Modern Problems Require Ancient Solutions: Lessons From Roman Competitive Posture

Modern Problems Require Ancient Solutions: Lessons From Roman Competitive Posture

Introduction

At varying times and with varying validity, Byzantium, the Holy Roman Empire and Russia have all been compared to the Roman Empire or called its successor. The United States is the only modern comparison. Rome was a global power with a Parthian regional rival. The United States is a global power with Chinese and Russian regional rivals. Rome had client states. The United States has formal allies. Rome and the United States each controlled or control the most powerful and effective—though significantly, not the largest—military forces of their times. Despite a well-earned reputation for violence, Rome’s longevity was not due to its ability to use military force.1 At its peak, Rome was successful because it used military force to shape its adversaries’ perceptions in order to magnify Roman military strength.2

Competition is a fundamental aspect of international relations. In competition, states use a mixture of the elements of national power to achieve strategic advantage below the level of armed conflict.3 Because it mostly exists below the level of armed conflict, competition is fundamentally informational. Military operations in peace and war can have a major impact on the information environment, but they are costly. This cost means that successful competition over the long term requires extracting maximum competitive benefit from minimal military force.4 The United States can benefit from studying three ways that Rome did this: guaranteeing its own operational reach, creating effective coalitions and ensuring complementarity and interoperability with its coalition partners.

Avoiding Strategic Culmination

As states’ territories grow, so do their interests.5 This shrinks the geopolitical map and brings those states into direct competition with potential adversaries.6 The wider ranging a state’s interests are, the greater the effort and expense that must be invested in securing them. This creates a sort of internal, bureaucratic security dilemma for the expanding power.7 As the state’s territory expands, so do its interests. This requires it to expand its security apparatus, giving the state the ability to expand its territory and interests further and requiring further growth of the security apparatus.

“Expanding the security apparatus” frequently means expanding a state’s military force—its ability to use its military “by direct application on the battlefield or through active, noncombat deployments.”8 However, military force is a physical phenomenon and is therefore subject to physical limitations. First, distance matters—for military force to be relevant, it must be close. An armored division, no matter how powerful, is not threatening if it is on the other side of the world. Second, cost matters—military force is consumed in use, and therefore expensive. War, and preparing for it, consumes and destroys the “material and moral resources needed to keep fighting.”9 Beyond a certain point, consumption and destruction become greater than the marginal gains of employing force. This is the strategic culminating point.

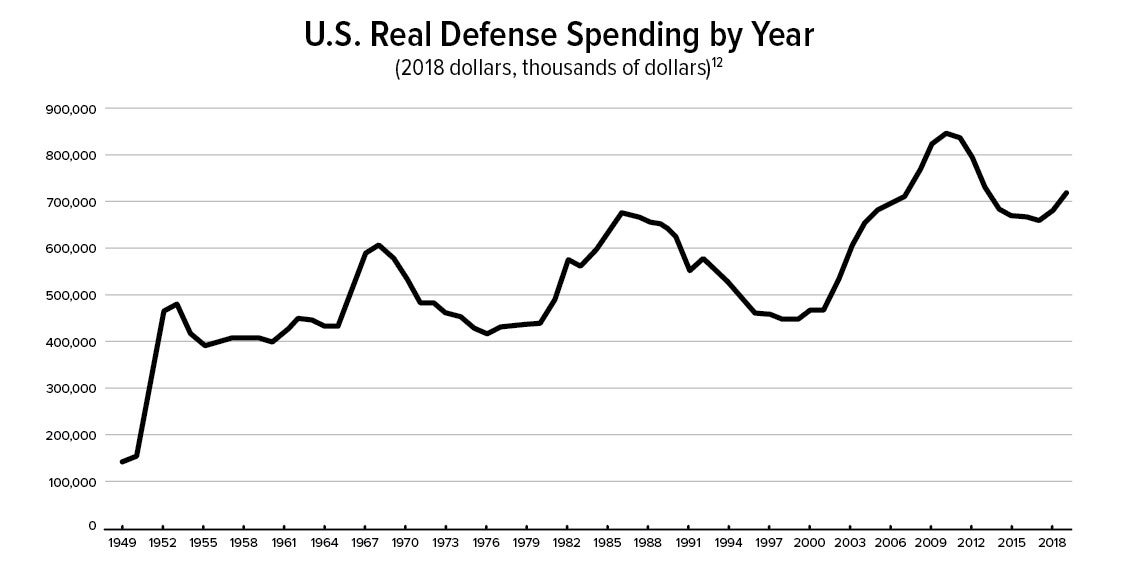

As the character of war changes, states take different approaches to expanding their security apparatus in order to stave off strategic culmination. Ancient warfare was labor intensive, and so Rome staved off culmination by expanding its labor pool, in particular by lengthening enlistment terms. While the Roman city-state was expanding inside Italy, Roman soldiers commonly mobilized for one or a few campaigning seasons before demobilizing. By the time of the Punic Wars with Carthage, Rome had interests around the Mediterranean basin. It was common for Roman citizens to serve six or seven years consecutively, and the state could require their service for up to twenty.10 In contrast, modern warfare is capital intensive, and the United States has sought to stave off culmination by increasing military spending. Following the end of the Cold War in 1991, the lack of a pacing threat allowed the United States’ interests to expand unchecked. Real military spending, primarily on exquisite systems and highly-trained personnel to operate them, has generally followed (see below).11

To avoid strategic culmination, states must project military power, not mere military force.13 Military power is an indirect use of military force to elicit a response from an adversary.14 In other words, military power relies on the perception of force, not its reality. Military power, based as it is on perception rather than reality, relies on knowledge rather than physicality, and knowledge, unlike military equipment and supplies, is neither consumed nor destroyed when used. Military power is therefore far more economically sustainable in the long term than military force.15 These features indicate that states that anticipate enduring competition would benefit from maximizing military power rather than military force.

Military power is the primary input to deterrence. Deterrence is a strategic concept based on persuading adversaries not to initiate an action because they perceive the costs to be greater than the benefits.16 Though any or all elements of national power can be used to deter, the military element is the most effective.17 Because it seeks to shape the perception of adversaries, deterrence, like military power, exists to a large degree in the information domain and is also relatively economical.

How a state balances military force and military power, and how it chooses to use those things, are important questions of grand strategy, “the level at which…intelligence and diplomacy…interact with military strength to determine outcomes in a world of other states with their own grand strategies.”18 During its existence, Rome pursued several grand strategies. The one it pursued when it was a hegemonic empire—the late Republic and early Empire, roughly from 60 BC to 68 AD—is the most analogous and relevant to today’s United States.19

Invest in Operational Reach

The first way Rome used information to magnify its military force and deter adversaries was by guaranteeing its operational reach, “the distance and duration across which a joint force can successfully employ military capabilities.”20 In 23 AD, Tacitus wrote of 25 legions, about 300,000 troops including auxiliaries, spread from the English Channel to the Black Sea and around the Mediterranean.21 With small numbers and a large perimeter, the Roman military did not have sufficient force to be near all adversaries, all the time, and so could not rely on military force. Rather than pursue a dramatic military expansion, Rome shaped its force and its physical geography to create operational reach and therefore maximize the perception of its power.

First, Rome postured and employed its legions to maximize their power. Many legions were stationed in high-threat areas, such as on the Rhine River and in the Near East (modern Lebanon, Syria and Israel).22 This ensured major forces were near the Germanic tribes and Parthia, Rome’s biggest threats, and were able to quickly meet those threats on the battlefield. However, Rome did not employ the legions in a preclusive defense. They were mobile strike forces, able to quickly redeploy anywhere in the empire to meet any threat.

Second, Rome shaped its geography to maximize the power of its legions. The Romans built a vast and famous road network to enable their forces to redeploy rapidly anywhere in the empire. All-weather roads vastly improved marching speed, providing the ancient world’s equivalent of operational reach. This speed turned force into power; because Roman legions could move far more rapidly than contemporary armies, they always felt close to their adversaries, regardless of their location. Rome’s operational reach shaped its adversaries’ perception of the strategic environment, greatly magnifying the impact of its relatively small force.

Today, the United States employs 2.5 million servicemembers, about half of whom are in the active force.23 If that force were fully mobilized for a long period, it would probably be unsustainably expensive. Unlike Rome, the United States stations most of its forces in the homeland rather than on the periphery, though this is slowly changing.24 Because it keeps its forces primarily at home, the United States is heavily reliant on air and sea corridors, the modern analogues to the Roman road network, to translate force into power. Ensuring access to these corridors, and from there to future battlefields, requires pedestrian but necessary capabilities such as transport aircraft and ships. Unfortunately, these capabilities are under-resourced.25

Recent Chinese and Russian activities indicate they doubt American ability to deploy with sufficient speed and mass to prevent them from achieving their goals. To capitalize on this, they have created additional hurdles for American military forces, including A2/AD networks, “salami slicing” strategies and frozen conflicts. All are aimed at aggravating American difficulties in getting to the battlefield.26 Investing in the posture and capabilities to change that perception must be the first focal point of American competitive strategy.

Compete Alongside Allies and Partners

The second way Rome used information to magnify its military force and deter adversaries was through its alliance system. Alliances are primarily diplomatic creations, but like military power and deterrence, diplomacy is primarily informational: it is the intersection of information and persuasion.27 Roman diplomats used threats, coercion, payments and occasionally regime change to create a ring of reliable client states on its periphery. One of the most important services the clients provided was maintaining local security. Rome expected its clients to be strong enough to control their territory, and by extension secure Roman territory, against all but the highest intensity threats. Even in those cases, the clients were expected to delay adversaries as long as possible to allow the Romans to bring forces to bear from across the empire. However, client forces were never allowed to be so strong that the clients themselves were threats to Rome.28 To strike this balance, Rome ensured that its military force was stronger than any single client. As a result, when nearby legions redeployed to face a new threat, the client states were able to protect Roman territory but posed little threat to the now-lightly defended Roman borders. Notably, this did not apply where Roman client states were weak or nonexistent—the Rhine River and the Near East. In these locations, the Romans maintained substantial forces of their own.

Since 1945, the United States has built a similar alliance system to maintain its periphery, especially in Europe and East Asia. Though American allies are far from client states, they could fill a similar, mutually-beneficial role in American security. For instance, American allies are often willing and able to manage local threats when American forces deploy for large-scale operations. In many cases, they have been doing so for decades. For instance, as the United States rotated increasing numbers of Soldiers to Vietnam from 1962 to 1970, it correspondingly reduced the number of its Soldiers in Europe.29 During this time, the defense of Central Europe against the Soviet Union relied on a Euro-American strategic bargain: Europeans would maintain sufficient force to deter the Soviets in peacetime and oppose them in wartime, and Americans would share in the risks of nuclear war.30 This bargain was effectively the same as the Roman one, with American forces, especially nuclear ones, filling the role of Roman legions. Using diplomacy to create coalitions capable of controlling their territory, deterring low-severity threats and delaying high-severity ones reinforces a future American deterrence-based strategy at little direct cost to the United States. Maintaining these alliances must be the second focal point of American competitive strategy.

Integrate Security Capabilities

The third way Rome used information to magnify its military force and deter adversaries was by integrating its military capabilities with those of its client states. Rome’s client states provided auxiliary troops that expanded Roman military force. These auxiliaries were usually employed at about a 1:1 ratio with legionaries, but they did not merely double the force available to Roman commanders.31 Client forces provided capabilities that the Romans did not habitually maintain, each client according to its local specialty.32 For example, legions were almost exclusively heavy infantry, but they regularly employed and operated alongside archers and slingers from Mediterranean client states and cavalry from African ones. Further, particular auxiliary units tended to remain with the legion they supported, probably establishing habitual relationships that made the total force more effective in combat.

That American and allied capabilities are not yet thoroughly integrated is an opportunity for the future of American grand strategy. The F-35 program, for all its faults, is an important step in creating such capabilities.33 Expanding lethal military force is not the only approach though. For example, few NATO members spend the treaty-mandated 2 percent of their GDP on defense, and much of what is spent goes toward maintaining units that are similar to, but less capable than, American ones. Rather than push the relatively arbitrary 2 percent spending target, the United States should encourage its allies to focus on capabilities that are complementary and interoperable with American ones, according to those allies’ comparative advantages.34 For example, the Estonian army is a single infantry brigade, a force unlikely to deter future Russian aggression. However, Tallinn is home to NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence, in part because it has, since 2007, successfully resisted politically-motivated Russian cyber-attacks.35 Estonia’s 2 percent target would probably contribute more value to NATO and the United States if it were used to maximize its cyberwar capabilities than if it were used to maintain a tiny army. Such a bargain would require that American forces be deployed to Estonia in perpetuity. Even that would have a salutary effect though—namely, contributing to re-creating the forward presence the United States has largely ceded since 1991.

Nor must spending be military-focused to be effective. For example, Western European allies, further from direct confrontation with Russia than the Baltic states, might meet their spending goal by building, expanding, improving and/or hardening dual-use infrastructure such as air and seaport facilities and rail and road networks. In peacetime, these infrastructure improvements would have economic, social and environmental benefits. In the event of war with Russia, such facilities would increase the speed with which American forces could deploy, magnifying American military force. In addition, in some states these options may be more politically feasible than expanding the military. For example, because of its history, Germany may find it easier, domestically and internationally, to expand its dual-use infrastructure than to expand its military force.

Such options combine American military force with the information and persuasion of American diplomacy to magnify the perception of American military power in the eyes of its regional rivals. Even better, they cost the United States little or nothing. Pursuing, and encouraging allies to pursue, complementary and interoperable capabilities must be the third focal point of American grand strategy.

Conclusion

To defend their interests without reaching a strategic culminating point, large states such as the United States must rely on deterrence to minimize the expense associated with maintaining and using military force. Deterrent strategies operate in the mind of the adversary, using the information environment to magnify relatively small military force into great military power. The early Roman Empire followed just such a strategy from about 60 BC to 68 AD. It rested on three pillars: operational reach, building coalitions and military integration with its coalition partners. In turn, each of these pillars was founded on Rome’s ability to shape the information environment. American grand strategy should be informed by those lessons, as well as one final lesson: remembering that peripheral territories and interests are just that—peripheral. Starting in about 68 AD, the Romans gradually transitioned from a hegemonic empire to a territorial one by turning their former clients into imperial provinces. This tied Roman domestic political legitimacy to absolute security of its borders. In turn, this eliminated all strategic depth, forcing Rome to pursue a grand strategy based on a static, preclusive defense rather than a mobile, deterrence-based one.36 An unwillingness to discriminate between vital, important and peripheral interests; the imperative of absolute territorial integrity; and the associated increase in the cost of military forces contributed to the empire’s instability and eventual fall in 476 AD.

★ ★ ★ ★

Major John Dzwonczyk is an FA59 Strategist assigned to Joint Task Force-North. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy and Pennsylvania State University. His previous assignments include deployments as a Logistics officer to Iraq, Haiti and Afghanistan; command of a Distribution Company; and as an Assistant Professor of Geography at USMA.

1 Alvin H. Bernstein, “The Strategy of a Warrior State: Rome and the Wars against Carthage, 264–201 BC,” in The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States, and War, 16th ed., ed. Williamson Murray, MacGregor Knox and Alvin H. Bernstein (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

2 Edward Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

3 Department of Defense, Joint Doctrine Note 1-19 Competition Continuum, 3 June 2019.

4 Office of the Undersecretary of Defense (Comptroller), Defense Budget Overview: United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Request, March 2019.

5 Bernard Brodie, “Vital Interests: What Are They, and Who Says So?” in War and Politics (New York: Macmillan and Company, 1974).

6 Robert D. Kaplan, The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us about Coming Conflicts and the Battle against Fate, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 2012), Chapter 8.

7 John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (1950): 157–80.

8 Edward Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the First Century AD to the Third (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 196.

9 Edward Luttwak, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2001), 57.

10 Bernstein, “Strategy of a Warrior State,” 60.

11 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” accessed 14 September 2020, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex.

12 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” Data from the United States, 1949–2019.

13 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 197.

14 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 197; Luttwak, Strategy, 157.

15 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire.

16 Robert A. Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 12.

17 Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Still Do Not Work,” International Security 23, no. 1 (1998): 76.

18 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, 409.

19 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 22–23.

20 DoD, JP 5-0, Joint Planning, 16 June 2017, iv–35.

21 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 17.

22 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 17.

23 Defense Manpower Data Center, DoD Personnel, Workforce Reports & Publications, August 2019.

24 Kyle Rempfer, “Army Resurrects V Corps after Seven Years to Bolster Europe,” Army Times, 12 February 2020; Andrew Gregory, “Maintaining a Deep Bench: Why Armored BCT Rotations in Europe and Korea Are Best for America’s Global Security Requirements,” Modern War Institute, 31 July 2017.

25 Elee Wakim, “Sealift Is America’s Achilles Heel in the Age of Great Power Competition,” War on the Rocks, 18 January 2019; “Activation Exercise Reveals Challenges Facing U.S. Sealift Fleet,” The Maritime Executive, 31 December 2019; Jobie Turner, “Underpinning Asymmetric Advantage: USAF Airlift When Strategic Mobility Is at Risk,” Logistics in War, 17 October 2017.

26 David Perkins, “Multi-Domain Battle: Joint Combined Arms Concept for the 21st Century,” ARMY Magazine, 14 November 2016; Michael Mazarr, “Struggle in the Gray Zone and World Order,” War on the Rocks, 22 December 2015.

27 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire.

28 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 24–25.

29 Tim Kane, Global U.S. Troop Deployment, 1950–2003 (Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation, 27 October 2004); Donn A. Starry, Press On! Selected Works of General Donn A. Starry, ed. Lewis Sorley (Fort Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army CAC, 2009), 25.

30 Luttwak, Strategy, 230.

31 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 16.

32 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 27.

33 Barbara A. Leaf and Dana Stroul, “The F-35 Triangle: America, Israel, the United Arab Emirates,” War on the Rocks, 15 September 2020.

34 Garrett Martin and Balazs Martonoffy, “Abandon the 2 Percent Obsession: A New Rating for Pulling Your Weight in NATO,” War on the Rocks, 19 May 2017.

35 “NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence: About Us,” 30 November 2020; Monica M. Ruiz, “Is Estonia’s Approach to Cyber Defense Feasible in the United States?” War on the Rocks, 9 January 2018.

36 Luttwak, Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, 198.