Individualism versus Collectivism: Civil Affairs and the Clash of National Strategic Cultures

Individualism versus Collectivism: Civil Affairs and the Clash of National Strategic Cultures

This paper is part of the Civil Affairs Issue Papers, Volume 8: Building a Global Civil-Military Network

If individualism represents the accepted ideology in most Western countries today, then governments as well as militaries should embrace it by investing in such individualist motivations.

Gabriel Ben-Dor1

Introduction

In the world of strategic affairs, culture matters immensely.2 Strategic culture is a model often used in strategic studies to explain how culture affects the behaviors and decisions that leaders and states make. Strategic culture can therefore be an important analytical tool to help us better understand both international relations and the motivations behind a state’s actions.3 While great-power competition has arguably always been present, its recent reemergence has brought a new interest in strategic culture. Nations and their leaders drive strategic affairs, but societies are the true representatives of culture. At the root of the differences between cultures is a fundamental issue in human societies: the role of the individual versus the role of the group.4 If one accepts that societies either fall into individualist or collectivist categories and that these in turn drive a particular strategic cultural profile, then strategic leaders could leverage the strengths and opportunities of their particular societal orientation.

Civil affairs’ (CA’s) ability to build extended civil-military networks may be the answer to providing a global framework for how U.S. strategic culture can best be optimized. This network will ideally leverage some sort of strategic asymmetry nested in the differences between individualism and collectivism in order to gain positional advantage over near-peer threats.5

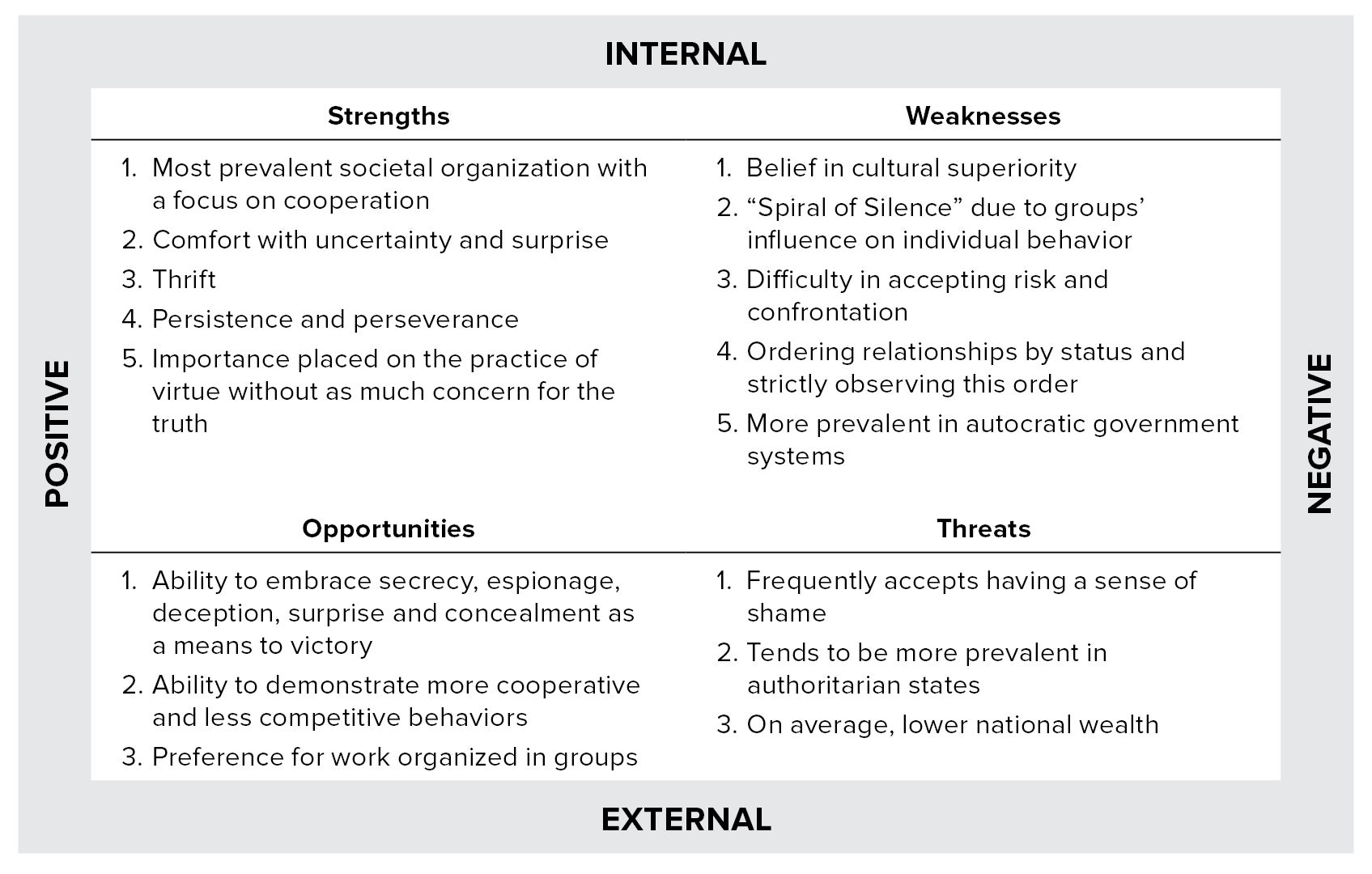

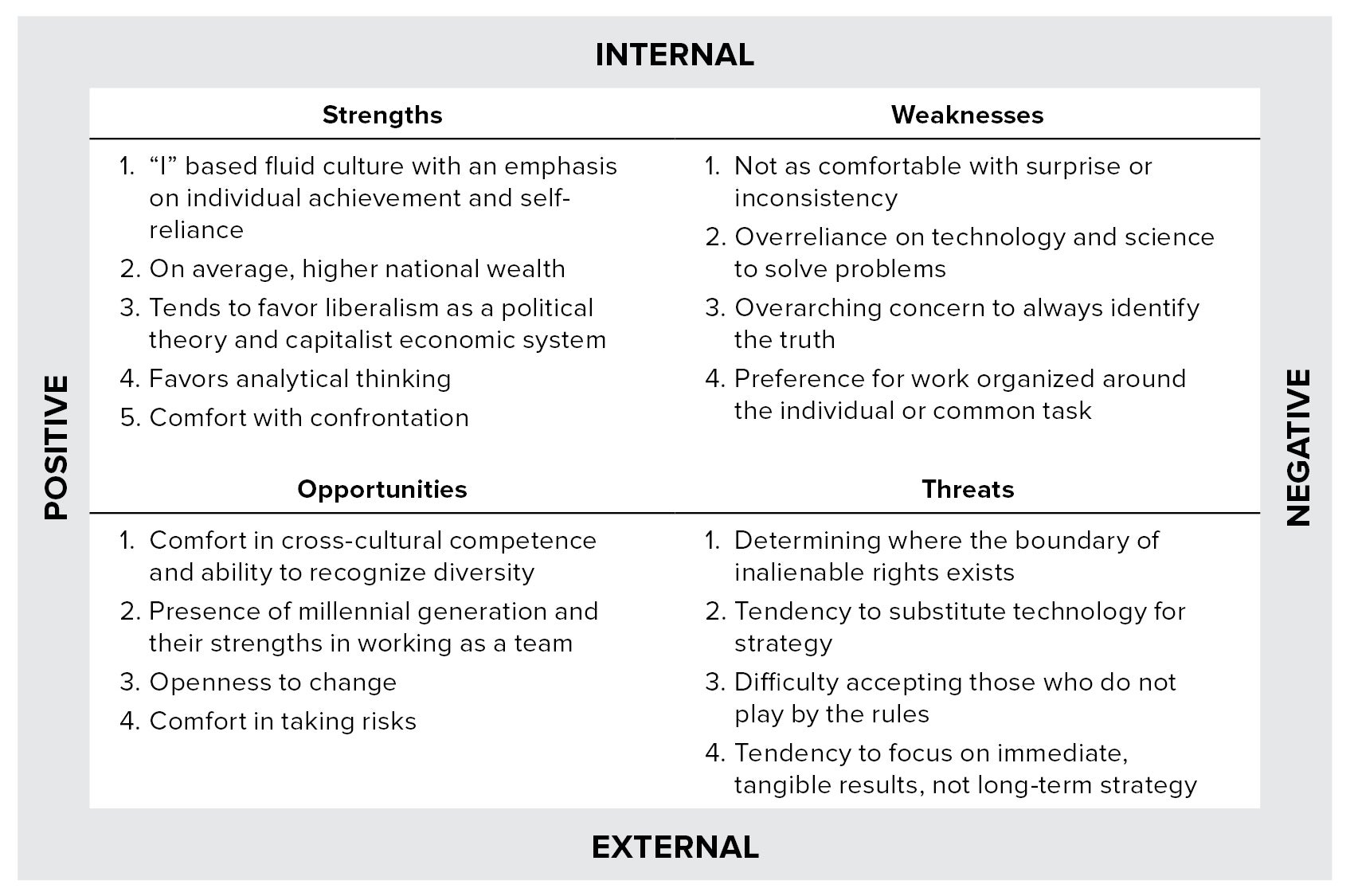

We can see the necessity to optimize a national security strategic culture model rooted in U.S. individualism while also accounting for the collectivism differences of our near-peer competitors. We can do this by examining the significant differences between individualism and collectivism in identifying their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT). We can then propose three doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities and policy (DOTMLPF-P) recommendations for how U.S. strategic and CA leaders can create a global civil-military network leveraging our nation’s cultural strengths.

Overview of Strategic Culture

A standard definition of strategic culture has proven elusive.6 The term, in a modern sense, was coined by Jack Snyder, who in 1977 brought the political cultural argument into modern securities studies as a theory for interpreting Soviet nuclear strategy.7 Central to strategic culture theory is the argument that decisionmaking is not an abstract concept but rather is highly intertwined in the collective values, ideas, beliefs and biases of a nation’s elites and civil society.8 However, with the end of the Cold War and the lack of a clear peer competitor for the United States, strategic culture as a concept began to fall out of favor.

We need to look to sociology for two key terms in this analysis of U.S. strategic culture profile: individualism and collectivism. Put simply, individualism is used to describe those who are more independent, while collectivism often refers to people who are more receptive to group influence or culture. In order to identify where we can gain positional advantage against a competitor, we need to first identify a good individualism versus collectivism measurement and assessment tool.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension Assessment Tools

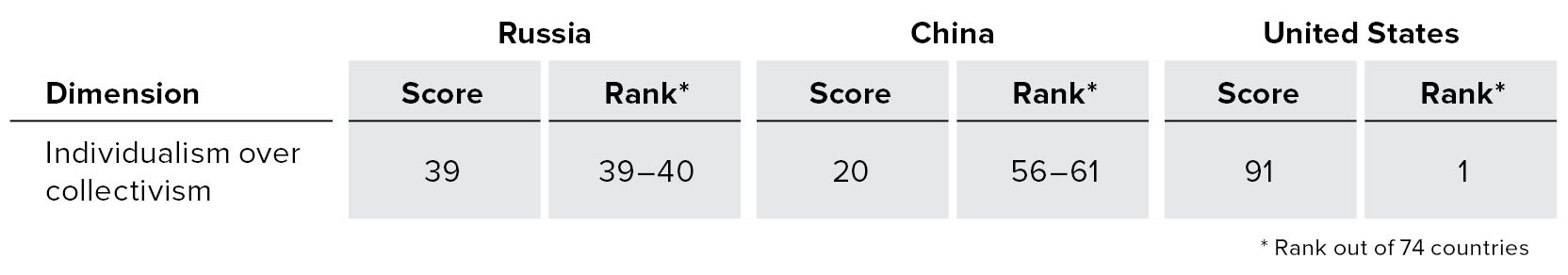

In the 1980s, Geert Hofstede’s pioneering work helped develop a cultural difference construct and assessment measuring tool to explain how Asia’s economy outperformed the economy of the United States and Europe, based on stark differences in four dimensions: power and distance; uncertainty and avoidance; individualism and collectivism; and masculinity and femininity.9 Hofstede’s research helped to develop one of the earliest and most popular frameworks for measuring cultural dimensions in a global perspective. What he found were key differences among 74 different cultures.10 Of interest for this analysis, the United States scored vastly differently from two of our current great-power competitors, China and Russia, in individualism over collectivism. Figure 1 demonstrates this.

Figure 1: Russia-China-U.S. Result Comparison of Hofstede's Dimensions11

What is most important about Hofstede’s work is that he showed that cultural differences can be measured indirectly through asking well-designed assessment questions about people’s values and beliefs. This means that the results can then be interpreted to tell us something about a society and, potentially, about the positional advantages or disadvantages of its strategic culture. Hofstede’s work inspired thousands of empirical studies to further test his construct of cultural value dimensions. Significant meta-analysis reviews have also been done with these supporting studies that continue to show that his work adds value to cross-cultural, organizational behavior and psychology literature.12 These and other extensive peer-reviewed studies helped to further validate his methods of assessment.

Overview of Collectivism

The vast majority of people in our world live in societies where the interests of the group prevail over the interests of individuals.13 These are commonly known as collectivist cultures, which can be seen as “we” based, frequently focused on placing the group’s goals ahead of personal goals and where success is measured by group achievement. Societies in collectivist cultures are integrated into strong cohesive groups, often with their extended families, tribes, etc., and they continue to protect one another in exchange for unquestioned loyalty.14 In experimental situations, collectivists have demonstrated more cooperative and less competitive behaviors than individualists.15 This collective agency has a deep-rooted tradition in which the obligations of individuals are to the larger society and help guide the ethical conduct of the collective.16 Collectivist cultures also create sharper distinctions between groups centered around shared values—and the people outside those groups who do not share those values.17 People in the group(s) will be less accepting of risk but more likely to be comfortable with surprise.18 Finally, collectivists tend to be less comfortable with direct confrontations than individualists.19 Collectivist cultures have been overwhelmingly more representative in societies throughout history.

Overview of Individualism

In an individualist society, the ties among individuals are loose. Its members are expected to look after themselves and possibly their immediate families. People can move around as individuals, and incentives are provided for individuals.20 Individualism in a cultural sense can be seen as an “I” based culture that is full of frequently fluid environments, with an emphasis on individual achievement and self-reliance, and where success is measured by individual achievement. There is an emphasis on autonomy, independence, individual initiative, the right to privacy and the pursuit of happiness and financial security.21

At the core of individualism is also the idea that others are deserving of as much recognition and respect as oneself since there is an inherent equality of all individuals beneath the surface that makes every person equally worthy.22 Individualism in modern society frequently brings with it a capitalist economic system that champions the free market, commercialization, competition, personal consumption and values that centralize individuals having their personal needs and desires met by consumerism.23 Modern Western individualist capitalist civilization is dominated by personal agency.24 Western societies tend to celebrate and reward risk-taking but are less likely to be comfortable with surprise.25

How Individualist and Collectivist Cultures View Each Other

In the eyes of our strategic rivals Russia and China, U.S. strategic culture is characterized as warlike, offensive-minded, expansionist, maritime and materialistic.26 They frequently see U.S. strategic culture and American life as culturally dependent on advanced technology.27 Interestingly, the Chinese in particular have their own definition for individual liberty that is often seen simply as harmony.28 Further, the Chinese language does not have an equivalent word for the term personality, which is often championed as how we define ourselves as individuals in the West.29

Western individualist society has very different views from collective societies on social decisionmaking, independent versus interdependent self-concepts, analytic versus holistic reasoning, and moral reasoning.30 In the camp of individualism, we are often the most extreme representation. Due to the success of its society, Americans have developed an innate belief in the superiority of their sociopolitical and economic ideas.31 American respect for the due process of law, adherence to the law of armed conflict and a desire to minimize collateral damage in warfare go along with an individualist propensity to want to play by the rules so everybody gets a fair shot.32 We therefore often see those who fail to respect international norms as contrary to American values and individualism. Most Americans are less likely to openly criticize other cultures and would likely see collectivist societies more with a sense of ambivalence or apathy.

Use of the SWOT Model to Examine Individualism and Collectivism

A SWOT analysis is a strategic balance sheet for an organization.33 It can be a simple and helpful tool to identify optimization points in order to gain positional advantage over a rival. Likely developed by Albert Humphrey in the 1960s and 1970s through the Stanford Research Institute, it has been used to gather data from Fortune 500 companies for decades and is a well-respected and tested measurement tool.34 Ultimately, the SWOT analysis tool provides an easy way to compare and contrast both collectivism and individualism in order to identify what strategic cultural advantages the United States may have.

Figure 2: Collectivism SWOT Analysis

Figure 3: Individualism SWOT Analysis

Why CA Matters in the Discussion of Individualism versus Collectivism

As noted initially, in the world of strategic affairs, culture matters immensely.35 The importance of culture and strategic-level engagement in CA operations is also significant. “Culture” appears 17 times while “strategic” is mentioned 56 times in Field Manual 3-57, Civil Affairs Operations. It is commonly known that CA forces are expected to be experts in regional and cultural competencies in order to allow them to interact successfully with the variety of cultures present in the local populace and so provide their commander with the best situational understanding of the operational environment (OE). “Greater situational understanding of culture and civil considerations also identifies the risks to U.S. forces and the overall military campaign in the civil component of the OE, thereby ensuring the commander is able to make more timely and informed decisions.”36

We have seen that since we can effectively measure individualism versus collectivism and identify the strengths of the U.S. strategic cultural profile, steps need to be taken now to gain a positional advantage on our collectivist rivals. CA is the optimal partner to leverage the strengths of the U.S. individualist cultural profile via its extended civil-military networks. CA knowledge of civil component factors and how they can impact strategic decisionmaking particularly makes them important in the clash of national strategic cultures.

Recommendations for How U.S. Strategic and CA Leaders Can Leverage Individualism

Based on the SWOT analysis, there are three key DOTMLPF-P recommendations we can make for how strategic planners and CA leaders can better optimize individualism as a component of U.S. strategic culture.

Leadership and Education: Institutionalize Cross-Cultural Competence to Counter Russian and Chinese Collectivism

The SWOT analysis clearly shows that a strength of individualism is that it generally creates an environment, often with its own challenges, that encourages cross-cultural appreciation and recognizing diversity. “The need for cross-cultural competence has only increased as the strategic environment becomes more complex.”37 Steps should be taken to ensure that strategic planners and CA leaders can become more psychologically astute by educating themselves in the realm of psychologists, cultural psychologists and anthropologists.38 This also means education in identifying the key differences between individualism versus collectivism. Institutions that train strategic leaders, such as the service colleges, should expand lessons on how culture and cognitions impact the decisionmaking process.39 This cross-cultural competence should not only be instructed to strategic leaders but also be present in institutional instruction at the operational and tactical levels of war. It therefore may need to be presented throughout professional military education and not just at its most senior level.

Personnel: Prioritize U.S. Individualist Values as a Component of Our Strategic Culture

Strategic Army and CA leaders must be willing to prioritize individualist values as a component of strategic culture. We can start by making our Army look more like the individualist U.S. society that makes up its ranks. This is particularly important given the large population of millennials that makes up the largest age cohort in the military. Millennials are seen generally as anyone born between 1981 and 1996 and are today between the ages of 26 and 41. The 2020 U.S. DoD demographics profile highlighted that approximately 47.4 percent of the total DoD military force is between the ages of 26 and 40—squarely in the millennial generation.40 This cohort also currently makes up the vast majority of mid- to lower senior grade officers and NCOs. The individualism SWOT analysis shows the opportunity that flag officers and senior noncommissioned advisor leaders have to leverage the noncompetitive teamwork mindset of millennials and take time to explain the “why” in order to maximize their capability. By appealing to the individualism strengths of millennials, this group will better understand the tasks at hand and strengthen their resolve to complete it.41

Training: Leverage Clear U.S. Positional Advantages in Individualism over Collectivism

In order to address a weakness noted in the SWOT analysis, U.S. strategic leaders should learn to be more accepting of uncertainty and take advantage of it, much like the Chinese do.42 As noted, China’s and Russia’s strategic cultures are predicated on a preference for winning without fighting and for leveraging deception, ambiguity and secretiveness.43 The United States may need to become more comfortable reassessing the importance it places on moral values, truth and playing by the rules. Training on scenarios at all levels of war that are contrary to American individualist values is difficult to embrace as we are not often comfortable with surprise or inconsistency. However, failure to expose our leaders to morally ambiguous surprises in training scenarios could potentially create strategic vulnerabilities or military risks.44 Thanks to individualism’s appreciation and openness to change—along with a general comfort in taking risks—the United States has positional advantage over collectivist cultures and can be more accepting of these moments of surprise, as long as we can first train for them.

Areas for Further Investigation

While we have looked exclusively at Russian and Chinese collectivism to contrast U.S. individualism in this analysis, can we extend the recommendations noted to address other great-power rivals in the contemporary security environment? When we look at the “4+1” strategic threat framework, we could likely also see North Korea, Iran and violent extremist organizations more favorably embracing collectivism. There are some common collectivist characteristics that have been associated with all of our rivals’ strategic cultures, to include dreams of past glory, a history of humiliation, self-reliance and authoritarian popular control, among others.45 However, further research would be needed to see if the SWOT analysis of one collectivist culture could simply be applied to others.

Additionally, as China in particular continues to become a wealthier country, and its citizens continue to grow in wealth, what effect will this have on the potential rise of individualist characteristics in Chinese society? More importantly, what effect will these individualist Western values potentially have on modern Chinese strategic culture? Further analysis needs to be done on how the United States can maintain long-term positional advantage; Hofstede’s work has shown that countries become more individualist after they increase their wealth.46

Conclusion

In the renewed age of great-power competition, we have seen that there is a significant clash of strategic cultures. We have examined the drivers of strategic culture and highlighted the characteristics of Chinese and Russian collectivism and U.S. individualism. We have conducted a SWOT analysis and proposed three DOTMLPF-P recommendations for a contemporary national security model that optimizes individualism as a key component of U.S. strategic culture.

CA’s ability to build extended global civil-military networks is much of the answer to providing a global framework for how U.S. strategic culture based in individualism can best be optimized. CA leaders are economy-of-force advisors to the commander in how the cultural dimension impacts the strategic and operational environments and what the best military responses should be. We can help senior strategic leaders win in the world of strategic competition by making sure they can better understand the differences between individualism and collectivism. “Winning in competition is critical for the strategic interests of the U.S. government because it reduces the requirement to deploy and utilize combat forces.”47

Without a clear recognition and understanding of this strategic cultural divide, primarily shown in the differences between individualist and collectivist societies, the United States runs the risk of undermining its strategic agenda, including its most important positional advantage in great-power competition.48 While culture is a key factor in contemporary international security, further research still needs to be done on the depth and scope of this influence.49 Fortunately, the United States has the capacities and capabilities in multiple whole-of-nation aspects that strategic Army planners and CA leaders can leverage now to optimize a new national strategic culture model rooted in individualism.

★ ★ ★ ★

Colonel Marco A. Bongioanni serves as a U.S. Army Reserve Civil Affairs officer and has held a variety of command and staff assignments. He is a graduate of the U.S. Army War College and a New York State Licensed Mental Health Counselor in his civilian career, working for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His professional interests include human behavior and applied psychology. The views expressed in this paper are his alone and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Army or of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Gabriel Ben-Dor et al., “I Versus We,” Armed Forces & Society 34, no. 4 (July 2008): 586.

- Brice F. Harris, America, Technology and Strategic Culture (New York: Routledge, 2009), 152.

- Ume Farwa, “Belt and Road Initiative and China’s Strategic Culture,” Strategic Studies 38, no. 3 (2018): 45.

- Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede and Michael Minkov, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2010), 74.

- Steven Metz and Douglas V. Johnson II, Asymmetry and U.S. Military Strategy: Definition, Background, and Strategic Concepts (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2001), 1.

- Russell D. Howard, Strategic Culture (MacDill Air Force Base, FL: Joint Special Operations University JSOU Report 13-8, December 2013), 1.

- Jeffrey S. Lantis, “Strategic Culture: From Clausewitz to Constructivism,” Strategic Insights 4, no. 10 (October 2005): 6–7.

- Farwa, “Belt and Road Initiative and China’s Strategic Culture,” 43.

- Geert Hofstede and Michael Harris Bond, “The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth,” Organizational Dynamics 16, no. 4 (Spring 1988): 5.

- Hofstede and Bond, “The Confucius Connection,” 16.

- Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations, 169.

- Vas Taras, Bradley L. Kirkman and Piers Steel, “Examining the Impact of Culture’s Consequences: A Three-Decade, Multi-Level, Meta-Analytic Review of Hofstede’s Cultural Value Dimensions,” Journal of Applied Psychology 95, no. 3 (2010): 431.

- Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations, 74.

- Hofstede and Bond, “The Confucius Connection,” 11.

- Anne Lise Bjonstad and Pal Ulleberg, “Is Established Knowledge About Cross-Cultural Differences in Individualism-Collectivism Not Applicable to the Military? A Multi-Method Study of Cross-Cultural Differences in Behavior,” Military Psychology 29, no. 6 (2017): 479.

- Christopher Stone, “The Implications of Chinese Strategic Culture and Counter-Intervention Upon Department of Defense Space Deterrence Operations,” Comparative Strategy 35, no. 5 (2016): 335.

- Thomas Sole, The Spiral of Silence in the U.S. Army, Strategy Research Project (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, April 2017), 16.

- Thomas G. Mahnken, Secrecy and Stratagem: Understanding Chinese Strategic Culture (Double Bay, NSW: Lowy Institute for International Policy, February 2011), 26.

- Bjonstad and Ulleberg, “Established Knowledge About Cross-Cultural Differences,” 485.

- Hofstede and Bond, “The Confucius Connection,” 11.

- Ben-Dor et al., “I Versus We,” 586.

- Eloise Forgette Malone and Chie Matsuzawa Paik, “Value Priorities of Japanese and American Service Academy Students,” Armed Forces & Society 33, no. 2 (January 2007): 179.

- Ben-Dor et al., “I Versus We,” 568.

- Mahnken, Secrecy and Stratagem, 5.

- Mahnken, Secrecy and Stratagem, 26.

- Andrew Scobell, “China’s Real Strategic Culture: A Great Wall of the Imagination,” Contemporary Security Policy 35, no. 2 (2014): 218–19.

- Brice F. Harris, “United States Strategic Culture and Asia-Pacific Security,” Contemporary Security Policy 35, no. 2 (2014): 294.

- Stone, “The Implications of Chinese Strategic Culture,” 335.

- Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations, 93.

- Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan, “The Weirdest People in the World?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33, no. 2–3 (2010): 9.

- Harris, “United States Strategic Culture and Asia-Pacific Security,” 294.

- Metz and Johnson, Asymmetry and U.S. Military Strategy, 12.

- Ifediora Christian Osita, Idoko Onyebuchi R. and Nzekwe Justina, “Organization’s Stability and Productivity: The Role of SWOT Analysis an Acronym for Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Threat,” International Journal of Innovative and Applied Research 2, no. 9 (2014): 24.

- Osita, Onyebuchi and Justina, “Organization’s Stability and Productivity,” 27.

- Harris, America, Technology and Strategic Culture, 152.

- Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 3-57, Civil Affairs Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, July 2021), 4–21.

- Sean N. Fisher, The Decisive Leadership Advantage: Mission Command in a Multinational Environment, Strategy Research Project (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, April 2016), 13.

- Metz and Johnson, Asymmetry and U.S. Military Strategy, 22.

- Mark N. Brown, The Impact of Strategic Culture and Cognition on U.S. Outcomes, Strategy Research Project (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, March 2010), 14.

- DoD, Demographics Profile of the Military Community 2020 (Washington, DC: U.S. DoD, 2020), 8.

- Jason Halloren, The Character and Motivation of Millennials: Understanding Tomorrow’s Leaders, Strategy Research Project (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, April 2015), 16–17.

- Stone, “The Implications of Chinese Strategic Culture,” 341.

- Howard, Strategic Culture, 24.

- Metz and Johnson, Asymmetry and U.S. Military Strategy, 12.

- Howard, Strategic Culture, 65–71.

- Hofstede and Hofstede, Cultures and Organizations, 353.

- FM 3-57, 3–20.

- Harris, “United States Strategic Culture and Asia-Pacific Security,” 302.

- Lantis, “Strategic Culture,” 31.

Continue reading Civil Affairs Issue Papers, Volume 8:

Foreword

by Colonel Joseph P. Kirlin III, USA, Ret.2021 Civil Affairs Symposium Report

by Colonel Christopher Holshek, USA, Ret.Civil Affairs and Great-Power Competition: Civil-Military Networking in the Gray Zone

by Sergeant First Class Nicholas Kempenich, Jr., USAInnovation as a Weapon System: Cultivating Global Entrepreneur and Venture Capitalist Partnerships

by Major Giancarlo Newsome, USA, Colonel Bradford Hughes, USA, & Lieutenant Colonel Tyson Voelkel, USAMaximum Support, Flexible Footprint: Civilian Applied Research Laboratories to Support the 38G Program

by Dr. Hayden Bassett & Lieutenant Kate Harrell, USNRIndividualism versus Collectivism: Civil Affairs and the Clash of National Strategic Cultures

by Colonel Marco A. Bongioanni, USABack to Basics: Civil Affairs in a Global Civil-Military Network

by Major Jim Munene, USA, & Staff Sergeant Courtney Mulhern, USA