Ukraine and Proxy War: Improving Ontological Shortcomings in Military Thinking

Ukraine and Proxy War: Improving Ontological Shortcomings in Military Thinking

by LTC Amos C. Fox, USA

Land Warfare Paper 148, August 2022

In Brief

- Though often overlooked or misinterpreted, proxy war is an important component of armed conflict. Policymakers and practitioners must understand the nuance of proxy war to avoid making missteps in policy and practice.

- A proxy war can take the form of the more-recognized traditional model or of the technology diffusion model. In the traditional model, a principal actor uses a proxy for the day-to-day rigors of combat against an enemy. But in the technology diffusion model, a principal actor provides its agent with financing, weapons, training and equipment.

- Recognizing proxy war’s subcategories, and not misidentifying them as either a coalition or an alliance, is crucial to crafting policy, strategy, plans and doctrine.

Introduction

Proxy war is an underappreciated component of warfare. In many cases, proxy war is omitted from discussions of international armed conflict, relegated to non-international armed conflict and the realm of non-state actors. This taxonomy is incorrect because it overlooks the ways in which state actors use other state actors, in addition to non-state actors, to engage in proxy war.

Further, Western militaries and pundits alike tend to place proxy war in a category outside the bounds of acceptable practice. Instead, they often label proxy war a nefarious activity conducted by cynical strategic actors.1 To be sure, a quick scan of U.S. Army doctrine, for instance, yields scant mention of proxy war, and when proxy war is mentioned, it is applied to non-state actors and to how an adversary operates.2 This is also an incorrect categorization of proxy war.

These two ontological misconceptions are the primary factors derailing a clear understanding of how proxy war fits both within warfare and within war as a whole. The ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War provides the defense and security studies communities a ripe opportunity to review their understanding of proxy war and to rectify ontological incongruencies.

The Russo-Ukrainian War demonstrates that proxy wars are not solely the action of cynical, revanchist actors operating through non-state actors. Rather, it is a striking example of how state actors fight proxy wars through other state actors. To that end, multiple Western nations are engaged in a proxy war against Russia to support and defend democratic ideals, the rule of law and the international system.3 However, to see beyond proxy war’s ontological misgivings, and square the circle, a solid theoretical foundation is required. This paper, building on existing proxy war literature, seeks to provide that foundation by introducing two forms of proxy war: the traditional model and the technology diffusion model. This paper builds on those two forms of proxy war and asserts that each form contains two subcategories: state actor and non-state actor. In short, this paper adds to the existing literature on proxy war by injecting four new named and categorized subjects into the field’s taxonomy to overcome the ontological shortcomings of proxy war.

Proxy Wars—A Taxonomy

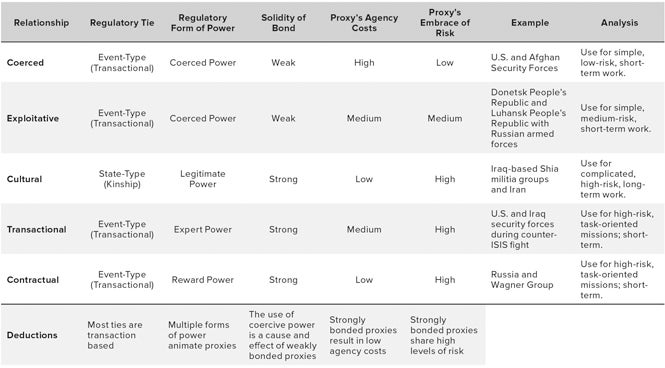

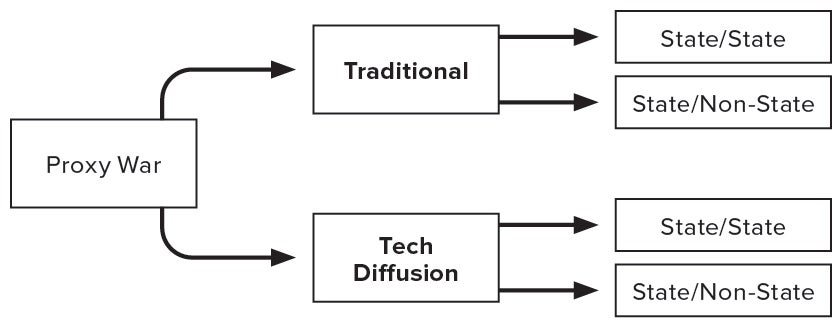

A proxy war is armed conflict, whether international armed conflict or non-international armed conflict, in which one side (or more) uses an intermediary as its primary combat force to achieve its strategic aims.4 Within proxy wars, five basic strategic relationships exist: coercive, exploitative, transactional, cultural or contractual.5 Those relationships guide the interaction between principal and proxy (see Figure 1). Further, the unique structure of each strategic relationship governs what a principal can expect from, and accomplish with, its proxy. These five relationships come to life in proxy war’s two basic forms—the traditional model and the technology diffusion model (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Five Models of Proxy War (Enlarge)

Figure 1: Five Models of Proxy War (Enlarge)

Figure 2: Two Forms of Proxy War

Traditional Model

Proxy war’s traditional model results from a principal actor using a proxy for the day-to-day rigors of combat against an enemy. This is the most common form of proxy war and what most people envision when “proxy war” is mentioned. The use of combat advisors, especially at the tactical level, is one of the primary indicators of this form of proxy war. Iran’s use of Iraq-based Shia militia groups to combat the U.S. military during both Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Inherent Resolve are recent examples of this form of proxy war, something to which the U.S. military can easily relate.6

Two subcategories exist within the traditional model. The first subcategory occurs when a state actor uses a non-state actor as its proxy. This category aligns with the Iranian model described in the previous paragraph and is the most recognizable form of proxy war.

The second subcategory is less common than the previous, but still pervasive. The second subcategory results from a state actor enlisting another state actor as its proxy, whether explicitly or implicitly, to fight against a common foe. Although it is easy to confuse this subcategory as a coalition or an alliance, it differs in that the principal does not fight alongside the proxy; instead, it provides the proxy with combat support. Combat support often comes in the form of planning, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), targeting, strike and logistics. This category is also characterized by the use of combat advisors, although many of those combat advisors are far closer to the front or fulfill a dual role, both advising and carrying out combat support.

As David Lake notes in a contemporary work on proxy war, the United States’ support to the post-Saddam government of Iraq typifies this subcategory.7 In post-Saddam Iraq, the United States developed, financed, equipped and trained the Iraqi security forces.8 The United States then used the Iraqi security forces to combat Iranian interference in Iraq and to lead the U.S. effort to snuff out the growing post-Saddam insurgency.9 The Iraqi security forces fought alongside and, later, in front of U.S. forces during this war.10 That is not to say that the U.S. military did not conduct unilateral operations, because it did. However, as the war progressed, the U.S. military relied more on the Iraqis for combat operations and took a back seat, offering advice, training and logistical support.11

Operation Inherent Resolve, on the other hand, also provides an example of the traditional model’s state actor/state actor subcategory. Despite being outfitted with friendly terms and phrases such as “partner” and “advise and assist,” the United States’ operational and tactical level reliance on the Iraqi security forces to combat the Islamic State meets the definitional requirements of a proxy war.12 U.S. forces provided combat advisors and planning and logistics advisors, and they covered discrete capability gaps for the Iraqis, to include ISR, targeting and precision strike. All of these factors combine to meet the standard for a traditional principal-proxy relationship.13

To reiterate, the traditional model is the most common form of proxy war. Within this model, two subcategories exist—one in which a state actor fights through a non-state actor, and the other in which a state actor fights through a state actor. It is important to remember that the state actor/non-state actor subcategory can be mistaken as a coalition or an alliance, but proxy relationships are discernible by the degree to which participants share tactical and existential risk.14 In situations in which the risk is offloaded to one actor, and the other actor (or actors) remain(s) relatively clear of harm’s way, the situation is likely a proxy war and not a coalition or an alliance.15

Technology Diffusion Model

The technology diffusion model is proxy war’s second form. This model results from the principal providing its agent with financing, weapons, training and equipment instead of indirectly fighting through the proxy. This model is often a third-party actor’s pragmatic response to the actions of an aggressor state against a weaker actor. Further, this form of proxy war is useful for opportunistic principals interested in seeing an adversarial state actor fail in a third-party conflict. The technology diffusion model is often indicated by operational and strategic combat advising, but also by the use of technical advisors. Technical advisors often operate in third-party countries and train and educate the proxy on the use of foreign-supplied equipment and weapons. The technology diffusion model also has two subcategories.

The first subcategory is the result of a principal providing a non-state actor with financing, weapons, training and other equipment to combat an enemy, but not taking an active role in the fighting itself. This subcategory is fairly common. The United States’ support for the mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989) is perhaps one of the best-known examples of this model.16 The U.S. Stinger missile came to be seen as a meme of U.S. involvement in that war, as the Stinger missile decidedly assisted the mujahideen defeat of the Soviet Union. Moreover, Russia’s support to the Taliban and its affiliates during the U.S. war in Afghanistan (2001–2021) is another example of this proxy arrangement.17

On the other hand, the second subcategory results from the principal providing another state actor with financing, weapons, training and other equipment to combat an enemy, but not taking an active role in fighting. From a historical standpoint, the United States’ support for Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988) is an example of this situation.18 However, the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War is a more tangible illustration of this subcategory.

From a technology diffusion standpoint, the United States has provided Ukraine with military aid exceeding $4.6 billion since February 2022.19 As recently as 31 May 2022, President Biden reiterated the United States’ commitment to Ukraine’s survival and, conversely, the thwarting of Moscow’s policy aims in Ukraine.20 The most recent aid package, valued at $700 million, includes High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), towed 155 millimeter artillery, a panoply of unmanned aerial systems and a wide variety of other weapons and related equipment.21 Furthermore, American combat advisors trained Ukrainian soldiers in Germany on the use and upkeep of the U.S.-provided combat equipment, to include its towed artillery.22

It is important to note that the donation of money, equipment and weapons does not necessarily equate to an actor engaging in proxy war. Stated or unstated, an actor’s involvement meets proxy war criteria mainly based on the intent behind its contributions and the degree of its support. It is also important to remember that press releases, open-source documents and doctrines often obfuscate intent and methods and instead focus on communicating a narrative. To that end, because a state actor is not using the phrase “proxy war” does not mean that they are not engaged in that activity. In both cases, resource commitment and intent—not words—are the surest way to discern if an actor has committed to a proxy war or if it is just providing a needy international actor with support.

Conclusion

Proxy wars must always be at the fore of warfare studies because they dominate both international and non-international armed conflict. Further, proxy war’s nuance is important to understand because misunderstandings can cue missteps, from the policy level all the way to the tactical level of war. Providing a clear taxonomy for proxy war, as this paper does, helps overcome ontological shortcomings that also contribute to poor showings in proxy war.

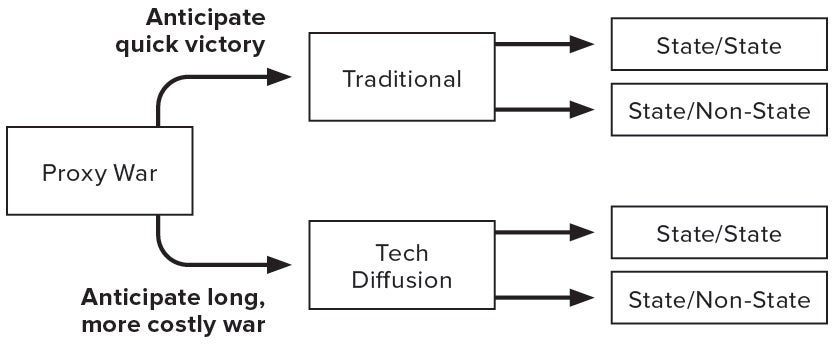

Looking to the future, as the international system continues to rely on a rules-based international order, the student of warfare should expect to see a few trends in future war. First, in cases in which maligned state actors attempt territorial conquest vis-à-vis another state, one should anticipate a pragmatic response from third-party actors. If the third party elects a proxy war strategy, one should expect it to employ the traditional model against adversaries that it expects to defeat relatively soon. However, if the third party assesses a longer, more costly war, but goes with a proxy strategy, one should anticipate the technology diffusion model (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Anticipated Applications

Second, the method of identifying a proxy is less a selection process than it is assessing the available actors and evaluating one’s capacity to create a proxy from the groups of fighters, partisans or like-minded people, then being able to transition it into a coherent force that can be put in the field to combat an adversary. In most cases, proxy selection is pragmatic and dynamic—it is based on how available resources allow for the quickest solution.

Finally, the student of warfare must expect proxy wars to continue at a regular clip in the cycle of violence that permeates the modern world. Proxy war provides policymakers, strategists and practitioners with quick, relatively cheap and low-risk (to oneself) options for the continuation of policy aims. The flexibility of proxy war strategies means that they will remain at the fore of international and non-international armed conflict for the foreseeable future.

★ ★ ★ ★

Lieutenant Colonel Amos C. Fox is an officer in the U.S. Army. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Reading (UK), Deputy Director for Development with the Irregular Warfare Initiative, and he is an associate editor with the Wavell Room. He is also a graduate from the U.S. Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was awarded the Tom Felts Leadership Award in 2017.

- DoD, Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy, 2020, 2–3.

- Amos Fox, “In Pursuit of a General Theory of Proxy Warfare,” Land Warfare Paper 123 (February 2019): 3–5.

- Fred Kaplan, “Everyone Is Starting to Admit Something Frightening about Ukraine,” Slate, 29 April 2022.

- Vladimir Rauta, “Proxy War and the Future of Conflict: Take Two,” RUSI Journal (2020): 4–5.

- Amos Fox, “Strategic Relationships, Risk, and Proxy War,” Journal of Strategic Security 14, no. 2 (2021): 6–19.

- Jeanne Godfroy et al., The U.S. Army in the Iraq War, Volume 2: Surge and Withdrawal, 2007–2011 (Carlisle Barracks, PA: United States Army War College Press, 2019), xxxiii–xxxvi; Phillip Smyth, “The Shia Mapping Project,” Washington Institute for Near East Peace Policy, 20 May 2019.

- Dave Lake, “Iraq, 2003–2011: Principal Failure,” in Proxy Wars: Suppressing Violence Through Local Agents, ed. Dave Lake and Eli Berman (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 238–48.

- Jeanne Godfroy et al., The U.S. Army in the Iraq War, Volume 1: Invasion, Insurgency, Civil War, 2003–2006 (Carlisle Barracks, PA: United States Army War College Press, 2019), 169–88.

- “Proxy Warfare in the Greater Middle East and Its Periphery,” New America.

- “Operation Together Forward I,” Institute for the Study of War; “Operation Together Forward II,” Institute for the Study of War.

- Godfroy et al., U.S. Army in the Iraq War, Volume 2, 459–70.

- Frank Hoffman and Andrew Orner, “Dueling Dyads: Conceptualizing Proxy Wars in Strategic Competition,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 30 August 2021.

- The White House, “Letter to the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Regarding the War Powers Report,” 8 June 2022.

- Fox, “Strategic Relationships, Risk, and Proxy War,” 17–18.

- Fox, “Strategic Relationships, Risk, and Proxy War,” 17–18.

- Christian Parenti, “America’s Jihad: A History of Origins,” Social Justice 28, no. 3 (2001): 31–38.

- Charlie Savage, Eric Schmitt and Michael Schwirtz, “Russia Secretly Offered Afghan Militants Bounties to Kill U.S. Troops, Intelligence Says,” New York Times, 26 June 2020.

- Lake, “Iraq, 2003–2011,” 238–40.

- Dan Lamonthe et al., “U.S. Defends Supplying Advanced Rocket Systems to Ukraine,” Washington Post, 1 June 2022.

- Joseph Biden, “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, 31 May 2022.

- Antony Blinken, “$700 Million Drawdown of New U.S. Military Assistance for Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State Press Release, 1 June 2022.

- Stephen Losey and Joe Gould, “From Howitzers to Suicide Drones: Pentagon Seeks Right ‘Balance’ on Training Ukrainians on New Arms,” Defense News, 9 May 2022; Jim Garamone, “US Troops Train Ukrainians in Germany,” DOD News, 29 April 2022; Andrew Kramer and Maria Varenikova, “Powerful American Artillery Enters the Fight in Ukraine,” New York Times, 23 May 2022.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.