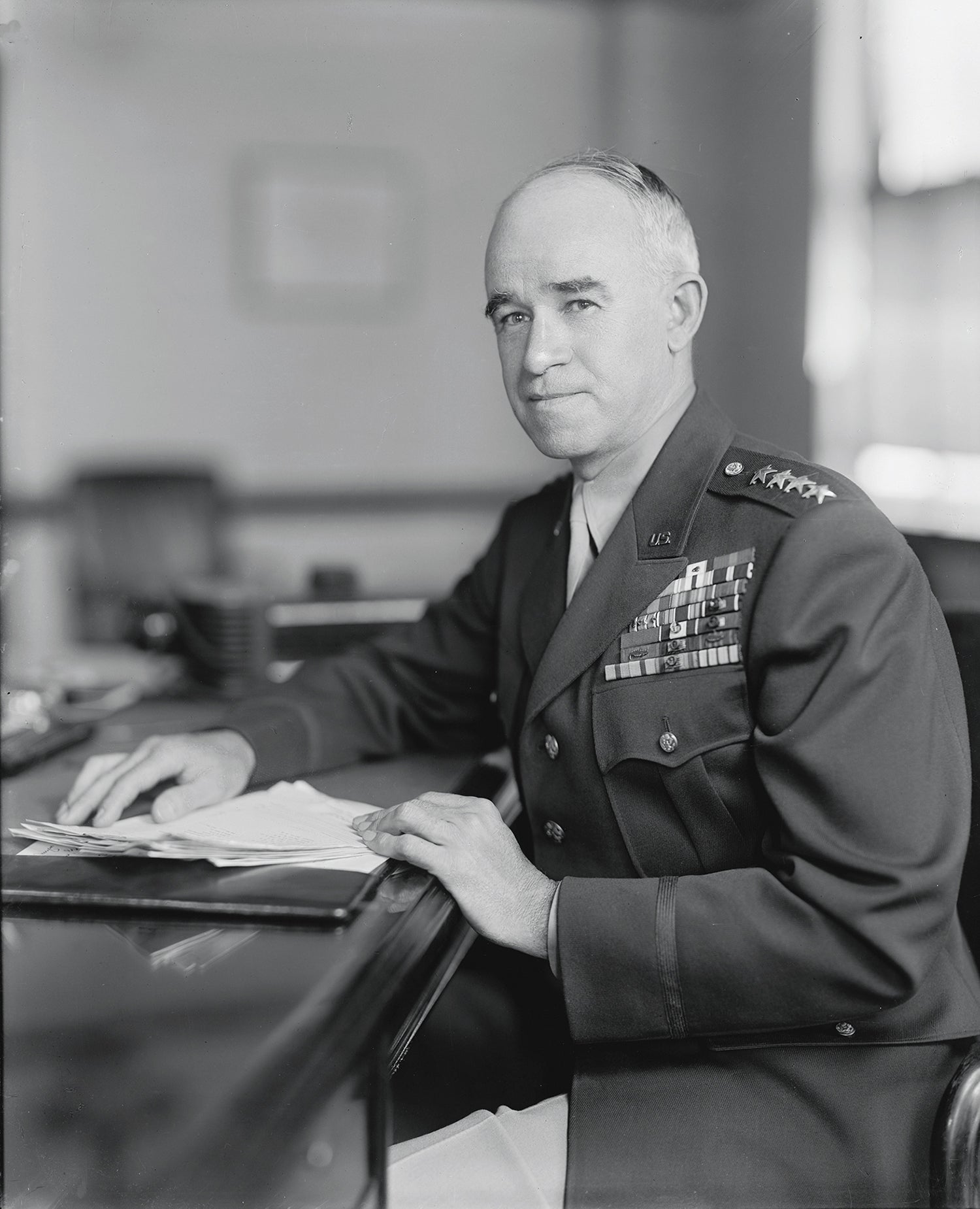

He was the fifth and last member of the U.S. Army to achieve five-star rank, a distinguished soldier who served as a senior officer in World War II. Known as “the GI’s General,” Omar Bradley accomplished much in his life. He also had a sterling reputation as leader of the 12th U.S. Army Group in the liberation of Europe, commanding 1.3 million troops at the conclusion of World War II.

One of Bradley’s major deeds, little known to the public, was his service as administrator of the Veterans Administration, now known as the Department of Veterans Affairs, at a time when millions of military personnel were returning from overseas deployments after World War II. As head of the VA, Bradley brought about the first major changes in the organization, modernizing and expanding medical care for veterans.

In May 1945, as the war in Europe came to a close, President Harry Truman selected Bradley to lead the VA, which dates to the Veterans Bureau of 1921. In the 1983 book A General’s Life: An Autobiography, by Bradley and Clay Blair, Bradley related the events surrounding his selection.

He wrote that he learned about his new assignment after he was summoned to NATO headquarters by Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who was then Supreme Allied Commander Europe.

Reluctant Acceptance

Truman had personally selected Bradley for the job, and Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall endorsed the assignment. Bradley, adamantly opposed to the idea, remembered: “Marshall correctly anticipated my reaction. … I knew absolutely nothing about the Veterans Administration.”

After discussing the situation with Eisenhower and being assured that “sooner or later I would be Chief of Staff [of the Army],” Bradley took the job.

Bradley met with Marshall and Truman in Washington, D.C., and they assured him “that I would retain my four-star rank and pay ($13,000) and my place on the Army’s seniority list.” Congress passed legislation in July 1945 that allowed Bradley to remain on active duty while leading the VA. On Aug. 15, 1945—one day after Japan surrendered to the Allies to end World War II—Bradley became the new VA administrator. He replaced Brig. Gen. Frank Hines, who had been administrator of the VA for 22 years but had fallen into disfavor.

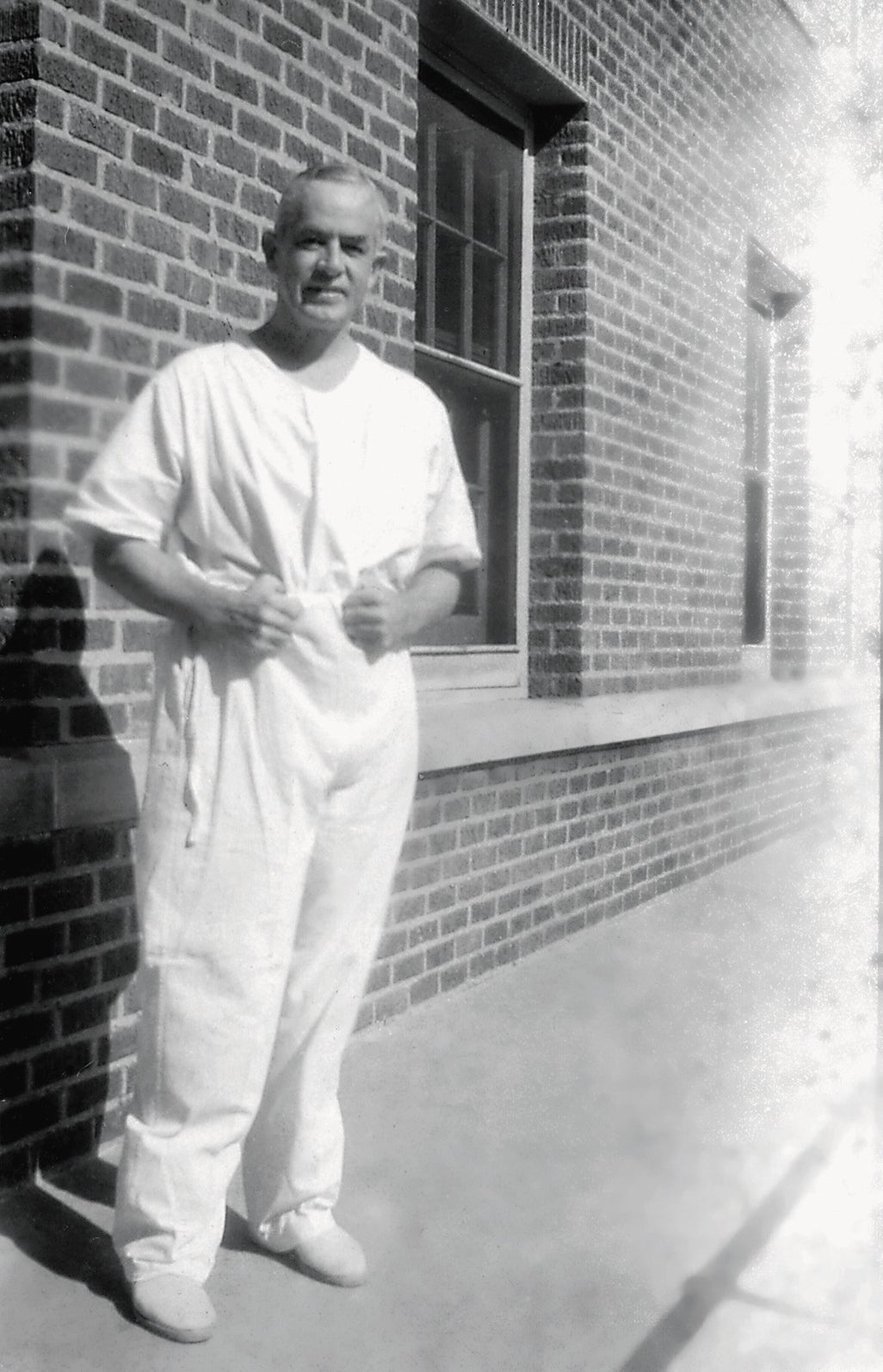

As Bradley took office, Truman directed him to modernize the VA, a much-needed development. Bradley noted this in his autobiography. “The most urgent challenge we faced at VA was … the quality of VA medicine,” he wrote. “The system had a shortage of physicians and hospitals.”

Big Challenge

Chaos reigned as the VA struggled to meet the needs of veterans being discharged from active duty, with almost 13 million men and women returning to civilian life from October 1945 to June 1946. Returning service members filled VA hospitals, which were unprepared for such an influx. At the time, the VA had slightly fewer than 84,000 beds spread across 98 hospitals in 45 states and the District of Columbia. Moreover, VA facilities were primarily located in remote areas.

Faced with these circumstances, Bradley’s military leadership skills came into play. He took charge with an emphasis on improving medical care. To begin the first major transformation in the history of the VA, Bradley brought with him the Army’s chief surgeon from the European Theater, Maj. Gen. Paul Hawley, as well as other officers from 12th Army Group to fill key positions across the VA.

Hawley became the VA’s chief medical officer and initiated a 10-year plan to develop a medical corps like in the Army, Navy and U.S. Public Health Service. Bradley and Hawley lobbied Congress for legislation to effect the change. Their efforts proved successful, culminating in Public Law 79-293, historic and far-reaching legislation that led to reform of the VA.

On Jan. 3, 1946, Truman signed the legislation, creating, among other things, the VA’s Department of Medicine and Surgery.

Rapid Expansion

Bradley undertook a massive effort to effect change. He decentralized operations, creating 13 branch offices that would each function as “a small-scale VA,” he said. Each branch had a deputy administrator who was responsible for making decisions and overseeing operations. As the decentralization effort got underway, Bradley began hiring additional personnel, increasing employee numbers from 65,000 in 1945 to 200,000 in 1947.

To accomplish such a gargantuan task, he bypassed civil service red tape to acquire physicians—including the first women—as well as nurses and other professional staff. Using the Veterans’ Preference Act, passed in 1944, many of the new hires were former military members.

As Bradley began his duties, most of the VA hospitals were in rural areas. He shifted many of the facilities to urban areas to be near medical schools, providing veterans with access to specialty care and cooperation. He was urged to do so by Hawley, who believed a formal affiliation with medical schools would allow the VA to benefit from interns and residents who could treat veterans.

New Connections

Affiliation with medical schools, formalized through the landmark 1946 Policy Memorandum No. 2, proved more difficult than originally thought. Historically, VA hospitals had been involved in pork-barrel legislation; elected officials sought to acquire a hospital and all the benefits that entailed for their areas. Thus, Congress and the public had to be convinced that affiliation with medical schools was a sound idea.

Geography also posed a problem. This could be overcome by building new facilities close to medical schools and expanding or relocating existing ones. During his tenure, 70 new hospitals and several additions were added, in Bradley’s words, “where we wanted them.” During this time, the VA established affiliations with 63 medical schools.

Since then, the VA has been involved in providing learning experiences for new physicians. Much of the research conducted in medical schools found its way into VA hospitals. In many cases, the medical schools awarded faculty status to the VA physicians and involved them in ongoing research.

In short, the affiliations proved to be beneficial to all parties. The VA now proclaims it is the largest health care training system in the country, providing training, residencies and fellowships to more than 120,000 trainees in more than 40 disciplines per year.

Distinguished Doctors

Additionally, during Bradley’s tenure, a Special Medical Advisory Group composed of distinguished physicians came into being. Through the efforts of Hawley, Dr. Charles Mayo of the prestigious Mayo Clinic became the initial chairman. The advisory group reviewed medical plans, made suggestions for improvements and assisted with affiliations with medical schools.

Bradley proved himself to be the right person at the right time in the critical moments following the end of World War II. Without his leadership and vision, and the able assistance of his hand-picked medical personnel, the VA likely would not be the system it is today. It has 171 VA medical centers and 1,113 outpatient care sites. As of June 2022, the VA had affiliations with 153 traditional medical schools and all 38 osteopathic medical schools. (Osteopathic medicine takes a whole-body approach to health.)

Bradley departed the VA on Dec. 1, 1947. He was justifiably gratified by his accomplishments. “I had sent hundreds of thousands of men into battle. I had heard the mournful cries of the wounded on the battlefield,” he wrote. “Nothing I have done in my life gave me more satisfaction than the knowledge that I had done my utmost to ease their way when they came home.”

Bradley would go on to succeed Eisenhower in the position he most coveted, chief of staff of the Army. In August 1949, he became the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He received his fifth star in September 1950.

* * *

Lt. Col. Wayne Curtis, U.S. Army retired, is a former Troy University, Alabama, business school dean. He holds a doctorate in economics from Mississippi State University.