Move, Strike, Protect: An Alternative to the Primacy of Decisiveness and the Offense or Defense Dichotomy in Military Thinking

Move, Strike, Protect: An Alternative to the Primacy of Decisiveness and the Offense or Defense Dichotomy in Military Thinking

by LTC Amos C. Fox, USA

Landpower Essay 23-4, June 2023

In Brief

- Move, Strike, Protect (MSP) offers an agile alternative to organizing for warfare in place of the limiting ideas of offense or defense.

- Decisiveness, as an organizing principle, is an outmoded way of thinking. Therefore, decisiveness should be shelved in favor of ideas more representative of modern war, the resiliency of armies and their states, and of the temporal considerations in armed conflict.

- Attrition, long cast as a type of warfare, is an environmental characterization. Attrition describes operating environments dominated by destruction-oriented warfare. As a result, the process by which Western militaries visualize warfighting must be modified to focus on the intersection of movement and enemy contact. Doing so illuminates the fact that positional and roving warfare are the two primary methods by which combatants engage in armed conflict. As a result, concepts and doctrine must look at how to incorporate those ideas into their respective work to better prepare the force for the future.

Introduction

In the war studies community, the matter of whether the offense or the defense is decisive in war has yet again become a first order question.1 In large part, this is due to Western militaries emerging from the fog of 20 years of irregular conflict against non-state actors. In these post-9/11 wars, large-scale offensive and defensive operations were non-existent, and the dichotomous question of the primacy of offense or defense was irrelevant to their outcomes. To be sure, the U.S. military and its Western partners won nearly every engagement and battle during this period, but they generally failed to obtain their policy aims. One need look no further than the Taliban’s current control of Afghanistan and a fractured Iraq as proof-positive of these failed policy aims.

From the battlefields in Syria to those in Ukraine, modern armed conflict attests to the fact that combatants win or lose wars through attrition. Historian Cathal Nolan clearly summarizes this idea: “We must keep our eyes open to the grim reality that victory [in war] was usually achieved by grinding attrition and mass slaughter.”2 Actors who are incapable of enduring shock and the materiel requirements of long, attritional wars are often those who lose in modern, industrial and technology-laden armed conflict.3

On the other hand, actors who are willing to accept the centrality of attrition are best structured to survive war’s existential crises; they do not suffer surprise at a war’s duration and materiel costs and they persist to achieve their policy aims.4 To be sure, actors with the strategic depth to endure attrition and to stave off the exhaustion of their national bases of power are best oriented to win in war. Or, as scholar Stephen Van Evera succinctly asserts, “War is a trial of strength.”5 Conversely, actors who are purpose-built for quick wins and organized for one feature of warfare over another (i.e., offense or defense) tend to stumble their way through armed conflict and are quickly defeated—or suffer very painful lessons as they work to adapt to the attritional realities of armed conflict.6

Further, scholar Stephen Biddle correctly asserts that, “All warfare poses a trade-off between lethality and concealment.”7 Specializing in either offense, defense or for decisive battle causes one to selectively sacrifice the flexibility required to engage these trade-offs. Instead of specializing, or optimizing for offense, defense or decisiveness, Western militaries should seek out the transcendent features of warfare that are salient to those three features of war. Moreover, in examining decisiveness relative to offense and defense, and the role of offense and defense in warfare, it is important to examine if these terms are still relevant. If so, the veracity of these ideas—decisiveness, offense and defense—as first order and organizing principles for Western militaries must be examined.

In this paper, I submit that decisiveness is largely an irrelevant idea in modern war due to the robust and resilient nature of a state’s armed forces. To be sure, Nolan contends that the pursuit of decisive battle, elevated to the level of “pseudoscientific dogma,” thanks to Carl von Clausewitz and Antoine Jomini, is a fool’s errand.8 Moreover, I contend that the so-called primacy of offense or defense is not the most useful organizing consideration in modern or future war because neither offensive nor defensive action alone brings strategic victory in armed conflict.

Western states should instead organize their military forces around the principle of relentlessly driving an adversary toward strategic exhaustion. Western militaries should accomplish this by possessing the ability to relentlessly iterate through a challenge-response cycle guided by the interplay of three transcendent warfighting activities: move, strike and protect.9 In Ukraine, for instance, the Ukrainian military’s ability to rapidly cycle through movement, striking and protecting—not offensive or defensive posturing—has allowed it to overcome seemingly indomitable odds in the face of Russia’s unprovoked onslaught.10

This move, strike and protect construct, or MSP, is an agile alternative to optimizing around either offensive operations, such as the French military did in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, or defensive operations, such as we saw in the U.S. Army’s Active Defense doctrine of the 1970s.11 MSP transcends the traps associated with being organized, equipped and educated for one type of fighting (i.e., offense or defense) because its dexterity allows it to address the rigors of both offensive and defensive operations. MSP, coupled with the understanding that decisiveness in modern war is ephemeral, and the grim reality of attrition’s centrality to the nature of war, should form the baseline organizing principles for Western armed forces as they look to the future.

Decisiveness: A Spurious Term in Modern War

In political-military parlance, decisiveness in war is the result of military action that directly impacts the military and/or political leader’s intent to continue with a specific policy.12 Put another way, it describes the strategy or policy changes brought about through military activity. Moreover, decisiveness in the political-military sense is the translation of “combat into achievement of an important strategic and political goal that the other side is forced to recognize and accept when the war is over.”13 In effect, a decisive outcome at the political and strategic levels is a victorious outcome, or one that generates a punctuated change in how the opposing actor continues to engage in the conflict. Historian Jim Storr provides perhaps one of the most succinct—albeit germane—definitions of decisiveness in war:

Success and failure are not the same as decision. Something is decisive if it resolves or settles an issue. A campaign that decides a war is strategically decisive. A battle that decides a campaign is operationally decisive. An action that decides a battle or engagement is tactically decisive.14

Ukraine’s victory at the Battle of Kyiv in February and March of 2022, for instance, was tactically and operationally decisive because it forced the Kremlin to reshape its political and war aims. Despite the battle’s decisiveness, Ukraine’s victory did not win the war, but it did create a political and strategic branch for all of the actors who are competing within the conflict.15 As a bonus, Ukraine’s stalwart defense of Kyiv demonstrated to the international community that Ukraine possesses the will to win and that, with additional economic, intelligence and materiel support, they might be capable of militarily defeating Russia.

Historical Origin and Use of the Term

The idea of decisiveness in war originates from the time in which heads of state (and lesser policymakers) accompanied their armies on the field of battle. Historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, for instance, in discussing Russia’s wars during the reign of Peter the Great, stated that Peter was the Russian army’s center of gravity; all political and military decisions started and stopped with the Czar.16 As a result of the proximity of the policymaker to his army, the impact of a battle or engagement on his mind carried outsized importance. A battle or engagement that both rapidly and unquestionably destroyed a policymaker’s army in front of him would force him to make a decision—hence the origination of the term. Policymakers had to wrestle with two basic decisions: one, keep their army in the field and continue to fight; or two, accept the battle’s outcome as the war’s outcome, thus connecting tactical success or failure directly to strategic and/or political victory or defeat.

The ostensible importance of decisiveness is an enduring effect of Carl von Clausewitz and Antoine Jomini’s documentation of Napoleon Bonaparte’s battlefield brilliance. The Battle of Austerlitz, from the Napoleonic Wars’ War of the Third Coalition in 1805–1806, is a case in point. This battle, often referred to by historians as the “Battle of the Three Emperors,” resulted in Bonaparte’s army making short work of Russian and Austrian forces.17

Although several smaller polities participated in the War of the Third Coalition, France, Austria and Russia were the primary players.18 Bonaparte sat atop France’s Grande Armée. Czar Alexander and his brother, Grand Duke Constantine, commanded Russian forces in the field. Francis I, Emperor of Austria, led his state’s forces in the contest. Bonaparte’s blistering battlefield victory on 2 December 1805, a classic from the annals of military history, imprinted the perceived importance of decisiveness in armed conflict on the minds of those who study war, projecting a sense of its importance forward even to today.19

What Clausewitz, Jomini and most modern analysts and practitioners miss, however, is the interdependence of decisiveness on both the physical presence of the head of state on the battlefield and on the outcomes of the battle and war. This lapse is forgivable regarding Clausewitz and Jomini because the presence of the relevant heads of state on the battlefield was a given feature of war in their day; today however, that is not the case. In fact, it was during the Battle of Solferino in the Second Italian War of Independence (24 June 1859) that heads of state are last known to have directly commanded their armies in the field.20

Application of the Term in the 20th Century and in the Recent Middle East

Despite the significant passage of time and evolved and evolving methods of war over the past 200 years, modern analysts and practitioners have failed to inquire about the continued relevance of this term—i.e., decisive. Instead, they hammer on, using outmoded adjectives and ideas from 200 years ago to describe war and warfare today. Old ideas are fine when they remain relevant, or when they provide the context needed to understand the situation regarding current events. But adherence to irrelevant ideas—ideas wielded like a broadsword against a tank—demonstrates both institutional recalcitrance toward modernizing military thinking and cognitive laziness.

In modern war, in which states possess redundant and adaptive systems, as well as an array of active and tacit partners, decisiveness is rarely an important adjective at the operational and tactical levels. This idea is not new, but it is often forgotten. Noting this feature, J.F.C. Fuller wrote in 1926 that wars are no longer duels between armies; rather, wars are struggles between states, and, in turn, states must orient warfighting on generating strategic exhaustion and collapse in one’s opponent.21 He recognized this almost one hundred years ago.

Currently, decisiveness at the operational and tactical levels generally aligns with winning a campaign, operation or battle. Storr offers that, “The key to battlefield (and hence operational) success appears to be to apply violence in such a way as to convince senior enemy commanders to desist.”22 While winning matters, the cumulation of operational and tactical success does not necessarily correlate to political and strategic victory. To be sure, the United States scored an unabashed military victory against the Taliban in Afghanistan in late 2001. But that victory, as well as innumerable decisive engagements during the following 20 years of war, had limited impact on turning those small, decisive wins into strategic or political victory for the United States. The war in Afghanistan demonstrates that, in effect, tactical and operational decisiveness can often be strategically and politically irrelevant.

Likewise, the U.S. military racked up several stunning tactical successes during the outset of Operation Iraqi Freedom, but those successes turned the course of the war on its head.23 In the wake of the U.S. coalition’s decisive operational and strategic victories in Iraq in the spring of 2003—rapid defeat of the Iraqi military and the toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime—a phase change occurred. The Iraqi people were generally unwilling to accept the outcome of the U.S.’s operational success. The war in Iraq, like the one in Afghanistan, demonstrates that, in effect, decisiveness can be strategically and politically irrelevant.

Decisiveness in Ukraine and Contemporary Warfare

Moving beyond these American wars to more recent armed conflict, Russia decisively won the operations to control Kherson and Mariupol in early 2022 during the on-going Russo-Ukrainian War.24 Yet, a short time later, Ukraine retook Kherson, obviating the relative significance between Kherson, decisiveness and the war’s outcome.25 Nonetheless, those operational victories are unlikely to carry significant strategic weight beyond extending the war’s duration as Kyiv grinds toward retaking its occupied territory. The idea of decisiveness, represented in the Russo-Ukrainian War thus far, is merely a hollow, temporal effect, bearing little impact on expediting the war’s conclusion.

Viewed from a realistic and unemotional lens, the so-called logic of decisiveness, in this day and age, is no longer valid. Heads of state have not led their forces in battle in well over a century and a half, meaning that catastrophic military defeats no longer carry the political significance that they did in the past. As a result, the term decisive should be set aside and no longer centrally featured in Western military language. Moreover, a single engagement or battle rarely has a direct and immediate strategic or political impact on the course or the outcome of a war. Modern militaries are not brittle, self-contained organisms prone to shock and isolation, as they were during preceding eras of armed conflict. Instead, modern militaries are led in the field by a cadre of officers trained and educated to pragmatically pursue victory, not to stumble into a strategically existential situation. Modern militaries are the expression of self-interested states that possess complex and adaptive political, domestic, economic and industrial bases from which to advance their respective national interests.

When an actor achieves decisiveness in modern armed conflict—that is, imposing a military or political-military decision on an adversary—that decisiveness is a temporal and fleeting condition. Though so-called “decisive action” may initially seem to effect shorter and less expensive conflicts, especially as opposed to strategic exhaustion, which sounds long and costly, the latter is supported by fact, while the former is aspirational and generally ahistorical in modern armed conflict. As a result, optimizing for future armed conflict around the idea of decisiveness is a fool’s errand. In decisiveness’ place, optimizing for future armed conflict should rest on generating forces that can dominate an unflinching challenge-response cycle that iterates until its opponent is strategically exhausted. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Modern Western military doctrine compounds the problems associated with the use of the term decisiveness. Western military doctrine muddies it by equating its use to mission accomplishment, further sanding off the nuance of positive change associated with the concept’s theoretical underpinnings.26 Moreover, a quick scan of the U.S. Army’s Field Manual 3-0, Operations, for instance, yields several unhelpful variational uses of decisive: decisive points, decisive engagements, decisive spaces, decisive battle, decisive operations, decisive (as a method), decisive campaign, decisive resolution, decisive factor, and decisive victory.27

The use and abuse of the term (and its many variant forms) provides no clarifying meaning to the words to which it is attached in contemporary doctrine and analysis. This, coupled with its temporal character in modern war, means that its use provides almost no value regarding how to optimize for armed conflict. Arguably, Western governments and militaries would be better served removing the term from their lexicons altogether and using a term or phrase which describes what they actually intend to accomplish with military action.

Offense and Defense—A False Dichotomy

French military history provides a useful lesson for thinking about strategic alignment with the offense or the defense. The French came into World War I strategically aligned—that is, organized, equipped, trained and doctrinally oriented—for the offense. Elan vital and the cult of the offensive were terms openly used within the French military to describe this strategic posture and optimization.28

Yet, this French elan and the spirit of the offense struggled to overcome an adaptive Germany, which developed innovative methods, such as infiltration tactics, as well as operations, such as its elastic defense-in-depth, to offset and overcome French optimization for the offense.29 The pragmatic challenge-response cycle between France and its allies, and Germany and its allies, turned the promise of a short and decisive war into a long, attritional and destructive slog that cost the French a generation of men.30

Coming out of World War I, the French military reorganized for defense.31 The Maginot Line is perhaps the best-known illustration of France’s defensive mindset.32 When Germany invaded France in May 1940, it took the German military little more than six weeks to defeat the defense-oriented French military.33 Given this overemphasis on defense, the plight of France in both World Wars illustrates the weakness of being overly invested in one area rather than investing in an adaptive approach.

In both wars, France overemphasized military orientation toward one end of the offense-defense spectrum. In doing so, its military became more, not less, vulnerable to a pragmatic opponent fiendishly interested in political victory. And, despite France ultimately being on the victorious side in both wars, its experience in international armed conflict during the 20th century represents a cautionary tale regarding optimizing for offense or defense rather than optimizing in a more pragmatic way.

Pragmatic Alternatives to Offense or Defense Optimization

Cathal Nolan persuasively argues that strategic actors do not win wars through offense- or defense-oriented militaries but through fielding militaries that can weather the rigors of destructive combat and outlast their opponent.34 Put another way, strategic exhaustion is the path to victory in war. Bonaparte clearly realized this, emphatically stating: “The whole art of war consists in well-reasoned and extremely circumspect defensive, followed by rapid and audacious attack.”35 Therefore, when thinking about how to optimize a military, strategists’ focus should not be on offense, defense or decisiveness, but rather on how the military can be used to push an opponent to strategic exhaustion through iteratively cycling through challenge-response opportunities.

Starting at the top, and working toward the tactical end of things, militaries should optimize to consume an opponent’s strategic depth—i.e., industrial base, human capital, strategic transportation, and political and domestic support—because doing so is the most reliable way to bring a political opponent to the negotiation table. At the operational and tactical levels, a military must be optimized to relentlessly fight and destroy a pragmatic opponent that is trying both to survive and to accomplish its own political-military goals. In short, military forces must be optimized to withstand and win long, destructive wars. These long and destructive wars are not won by being better at offensive or defensive operations. Equally important, they also are not won by being optimized for offense ahead of defense, or vice versa. Instead, iteratively and skillfully moving, striking an enemy and protecting oneself and one’s interests, for as long as it takes, are the keys to unlocking political victory in such wars.

Therefore, given the false dichotomy between offense or defense, and the general irrelevance of decisiveness in modern war, how does a military optimize for attritional wars in which it must endlessly cycle through offensive and defensive operations until it achieves political victory? To answer this question, one must find the principles of warfighting that transcend both offensive and defensive operations.

Organizing Principles

Move, Strike and Protect: Moving Beyond Banal Dichotomies

Based on armed conflict’s attritional nature, force optimization must start with organizing and equipping to account for destruction and battlefield losses. Arguments that the future of conflict will be any less deadly or destructive are out of touch with reality, are borderline delusional and are in no way supported by much more than wishful thinking. Forces must therefore be constructed with the capacity required to absorb casualties and equipment losses. Force structure should be optimized around the ideas of elasticity, redundancy, mobility and localized overmatch.

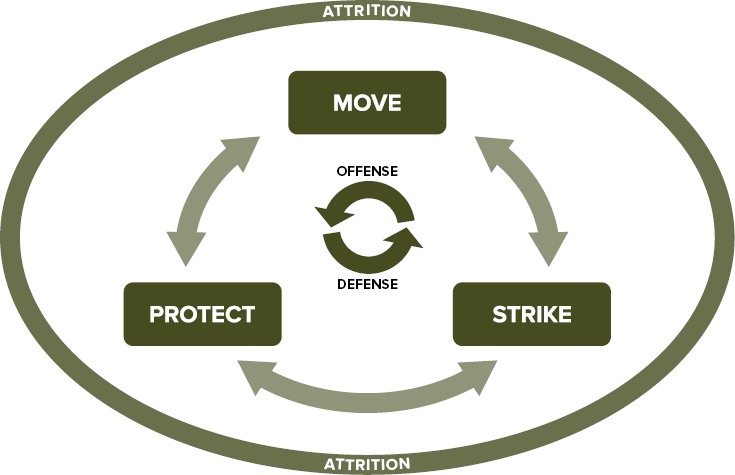

From a method of warfighting standpoint, three primary ideas transcend both offensive and defensive operations while simultaneously accounting for the attritional nature of armed conflict: move, strike and protect (MSP). In armed conflict, whether an actor finds himself on offense or defense, forces must be optimized for MSP. Not only do these principles transcend offense and defense, but they are equally relevant at the strategic, operational, tactical and micro-tactical levels of armed conflict. States must possess MSP capabilities across strategic, operational and tactical distance. Military forces at all levels of war, on the other hand, must be able to move, strike their opponent(s) and protect themselves. (Figure 2)

Figure 2

From a pragmatic point of view, the principles outlined above are universal. The Western world’s strategic competitors, to include China and Russia, approach armed conflict in a similar way. Reflecting that duality, Western military forces must also optimize to counteract a strategic competitor’s MSP capabilities at the strategic, operational and tactical levels of war. Thinking about war in this way provides a more relevant and useful framework for optimizing for armed conflict than does an “offense-or-defense” dichotomy because armed conflict’s attritional nature causes the repetitive cycling through both offense and defense—until a conflict concludes.

Organize and Optimize for Attrition: What Attrition Warfare Is and Is Not

This section closes with a brief note about attrition. In short, it is an idea that is vastly misunderstood because of decades of being misrepresented in war studies literature and in Western military doctrine. Attrition is not a form of warfare, nor is there a set of specific tactics specifically linked to it.

Attrition is a descriptive term for battles, campaigns, operations or wars in which high levels of destruction occur. In attritional environments, both actors can be subject to high levels of destruction, or one actor can inflict high casualties on the other. In either case, a military force striving to destroy a significant amount of the enemy’s combat power, to advance the enemy toward strategic exhaustion, is not simultaneously allowing the same thing to happen to itself. Thus, arguments against attrition suggesting that destruction-oriented operations have a reciprocal impact on oneself are unconvincing strawmen that do not hold up to rigorous examination.

Moreover, attrition is a fundamental feature both of war and warfare. As a fundamental feature, and despite the Clausewitzian school of thought’s opposition to additions, attrition is a salient component of the nature of war. As a fundamental feature of war, attrition is justified as an organizing and optimization principle for Western military forces.

Organize and Optimize for Position and Roving

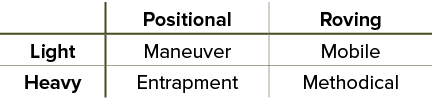

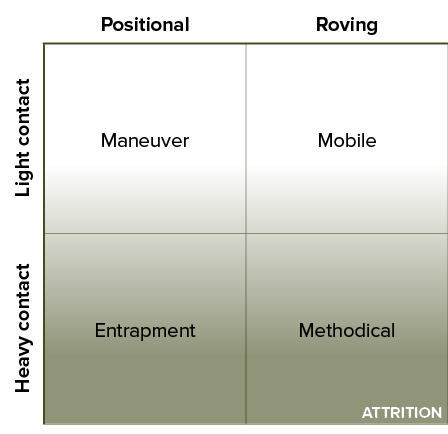

An alternative way to think about land and joint warfare, instead of the unhelpful maneuver-attrition dichotomy, is through roving and position. Roving is linearly oriented tactics and operations. Roving warfare is the use of movement and situationally dependent levels of destruction, from point A to an objective at point B. Positional warfare is when the tactics and the operations are oriented on something relatively close, taking a relatively local piece of terrain, or military force, either enemy or friendly; it uses movement to accomplish its objective.

Light and heavy contact must be cross-threaded against roving and positional thinking. In some instances, a military force must use heavy contact (i.e., direct and indirect attacks) and must focus less on moving quickly to adequately support its operation. Conversely, some situations require a small degree of direct and indirect attacks against an enemy and more focus on rapid movement. Viewed collectively, these four variables create a simple methodical taxonomy for tactics and operations: positional tactics and operations with light direct and indirect attacks are maneuver; positional tactics and operations with heavy direct and indirect attacks are entrapment tactics and operations; roving tactics and operations with light contact are mobile tactics and operations; and roving tactics and operations coupled with heavy contact are methodical tactics and operations. (Figure 3)

Figure 3

As the model illustrates, attrition is not a form of warfare. Instead, attrition is a state of being, and a characterization of war in which high casualties as a result of significant direct and indirect attacks occur. (Figure 4). Moving forward, Western militaries should improve their optimization for war by discarding maneuver-centric thinking and their denigration of attrition; they should instead embrace the maneuver-entrapment-mobile-methodical construct. This model, working in concert with the MSP construct, will provide Western militaries with thinking that is better grounded in the realities of war—rather than swimming in a pool of antiquated and bankrupt concepts.

Figure 4

Conclusion

As Western militaries set out to reorganize and optimize for the future, they must not fall into the rut of routine thinking. They must challenge the orthodoxy of institutional thinking and must challenge the bias injected into military thinking by the individuals whom they rely on for innovation. This innovation, another phrase for optimizing for the future, cannot be crowdsourced. Crowds are good for finding a few nascent ideas, but if the legwork of innovation is a populist affair, the output will be a milquetoast product that reeks of bureaucratic language and self-bias resistance.

Addressing how to optimize for future armed conflict is the first step in the innovation process. Western militaries must continue to examine if the way in which they are framing the future is most advantageous, based on what is known about the course of events. Further, Western militaries must reflect on whether their ideas and language are inducing cognitive bias toward thinking clearly about the future.

In this paper, I have attempted to address these problems by directly challenging the orthodoxy of the offense or defense dichotomy currently resonating through Western military thinking, as well as by disproving the usefulness of decisiveness in modern and future war. Alternatively, I suggest that Western militaries must optimize for the future by placing attrition as a central organizing principle within their optimization efforts. Next, decisiveness must be removed from the equation and replaced with an iterative challenge-response mechanism. Further, the offense or defense question must be brushed aside; this is because, in armed conflict, both are of equal importance. In their place, Western militaries must optimize around the ability to move, strike and protect, which is a transcendent element operating at a place of higher importance than offense or defense. Finally, the false dichotomy of attrition or maneuver must be brushed aside and replaced with a framework that places positions and vectors at its heart, providing practitioners with a more useful set of tools for optimizing for the future of armed conflict.

To effectively compete, Western military thinking needs to evolve: it needs to develop new ideas for how to organize and fight. It must develop new terms for these ideas, terms that adequately express the ideas associated with the new concepts. It does not benefit anyone to continue interposing worn out and irrelevant terminology and concepts into novel problems in war and warfare.

★ ★ ★ ★

Lieutenant Colonel Amos C. Fox is an officer in the U.S. Army. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Reading (UK), Deputy Director for Development with the Irregular Warfare Initiative, and an associate editor with the Wavell Room. He is also a graduate from the U.S. Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was awarded the Tom Felts Leadership Award in 2017.

- David Johnson, “Ending the Ideology of the Offense: Part I,” War on the Rocks, 15 August 2022; David Johnson, “Ending the Ideology of the Offense: Part II,” War on the Rocks, 25 August 2022.

- Cathal Nolan, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 577.

- Michael O’Hanlon, Military History for the Modern Strategist: America’s Major Wars Since 1861 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2023), 317–319.

- Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conflict (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 257.

- Van Evera, Causes of War, 14.

- O’Hanlon, Military History for the Modern Strategist, 317–319.

- Stephen Biddle, Nonstate Warfare: The Military Methods of Guerillas, Warlords, and Militias (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021), 293.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 575.

- Robert Leonhard, Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of Command (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishing, 1994), 12–31.

- Arthur Schnell, “Invasion,” Doomsday Watch: The Ukraine War (podcast), 2 May 2023.

- Jeffrey Long, “The Evolution of US Army Doctrine: From Active Defense to AirLand Battle and Beyond,” Master’s Thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (1991): 5–6; 30–33.

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Foundations of the Science of War (London: Hutchinson and Company, 1926), 39–41.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 572.

- Jim Storr, The Hall of Mirrors: War and Warfare in the Twentieth Century (Warwick, England: Helion and Company), 255.

- James Marson, “The Ragtag Army That Won the Battle of Kyiv and Saved Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, 20 September 2022.

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Romanovs: 1613–1918 (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2016), 66.

- David Chandler, The Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 36.

- Alexander Mikaberidze, The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 270.

- Mikaberidze, The Napoleonic Wars, 210–212.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 204–207.

- Fuller, The Foundations of the Science of War, 313.

- Storr, The Hall of Mirrors, 193.

- Lawrence Freedman, Command: The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 427–433.

- “Ukraine Conflict Updates,” Institute for the Study of War, 15 August 2022.

- “Ukraine Conflict Updates,” Institute for the Study of War.

- Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2022).

- FM 3-0, Operations.

- Azar Gat, A History of Military Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Cold War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 402–440.

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Conduct of War: 1879–1961 (New Brunswick, NJ: De Capo Press, 1961), 151–182.

- Jeremy Black, Military Strategy: A Global History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020), 165–180.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 409–410.

- Basil Liddell Hart, History of the Second World War (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky and Konecky, 1970), 67–69.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 439.

- Nolan, The Allure of Battle, 1–5.

- Fuller, The Foundations of the Science of War, 335.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.