Medal of Honor Recipient Recalls Vietnam Service

Medal of Honor Recipient Recalls Vietnam Service

On his first day in Vietnam, 23-year-old Army Spc. 5 Jim McCloughan killed his first enemy soldier and survived an ambush that killed his lieutenant. It was 1969, and in the year that followed, McCloughan, a combat medic, would save the lives of many men and perform heroically.

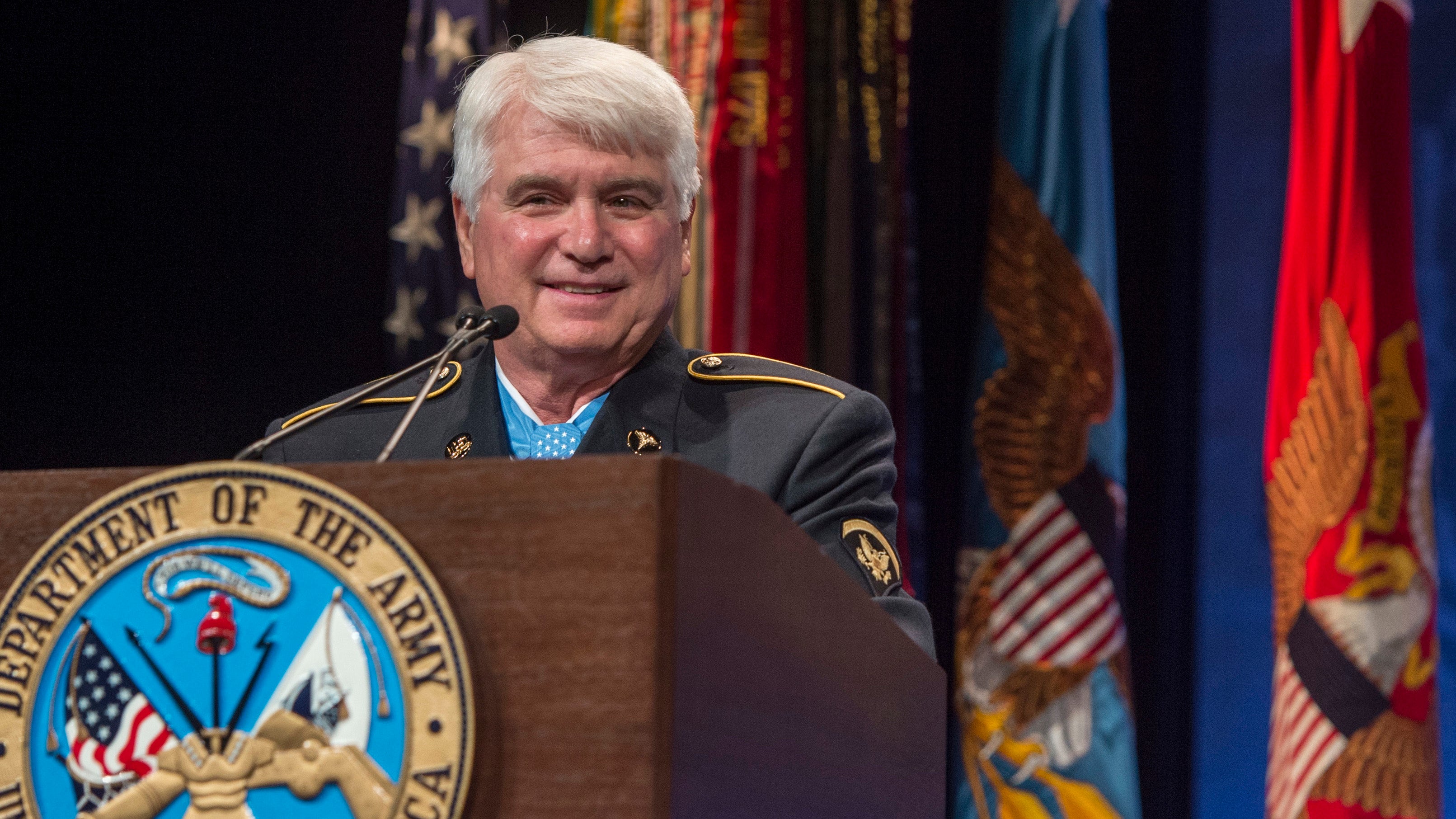

Now 71, McCloughan was only recently recognized with the Medal of Honor for his actions during a 48-hour battle in which he risked his life repeatedly to rescue nine comrades. He recalled some of the details of his time as an Army medic and his life as a young man in South Haven, Mich., during a recent interview at the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in Chicago with fellow Medal of Honor recipient, former Army Sgt. Allen J. Lynch.

McCloughan worked his way through high school and saved money for college by holding several jobs, but he saidthe one that best prepared him for combat was at a funeral home because he became accustomed to the sight of lifeless bodies.

He also worked in a factory and a frozen-food plant and picked apples and berries. During routine testing as part of his application to attend the U.S. Naval Academy, he was turned down when it was discovered he was color blind and couldn’t properly read flags.

“I picked a lot of bad strawberries,” he laughed. “They all looked the same to me.”

Drafted into the Army for a two-year commitment, McCloughan became a medic and was shipped out to Vietnamto join Company C, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment, in the Americal Division’s 196th Light Infantry Brigade. After hitting the ground and surviving his first ambush, not a day went by that he and his unit—a company that at the time had only 89 men—didn’t make enemy contact, he recalled.

“We moved before light each day…Then we’d stop about an hour after daylight to rest and eat,” he said. During the breaks he would make the rounds to change bandages, administer meds, and make sure everyone took their malaria pills. “There was a big orange one which would give you diarrhea. I found out if I took half of it on Monday and the other half on Tuesday you could avoid that.”

McCloughan gained a reputation for his skills as a medic and his agreeable demeanor. Soldiers would come to him from other platoons for help with some of the nasty conditions, such as impetigo, that can develop in the tropics.

He recalled meeting a soldier named Sgt. Hatton, a slow-talking guy with a crooked helmet and a missing tooth, and assumed he was a dullard. As time went on, though, McCloughan realized “Sgt. Hatton had a high school diploma, and I had a college degree, but Sgt. Hatton had a master’s degree in fighting the war, and Jim McCloughan was a kindergartner. I often say I was smart enough to know how dumb I was, and I did everything that man said. He just had a sixth sense.”

Wounded during the May 1969 offensive near Tam Ky and Nui Yon Hill, McCloughan continued to respond to calls of “Medic!” in spite of relentless heavy gunfire.

Upon his return to Michigan, he taught psychology, sociology and geography; coached football, wrestling and baseball; and raised a family. More than two decades passed before the “ghosts” of his time in combat began to haunt him—the faces of dying soldiers whose names he didn’t even know. The weight of their last words or the sound of their last breaths kept him up at night.

He sought help and said today’s soldiers shouldn’t be afraid to do the same.

“When I retired, that’s when the ghosts came in, the faces started coming back. Nothing can prepare you as a soldier to go to war,” he said. “At home, our funeral home vehicle was the ambulance, so I saw a lot of bad things. But that didn’t prepare me for war.”