The Russia-Ukraine War One Year In: Implications for the U.S. Army

The Russia-Ukraine War One Year In: Implications for the U.S. Army

by Charles McEnany & COL Dan Roper, USA, Ret.

Spotlight 23-1, March 2023

Issue

At its one-year mark, the Russia-Ukraine war provides insights regarding selected characteristics of warfare and the trajectory of U.S. Army and joint force transformation for large-scale combat operations.

Spotlight Scope

Provides land warfare implications impacting the U.S. Army, the joint force and Congress—as well as allies and partners—based on observations from the conflict.

Insights

- The ascendency of fires, enabled by pervasive surveillance, underscores the imperative of the Army’s long-range precision fires and layered air and missile defense modernization.

- Large, resilient stockpiles of prepositioned precision and conventional munitions are integral to U.S. strategic responsiveness.

- The Army’s Multi-Domain Task Forces appear well-suited to the battlefield characteristics on display in Ukraine.

- The Army requires 3–5 percent annual budgetary growth to transform land warfare capabilities on pace with other warfighting domains.

Introduction

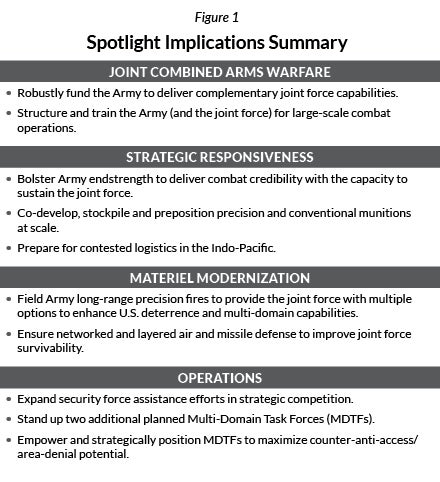

Russia’s year-old war in Ukraine has returned conventional conflict to Europe at a scale not seen since World War II. This Spotlight analyzes the war across four lenses relevant to transforming the U.S. Army for large-scale combat operations (LSCO)—joint combined arms warfare, strategic responsiveness, materiel modernization and operations—and provides implications pertinent to the Army, the joint force and Congress—as well as to allies and partners (Figure 1).

The implications aim to support the Army’s contribution to the 2022 National Defense Strategy’s (NDS’s) three core tenets: integrated deterrence, campaigning and building enduring advantages.1 Through integrated deterrence, DoD intends to deter adversaries by synchronizing its efforts across warfighting domains, regions and the spectrum of conflict in conjunction with all instruments of U.S. national power. In part, DoD achieves integrated deterrence through campaigning: sequencing logically linked military activities to shift the security environment in favor of the United States. To enable integrated deterrence and campaigning, DoD must build enduring advantages by accelerating its modernization for the future fight. The NDS’s three tenets are interlinked; consequently, many of this Spotlight’s implications also overlap.

This Spotlight does not aim to address all elements necessary to build an effective Army as part of the joint force; it does not discuss personnel investments required to field a force motivated to fight and win the nation’s wars—that force which is the cornerstone of the U.S. Army. It provides early considerations that may bolster the joint force’s ability to deter future conflict or, if necessary, to prevail in it.

Limitations on War Analysis

Recognizing the context-dependent nature of warfare, analysts should not interpret the Russia-Ukraine war as entirely predictive of what U.S. and coalition forces could experience in a conflict with a peer competitor. DoD is transforming for LSCO, but the conflict in Ukraine does not meet the U.S. Army’s definition of LSCO (see note).2

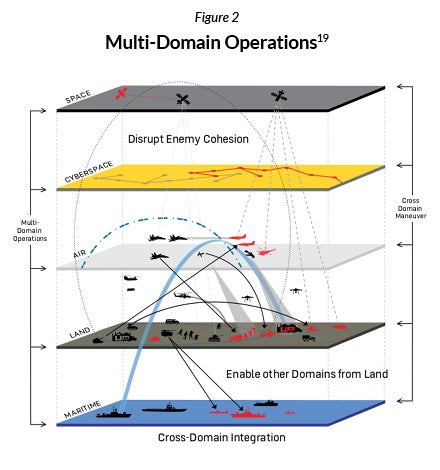

Moreover, Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) doctrine—“the combined arms employment of joint and Army capabilities to create and exploit relative advantages that achieve objectives, defeat enemy forces and consolidate gains on behalf of joint force commanders”3—is how the U.S. Army plans to fight in LSCO, but neither the Russian nor Ukrainian armies conduct MDO.

Given these limitations, this Spotlight avoids using the word lessons. Nevertheless, the war provides an opportunity to draw insights that may apply to future LSCO.

Joint Combined Arms Warfare

The United States requires an Army that is funded, structured and trained to provide decisive land power to the joint force.

Observation 1: The Russia-Ukraine conflict demonstrates that high-tech means of waging war have not replaced land warfare.

Until 24 February 2022, many observers doubted that Moscow would launch its attack, noting the damage it would do to Russia’s global standing. But states do not always act in ways that appear rational. While Western nations may not intend to wage wars of territorial aggression, they cannot mirror-image adversaries’ intentions. Failing to prepare for these wars only benefits aggressive revisionist states.

Although analysts in recent years have devoted much focus to modern, high-tech systems and hybrid, asymmetric and nonlinear warfare that deemphasize large-scale combat, Russia’s war in Ukraine has been primarily conventional. As General Christopher Cavoli, commander of U.S. European Command and Supreme Allied Commander Europe, put it, “The great irreducible feature of warfare is hard power. . . . If the other guy shows up with a tank, you better have a tank.”4

Ukrainian soldiers of the 1st Battalion, 28th Mechanized Infantry Brigade take cover behind their BMP-2 armored vehicle while other soldiers rush ahead to breach a wire obstacle blocking their unit's advance during training at the Yavoriv Combat Training Center, near Yavoriv, Ukraine, on 16 March 2017 (U.S. Army photo by Sergeant Anthony Jones).

Implication 1.1: Congress should ensure that the Army and the joint force each receive 3–5 percent real annual growth.

For the joint force to prevail against a peer competitor, it must converge the unique capabilities that each service provides across the five warfighting domains. A consistently false narrative in the defense community since 1945 has been that dominance in the air and sea will allow the United States to prevail in conflict “without the agony of ground combat.”5 This misperception negatively impacts joint force readiness. The Army has lost nearly $40 billion in buying power since 2019, despite accounting for about two-thirds of global U.S. Combatant Command requirements.6 As the land domain is often decisive, this leaves the joint force without the range of capabilities to deter adversaries or to prevail in sustained conflict.

The reasons for the continued relevance of ground warfare are numerous. Strategically postured land forces have unique deterrent effects.7 When deterrence fails, nations have historically struggled to achieve their aims with air or naval forces alone.8 Unsurprisingly, the Army has played the central role in all major U.S. wars since World War II, averaging about 60 percent of deployments to combat theaters and about 70 percent of wartime fatalities.9

The Army does much more than fight, however. Through its Title 10 executive agent responsibilities, it sets the theater and is the integrator of the joint force. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joe Dunford referred to the Army as the “linchpin” for combat operations: “I use that word—linchpin—deliberately, because the Army literally has been the force that has held together the joint force with critical command-and-control capabilities, critical logistics capabilities and other enablers,”10 such as base defense, transportation and engineering.

Implication 1.2: The U.S. Army must maintain adequate force posture (positioning, capacity and capability) in Europe after the Russia-Ukraine war.

Some have argued that the United States should reduce its posture in Europe11 and shift forces to the Indo-Pacific. But it is unlikely that the United States could do so within the next decade in a way that would strengthen deterrence for Taiwan (often the focus of those who make this argument) without accepting excessive risk in Europe.

It is premature to assume that the Russian government will abandon its desire for a regional sphere of influence. Moscow plans to grow its army from 1.15 million soldiers to 1.50 million by 2026,12 and it retains unconventional and asymmetric capabilities while it rebuilds its force. Likewise, it is unclear whether potential increases in European defense spending will translate into an integrated, combat-credible force. The United States and Europe have previously been surprised by the Russian military—notably in 2014 with their annexation of Crimea. The real possibility of needing to surge U.S. forces and infrastructure back to Europe, if indeed they did substantially shift to the Indo-Pacific, would be a lengthy and potentially vulnerable process in a crisis.

Observation 2: Russia and Ukraine have struggled to conduct combined arms maneuver at scale, rendering them more vulnerable to the reemergence of the defense as the stronger form of warfare.

The proliferation of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms coupled with fires has been a central element of the conflict. Some analysts contend that the war presages an era of defensive superiority in ground warfare, where defense, fires and attrition have an advantage over maneuver.13 Russia and (to a lesser extent) Ukraine have struggled to conduct combined arms—“incorporating a diverse array of combat arms into a single organization, so that the weakness of any single arm is compensated for by the other arms’ strength.”14 The lack of mutually supporting arms has made both forces increasingly vulnerable to the battlefield’s lethality.

Others argue that the superiority of the defense has rendered certain platforms obsolete. For example, citing Russia’s heavy tank losses—reportedly half of its T-72 fleet15—some contend that they have a limited role in a conventional conflict.16

The Russian army’s tank losses are due to its failure to conduct combined arms operations. In February and March 2022, Russian tanks sped toward Ukrainian cities, unsupported by dismounted infantry or air power, and were consequently vulnerable to agile Ukrainian defenders.17 There is no current substitute for tanks’ firepower and protection when employed correctly; but, like any other platform, if they are utilized without support, they will not be effective.

Implication 2.1: U.S. Army force structure and training must reflect the required scale of combined arms operations in LSCO.

As the battlefield has become more surveilled and lethal, efficient combined arms are vital to conducting offensive operations while limiting losses. Effective U.S. Army MDO that can create and exploit relative advantages against peer competitors in LSCO requires higher field headquarters to integrate complex campaigns across vast geographies (Figure 2). To achieve this, the Army is returning to its division-centric force structure, substantially improving the ability to conduct campaigns at the division, corps and theater levels.18

The Army and the joint force must train these formations at the required scale for LSCO. The Russian military incorrectly believed it could scale its force employment from smaller operations in Crimea and Syria to a large conventional war. The U.S. joint force should not similarly assume it can scale up from recent brigade-centric operations without extensive training.

The Army is expanding division-level training at the National Training Center; it conducted the first of these training exercises in 2021.20 As the joint force incorporates virtual reality, augmented reality and virtual gaming in training, DoD should facilitate this technology’s accessibility and interoperability with allies and partners.21 Doing so can ensure that these exercises continually expand in size and realism.

Strategic Responsiveness

Sufficiently sized, equipped and sustained forces are foundational to credible strategic responsiveness, i.e., “the ability to deploy the right mission capabilities to the right places at the right times to achieve decisive results” (see note).22

Observation 3: While not decisive, Russia’s force size advantage has allowed it to sustain the conflict.

The Russian military in February 2022 numbered 900,000 active personnel and 2 million in reserve,23 compared to Ukraine’s 196,000 active and 900,000 reservists. Based on poor operational planning, Moscow’s initial invasion force numbered only approximately 190,000.24 Current estimates are that Ukraine’s manpower figures grew to approximately 500,000 in the first few months of the war.25

As of February 2023, the British Defense Ministry estimated total Russian casualties (including private military contractors) at 200,000.26 U.S. officials have estimated at least 100,000 Ukrainian casualties.27

In early fall 2022, Russia began to address its manpower disadvantages. Moscow mobilized at least 300,000 new soldiers and sent approximately 150,000 to fill depleted units fighting in Ukraine.28 Despite these mobilized troops receiving poor training and equipment, Russia stabilized frontlines in eastern Ukraine in December 2022 and January 2023, making some territorial gains.

Implication 3.1: Congress should restore U.S. Army endstrength as recruiting recovers.

Force quality can offset some quantity shortfalls, but not unconditionally. It is concerning that the Army’s 452,000 active duty endstrength for Fiscal Year 2023 is at its lowest level since 1940. Future U.S. LSCO could take place in theaters much larger than Ukraine; the Army must be sufficiently sized to fight across vast geographies and to break through enemy defenses while possibly sustaining high casualty rates. Greater endstrength would ensure that the Army has the Soldiers to engage in combat and, equally as critically, the capacity to fulfill its role in sustaining the joint force in protracted campaigns. For its part, the Army must continue remedying recruiting shortfalls.29

Observation 4: The Russia-Ukraine war has been industrial in scale.

In November 2022, U.S. defense officials estimated that Russia fired 20,000 artillery rounds daily, while Ukraine fired 4,000 to 7,000.30 Despite significant pre-war stockpiles, Russia has expended precision-guided missiles so rapidly that U.S. officials believe it could be running low31 and that it has had to slow its rate of artillery fire by as much as 75 percent in some regions.32

Ukraine’s Western supporters have discovered their own readiness gaps. They are recognizing that they have forfeited long-term sustainability for cost efficiency, with defense industrial bases sized for peacetime minimum sustaining rates. The Center for Strategic and International Studies found that production lines for critical munitions in Ukraine, such as 155 mm projectiles, are either inactive or unable to meet the demands of a large-scale conflict.33 The U.S. defense industry can build about 14,000 155 mm howitzer rounds per month—an amount that Ukrainian forces have fired in just two days of heavy fighting.34

Munitions are prepared for shipment at Crane Army Ammunition Activity on 15 June 2020. Crane is one of 17 installations of the Joint Munitions Command and one of 23 organic industrial bases under the U.S. Army Materiel Command, which include arsenals, depots, activities and ammunition plants.

Implication 4.1: Congress should increase funding for multi-year contracts for the defense industrial base to create sufficient munitions stockpiles to enhance deterrence and be available before a conventional war begins.

“Just-in-time” delivery will not support U.S. munitions needs in a high-intensity conventional fight. The defense industrial base must produce sufficient stockpiles of these munitions unhindered by budgetary uncertainty. The Army has begun to make headway, planning to ramp up its production of 155 mm rounds from 14,000 to 90,000 per month,35 and it is awarding multi-year contracts for Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS).

There is still a long way to go. DoD should conduct analyses of estimated munitions expenditures for potential contingencies, recognizing that conflicts with peer adversaries are likely to be protracted. Moreover, in LSCO, peer adversaries may disrupt production. Congress should thus provide long-term funding to produce and stockpile these munitions before a conflict begins.

Implication 4.2: DoD should expand the co-development of essential equipment with its allies and partners while expediting foreign military sales (FMS) to Taiwan.

Co-production of critical equipment with allies and partners can build sufficient stockpiles and create supply networks with fewer single points of failure. Co-production is particularly vital for precision munitions that are more expensive and have longer production lead times. NATO or the European Union can facilitate this in Europe, while networks such as AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, United States) and the Quad (Australia, India, Japan, United States) should expand co-production tailored to the Indo-Pacific.

As another tool, FMS can lower DoD procurement costs for critical weapon systems while promoting interoperability with allies and partners. This requires strengthening the defense industrial base and reducing inefficiencies in the sales process.36 Given Taiwan’s priority to U.S. defense strategy, clearing its $19 billion FMS backlog should be a priority.

Implication 4.3: Congress should expand Army Prepositioned Stocks (APS) funding through the European Deterrence Initiative and the Pacific Deterrence Initiative.

The Army’s mobilization of 7,000 Soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Division to reassure NATO allies within days of Russia’s invasion was possible because of APS.37 These stocks are critical to the joint force’s strategic responsiveness through calibrated force posture—positioning the right mix of forces and capabilities. APS reassures allies and deters adversaries by ensuring that U.S. forces can rapidly transition to combat operations, if necessary. This posture supports the NDS’s tenets of deterrence and campaigning by enabling the joint force’s agility.

Observation 5: Russian logistics failures have hampered its operational and tactical readiness, but Moscow has been unable to impose similar disruptions to the flows of Western weaponry to Ukraine.

While the Russian military possessed relatively robust stockpiles of equipment (of varying quality), their operational logistics have been ineffective, especially in the early weeks of the war. Russian forces advanced beyond their supply, resulting in formations with little food or fuel that were vulnerable to Ukrainian fires.

Ukraine has benefitted tremendously from its border with NATO. Moscow has not struck the logistics stockpiles in adjacent NATO territories, which has allowed Kyiv’s supporters to flow equipment to Ukrainian soldiers. Russian forces have seemingly struggled to disrupt Ukrainian in-theater logistics effectively.

Implication 5.1: The Army, DoD and U.S. allies and partners must prepare for contested logistics in LSCO, particularly in the Indo-Pacific.

Producing equipment is only a portion of strategic responsiveness; U.S. forces can only be combat credible if they can get materiel to the theater, into the hands of Soldiers, and sustain it. But unlike Western security assistance efforts for Ukraine, in LSCO, contested logistics from “factory to fort to foxhole” is likely to be the norm. The United States and its partners cannot assume that they would be able to replicate the logistics support that they have demonstrated for Ukraine in a war with China over Taiwan. Even if U.S. and allied forces only sought to provide Taiwan with equipment, the People’s Liberation Army likely would try to blockade the island.

If U.S. and partner forces directly defend Taiwan, China would likely contest their logistics and force generation capabilities from points of origin in U.S. and allied homelands to forces in Taiwan. Beijing could employ cyber and space weapons to disrupt U.S. data and navigation. It could also use ISR and fires to place U.S. supply nodes and transport at risk. Soldiers, bases and infrastructure will need to be more distributed in the theater with lower signatures, placing a premium on precise, discreet supply. Military-industrial infrastructure must be resilient to cyber disruptions and kinetic effects outside the theater, including in U.S. and partner homelands.

Materiel Modernization

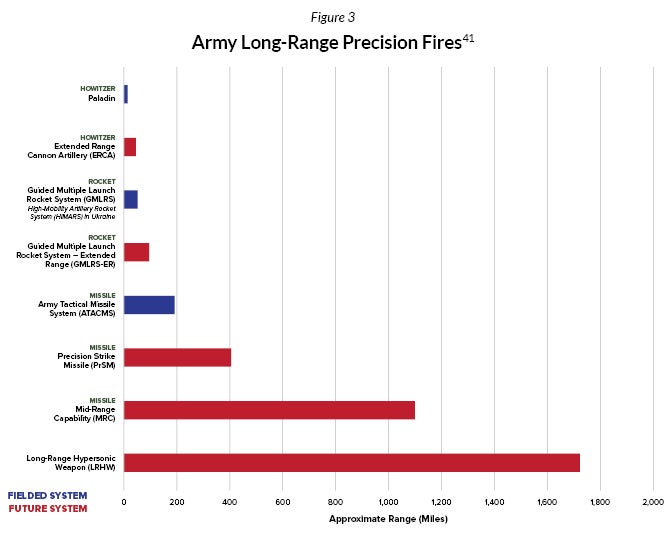

The Russia-Ukraine war indicates the re-ascendency of the fires warfighting function. This section discusses the two of the Army’s six materiel modernization priorities that are most relevant to this significant potential development—long-range precision fires (LRPF) and air and missile defense (AMD).

Observation 6: Ukrainian LRPF has significantly disrupted Russian operations and helped offset Kyiv’s mass disadvantages.

General James McConville, Chief of Staff, Army (CSA), called Ukraine’s employment of 20 U.S.-supplied High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS—which fire GMLRS munitions) a “game changer”38—helping Ukraine conduct its fall 2022 offensives.

With their 50-mile range, GMLRS fired from HIMARS allow Ukraine to strike precisely in-depth, placing previously secure Russian command and control (C2), logistics nodes and massed formations at risk by integrating targeting data from drones, satellites, geolocation and Western intelligence assistance. HIMARS’ precision has helped Ukraine offset its quantitative disadvantages in fires and reduce its logistical tail.39 The system has proved highly survivable with its mobility and small footprint.

The Russian military’s adaptations to move potential targets out of HIMARS’ range have spurred Kyiv to call for the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missiles, fired from the HIMARS platform, but with a range of 190 miles. At the time of publication, the United States has not sent any ATACMS missiles to Ukraine.

Implication 6.1: Congress should ensure timely funding for U.S. Army LRPF.

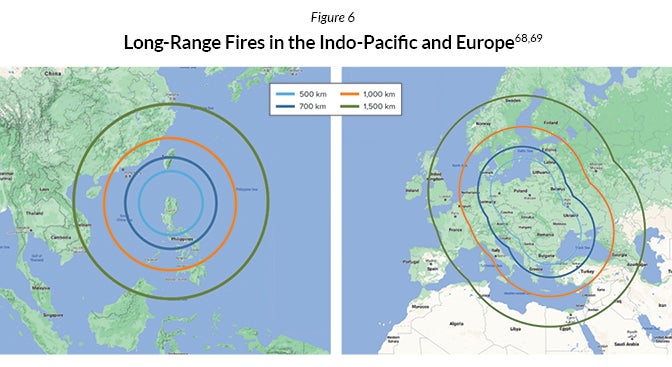

“Long-range” is relative when considering different platforms and theater geographies. HIMARS, Ukraine’s “long-range” capability, is not long compared to the Army’s anticipated LRPF suite (Figure 3). For example, the Army’s long-range hypersonic weapon, due to be fielded in Fiscal Year 2023, has a range of 1,725 miles. These survivable ground-based LRPF, alongside LRPF from the air and sea domains, provide complementary options to joint force commanders and pose multiple dilemmas for adversaries.40 LRPF is especially vital for the Indo-Pacific’s vast distances.

Implication 6.2: Even with greater precision, DoD should increase the quantity of massed conventional munitions.

While precision fires are more efficient than unguided munitions, Western nations cannot produce enough of them due to financial and production constraints. The Army can employ massed conventional fires against close-in massed formations of troops and weapons to offset shortfalls in precision munitions, reserving precision fires for long-range, high-payoff targets. DoD should not sacrifice massed fires on the assumption that precision munitions will be sufficient by themselves.

Observation 7: Diverse air and missile threats have imposed significant dilemmas on Russian and Ukrainian ground forces.

Russia and Ukraine have leveraged various air and missile systems—such as military and commercial satellites, unmanned aerial systems (UAS) and LRPF—for ISR and kinetic effects. Fixed-wing and rotatory aircraft have played a less significant role than many assumed they would, as both Ukrainian and Russian ground forces have denied air superiority to the other.

UAS have been particularly prominent. Russia and Ukraine have used military and commercial drones to spot adversary forces and to direct massed and laser-guided artillery fire.42 Both militaries have employed UAS with lethal capabilities, such as Ukraine’s use of the U.S.-made Switchblade loitering munitions and Russia’s waves of Iranian Shahed-136 drones.

Among air defense systems from Western allies, Ukraine has received two U.S. National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems, which have been effective in intercepting Russian cruise missiles43 and are incorporating a Patriot air defense battery.44 Washington has also supplied developmental counter-UAS (C-UAS) systems that utilize small rockets or electronic interference,45 but Ukrainian forces have often resorted to less technical means, such as 50-caliber machine guns.46

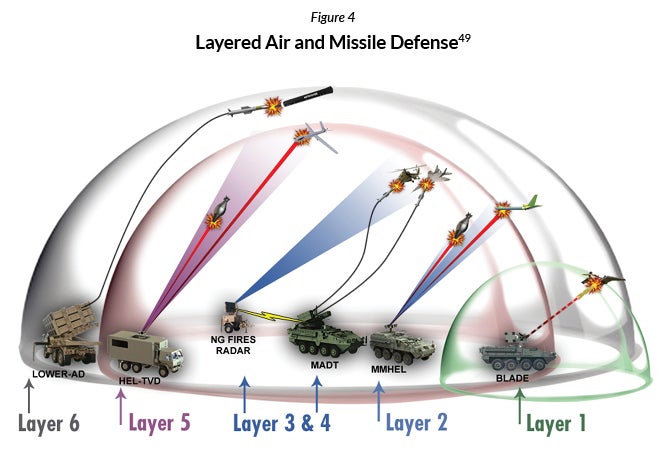

Implication 7.1: Congress should fully fund the joint force’s layered air and missile defense.

The most significant challenge to AMD is unlikely to come from a single capability but from attacks that “mix and match” multiple threats.47 In LSCO, adversaries could target military infrastructure outside the theater and even U.S. and allied homelands.

AMD must be sufficiently layered and interconnected, leveraging sensors across the joint force in an “integrated joint kill web” (Figure 4). This capability could protect forces from the homeland to the tactical edge against ballistic and cruise missiles; rockets, artillery and mortars; and UAS. To this end, the Army has completed initial operational testing for the Integrated Battle Command System,48 which integrates Army AMD sensors and shooters into a unified network as part of Joint All-Domain C2.

C-UAS is a critical gap. General McConville has compared the imperative to innovate C-UAS solutions to the Army’s “full court press”50 to mitigate risks from improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Iraq and Afghanistan.51 The Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office has conducted experiments with directed energy prototypes and microwave weapons that have shown early success against drone swarms.52 Sustained funding is necessary as potential U.S. adversaries increasingly employ UAS.

Operations

The Ukrainian military’s performance provides insight into how U.S. Army forces can effectively employ security force assistance formations and Multi-Domain Task Forces (MDTFs) to support the NDS.

Observation 8: Western security cooperation has been a huge force multiplier for Ukrainian forces.

Before February 2022, few observers believed Ukrainian forces could withstand a large-scale Russian attack. U.S. and Western security cooperation—equipment, training and intelligence—have been a significant reason for Ukraine’s ability to do so. As it is beyond this Spotlight’s scope to detail all Western efforts to arm and train Ukraine, it focuses on U.S. contributions. However, the implication also applies to U.S. allies and partners, many of whom have demonstrated a significant ability to build partner capacity.

The U.S.-Ukraine military relationship dates to 1993, when Ukraine partnered with the California National Guard through the State Partnership Program (SPP). Training efforts accelerated after the 2014 annexation of Crimea, primarily through U.S. special operations forces (SOF).

The United States has provided approximately $27 billion in military assistance since the war began—accounting for over 70 percent of all global military aid to Ukraine.53 Western training efforts in Europe and the United States have ramped up. The U.S. military has hosted Ukrainian forces at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to train on the Patriot missile system,54 and it has begun training Ukrainian soldiers on combined arms maneuver in Grafenwoehr, Germany.55

Western assistance has also included intelligence and operational planning: U.S. and NATO intelligence has enabled Ukrainian strikes on Russian targets,56 and Western military advisors were even reportedly involved in planning Ukraine’s Kherson counteroffensive.57

U.S. Soldiers demonstrate trench assault and clearance at the Yavoriv Combat Training Center, near Yavoriv, Ukraine, 13 June 2017 (U.S. Army photo by Sergeant Anthony Jones).

Implication 8.1: DoD should expand security force assistance (SFA) efforts through the Army’s Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs), Special Forces (SF) and State Partnership Program (SPP).

The Army’s SFABs, SF and SPP are complementary yet distinct tools for conducting SFA.58 SFABs are the Army’s first purpose-built formation for training partner conventional forces. SF works through indigenous forces and prioritizes training foreign unconventional and SOF forces. SPP partners foreign militaries with U.S. state National Guard units and forms in-roads for deeper engagement.

SFA is an essential tool in strategic competition. As demonstrated in Ukraine, it can build partner capacity in the periphery of a strategic competitor. The Army, DoD and partners could expand these efforts in nations with concerns of Russian territorial aggression, such as Moldova and Kazakhstan (both SPP members). They should also strengthen training engagements with Taiwan—and Washington should consider including it in SPP.

Additionally, Army SFA can responsibly reduce demands on U.S. forces in lower-priority regions. The 2022 NDS emphasizes that the Indo-Pacific is the United States’ priority theater, followed by Europe. Still, threats in the Middle East and Africa require sustained attention, preferably working through local forces. For example, SFABs and SF can train local partners to conduct counterterrorism operations with the “by, with and through” approach that degraded the Islamic State between 2016 and 2019.

U.S. allies and partners can similarly look to expand training efforts. Those less proximate to geopolitical flashpoints may have sufficient capacity to create formations dedicated to SFA. For example, in 2021, the British Army repurposed its 11th Infantry Brigade into the 11th SFAB (the same name as its U.S.-counterpart). Others could expand SOF rotations to create local, territorial defense forces or build partner capacity in lower-priority regions. In either case, relatively limited investments can have an outsized strategic impact.

Observation 9: Ukrainian cross-domain maneuver, albeit episodic, has demonstrated potential opportunities for multi-domain operations on the contemporary battlefield.

The Ukrainian military has demonstrated a limited ability to conduct cross-domain maneuver—what the U.S. Army defines as “the synchronization and employment of forces and capabilities . . . across multiple domains.”59

ISR and fires have made the battlefield in Ukraine highly lethal, exacerbated by detection in the cyber domain and electromagnetic spectrum. Russian forces have massed with easily detectable signatures, creating cross-domain vulnerabilities whereby the electromagnetic spectrum renders its ground forces susceptible to kinetic attack. Ukraine has exploited these vulnerabilities to target fires, notably in the HIMARS strike on a Russian troop dormitory in Makiivka that reportedly killed hundreds.60 Ukraine also conducted a cross-domain fire to sink the Moskva, the flagship of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.61

Implication 9.1: Congress should fund the Army’s two additional planned MDTFs to provide the joint force with enhanced counter anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

That Ukraine has been able to conduct cross-domain maneuver despite its forces not being modernized to do so indicates that formations with the requisite capabilities, such as the U.S. Army’s MDTFs, could pose significant dilemmas to adversaries.

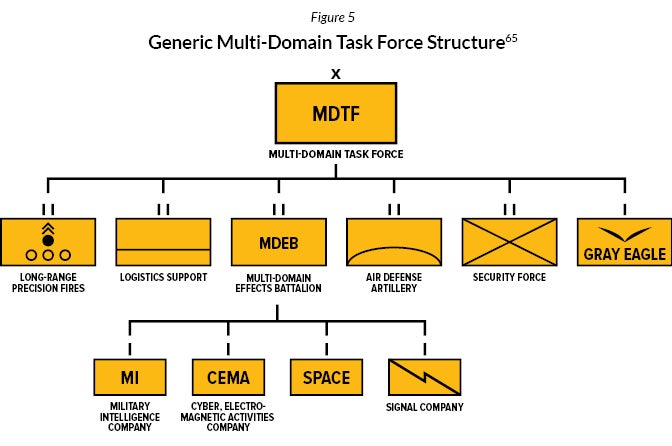

MDTFs are theater-level, multi-domain maneuver elements that synchronize long-range precision effects (LRPE)—such as electronic warfare, space, cyber and information—with LRPF.62 An MDTF maneuvers across domains during competition to gain positions of advantage; in conflict, it provides combatant commanders options to penetrate adversary A2/AD networks.

There has been a high demand from combatant commanders in U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) and U.S. European Command for the capabilities organic to MDTFs.63 Admiral Harry B. Harris, former Commander of Pacific Command, saw the potential for MDTFs to “sink ships, neutralize satellites, shoot down missiles and airplanes and hack or jam the enemy’s ability to command and control.”64

Currently, there are two MDTFs in the Indo-Pacific and one in Europe. The Army plans to stand up a third in the Indo-Pacific and to have another employed globally. Congress should provide the funding for these additional MDTFs over the next one to two fiscal years.

Implication 9.2: Combatant commanders should empower MDTFs to exploit emerging opportunities rapidly.

Survival on the modern battlefield is a function of dispersion, maneuverability and acting quickly enough to disrupt the enemy’s kill chain.66 These elements are essential to MDTF operations, potentially improving their survivability against adversaries’ A2/AD. MDTFs conduct distributed operations and leverage their mobility to avoid adversary fires. Integrating effects and fires can shorten decision timelines, allowing an MDTF to degrade or destroy adversary capabilities before they are employed.

The common factor of these elements of survivability is that the Army and the joint force must empower MDTFs to exploit emerging, time-constrained opportunities. MDO will require decentralized authority, particularly in LSCO with degraded communications. It also necessitates that the Army adapt leader development with a renewed focus on mission command.

Implication 9.3: The Army and DoD should work with allies and partners to position MDTFs within adversaries’ A2/AD networks.

MDTF capabilities—notably LRPF—have the most potential when operating as an “inside force” within adversaries’ A2/AD networks (Figure 6). However, there may be political constraints to basing MDTFs in partner and allied territories, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. These are partner decisions, but the Army and DoD can work to demonstrate MDTFs’ value, building on Japan’s January 2023 agreement to station a U.S. Marine Littoral Regiment on Okinawa.67

Conclusion

The Russia-Ukraine war compels the U.S. military to take stock of its preparedness for large-scale conflict and to act decisively to remedy any shortfalls. In support of the NDS’s core tenets—integrated deterrence, campaigning and building enduring advantages—this Spotlight provides considerations for land forces through the lenses of joint combined arms warfare, strategic responsiveness, materiel modernization and operations. This is undoubtedly an incomplete list, and careful study of the conflict should continue.

Finding any virtue in Russia’s illegal and unnecessary war in Ukraine is challenging, but it may remind Western countries of the diligent effort necessary to maintain deterrence. Political leaders should clearly communicate to their citizens the potential costs of a large-scale war. Without public support, vital military investments to maintain peace will not be sustainable. If there is one clear “lesson” that Western nations can confidently draw from the current war, it should be a renewed commitment to prevent a future one.

★ ★ ★ ★

Charles McEnany is a National Security Analyst at the Association of the United States Army. He has an MA in Security Policy Studies from George Washington University.

Colonel Daniel S. Roper, USA, Ret., is Director of National Security Studies at AUSA. A career Artilleryman, he has commanded in West Germany, Hawaii and the Continental United States, and he is a graduate of the United States Military Academy, the Naval Postgraduate School, and the Advanced Operational Arts Studies War College Fellowship. He served in Afghanistan and Iraq.

- DoD, 2022 National Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 2022), 1.

- The U.S. Army defines large-scale combat operations (LSCO) as “extensive joint combat operations in terms of scope and size of forces committed, conducted as a campaign aimed at achieving operational and strategic objectives. During ground combat, they typically involve operations by multiple corps and divisions, and they typically include substantial forces from the joint and multinational team.” Department of the Army, Army Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 2022), 1-10. The Russia-Ukraine war has not involved “operations by multiple corps and divisions.” Additionally, Russia and Ukraine have not conducted large-scale joint operations, and there have been no multinational operations. Therefore, the conflict does not meet this definition of LSCO.

- FM 3-0, Operations, 1-2.

- John Vandiver, “Get used to wielding ‘hard power,’ US Army general at head of NATO command tells allies,” Stars and Stripes, 10 January 2023.

- John E. Whitley, Underfunding the Army Has Risky Implications, Association of the United States Army, Special Report 23-1, 11 January 2023, 6.

- Whitley, Underfunding the Army Has Risky Implications, 2.

- David E. Johnson, “An Overview of Land Warfare,” Heritage Foundation, 4 October 2017.

- Robert A. Pape, “Bombing to Lose,” Foreign Affairs, 20 October 2022.

- Whitley, Underfunding the Army Has Risky Implications, 1.

- Jim Garamone, “Change Coming to Strategic Levels in Military, Dunford Promises,” DoD News, 5 October 2016.

- Aislinn Laing, Andrea Shalal and Robin Emmott, “U.S. to boost military presence in Europe as NATO bolsters its eastern flank,” Reuters, 29 June 2022.

- Julia Shapero, “Russia lays out plans to boost size of military to 1.5 million,” The Hill, 17 January 2023.

- Frank Hoffman, “American Defense Priorities After Ukraine,” War on the Rocks, 2 January 2023.

- Lieutenant Colonel Amos C. Fox, Reflections on Russia’s 2022 Invasion of Ukraine: Combined Arms Warfare, the Battalion Tactical Group and Wars in a Fishbowl, Association of the United States Army, Land Warfare Paper 149, September 2022.

- Ellen Francis, “Russia has lost nearly half its main battle tanks, report estimates,” Washington Post, 16 February 2023.

- Sam Fellman and Mattathias Schwartz, “Ukraine has destroyed nearly 10% of Russia's tanks, making experts ask: Are tanks over?” Business Insider, 22 March 2022.

- “War Offers Lessons on Russian Military, Warfare,” Association of the United States Army, 17 October 2022.

- Profile of the United States Army, Association of the United States Army, 2022, 24.

- U.S. Army Europe and Africa (@USArmyEURAF), Twitter photo, 14 September 2021.

- Janell Ford, “First-ever division level training rotation at NTC complete,” Army News Service, 14 April 2021.

- Timothy Marler, “Unlocking Training Technology for Multi-Domain Operations,” RAND Corporation, 24 January 2023.

- Strategic Responsiveness: New Paradigm for a Transformed Army, Association of the United States Army, Defense Reports 00-3, October 2000, 1. The Army commonly used the term “strategic responsiveness” in the early 2000s (as such, the definition in this Spotlight is from 2000). In the post-9/11 era, the term’s usage has declined. Today, the concept resembles “strategic readiness,” which the Army defines as “the ability to provide adequate forces to meet the demands of the National Military Strategy.” Department of the Army, Army Regulation 525-30, Army Strategic and Operational Readiness (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 9 April 2020), 2. This Spotlight opts for “strategic responsiveness,” as it better conveys the full range of elements required for Army power projection in strategic competition than the narrower focus on “adequate forces” in “strategic readiness.”

- Angela Dewan, “Ukraine and Russia’s militaries are David and Goliath. Here’s how they compare,” CNN, 25 February 2022.

- Mark F. Cancian, “Russian Casualties in Ukraine: Reaching the Tipping Point,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 31 March 2022.

- Dan Sabbagh, “Ukraine’s high casualty rate could bring war to tipping point,” The Guardian, 10 June 2022.

- U.K. Ministry of Defence (@DefenceHQ), “Latest Defence Intelligence update on the situation in Ukraine - 17 February 2023,” Twitter photo.

- “Russia taken 180,000 dead or wounded in Ukraine: Norwegian army,” France 24, 22 January 2023.

- Mary Ilyushina and Francesca Ebel, “Using conscripts and prison inmates, Russia doubles its forces in Ukraine,” Washington Post, 23 December 2022.

- Hunter Rhoades, “Future Soldier Preparatory Course to expand based on initial success,” Army News Service, 9 January 2023.

- Courtney Kube, “Russia and Ukraine are firing 24,000 or more artillery rounds a day,” NBC News, 10 November 2022.

- Jack Detsch, “Russia Is Running Low on Ammo,” Foreign Policy, 23 November 2022.

- Jamie McIntyre, “Russia claims capture of Soledar as Pentagon says Putin undeterred by heavy battlefield losses,” Washington Examiner, 11 January 2023.

- Seth G. Jones, Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenge to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base, Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 2023, 7.

- Karen DeYoung, Dan Lamothe and Isabelle Khurshudyan, “Inside the monumental, stop-start effort to arm Ukraine,” Washington Post, 23 December 2022.

- Jen Judson, “With demand high in Ukraine, US Army ramps up artillery production,” Defense News, 25 January 2023.

- Jennifer Kavanaugh and Jordan Cohen, “The Real Reasons for Taiwan’s Arms Backlog—and How to Fix It,” War on the Rocks, 13 January 2023.

- Cameron Porter, “Army leaders at AUSA stress importance of Army Prepositioned Stocks program,” Army News Service, 13 October 2022.

- Sydney J. Freedberg Jr. and Andrew Eversden, “Firepower & people: Army chief on keys to future war,” Breaking Defense, 10 October 2022.

- Luke Vargas and Dan Michaels, “How Himars Transformed the Battle for Ukraine,” What’s New, Wall Street Journal, podcast, 10 October 2022.

- Lieutenant General Stephen Lanza, USA, Ret., and Colonel Daniel S. Roper, USA, Ret., Fires for Effects: 10 Questions about Army Long-Range Precision Fires in the Joint Fight, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 21-1, August 2021.

- Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Army Plans To Grow Artillery,” Breaking Defense, 10 May 2021.

- David Hambling, “Russia’s Deadly Artillery Drones Have A Strange Secret,” Forbes, 11 April 2022.

- Marcus Weisgerber, “US Trying to Persuade More Allies to Send NASAMS Missiles to Ukraine, Raytheon CEO Says,” Defense One, 1 December 2022.

- Dan Lamothe and Karen DeYoung, “Biden administration to send Patriot missile system to Ukraine,” Washington Post, 21 December 2022.

- Mark F. Cancian, “Can the United States Do More for Ukrainian Air Defense?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 17 October 2022.

- Michael E. Miller and Anastacia Galouchka, “Ukraine’s drone hunters scramble to destroy Russia’s Iranian-built fleet,” Washington Post, 28 November 2022.

- Jeremiah Rozman, Integrated Air and Missile Defense in Multi-Domain Operations, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 20-2, May 2020.

- Theresa Hitchens, “Army’s IBCS wraps up initial operational testing,” Breaking Defense, 9 November 2022.

- Major General Cedric T. Wins, “CCDC’S road map to modernizing the Army: air and missile defense,” Army News Service, 10 September 2019.

- “Hidden Dangers, Hidden Answers,” CNA.

- Tucker Chase and Matthew Hanes, “There’s a Race for Arctic-Capable Drones Going On, and the United States is Losing,” Modern War Institute, 19 January 2022.

- Andrew Eversden, “Lawmakers push for directed energy weapons, suggest collaboration with Israel,” Breaking Defense, 27 June 2022.

- Mark F. Cancian, “Aid to Ukraine Explained in Six Charts,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 18 November 2022.

- Doug G. Ware, “Ukrainian troops arrive at Fort Sill to train on Patriot missile system, Pentagon says,” Stars and Stripes, 17 January 2023.

- Dan Lamothe, “U.S. begins expanded training of Ukrainian forces for large-scale combat,” Washington Post, 15 January 2023.

- Julian E. Barnes, Helene Cooper and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Intelligence Is Helping Ukraine Kill Russian Generals, Officials Say,” New York Times, 4 May 2022.

- Isabelle Khurshudyan et al., “Inside the Ukrainian counteroffensive that shocked Putin and reshaped the war,” Washington Post, 29 December 2022.

- Charles McEnany, The U.S. Army’s Security Force Assistance Triad: Security Force Assistance Brigades, Special Forces and the State Partnership Program, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 22-3, October 2022.

- U.S. Army Futures Command (AFC), AFC Pamphlet 71-20-2, Army Futures Command Concept for Brigade Combat Team Cross-Domain Maneuver 2028, August 2020, vii.

- “Makiivka strike: what we know about the deadliest attack on Russian troops since Ukraine war began,” The Guardian, 3 January 2023.

- Dan Sabbagh, “US shared location of cruiser Moskva with Ukraine prior to sinking,” The Guardian, 6 May 2022.

- Charles McEnany, Multi-Domain Task Forces: A Glimpse at the Army of 2035, Association of the United States Army, Spotlight 22-2, March 2022.

- Lanza and Roper, “Fires for Effects: 10 Questions about Army Long-Range Precision Fires in the Joint Fight,” 3.

- Admiral Harry B. Harris, Jr., “Association of the United States Army Conference,” virtual speech to the Association of the United States Army Annual Meeting, 4 October 2016.

- Department of the Army, America’s America: Ready Now, Investing in the Future: FY19-21 Accomplishments and Investment Plan, 6.

- Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi et al., Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February–July 2022, Royal United Services Institute, 30 November 2022, 3.

- Joe Gould, “Japan to OK new US Marine littoral regiment on Okinawa,” Defense News, 11 January 2023.

- John Gordon IV and John Matsumura, Army Theater Fires Command: Integration and Control of Very Long-Range Army Fires (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2021), 6.

- Gordon and Matsumura, Army Theater Fires Command, 5.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.