As he prepares to step down June 30 as president and CEO of the Association of the U.S. Army, retired Army Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan is deeply concerned about the future. Not his, but the Army’s.

“We may be living a tragedy,” said the 78-year-old Quincy, Mass., native, who worries about an undermanned and under-resourced Army being called upon to send soldiers into battle who may be less than fully prepared, less than fully armed, and at less than full strength. “The Army has changed, and I am not sure it is for the better,” Sullivan said. “I see the Army being emasculated.”

Sullivan spent more than 36 years in the Army, rising to become the 32nd Army chief of staff. He then spent more than 18 years heading AUSA, an educational nonprofit dedicated to being a voice for the Army and its soldiers. Retired Army Gen. Carter F. Ham is Sullivan’s successor at AUSA.

He’s Seen This Before

Sullivan speaks with experience when he expresses trepidation about the Army’s future. When he was chief at the end of the Cold War, he was ordered to oversee what amounted to a 40 percent reduction over four years in the Total Army. He did this while attempting to maintain morale and a sense of purpose while also seeing the Army deploy on unexpected contingencies to Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti and the Balkans; and also with Hurricane Andrew, then the most destructive hurricane in U.S. history.

One of his goals throughout that process in the 1990s was to prevent the Army from losing combat prowess by turning to technology, tactics and training to keep soldiers sharp.

Sullivan described his role as chief, and that of his immediate successors, as cutting Army spending so the money could be used for something else. “I don’t know where it went,” he said. “It went somewhere.”

“At some point, we are going to have to accept the fact that we cannot do what we are being asked to do without more manpower,” Sullivan said. Also, “we are not modernizing. There is no money to modernize the Army.”

“I believe the essential nature of the Army has remained constant since the beginning. It is the soldier. The soldier is the weapon. He or she is the answer. They are the ones who adapt on the battlefield,” Sullivan said. “Ultimately, success will rest on the shoulders of the men and women who had the courage to serve. I believe that.”

Shake-ups, not Breakups

Sullivan also believes current Army leaders are facing today’s challenges as well as can be expected, but he worries about putting too much strain on the force. “The real challenge is to hold it together spiritually,” Sullivan said.

Cutting the Army between wars is akin to an American pastime, like baseball and hot dogs. “It is almost built into the American character. When you’re not at war, they don’t like the Regular Army,” he said of politicians. “It’s almost an American precept that we do not keep a big Regular Army.”

Today’s Army is very different. “The Army is not big enough,” he said, and part of the burden is falling on families. “We are no longer forward-based. We are projecting power from the U.S., and that is adding a burden to the Army and especially to Army families who are not going with them. It seems like we are always on the move or getting ready to go, or we are retraining when we get back to go again.”

“I liked those guys,” he said, recalling the NCOs who were his instructors during basic armor officer training at Fort Knox, Ky. “The glue that connects all of it together is the noncommissioned officer,” Sullivan said. “We have a world-class Noncommissioned Officer Corps, and we’re very fortunate to have it.”

In April, Sullivan became the first person to be named an honorary Sergeant Major of the Army in a ceremony that left him greatly touched. “This really means something to me,” he said. Sgt. Maj. of the Army Daniel A. Dailey said Sullivan deserves the recognition because he is “a great mentor, a great leader and a great soldier through his entire life, who still to this day represents who we are and what we stand for.”

Sullivan Joins AUSA

Sullivan became AUSA’s 18th president in 1998, about two years after retiring from the Army and after he tried a corporate job. “I didn’t like it from the outset, frankly,” he said of the job. “I just wasn’t satisfied.” Working for AUSA, however, “was what I wanted to do with my life.”

“People get to choose how they live their life. This is how I wanted to live my life, as a soldier,” Sullivan said.

He stayed with AUSA because he liked the work and the mission, especially the educational development aspects. “But I think it’s time for me to go, because most of the people” he knew “are all retired. I am an ancient artifact. I don’t want to be known as a guy who didn’t know when it was time to leave.”

Leaving doesn’t mean sitting still, however. Sullivan is the chief organizer of an AUSA-sponsored initiative called Guiding Principles for the 21st Century. The idea is to create a bipartisan framework for U.S. domestic and foreign policy, similar to what the 1941 Atlantic Charter did in crafting foreign policy objectives for the U.S. and Great Britain and ultimately, for the other nations that signed onto the principles.

The goal is to create a list of about eight policy goals that would strengthen the U.S. role as a global leader and shape the future. They include respecting national sovereignty, supporting the right of people to choose their own form of government, and supporting human rights. A working draft addresses support for peaceful resolution of international disputes; and international cooperation to reduce crime, corruption, terrorism, genocide, famine and pestilence.

The hope is to have approved guiding principles available for review this summer, in time to be shared during the presidential elections.

Permanent Home for Army Story

Additionally, Sullivan’s post-AUSA life will involve a full-time effort to get the National Museum of the U.S. Army built at Fort Belvoir, Va., bringing to an end a 202-year effort to have a place to showcase the Army’s role in American history. Without the museum, “we don’t have a way to tell the Army story,” said Sullivan, chairman of the board of the Army Historical Foundation. “You can’t think of the history of the United States of America without thinking about the Army. We have been here in one form or another since before there was a United States of America.”

__________________________________________________________________

Sullivan’s Service Includes Sharing Stories of Heroes

During his many decades of service both in Army uniform and as president and CEO of the Association of the U.S. Army, retired Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan has met and spoken to a countless number of soldiers.

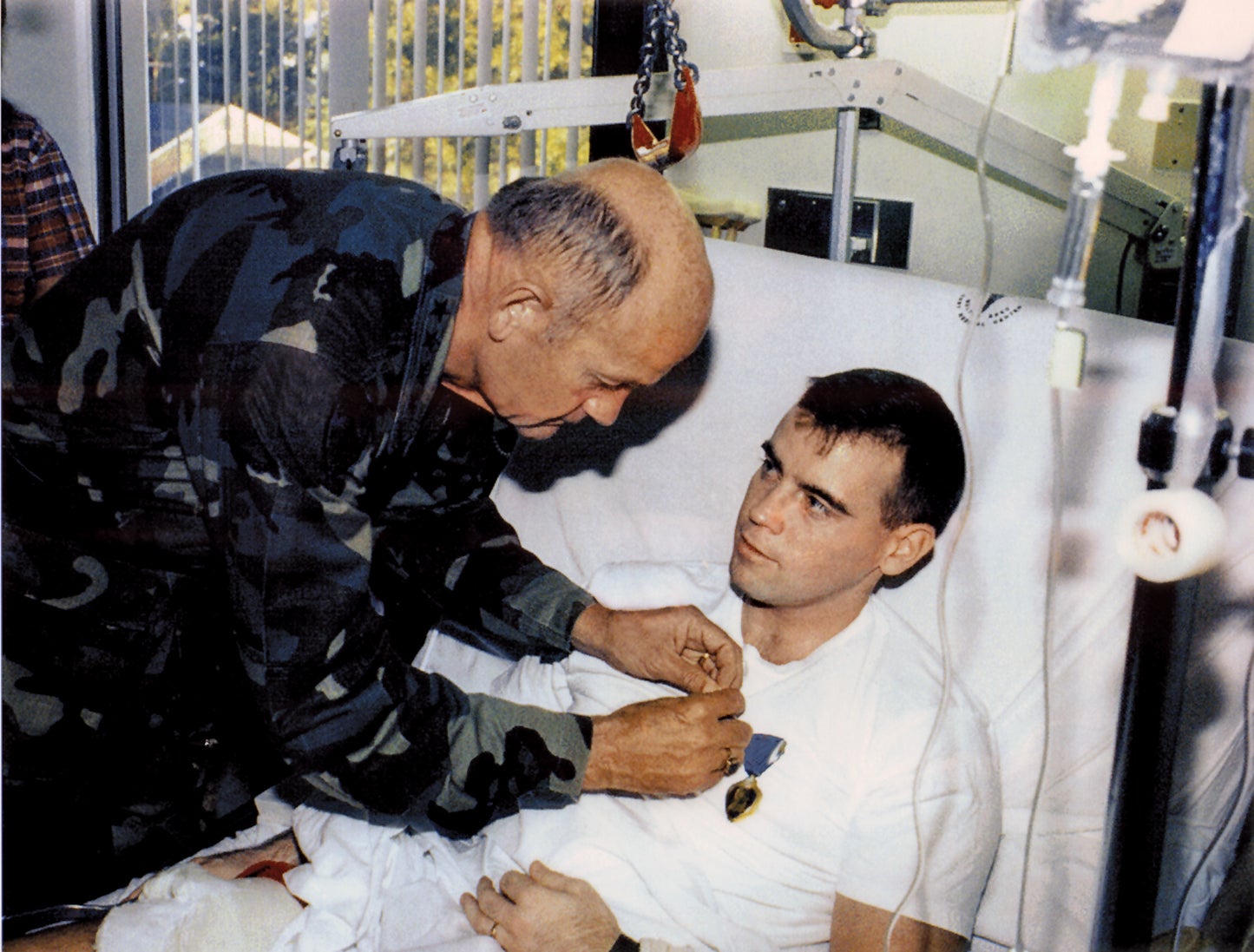

Some stand out in his mind more than others. As Sullivan prepares to retire from AUSA, he talked about two soldiers who made indelible impressions on him. One is former Sgt. Christopher Reid, whom Sullivan met in late 1993 at Fort Drum, N.Y. Reid’s unit in the 10th Mountain Division was being welcomed home from Mogadishu, Somalia, just a couple of months after helping to rescue other U.S. troops following a helicopter crash in the city.

“They come into the gym,” Sullivan recalled. “The fami- lies are there, the signs—everybody is charged up. I was up on a little stand, and I noticed down to the right, a soldier comes into the formation on crutches. So we had a short ceremony, then I went down and found

this kid.”

It was Reid, a fire team leader who had been severely wounded in Somalia when a rocket-propelled grenade blew off his right hand and shredded his right leg. He told Sullivan he was compelled to come to the ceremony to stand “one last time” with the men he fought with.

“Then he said, ‘You know, sir, knowing what I know now, I’d do it again,’” Sullivan recalled. “And I said to myself: ‘Where do we find these guys?’”

Another soldier who made an impression on Sullivan also was wounded in Mogadishu. He was an “E-4 named Ly, a Vietnamese kid, weighed about 98 pounds soaking wet,” Sullivan said.

They met in October 1993 when U.S. troops wounded in Somalia were returning home through Andrews Air Force Base, Md.

“He’s laid out on a stretcher; he’s got on an Army T- shirt flecked with blood,” Sullivan said. “I reached down and looked at his wound tag and said, ‘Hey, Ly, I see you’re a member of the 41st Engineers. What’s it like to be a combat engineer?’ He said: ‘Sir, I’m not a combat engineer. I’m a sapper.’”

“I’m there in my greens, all my medals, my stars, every- thing. And I said to myself: This kid could give a sh– less. God love him … the American soldier.”

After he spun a few such stories earlier this year during a visit to Fort Bragg, N.C., Sullivan said a listener asked, “How many people do you know?”

“I said, ‘I don’t know how many people I know. But what I do know [is that] the Army is people. … If you don’t tell their story, nobody’s going to tell their story.’”

—Chuck Vinch

__________________________________________________________________

Groundbreaking is expected later this year, with the entire museum project completed in 2019. “I have already raised a hefty amount of money to put on top of what’s already there,” Sullivan said. “I’m finding there actually are people who are equally committed to having this museum.”

He said the Army’s story “is so complex that it is hard for anybody to understand it unless you see some things,” which is the purpose behind building a museum. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark A. Milley “doesn’t have a place where he can take people, visitors, and say, ‘Look, this is what the Army has done for America.’”

Sullivan said the Army was good for him. “I came to grips with who I was and who I wanted to be,” he said. “Did it hit me like a lightning bolt? No. It came over time.”

A graduate of Norwich University, Vt., Sullivan was commissioned as a Reserve officer but quickly realized he wanted to become a Regular officer and stay for a career. “I was really starting to think this Army was great,” he said of the point in his career when he became a tank platoon leader in Korea. “I loved it because it was soldiering 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

The big jump in his career came after his second tour in Vietnam, with consecutive assignments as G-3 for VII Corps under one of his mentors, Lt. Gen. Julius W. Becton Jr., and later as a brigade commander at Fort Riley, Kan.

“It was all part of the education of Gordon Sullivan to the complexity of command at the top, and how it is a team effort,” Sullivan said. “It is where I began to learn what it meant to say ‘team.’ So what is the secret sauce? It’s no mystery. The Army is people. And if you aren’t willing and able to listen to people … and by the way, listening may require dialogue to bring out the real issue.”

*Senior Staff Writer Chuck Vinch contributed to this article.