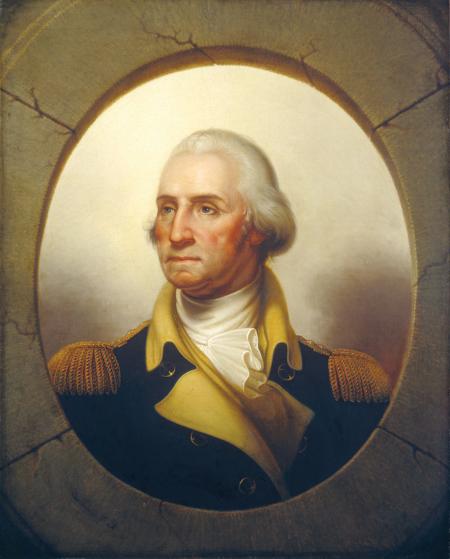

The Revolutionary War (1775–1783) was a seminal conflict that featured competing conceptions of operational art. Of all the notable generals, George Washington of the Continental Army and William Howe of the British Army exercised perhaps the most impactful operational art that shaped the course of the conflict.

While Washington described a defensive strategy that sought to avoid a general action or put anything at risk unless it was necessary to preserve the Continental Congress’s declared policy of political independence, Howe prioritized decisive action as the most effective way to end the war and achieve King George III’s commitment to a swift, yet not overly destructive, reintegration of the colonies. Howe enjoyed early dynamic victories but by war’s end, Washington’s patient practice of operational art—defined in modern U.S. Army doctrine as “the pursuit of strategic objectives … through the arrangement of tactical actions in time, space and purpose”—would prove more effective in enabling his government’s strategy and achieving policy objectives.

Beginning with the revolutionary side, the American path to victory proved long and arduous as the Continental Army persevered through repeated setbacks, and even near-disasters, to further the Continental Congress’s commitment to absolute victory through unlimited means. Washington, as articulated by historian David Hackett Fischer, remained “flexible in operational means” throughout the conflict as he sought to “win independence by maintaining American resolve to continue the war, by preserving an American Army … and by raising the cost of the war to the enemy.”

With the exception of initial successes in Boston and the final victory at Yorktown, Va., Washington mostly combined reluctant main force engagements with peripheral raids and guerrilla harassment that limited imperial opportunities. This strategy, which illustrated how Washington tailored his approach for that particular environment, aimed to preserve revolutionary unity while straining Parliament’s political will for a long and costly campaign.

The Continental Army’s engagements at White Plains, N.Y., and Trenton, N.J., in the fall of 1776 illustrated Washington’s vision of operational art. In the Oct. 28 battle at White Plains, which followed the strategic loss of Long Island and Manhattan to a stunning British offensive, Washington led a stubborn defense that blunted the invaders’ advance from Harlem. After first delaying the attack with an advanced guard of Massachusetts volunteers, Washington placed his 3,000 remaining men who had escaped Manhattan along the heights above the Bronx River. Then, as the invading forces attacked with cannon support, the Colonials bloodily repelled a series of fierce infantry assaults before retrograding toward the hill country of New Jersey.

The stubbornness of the outnumbered defenders discouraged further British pursuit and allowed the bloodied Continentals to escape intact and cross the Hudson River at the town of Peekskill. Once clear of immediate threats, the wounded force moved into the relative safety of Pennsylvania and New Jersey to recruit, rearm, and prepare for the next contest.

Army Remains Operational

This tactic, which contested British movements while retaining options to conduct a disciplined retreat, ensured that Washington’s Army, as the most tangible and symbolic manifestation of the flagging Revolution in form and function, remained operational for future engagements. Though certainly demoralizing, it would not be the last time the canny Virginian would prioritize the preservation of his forces, and therefore the political viability of his new nation, ahead of risking a more decisive decision.

The Colonials’ surprise attack on Trenton, two months after White Plains, emerged as a second manifestation of Washington’s operational art. With the revolutionary cause suffering from humiliating defeats in New York, Washington executed a challenging crossing of the Delaware River followed by an audacious raid against an outlying garrison of unsuspecting Hessian mercenaries at Trenton.

The targeted operation, which represented an inspirational alternative to risking a main force engagement with the consolidated British Army under Howe, resulted in the capture of almost 1,500 Germans and provided Congress with critically needed political momentum in the second year of the war. On Jan. 3, 1777, Washington built on this success with a wily raid against a garrison at Princeton, N.J., this time manned by British regulars, where they gained another minor, yet emotionally resonant, victory.

Both of these tactical actions reflected Washington’s astute understanding of the surrounding social and political setting where the Revolution could survive only so long as its “army in being” remained a visible representation of national unity. By preventing the destruction of his main force at White Plains and gaining symbolically important victories at Trenton and Princeton, he ensured maneuvers in the field directly supported the governing imperative, as stated in the Declaration of Independence, to remain free and independent states with full power to levy war. Washington would retain this operational approach, with minor exceptions, throughout the conflict as he combined opportunistic engagements and militia harassment to erode enemy readiness and morale.

The British Empire, as the intervening party, adopted a more limited approach to the North American problem. Howe’s vision of operational art reflected the challenges of projecting force across the Atlantic Ocean and cultural constraints of fighting fellow Englishmen that precluded strategies of annihilation frequently employed against native peoples. While he repeatedly postured to win decisive victories over Washington that never materialized, Howe, who served as British commander in chief in America from 1775 to 1778, launched brilliant offensives that captured New York City and Philadelphia.

In concert with a naval blockade, Howe secured the lower Hudson River and key coastal districts to isolate rebel centers. Appreciating London’s acute need for rapid victory due to competing fiscal and material requirements across the empire, he balanced reconciliation with honorable tactical operations, including joint efforts with the Royal Navy, which aimed to demonstrate the inevitability of British sovereignty.

Tactical Objectives Achieved

Howe’s capture of Long Island and Manhattan in August 1776 illustrated his conception of operational art in the American campaign. Seeking to simultaneously defeat Washington in the port city, isolate radicals in Massachusetts from the central and southern colonies, empower loyalists in the middle colonies, and compel Congress in Philadelphia to accept terms in the face of British superiority, Howe rapidly achieved his tactical objectives through rapid water crossings and aggressive flank marches. More specifically, he accomplished this feat of joint cooperation by first massing forces on Staten Island, then conducting a surprise amphibious landing on Long Island, attacking to dislodge rebel defenses in Brooklyn, and finally capturing Fort Washington in Manhattan.

The forceful and linear nature of the New York invasion directly supported London’s Colonial policy that demanded unequivocal submission. Though ultimately indecisive to the war’s outcome, the dynamic capture of the city served Parliament’s pressing need to, as argued by historian Piers Mackesy, “crack the unity of Congress and enable the people, under pressure of commercial blockade, to turn to the loyalists for a lead” and therefore avoid a prolonged and overly expensive campaign.

Ever mindful of the benefits of political conciliation on imperial terms, Howe complemented his tactical gains by hosting a peace conference on Staten Island with a Continental Congress delegation that included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. This meeting, though futile, reflected Howe’s multifaceted strategy to employ both punitive and diplomatic measures to increase loyalist ranks and, if possible, speedily conclude the war.

Howe continued his European-style military strategy by marching on Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress, with 15,000 men on Sept. 26, 1777, to definitively demonstrate imperial resolve. When Washington attempted a defense with 11,000 men on Sept. 11 along the Brandywine Creek in Pennsylvania, the British professionals skillfully outflanked them from the north and south to compel a general retreat. Though the Colonial main force once again escaped bloodied but intact, Howe subsequently occupied Philadelphia and forced the Revolution’s governing body to ignominiously flee for safer havens.

Despite this success, he failed to coordinate operations with Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne’s near-simultaneous invasion from the Province of Quebec, a British colony, along the Hudson River. The lack of unity contributed to “Gentleman Johnny’s” disastrous defeat at Saratoga and galvanized French and Spanish interest in supporting the revolutionaries.

Howe’s tactical actions, though not as decisive as the Crown had hoped for, aimed to catalyze political disunity and despair across the member states of the Revolution. By defeating Washington, occupying major urban centers and securing the Hudson River corridor, the general planned to isolate New England from the middle and southern colonies; galvanize loyalists in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania; and ultimately quicken the demise of the rebellion.

Unsuitable in New World

This combination of offensive maneuver and conciliation—which was tempered by Howe’s Whig and Protestant affinities for the Colonials—supported the policies established in London by George Germain, secretary of state for the North America department, which demanded complete and swift capitulation to George III. While seemingly proper for conducting warfare in Europe during the late 18th century, this linear alignment of politics, policy and tactical actions would prove unsuitable for the more diverse social and geographical terrain of the New World.

Despite noteworthy British military successes, Washington’s patient and flexible application of operational art ultimately proved more politically and strategically viable than Howe’s traditional and increasingly risk-averse maneuvers. Washington’s advantages in popular enthusiasm, international support, geographic distribution and territorial familiarity favored strategies of steadily eroding British resolve and capability while preserving the revolutionary government, army and cause.

Conversely, Howe’s focus on decisive battle and occupation of urban centers, though seemingly supportive of parliamentary priorities, proved ill-suited for decentralized social war in North America. If the colonial designed, as argued by historian Fischer, politically suitable actions that combined “boldness and prudence” and “large gains with small costs,” the imperialist pursued a more conventional campaign that supported, however inappropriate to the theater, his government’s demands for rapid and conclusive victory.

Dichotomies Evolved

The dichotomy between how each side aligned policy, strategy and tactics within the unique North American environment evolved as Washington and his subordinate commanders continued to implement, with notable exceptions, his chosen military strategy. While the Continentals’ determination to avoid potentially catastrophic battles both ensured the political survival of the Congress and benefited from absolute commitment to victory, British attempts to force a rapid conclusion were retarded by conceptions of more limited war with cultural, and even anti-monarchal, sympathies among senior officers. By the fall of 1781, when revolutionary forces and French allies finally isolated the empire’s main field army at Yorktown, Washington’s exercise of operational art, reminiscent of a hybrid Fabian strategy of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection, finally yielded decisive outcomes.

Ultimately, the British command’s failure to fully appreciate the social nature of the American theater, which Howe’s successors likewise underestimated, allowed the resilient Continentals and their patient leader the necessary time and space to create, as required by 21st-century U.S. Army doctrine, “military conditions necessary for the termination of conflict on favorable terms.” While both Washington and Howe employed variations of operational art to design military strategies and implement tactical actions that supported their respective government’s policy objectives, Washington’s approach better leveraged the unique nature of the people’s war in North America. If he demonstrated the potential for success when warfighting connects social, political and policy realities, then Howe, with far-reaching consequences, proved the perils of doing the same when echeloned miscalculation undermines the entire venture.