Understanding Service Across Generations

Military Culture Shift: The Impact of War, Money, and Generational Perspective on Morale, Retention, and Leadership. Corie Weathers. Elva Resa Publishing. 352 pages. $34.95

By Terri Barnes

Military Culture Shift: The Impact of War, Money, and Generational Perspective on Morale, Retention, and Leadership challenges military leaders, current and potential, to dig into the causes and characteristics of changing military culture and how it affects problems facing today’s military. Author Corie Weathers asks readers to examine their own presumptions, listen to stories from other generational perspectives and seek effective ways to address complex problems.

The scope of the book is ambitious, starting with U.S. military history since World War I and creating context for the ways that military culture has shifted from 9/11 to the present. Weathers considers budgetary issues, promotions, military spouse culture and other factors, and examines how advances in technology and generational perspectives create issues that today’s military leaders must address.

In this widely researched, hefty volume, Weathers creates a narrative that is balanced, deeply informative and readable. She draws on hundreds of sources—including media reports, personal interviews and scholarly research—without using jargon. She leverages her experience as a mental health clinician, leadership consultant and military spouse, but doesn’t base her conclusions solely on her own viewpoint. She examines her own bias and invites readers to do the same.

“It is easy to assume that if we share the same values, even a similar lifestyle within the military, then everyone’s experience must also be the same,” she writes, but adds that “each generation experiences military culture in a different way. Depending on when you enter the community … you are likely to experience historical events, social norms, and even the concept of community differently from others around you.”

Recognizing differences between generations serving in the military, from baby boomers to Generation Z, is a key theme of the book. Weathers points out the reasons that each generation responds to different styles of leadership, communication and influence. She also identifies events and conditions that have catalyzed changes in military culture for generations. Among these are the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the mental health crisis, political polarization, a global pandemic, the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, scandals over poor conditions in military housing and more.

All these converging pressures, Weathers explains, make the military system prone to “wicked problems” that leaders must address. Wicked problems, she explains, are problems exacerbated by changing or confusing information, stakeholders with conflicting values and new problems that may emerge in response to solutions for the original problem. For example, she describes “the near-impossible task of recruiting the next generation while simultaneously healing the current one.”

“We cannot pretend that the only issues in recruiting Gen Z is that they are less patriotic or less prepared mentally or physically [or that] families are less willing to participate in the military lifestyle because spouses are working full-time jobs,” Weathers writes. “The youngest generation has seen and heard about the issues of toxic leadership, sexual harassment, watched the Afghanistan exit live-streamed, and are daily weighing their options of what kind of organization they want to be a part of. ‘There’s a hole in the bucket, Dear Liza.’ ”

However, Weathers has not written an answer book for today’s problems. Military Culture Shift is a guide to help leaders, current and future, to develop skills and tools for problem-solving across generations.

This book doesn’t only belong on every military leader’s desk for use in professional settings. It belongs on the bedside table of anyone who seeks to better understand military culture and have a meaningful and positive influence on it.

Terri Barnes is a military spouse, book editor and author of Spouse Calls: Messages from a Military Life, based on her column in Stars and Stripes.

* * *

How to Build a New Unit From Scratch

Green Light, Go!: The Story of an Army Start Up. Col. David Rowland. Köehlerbooks. 372 pages. $28.95

By Lt. Col. Nathan Finney

Some readers of ARMY magazine will have written a history of their time in a unit, whether formally or just by capturing thoughts and notes in a green notebook as part of daily life in uniform. From time to time, some leaders, especially those in unusual situations, get the opportunity for such reflections to be published. Green Light, Go!: The Story of an Army Start Up is the tale of one of those situations.

The book is the personal story of then-Lt. Col. David Rowland, commander of a new battalion in a new security force assistance brigade (SFAB). Throughout his book, Rowland details the challenges and successes of creating this special military unit from scratch, a relatively infrequent opportunity for a commander.

The main thrust of Rowland’s argument is that the creation of his unit was akin to an entrepreneur building a startup, requiring the characteristics and spirit typically found in technologists or businesspeople in Silicon Valley—including curiosity, adaptability, self-motivation, tenacity and comfort with failure.

Undoubtedly, creating a unit from scratch for a new mission requires different leadership skills than a more typical command, but Rowland’s overemphasis on equating this to startup culture sometimes distracts from the otherwise compelling narrative found in Green Light, Go! That said, this approach could appeal to those in uniform who at times treasure leadership lessons from popular business literature (even though those lessons are often gleaned from military leaders in the first place).

Green Light, Go! is organized into three parts. The first part addresses the mission to stand up the 1st Battalion of the 5th SFAB, which would focus on peacetime activities in the Indo-Pacific and recruiting the right personnel for that mission. The second part details the training and preparation for deployment into the theater and the challenges of creating buy-in for the mission. The third part of the book covers the execution of the battalion’s mission in select countries in the Indo-Pacific and the effects of its actions.

Additionally, Rowland’s introduction is a great summation of why and how the Army established the SFABs. This section is written clearly and at a level that will be of significant value to historians and those who are generally interested in the subject, yet who are unfamiliar with the intricacies of the Army institution.

The greatest insight from Green Light, Go! is how the unit appeared to be a solution in search of a problem. Rowland details the work required just to get buy-in from those the SFAB was designed to support—including geographic combatant commands, U.S. country teams and partner-nation militaries.

Despite pushback in the theater (which sometimes led the author to come across as knowing better than the foreign national and U.S. military leadership at levels above the SFAB), Rowland’s team appears to have been successful in countries that were the easiest to enter or eager for support, versus those of most strategic importance to defense or national interests.

However, looking at the mission and importance of the 5th SFAB today in the Indo-Pacific, the work done by Rowland and his team undoubtedly set the foundation for increasing relevance over time.

Green Light, Go! is a quick read and would be useful for captains preparing to go into command, majors bound for operations officer or executive officer jobs, and lieutenant colonels preparing for battalion command. Rowland’s insights help frame possible command challenges and approaches to overcome them, allowing the reader to think through their own solutions before meeting such obstacles.

Lt. Col. Nathan Finney is a special assistant to the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Camp Smith, Hawaii. Previously, he was a U.S. Army Goodpaster Scholar at Duke University, North Carolina. He is a founder of The Strategy Bridge, the Military Writers Guild and the Defense Entrepreneurs Forum. He holds a doctorate in history from Duke.

* * *

Unit Kept Germans Guessing

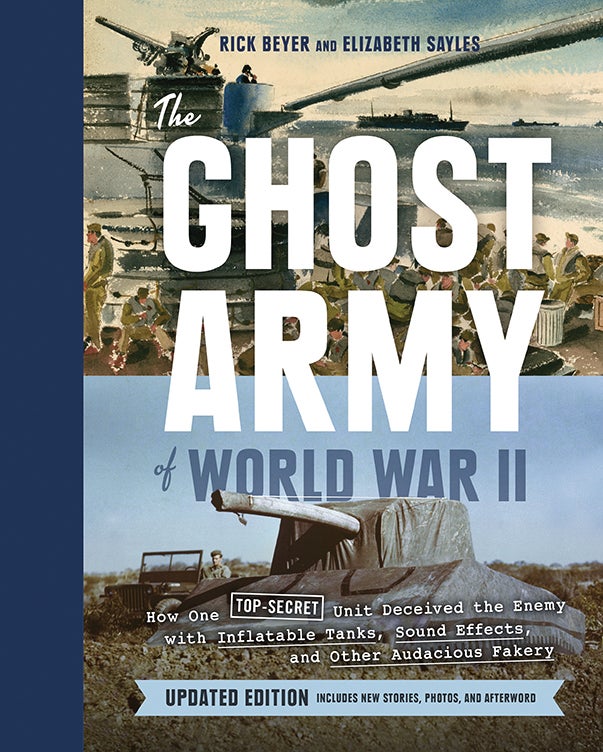

The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery. Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles. Princeton Architectural Press. 272 pages. $45

By Matthew Seelinger

In this updated version of The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery, first published in 2015, authors Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles tell the story of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, better known as the “Ghost Army,” and its service with the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II. This new volume features additional images, biographies of veterans compiled by the Ghost Army Legacy Project and information on the Ghost Army receiving the Congressional Gold Medal in 2022.

Activated on Jan. 20, 1944, and arriving in Europe in May of that same year, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops was designed to confuse and deceive the enemy. It was composed of a headquarters company and four line companies, each with special skills: the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion (scenery, inflatable props, insignia, costumes); 244th Signal Company (radio deception); 3132nd Signal Service Company (sound effects); and 406th Engineer Combat Company (security, construction, demolition).

Not to be confused with the British-led Operation Fortitude, designed to lead the Germans to believe an Allied army group led by Maj. Gen. George Patton Jr. would land at Pas-de-Calais and not in Normandy, both in France, the 23rd accompanied American forces as they advanced east, using a variety of techniques and equipment to mislead the Wehrmacht as to the disposition and strength of U.S. Army units.

Beyer and Sayles do an excellent job of thoroughly detailing the Ghost Army’s service, including its training in Tennessee and New York, its deployment to England and additional training there, its arrival in France in late June 1944, its advance into Germany through V-E Day and its redeployment back to the U.S. for expected service in the Pacific Theater.

The men of the Ghost Army used a variety of methods to deceive the Germans, including the use of inflatable tanks, vehicles and artillery pieces; fake radio traffic; and sound effects from large speakers mounted on half-tracks.

Beyer and Sayles also describe what was referred to as “special effects”—sending men from the 23rd, wearing uniforms and driving vehicles with fake unit insignia and markings, into villages with known enemy collaborators and spies in the hopes that misinformation would make its way back to the Germans.

Many of the men in the Ghost Army, especially those serving with the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion, were skilled artists, and several would go on to become renowned in the art world, including fashion designer Bill Blass. Many of these men kept sketchbooks and painted watercolors during the war, and several examples appear in the book.

While The Ghost Army of World War II will appeal to readers interested in World War II, anyone who appreciates art, especially by soldier-artists, will find much to like in this fully illustrated book.

Beyer and Sayles conclude with an afterword that describes how many families of Ghost Army veterans contacted them after the publication of their book in 2015 to share stories, photographs, artwork and other material, which led to this updated volume. They also describe the campaign to get the Ghost Army federal recognition and award of the Congressional Gold Medal.

The Ghost Army of World War II is a book that will appeal to a wide audience, from World War II readers and those interested in soldier art, to today’s soldiers serving in psychological operations.

Matthew Seelinger is the chief historian at the Army Historical Foundation and editor of the foundation’s quarterly journal, On Point.

* * *

Gettysburg Hero Proved Leadership Skills

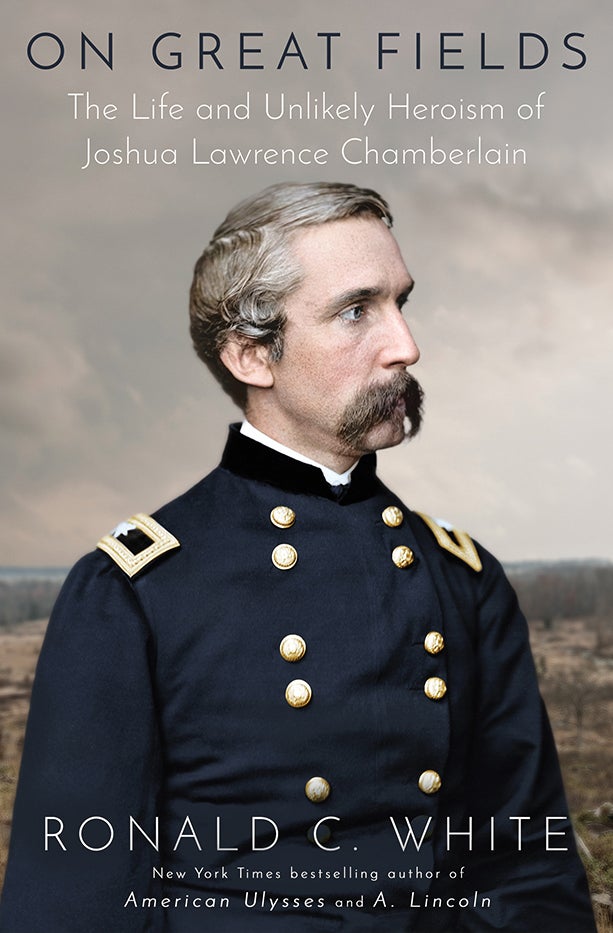

On Great Fields: The Life and Unlikely Heroism of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Ronald White. Random House. 512 pages. $35

By Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Ever since Michael Shaara’s now-classic 1974 novel of the Civil War, The Killer Angels, and Ken Burns’ 1990 PBS miniseries The Civil War, Union Maj. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain has earned the admiration of the military community for his leadership at Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg.

In the latest biography of this legendary warrior, On Great Fields: The Life and Unlikely Heroism of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, author Ronald White has produced the most comprehensive assessment of Chamberlain since Alice Rains Trulock’s 1992 biography, In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain and the American Civil War.

White writes, he says in his prologue, “neither to lionize nor prosecute Chamberlain, but to try to understand and appreciate the life and times of this courageous and controversial man.”

White is a bestselling author and one of the United States’ premier biographers, with American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant and A. Lincoln: A Biography to his credit. White divides Chamberlain’s life into five time periods, ranging from the foundation of his character in antebellum Maine to what White terms the retired general’s “interpreter” phase, during which he offered lectures about the Civil War and the challenges facing his state and the nation in a rapidly changing culture.

What separates On Great Fields from previous works is White’s detailed analysis of his subject’s antebellum career and his life following the Civil War. However, readers of ARMY magazine will be far more interested in Chamberlain’s military service and his views on character-based leadership during times of crisis.

Responding to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers on July 1, 1862, Chamberlain wrote Maine Gov. Israel Washburn Jr. to offer his services. Declining a full colonelcy, Chamberlain accepted Washburn’s appointment as second-in-command of the 20th Maine Volunteer Regiment.

Chamberlain’s regiment saw limited action in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam, Maryland, but received its baptism by fire at Fredericksburg, Virginia. After accepting a promotion to colonel, Chamberlain led the regiment in its heroic defense of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, for which he received the Medal of Honor. In describing the largest battle of the war, White presents a provocative parallel with Chamberlain and his principal adversary, William Oates of the 15th Alabama Regiment.

White does not confine his analysis of Chamberlain’s leadership to the action at Gettysburg. He dedicates several chapters to the battles of Petersburg and Five Forks, both in Virginia.

At Petersburg on June 18, 1864, Chamberlain received a near-fatal wound that would sideline him until the final months of the war. Now a brigade commander, Chamberlain played a pivotal role in the Union victory of Five Forks on April 1, 1865. The Confederate defeat at Five Forks paved the way to Gen. Robert Lee’s ultimate surrender to Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9.

Three days following Lee’s capitulation, Grant designated Chamberlain to command the surrender ceremonies. As the Confederate soldiers surrendered their arms, Chamberlain ordered his command to shoulder arms in salute, offering “recognition, not to the Confederacy or the cause, but rather to the bravery and courage of the soldiers in ragged uniforms marching toward him,” White writes.

White concludes Chamberlain’s military career with the Grand Review of the Armies on May 23 and May 24, 1865, to honor the victorious troops. That review served as “a line of demarcation for Chamberlain [from] his vigorous army life … to a peaceful, familiar college town in Maine, but facing an unknown future,” White writes. Four terms as Maine governor and a presidency at Bowdoin College, followed by a distinguished career as a public lecturer, conclude White’s narrative.

If there is a lesson for leaders in today’s Army, it is the importance of continuous learning. Chamberlain said it best: “I have always been interested in military matters, and what I do not know in that line I know how to learn.”

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He holds a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.