26% pay increase in two years. This, together with an increase in the youth unemployment rate, made the military more attractive. So much so that a new, unexpected problem arose: the uncontrolled growth of the career force, and an increase in associated personnel costs as retention dramatically increased.

The fundamental personnel structure of the military was changing because of the move to the all-volunteer force. In the pre-Vietnam draft era, few enlisted personnel—only 3% to 4%—served long enough to retire. By the late 1980s, it was estimated that 18% of the force would be retained until retirement, and the number was rising. This new career-oriented force structure was put to the test during the presidency of George H.W. Bush as the new all-volunteer force was called to combat in Kuwait in 1991.

Early all-volunteer force critics had argued that responding to financial incentives suggested recruits were mere mercenaries and would not fight when the time came. Operation Desert Storm proved the opposite. Arguably, the all-volunteer force was the finest military force the U.S. ever sent into battle.

The volunteer force was tested again in 2001 and 2003 with combat in Afghanistan and Iraq, and with it came a call by some to “bring back the draft.” It was claimed that the poor and minorities were overrepresented in the military and were being used as cannon fodder. In fact, Black people were underrepresented in the infantry. Ultimately, the U.S. House voted 402–2 to reject a return to the draft.

Factors for Success

The question remains: Why has the all-volunteer force been a success? There are likely four main reasons:

1. Top management attention—leadership—starting with the president and secretary of defense.

2. A new breed of skilled practitioners exemplified by Thurman.

3. Consistently adequate budgets.

4. The benefit of critical research and analysis largely provided by the federally funded research and development centers operated by the Rand Corp., the Center for Naval Analyses and the Institute for Defense Analyses. This point is well illustrated by the federally funded centers’ work with the 9th Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation between 1999 and 2002 on restructuring military compensation.

By the late 1990s, the all-volunteer force system had fundamentally changed who serves in the military. Research showed the traditional image of an enlisted force made up primarily of high school graduates and paid accordingly was no longer accurate, with a quarter of senior enlisted having either a technical or college degree. These 1999 findings were reinforced as retention in the mid- and senior enlisted grades had recently declined.

To address these new realities, the 9th Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation recommended, and Congress approved for the first time since 1971, a restructuring of the military pay table with substantial increases in pay for the senior enlisted grades. The changes had little impact on total personnel costs, because there are only a small number of senior positions, but profoundly impacted retention as junior personnel looked to the future to see a financially improved career path. As a result of these changes, mid- and senior-grade retention was not a problem during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

So far, the all-volunteer force has proven to be resilient. Those charged with managing the force are vigilant and, with knowledge gained from 50 years, will certainly do their utmost to ensure its continued success.

However, only time will tell, as all depends upon the support of the American people and Congress continuing to vote the funds and provide the programs necessary to recruit quality soldiers and retain them and their families. This backing so far has made the all-volunteer force a success.

* * *

Bernard Rostker is an adjunct senior fellow at the Rand Corp., Washington, D.C. He served as director of the Selective Service System; assistant secretary of the Navy for manpower and reserve affairs; undersecretary of the Army; and undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness. He is the author of I Want You!: The Evolution of the All-Volunteer Force and America Goes to War: Managing the Force During Times of Stress and Uncertainty.