All these years later, a particular smell or sound is enough to transport retired Lt. Col. Paul “Ted” Anderson to the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001.

“I think of it every day. It stays fresh with me every day,” Anderson said about the deadly attacks that killed almost 3,000 people at the Pentagon and in New York and Pennsylvania and launched what would become a 20-year war in Afghanistan.

As the nation prepares to mark the 20th anniversary of the attacks, Anderson, who received a Soldier’s Medal, the Army’s highest award for heroism in noncombat situations, for his actions at the Pentagon that day, said he plans to mark the day quietly.

“I choose to be by myself on 9/11, be with my family,” he said, adding he still regrets not being able to save more people that day.

For retired Lt. Gen. Patricia Horoho, former Army surgeon general and now CEO of the OptumServe federal health services firm and an Association of the U.S. Army senior fellow, memories from that day are “crystal clear, not just in our minds but in our hearts.”

“Twenty years later, I still remember that feeling of unity. I remember the pride of looking at the actions of countless people, whether it was New York or Pennsylvania or D.C., people gave up their lives for others. They put themselves in harm’s way to care for and protect others, people they didn’t even know,” said Horoho, who was a lieutenant colonel assigned to the Pentagon on 9/11. “There’s no greater gift than that.”

She added, “We should never forget there are still people grieving because they lost loved ones. Even though our lives have gone on, they’ve lost a piece of themselves.”

Coordinated Attack

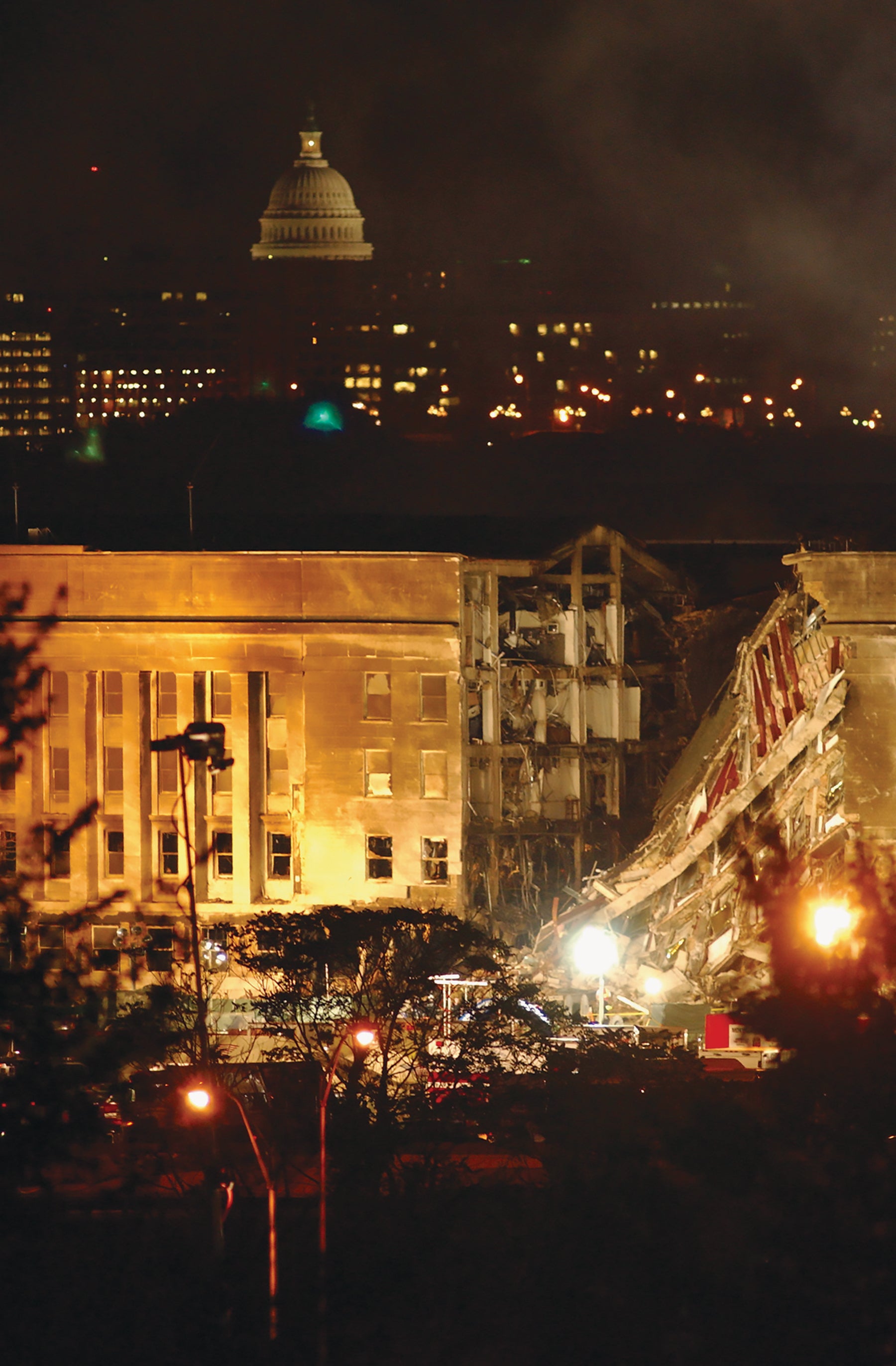

At 8:46 a.m. and then at 9:03 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001, two hijacked planes crashed into the World Trade Center in New York City. Shortly afterward, at 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the west side of the Pentagon, shearing through three of the building’s five rings.

Finally, at 10:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 93 crashed in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after the passengers, upon learning about the attacks in New York and on the Pentagon, tried to retake the plane.

In all, some 2,750 people were killed in New York, 184 at the Pentagon and 40 in Shanksville.

Since then, millions of Americans have stepped up to serve, fighting in Afghanistan and elsewhere to make sure such an attack never happens again. And the memory and legacy of those killed on 9/11—and of those who rushed in to save lives—will live forever, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley said during a ceremony last year to mark the 19th anniversary of the attacks.

The horrific acts of terrorism on that day were meant to disrupt the American way of life and destroy the idea that Americans are created free and equal, Milley said, according to DoD. “Instead of sowing division and strife, we … came together as a nation,” he said.

Suzanne McCollum, who worked in the Pentagon as an Army civilian, said 9/11 was her first “real experience of something truly terrible.”

The attacks changed everything, not just for the military but for her daughter, then a first-grader, and other kids like her, said McCollum, who is now AUSA’s registrar. “They’ve lived in this world where they’ve had 9/11 their whole lives,” she said. “The world definitely did change, and the world changed because of that day.”

No Warning

For so many, Sept. 11, 2001, started out as a regular day.

Anderson went to the Pentagon gym, then grabbed breakfast as he headed to his office in Army legislative affairs. When he arrived, a few of his colleagues were gathered around a television—the first plane had crashed into the World Trade Center’s north tower. “And then, boom, watching it, the next plane crashed into the second building, live on TV,” he said. “I literally threw up in my mouth.”

Walking to his office, he knew. “We were at war, and life is going to be different now,” he said. “I certainly didn’t know to what extent.” Then, “the building felt like it exploded,” Anderson said. “It felt like the foundation came completely up off the ground and slammed down.” He screamed for his colleagues to evacuate.

People poured out of the building. Anderson grabbed a pregnant woman who was frozen in place, terrified, and helped her outside. He then ran to the side of the building where the plane had hit. “You can see the point of impact, and the smoke is just now starting to billow, the fuel has gone through the building, and it’s starting to burn stuff,” he said.

As he took in the sight before him, Chris Braman, a staff sergeant, caught up to him. The men didn’t know each other, but they started running together toward the building, toward the fire. “We knew immediately that there were people inside that needed to be rescued,” Anderson said. “I didn’t know who these people were. It didn’t matter.”

’Don’t Let Go’

Anderson and Braman pushed into the building through a broken window. Their plan was to crawl to the corridor and yell for any survivors. Faced with thick, black smoke, “I told him, ‘Grab my ankle, and don’t let go,’ ” Anderson said.

Inching their way into the building, they found a woman and quickly got her out. They went back in and found a man on fire in the E ring corridor. “Chris had jumped on top of him and started smothering him, trying to put out the fire,” Anderson said. “I’ll never forget that, and I’ll never forget the fact that his eyes were wide open, but I could not see his pupils.”

The man was screaming: “There are people behind me, get the people out, they’re in the corridor.”

As Anderson and Braman prepared to reenter the building, they were stopped by firefighters who had arrived on the scene. “Now there’s a pushing match,” Anderson said, as he and a few others fought to go back inside. “They pushed us back, and we’re still having this argument, and all of a sudden, the building collapses,” Anderson said. “If we had been inside, we would’ve been dead. I owe my life to the Arlington County Fire Department. They are the true heroes.”

Anderson said he kept waiting, hoping to help. “There were literally hundreds of us not leaving because we knew this was going to be a rescue effort,” he said.

At dusk, Anderson went home. With no keys or car, he took the Metro. After a locksmith unlocked the door to his apartment, Anderson took a long shower. “That was the first time I cried,” he said.

Treating the Wounded

Horoho, a trauma nurse by training who at the time worked for the assistant secretary of the Army for manpower and reserve affairs, was in her Pentagon office when “the entire building shook. You could feel it sway back and forth.” From her office, about 150 yards from where the plane slammed into the building, Horoho said she felt “this calmness. It was a very strange feeling.”

Horoho ran to the site of the crash. “What I saw was this gaping hole in the Pentagon, and there was debris, there was smoke, there was fire,” she said.

She and a master sergeant started directing people who were running out of the building, and they started triaging the wounded. Using belts as tourniquets and whatever supplies she could get, Horoho started working on the injured. She and other colleagues assessed burns, started IVs and readied some of the injured for air evacuation. As she worked, “everything was very, very slow, and I remember looking at it and having this sense of, ‘This is what war feels like,’ ” she said.

Many of her colleagues wanted to help, she said, so they began organizing anyone with medical training into teams. “Everyone came together, regardless of your rank, your background, whether you were military or civilian, people united to help others,” she said. “It was a day our country showed the best of itself, and it was a day that was heartbreaking because of how many lives would never be the same and how many people lost loved ones.”

Horoho stayed until the next morning, she said, and she was there when firefighters unfurled a large American flag over the side of the Pentagon. “I never forgot it,” she said.

‘You Guys Have Been Hit’

On the other side of the Pentagon, McCollum and her colleagues were trying to pull up information online after hearing that planes had crashed in New York. Their division of the Army legislative liaison office had moved to new offices just two days before so their original workspaces could be renovated.

McCollum’s phone rang. It was a friend who worked in nearby Crystal City. “She said, ‘You guys have been hit. A plane came in, you guys have been hit,’ ” McCollum said. “I said, ‘What are you talking about? It was New York.’ I was so confused. It was so unbelievable.”

Because their new offices were partly underground and on the other side of the building, no one heard or felt anything, McCollum said. It wasn’t until they got to the parking lot that they saw smoke and police, firefighters and other first responders, she said. “The smoke was just billowing, billowing,” she said. “We were just kind of in shock.”

McCollum said she remembers feeling grateful that her teammates survived. “People were calling us heroes for being there, but I felt like, ‘No, I didn’t do anything. I left,’ ” she said. “I just happened to be at work.”

A Way Out

Col. John Davies was talking to a fellow officer in the doorway to his office when the plane crashed into the Pentagon. “It was a deafening explosion,” said Davies, who was the deputy director of military personnel management in the Army personnel directorate. “I just figured it was a bomb.”

Immediately, his instincts kicked in. “People were getting underneath their desks because they thought it was an earthquake, and we were grabbing people and pushing them toward the exit to get out of there,” he said.

After helping move the first group of people to safety, Davies, who retired from the Army in 2003 and is now AUSA’s membership director, went back toward his office. “I laid down on my stomach and yelled, ‘If you can hear me, come toward the sound of my voice,’” he said.

When the smoke became too thick, Davies moved to the A ring, toward the center of the building, where he came across a colleague who had been seriously burned. Davies and others quickly moved the man to safety, scooping up as many water bottles as they could from a nearby snack bar to help soothe the man’s burns.

Davies and a few others decided to try to get back to the E ring to see if they could find anyone else who needed help, but the smoke was too heavy, so they began working the corridor between the C and D rings, Davies said. They ran from office to office, checking for survivors. The group eventually made its way out of the building after seeing firefighters. “We knew it was better to leave and let them do their thing,” he said.

Now outside, Davies didn’t have his wallet, keys or phone. “I had $2 in my pocket from change from a cup of coffee I’d gotten that morning,” he said, so he took the Metro to his wife’s office in Washington, D.C. The couple made their way home, where Davies began calling members of his team, “trying to locate all our people, see who was missing out of the G-1 and who was injured,” he said.

By the time he was done, almost two dozen people from the Army personnel directorate had been killed, and another two dozen were injured or in the hospital, Davies said. As the team began to grapple with the loss of so many colleagues, Davies said, they relied on each other, attended every funeral and made sure to check in with one another.

Focusing on Work

Going back to work also helped, he said. “Getting right back to work the next day, the knowing that people counted on us to be able to recover and carry on with what the Army was going to be faced with, it gave us something to focus on,” Davies said.

Twenty years later, Davies said he looks forward to reuniting with some of his teammates from that time. “A milestone anniversary like 20 years is certainly important,” he said.

He often thinks about how America came together after 9/11, and he also remembers how his training kicked in that day—a lesson he tries to impart to Civil Air Patrol cadets when he volunteers with the group. “You just react without thinking, to do what you have to do,” he said.

Horoho also said she often thinks about how the country united after the attacks, something she hopes “our nation can embrace again.”

Anderson said he’s been asked if he feels honored to be called a hero. “I always felt that I had failed, that we had left people behind,” he said. “They were right there in the corridor, and all we had to do was get to them, and we didn’t get to them.”

There is one thing he is proud of, Anderson said. “On September the 12th, in the dark, 18,000 people started reporting to work in a burning building,” he said. “They knew we were at war, that their battle station was in that building, and they came to work in that burning building.”

Over the years, Anderson, who retired from the Army in 2003, got some “good therapy” and learned to compartmentalize his feelings about the day. “If you dwell with it, it will consume you; it will take control of you,” he said.