Back to Basics: Civil Affairs in a Global Civil-Military Network

Back to Basics: Civil Affairs in a Global Civil-Military Network

This paper is part of the Civil Affairs Issue Papers, Volume 8: Building a Global Civil-Military Network

Introduction

The Civil Affairs Corps has a unique opportunity to shape its future and that of the U.S. Army. Civil affairs (CA) should proceed deliberately and expediently while gaining an understanding of what strategic competition truly is, employing the most current and available tools accordingly and demonstrating how CA can participate in a global civil-military network. By acknowledging and understanding what motivates U.S. competition and competition from its adversaries and allies, the United States can leverage strategic global networking and remain on top as a world leader.

Throughout the years, the United States has worked hard to ensure strategic and stable relationships in order to defend democratic values and the American way of life. As stated in the 2018 National Defense Strategy, “Our network of alliances and partnerships remain the backbone of global security.”1 While relationships and networks have helped the United States successfully in years past, maintaining them must be continual and purposeful; this must be an ongoing priority. President Biden’s 2021 Interim National Security Strategy (NSS) Guidance states that the United States must lead with democracy and “revitalize America’s unmatched network of alliances and partnerships.”2

It is clear that the United States values its networks and partnerships throughout the world. Their retention does not come without many challenges, but CA Soldiers are capable and eager to play their part in advancing U.S. objectives. It has been well articulated that “as a diverse and people-centric force for influence, relationship building and competition, CA is an ideal force to demonstrate U.S. involvement and interest to contest adversarial powers and actors globally.”3

Maintaining a global civil-military network is fundamental to increasing the U.S. military capabilities in the 21st century. CA functions and core competencies support the importance of relationships and networking and must continue to be prioritized. To do this, paradoxically, the CA Corps must go back to the basics of CA operations (CAO) for the United States to maintain its global power in access and influence, especially in the gray zone.

Geographical Focus

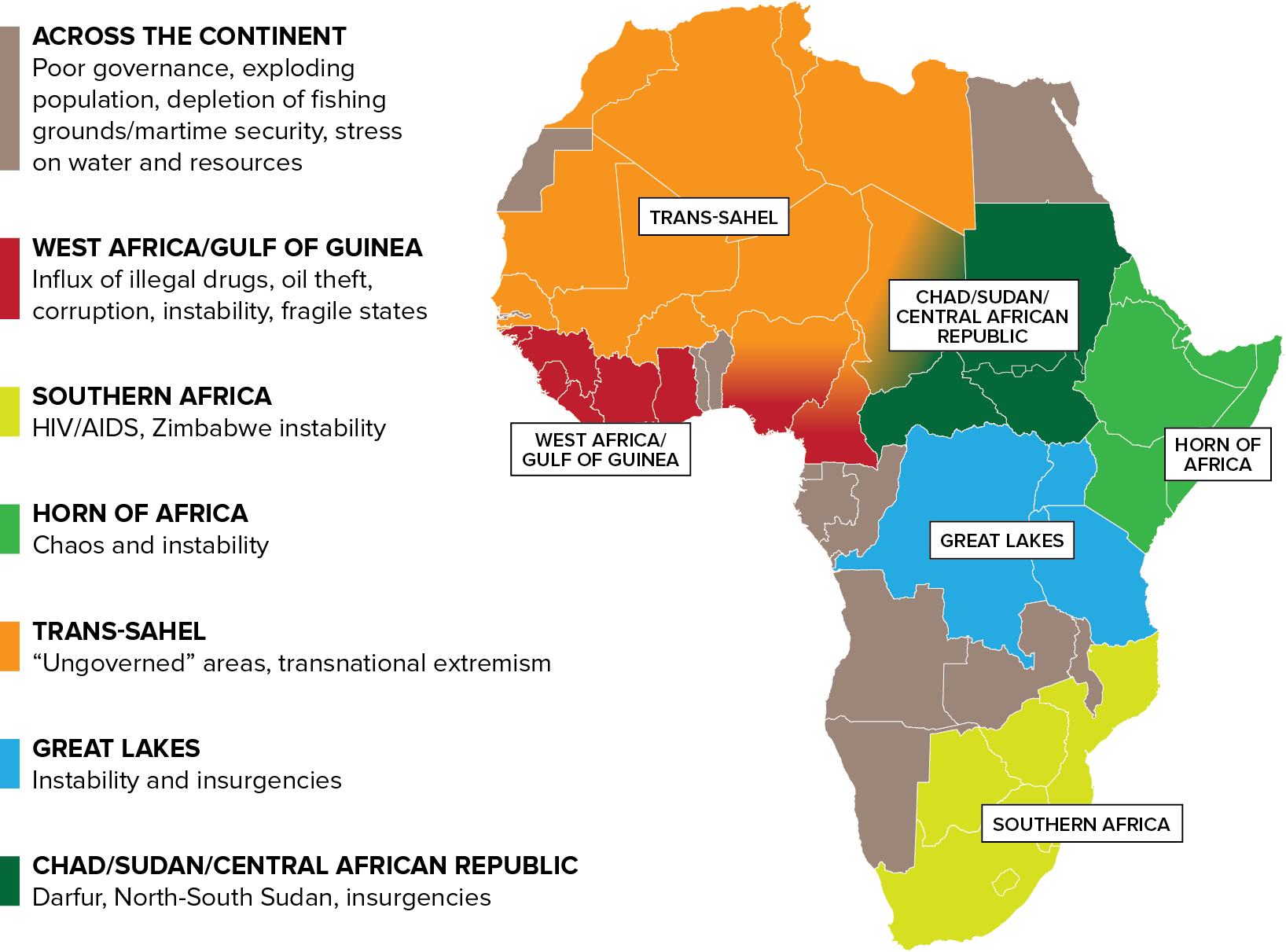

Focusing on the U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) region, building a global civil-military network is of utmost importance in a continent facing many of its own challenges. In Africa as a whole, China is the United States’ biggest competitor in economics, politics and security. China has made abundantly clear its presence and strategic objectives across the continent of Africa. It is arguable that China is taking advantage of an unstable continent plagued with challenges to foster its own agenda in the region. The NSS suggests, “In many areas China’s leaders seek unfair advantages, behave aggressively, and coercively, and undermine the rules and values at the heart of an open and stable international system.”4 With a strong global civil-military network, the United States can defeat China as the main competition in the USAFRICOM region.

Figure 1. Africa: A Continent of Challenges5

China as the Biggest Great-Power Competitor in Africa

In order for there to be any type of competition, competitors need to understand their competition. According to American diplomat and former ambassador in Africa Davin H. Shinn, there are several things that motivate China’s reach for influence in Africa. Access to raw materials, increasing exports to Africa and receiving international political support are China’s main interests.6 Coupled with China’s economic power, this makes China the biggest competitor with the United States in Africa because of their adversarial interests as great interventionist powers.

China’s strategy of building its own global civil-military network in the USAFRICOM region is in heavily investing its finances, as evidenced by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In Ethiopia, for example, Chinese finance provides critical support for the Ethiopian government’s legitimacy as electricity, transport and employment opportunities continue to expand, stimulating economic growth and helping promote exports to other countries. As a result, China is using its financial resources in technology, personnel and investments to influence the policies of the host nations (HNs).

China claims that its strategy does not intend to create “debt traps” but rather to build infrastructure and spark economic development in other countries as a win-win for them both. Whether or not this is true, the United States must consider if this strategy is realistic. In addition, China is not exactly known for either its transparency or being held accountable for its actions.

In building a global civil-military network, the United States should hold firm on its strategy for regional security, stability and peace, but it should not throw its financial might around to compete directly with China in funding projects in the USAFRICOM region. Analysts say that Ethiopia’s firebrand prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, is positioning the country to leverage competition between the West and China to attract even greater investment and reduce the country’s dependence on Beijing. With an unwavering strategy of regional security, stability and peace in the region, a U.S.-led, global, civil-military network would succeed. CA must recognize its role as such in competition in Africa and offensively participate because, as 2021 CA Roundtable keynote speaker Lieutenant General Eric J. Wesley, USA, Ret., stated, “You can’t compete if you’re not there.”7

Strategy and Concept of Operations

Maintaining Sustainable Relationships

The core of building a global civil-military network begins with building and maintaining strong relationships between partners and working groups. According to Lieutenant General Charles Hooper, USA, Ret., relationships with partners built in an HN “must be persistent, not episodic.” Hooper emphasized, “We’re not building nations anymore, we’re building networks.” This concept is compulsory “to build the strategic, operational, and human capital necessary for competition even more than conflict.”8

CAO in an HN should therefore involve an array of extracurricular activities with an intention of team building and cohesion by means of civil engagement (CE) and civil reconnaissance (CR). For example, in the Horn of Africa in Djibouti, deployed military personnel can take advantage of a game of soccer with the local nationals to gather information about the operational environment while staying in and maintaining the established lines of effort.

This simple extracurricular activity with the locals can create an atmosphere of trust on the soccer field that can translate to a great working relationship while conducting CAO. Once a strong relationship with the locals is built, other stakeholders and partners in the HN can be invited to participate. For example, during numerous deployments of CA teams to the Horn of Africa in 2020–2021 (some of which included the authors), American embassy personnel in Djibouti were invited and gladly joined the soccer games and other extra- curricular activities run by the CA teams. What started as a mere series of soccer games slowly transitioned into an informal CAO working group because of the ongoing relationship built over time. This is a small, tactical demonstration of how forces like CA can be a multiplier to other agencies to expand America’s soft power and the positional advantages of access and influence at the heart of strategic competition. If more CA forces were deployed for such forward CR and CE missions, as strategic sensors, the strategic and operational values-added to both commanders statespersons could be more decisive than helpful.

Worth noting is the art of building relationships through partnerships, coalitions and alliances. This entails CAO and military liaisons working together with security force assistance brigades (SFABs), National Guard state partners, security cooperation initiatives, embassies, foreign area officers (FAOs), the Organization of African Unity (OAU), African Mission Somalia (AMISOM), the Peace Corps, commercial enterprises, humanitarian groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Both China and the United States have interests in maintaining influence with the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU). Currently, Africa has 54 countries in the UN, amounting to more than one-quarter of all UN members. According to the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations for 2020–2021, the United States is the top provider, at 27.89 percent of assessed contributions, with China following at 15.21 percent. However, China has deployed more peacekeepers to Africa missions than any other UN Security Council permanent member.9

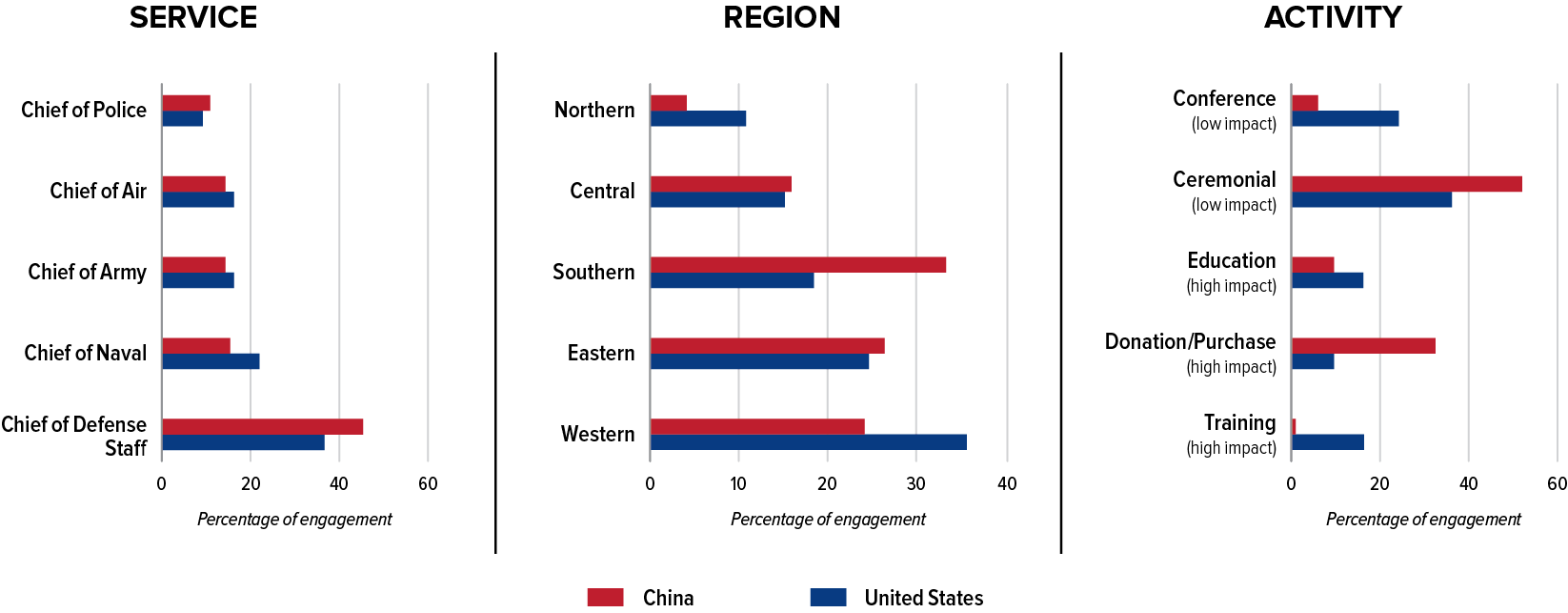

A study published in August 2021 conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) measured Chinese and U.S. engagements with African security chiefs. The study showed that “China has engaged less than 19% of current and former African security chiefs, while the United States has engaged almost 43%.”10 This translates to China engaging with top African security chiefs at less than half the rate of the United States. This also translates as a limit to Chinese relationship-building and an advantage for the United States and CA to maintain.

Figure 2. Chinese and U.S. Engagements in Africa11

As it pertains to Chinese relations within Africa, there are strains in the relationships created by hefty loans related to infrastructure projects. Countries such as Djibouti, Kenya and Uganda have massive debts owed to China due to road and railway development. This could lead to conflict over the loan terms, defaulting on loans and, most of all, strained relations. The Center for African Studies states that China is learning to be more disciplined with loan terms and agreements, such as in Kenya, where loan terms changed to include their Indian Ocean port of Mombasa as collateral for the loan the government secured from China’s Exim Bank to build the Mombasa–Nairobi railway.12

The facts and numbers remain: Africa is indebted to China as a part of its global strategy. Shinn argues that an increase in economic dependency leads to an increase in security and political dependency.13 The increase in strained relations due to China’s global-networking strategy in Africa provides the United States an opportunity to increase CA engagements, leading to a larger U.S. presence and to the United States being Africa’s preferred partner.

The Impact of Social Media in the Global Network

When it comes to global networking, technology and social media are the key components and will continue to be as the world advances. In 2021, it was estimated that out of the 7.7 billion people in the world, 3.96 billion people are currently using some form of social media. Furthermore, 58.11 percent of the world’s population above the age of 13 is active on social media. In the United States alone, 90 percent of Generation Z (ages 18–29) have at least one social media account.14

In 2020, Facebook was the leading social network with 2.7 billion users worldwide. YouTube and WhatsApp followed with 2 billion, then Messenger, WeChat and Instagram, all having 1 billion or more users. By 2021, newcomer TikTok had joined the 1 billion user club.15 These numbers are only increasing, and this means that the current and upcoming generation of military members use social media as part of their everyday lives and as a part of their military service. These statistics indicate how important virtual relationships and connections are to people around the world. The military needs to capitalize on this method of networking to develop and maintain relationships around the world.

In a real-world CAO example, when missions were canceled and Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti was shut down in 2020 due to COVID-19, social media was the only link between maintaining relationships already formed and continuing the mission. CA teams (CATs) had to adjust fire to the mission and, as the world did, adapt to the new virtual normal. Communicating through WhatsApp became the method by which CAO maintains presence and influence. You cannot compete if you are not actively participating in the present place and time. It should be noted that some relationships perished because of not being able to connect in person. It can be hard to recover those relationships once momentum has been lost and new CATs cycle through different missions.

Regarding competition with China as it relates to social media, there really is no level competition. China strictly monitors social media sites within its borders, and the United States should use this to its advantage. China does not allow Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube or Instagram,16 all sites that could be useful in aiding in influence on the global scale. Google and its related sites are not available without a virtual private network (VPN), and instead China uses its own search engine, Baidu, to censor and monitor searched information. Chinese-owned TikTok, developed by ByteDance,17 is not even allowed for its citizens. Rather they use their own, Douyin, and neither app can be accessed by the other. These Chinese limitations to free and open networking provide a huge advantage for the U.S. military in terms of competition; this needs to be capitalized on before China decides to join the world in social networking.

Social media as it relates to global networking does not come without its own set of challenges. One never fully knows who they are connecting with on the other side of a screen or who could potentially be seeing the correspondence. Other risks include the matter of operational security (OPSEC), the potential for unprofessional behavior and communication lost in translation that could be detrimental to the relationship. In addition, there is also the issue of the overlap between psychological operations (PSYOP) and the public affairs office (PAO). The PSYOP mission could be to get certain themes and messages out, and that could duplicate efforts with the CA mission. This issue reinforces that both CA and PSYOP need to be working closely together in a partnership. The PAO has its own mission set and various social media sites it uses. CA would need to differentiate between networking with actual partners on a personal level and getting out messages to the masses for the greater good of the U.S. military. In addition, the CSIS declares that “both Chinese and U.S. government and media coverage have limited reach and influence in Africa,” and that “most U.S. engagements are posted on the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) website, embassy pages, and social media—including the photo-sharing website Flickr—which Africans do not frequently visit.”18 This needs to be considered in the CA strategy when competing for a global network.

Social networking sites allow people to connect 24 hours a day and seven days a week in almost every corner of the world. The global social network already established through sites such as Facebook would be critical in fostering partnerships and allies and for increasing favorability with the U.S. military when compared to its competition. Perhaps each CAT or company in-country could administer a Facebook group, which could be passed on to CATs cycling through. This would aid in greater continuity as well as user-friendliness compared to inconsistent file sharing and various databases. This would also prevent servicemembers from having to use their personal accounts with personally identifiable information (PII), family information and pictures. Social media will not fade away anytime soon, and CA will need to make this a priority in order to stay relevant as a top contender with its competitors.

Security and Stability

Security in any nation is crucial to any sort of stability and progress. Without security, nations can be vulnerable to adversaries taking advantage of the instability, socioeconomic deprivation and general uncertainty. Take, for example, Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti. The U.S. presence alone provides Djibouti enough security from the hostilities from neighboring Somalia, and the instabilities across the Red Sea in the Middle East in Yemen, to have a positive outlook on its economy. Djibouti’s output growth was set to reach 5.5 percent in 2021 and to average 6.2 percent over 2022 and 2023.19 This growth is in part due to its ports but also in part to the nation’s security. With this stability over time, other world players will want to invest, providing Djibouti with autonomy and the ability to move away from dependence on competitors like China. The United States can then empower Djibouti to compete with China in its own arena, and the relationships cultivated over time will be strengthened because of the success of Djibouti as the HN with the United States.

Political instability and security issues have led to some Chinese contracts and projects not going forward and subsequently not being paid. In 2016, 300 Chinese oil workers had to be evacuated in South Sudan due to a shoot-out between rival militias. This has led to an uptick in “private security” agencies going to Africa in large numbers.20 “Private security” is misleading, as the groups are still controlled by China and serve its interests. Weapons restrictions and other cross-cultural differences could lead to unrest between China and Africa, and the United States should also consider this a part of its networking strategy.

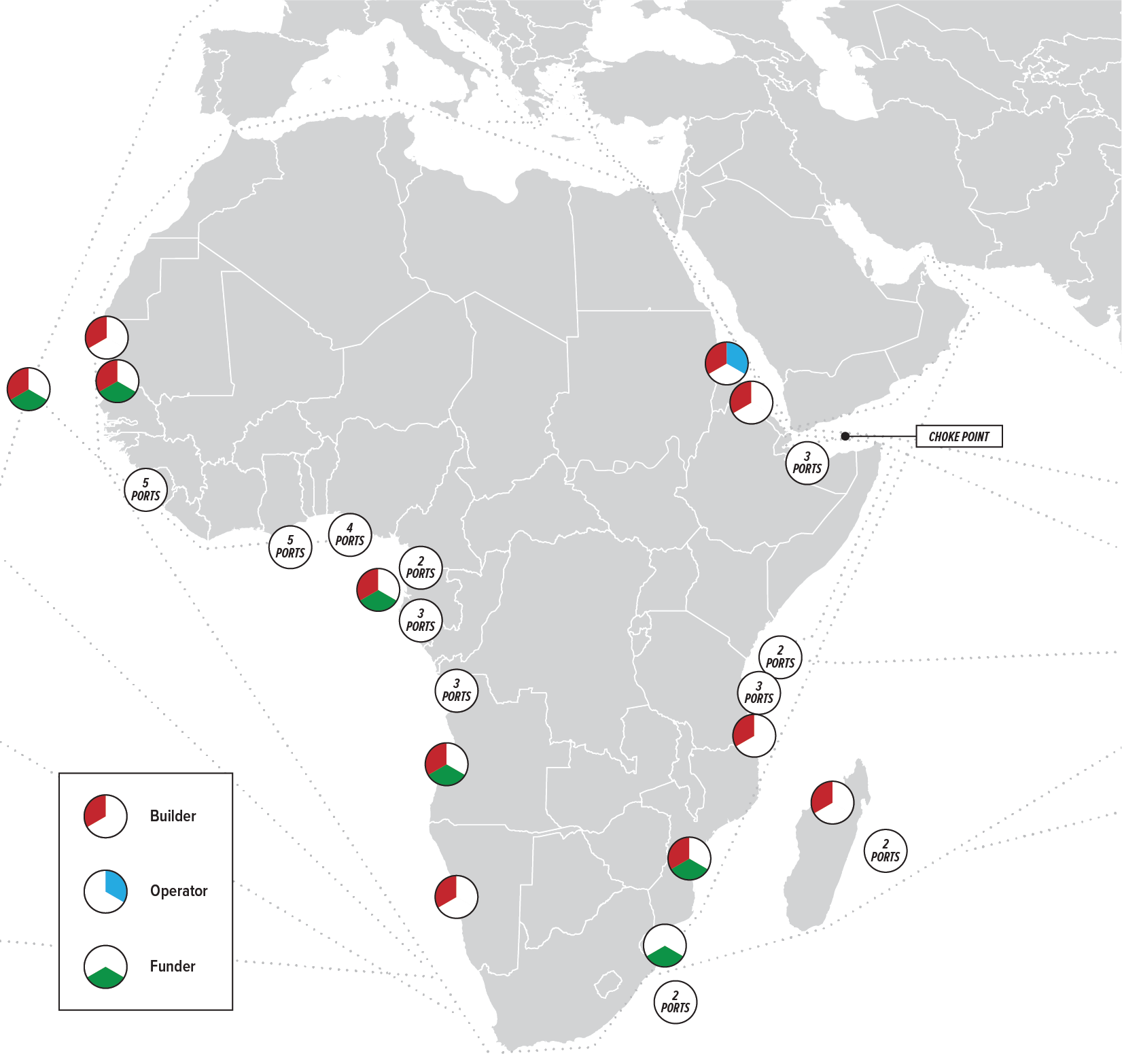

From a global-networking security standpoint, the U.S. military needs to be mindful of the growing port investments in Africa made by China. Figure 3 shows the various port projects that Chinese companies have financed, constructed or operated. There are at least 46 ports across sub-Saharan Africa, all of which have been built according to People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy specifications.21 Figure 3 demonstrates ports along both the west and east coastlines, giving access to both Atlantic and Pacific waters. Additionally, while the United States has its Camp Lemonnier base in Djibouti, China has its only overseas PLA base there as well. It is no coincidence that this geographically significant location has high strategic value for its competitors, and China has made it clear that it intends to be a global military power.

Figure 3. Chinese Port Investments in Africa22

Additionally, tapping into the cyber and satellite arenas while strengthening these two industries should also be a part of the U.S. military strategy as it relates to building a global network. The cyber world has become the new way to conduct business and warfare. Having coalition partners in the HN will boost the United States’ ability to counter cybercrimes when they are conducted in a distant land where the United States does not have law enforcement jurisdiction. As for the satellites, the United States is the leader in GPS technology. Working with coalition partners and HNs, the United States is better positioned to coordinate its GPS capabilities to foster a stronger global civil-military network and to counter and dismantle electronic warfare activities from adversaries.

Conclusion

Building a global civil-military network is fundamental to increasing the United States’ military capabilities and national interests in the 21st century. USAFRICOM, alongside its African and interagency partners, is charged with the responsibility of enhancing security and stability in Africa to advance and protect U.S. national interests, which it has successfully done. It needs to be maintained regardless of the competition.

According to Advocacy Network for Africa (ADNA), based in Washington, DC, a few suggestions to facilitate a stronger global civil-military network would be to “advocate more U.S. support and resources for human rights, conflict resolution, and negotiation in Africa to develop long-term peace based on the often-difficult agreements among different legitimate stakeholders, including the many varieties of Islamic and Islamist organizations across Africa.”23

Countries need to be empowered by U.S. relations to stimulate their own economy and provide infrastructure within their own borders. While China provides capital, the United States puts efforts into building relationships, and what people want are trustworthy partners and healthy working relationships. The offensive solution to competing with China in the Horn of Africa is to build and foster relationships with HNs and allies.

China’s strategy is well thought out and calculated. It will do what it takes to be a global superpower, and it is obvious that its infrastructure projects, loans, security postures and “private security” agencies all lead back to keeping its communist party in power. The United States cannot only rely on its past successes and reputation to stay in competition. More than ever, CA needs to have active participation as it relates to global networking, and that should be done by going back to the basics of CAO: being proficient in CA doctrine, sustaining relations, staying relevant in the social media arena and supporting a security stance that benefits the United States’ best interests while empowering the HN.

Building a global civil-military network is a strategic direction that the United States takes. It is nested in the national interests and policy goals of protecting the American way of life, achieving economic prosperity, attaining peace through strength and advancing American influence. The end state goal is for the United States to successfully compete with other world nations over the long term and to preserve global security.

★ ★ ★ ★

Major Jim Munene is the Delta Company Commander at the 492nd Civil Affairs Battalion in Buckeye, Arizona. Originally from Kenya, Munene deployed to the Horn of Africa as a civilian contractor and was able to see challenges faced in Africa as a civilian and as a part of the U.S. Army.

Staff Sergeant Courtney Mulhern is in Delta Company at the 492nd Civil Affairs Battalion in Buckeye, Arizona. Mulhern was deployed to Djibouti, Africa, in 2020 with the 411th CA Battalion and served as a team sergeant. Mulhern faced challenges with COVID-19 shutting down missions but was able to gain an international CA perspective in Africa.

- The White House, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, 2018.

- The White House, Interim National Security Strategy Guidance, 2021.

- Civil Affairs Association, “2021–22 Civil Affairs Call for Issue Papers,” Eunomia Journal, 23 June 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “China’s Interests in Africa—Amb. David Shinn,” YouTube, 16 August 2019.

- Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns, “Africa: Concerns About U.S. Military Policy,” NewsNotes 40, no. 4 (May–June 2015).

- Simon Marks, “Ethiopia Plays Europe Off China in Bid to Boost Investment,” Politico, 2021.

- Colonel Christopher Holshek, USA, Ret., 2021 Civil Affairs Roundtable Report—Roundtable Identifies Opportunity for Civil Affairs to Help Shape “Competition” (Fort Bragg, NC: Civil Affairs Association, May 2021), 2.

- Colonel Christopher Holshek, USA, Ret., “2020 Civil Affairs Symposium Report,” in Volume 7, 2020–2021 Civil Affairs Issue Papers: Civil Affairs: A Force for Influence in Competition (Arlington, VA: AUSA, March 2021), 6.

- “How We Are Funded,” United Nations Peacekeeping.

- Judd Devermont, Marielle Harris and Alison Albelda, “Personal Ties: Measuring Chinese and U.S. Engagement with African Security Chiefs,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 4 August 2021.

- Devermont, Harris and Albeda, “Personal Ties.”

- Paul Nantulya, “Implications for Africa from China’s One Belt One Road Strategy,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 22 March 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “China’s Interests in Africa.”

- Brian Dean, “How Many People Use Social Media in 2021?” Backlinko, 10 October 2021.

- Dean, “How Many People Use Social Media.”

- Dean, “How Many People Use Social Media.”

- Salvador Rodriguez, “TikTok Insiders Say Social Media Company Is Tightly Controlled by Chinese Parent Bytedance,” CNBC, 25 June 2021.

- “The List of Blocked Websites in China,” Sapore Di Cina, 8 November 2021.

- “The World Bank in Djibouti,” World Bank, 1 November 2021.

- Paul Nantulya, “Chinese Security Firms Spread Along the African Belt and Road,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 15 June 2021.

- Judd Devermont, “Assessing the Risks of Chinese Investments in Sub-Saharan African Ports,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 4 June 2021.

- Devermont, “Assessing the Risks of Chinese Investments.”

- Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns, “Africa: Concerns About U.S. Military Policy.”

Continue reading Civil Affairs Issue Papers, Volume 8:

Foreword

by Colonel Joseph P. Kirlin III, USA, Ret.2021 Civil Affairs Symposium Report

by Colonel Christopher Holshek, USA, Ret.Civil Affairs and Great-Power Competition: Civil-Military Networking in the Gray Zone

by Sergeant First Class Nicholas Kempenich, Jr., USAInnovation as a Weapon System: Cultivating Global Entrepreneur and Venture Capitalist Partnerships

by Major Giancarlo Newsome, USA, Colonel Bradford Hughes, USA, & Lieutenant Colonel Tyson Voelkel, USAMaximum Support, Flexible Footprint: Civilian Applied Research Laboratories to Support the 38G Program

by Dr. Hayden Bassett & Lieutenant Kate Harrell, USNRIndividualism versus Collectivism: Civil Affairs and the Clash of National Strategic Cultures

by Colonel Marco A. Bongioanni, USABack to Basics: Civil Affairs in a Global Civil-Military Network

by Major Jim Munene, USA, & Staff Sergeant Courtney Mulhern, USA