Pearl Harbor attack: 75 years ago, 2,403 Americans killed

Pearl Harbor attack: 75 years ago, 2,403 Americans killed

In the decades that followed World War II, the attack on Pearl Harbor had faded somewhat in the American public’s memory.

The attacks of 9/11 changed all of that. “All those bad memories surged forward again,” said James C. McNaughton, who served as command historian for U.S. Army Pacific from 2001 to 2005. Today, he is the director of Histories Division at the Army Center of Military History.

Just weeks after the 9/11 attacks, McNaughton attended a ceremony commemorating the 60th anniversary of Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. At the ceremony, he found himself among a large number of World War II veterans and Pearl Harbor survivors. Both attacks, McNaughton believes, were on all of their minds.

McNaughton attributes the fading memory of the events that transpired at Pearl Harbor 75 years ago, in part, to World War II veterans’ reticence to share their own wartime memories.

McNaughton’s own father, who served as a marine participating in the Central Pacific campaign, was reluctant to discuss his wartime experiences.

Three missions

While the story of the devasting Japanese air strike on U.S. naval forces that day has been well documented, McNaughton observed, few people know the Army’s role.

At the time of the attack, 43,000 soldiers were in Hawaii, where they were tasked with three primary missions, the first of which was to protect the territory of Hawaii from an invasion. (Hawaii remained a territory until statehood in 1959.)

“It was not beyond the realm of possibility that the Imperial Japanese Navy could carry out an invasion,” he explained. “They didn’t do so, but the Army could not be sure, so it deployed combat troops to defend the beaches.”

The second was to defend the fleet with coast artillery and anti-aircraft artillery. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall Jr. had made it very clear to the highest ranking Army officer, Lt. Gen. Walter Short, commander, U.S. Army Hawaiian Department, that his No. 1 mission was to protect the fleet, McNaughton said.

Before 1940, the U.S Pacific Fleet had been based in San Diego. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, for his own diplomatic reasons, had ordered the Navy to re-base itself at Pearl Harbor, according to McNaughton. The move added to the Army’s responsibilities.

The third mission was training, he said.

By 1940, World War II had already engulfed much of Europe and the Pacific, and Americans were beginning to realize their involvement might be inevitable. For the Army’s part, they were organizing and training units – from squad to regiment and division. They were even conducting field exercises and basic training concurrently.

Besides ground forces, the Army at that time also included the Army Air Corps. “They were trying to train flight crews and mechanics and use the limited aircraft they had on hand,” McNaughton said. “This was a fairly green Army.”

The National Guard and Organized Reserve had been mobilized as recently as 1940 and the draft, known as the Selective Training and Service Act, wasn’t instituted until Sept. 16 that same year.

In 1940, fewer than 270,000 soldiers were on active duty. That number would climb to about 7 million by 1943.

Setup for failure

By late 1941, the Army in Hawaii was trying to juggle all three missions. “In my judgment, they couldn’t do all three,” McNaughton said. “They spread themselves too thin. Ultimately they failed.”

Coordination between the services was also poor, he said. The Army and the Navy on Hawaii had separate chains of command, and they engaged in very little coordination, at least in practical terms.

Early Sunday morning, the day of the attack, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet based at Pearl Harbor and his counterpart, Short, were preparing for their weekly golf game, McNaughton explained. Every Sunday morning, the two flag officers would play golf, enabling them to “check the box” for joint coordination.

“Well, you need more than that,” McNaughton said. “And that’s what they didn’t do.”

In 1946, according to the Army’s official history, “Guarding the United States and Its Outposts,” the Congressional Pearl Harbor Joint Committee concluded:

“There was a complete failure in Hawaii of effective Army-Navy liaison during the critical period and no integration of Army and Navy facilities and efforts for defense. Neither of the responsible commanders really knew what the other was doing with respect to essential military activities.”

Senior Navy and Army leaders relieved Kimmel and Short of their commands within days after the attack, and they were never fully exonerated.

Early warning signs

Failure of the services to coordinate had real consequences on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941.

In the pre-dawn hours, a submarine periscope was spotted near Pearl Harbor, where there shouldn’t have been any submarines. At 6:37 a.m., the destroyer USS Ward dropped depth charges, destroying the submarine. The incident was then reported to the Navy chain of command.

Meanwhile, at the Opana Radar Site on the north shore of Oahu, radar operators Pvt. Joseph L. Lockard and Pvt. George Elliott detected an unusually large formation of aircraft approaching the island from the north at 7:02 a.m.

At the time, radar was experimental technology, and operators manned it just 3 to 7 a.m., McNaughton said. Usually, the radar was shut off at 7 a.m. for the rest of the day. It was only because the truck that took Lockard and Elliott to breakfast was late that the radar was still on at 7:02 a.m.

The operators had never seen such a large number of blips before, according to McNaughton. They called 1st Lt. Kermit A. Tyler, an Air Corps pilot who was an observer that morning at Fort Shafter’s Radar Information Center.

“Don’t worry about it,” Tyler told them. He had heard that a flight of B-17 bombers was en route from Hamilton Field, Calif., that morning.

If the Army and Navy had been in communication, McNaughton believes, they might have recognized the signs of the coming attack: the sighting of a large aircraft formation coming in from the north and the sighting of a submarine at the mouth of Pearl Harbor.

“If you put those two together, you might want to put everyone on full alert. But they didn’t,” he said. “There was no integration of intelligence from the two services. So the only warning they got was when the bombs started to fall.”

Attack commences

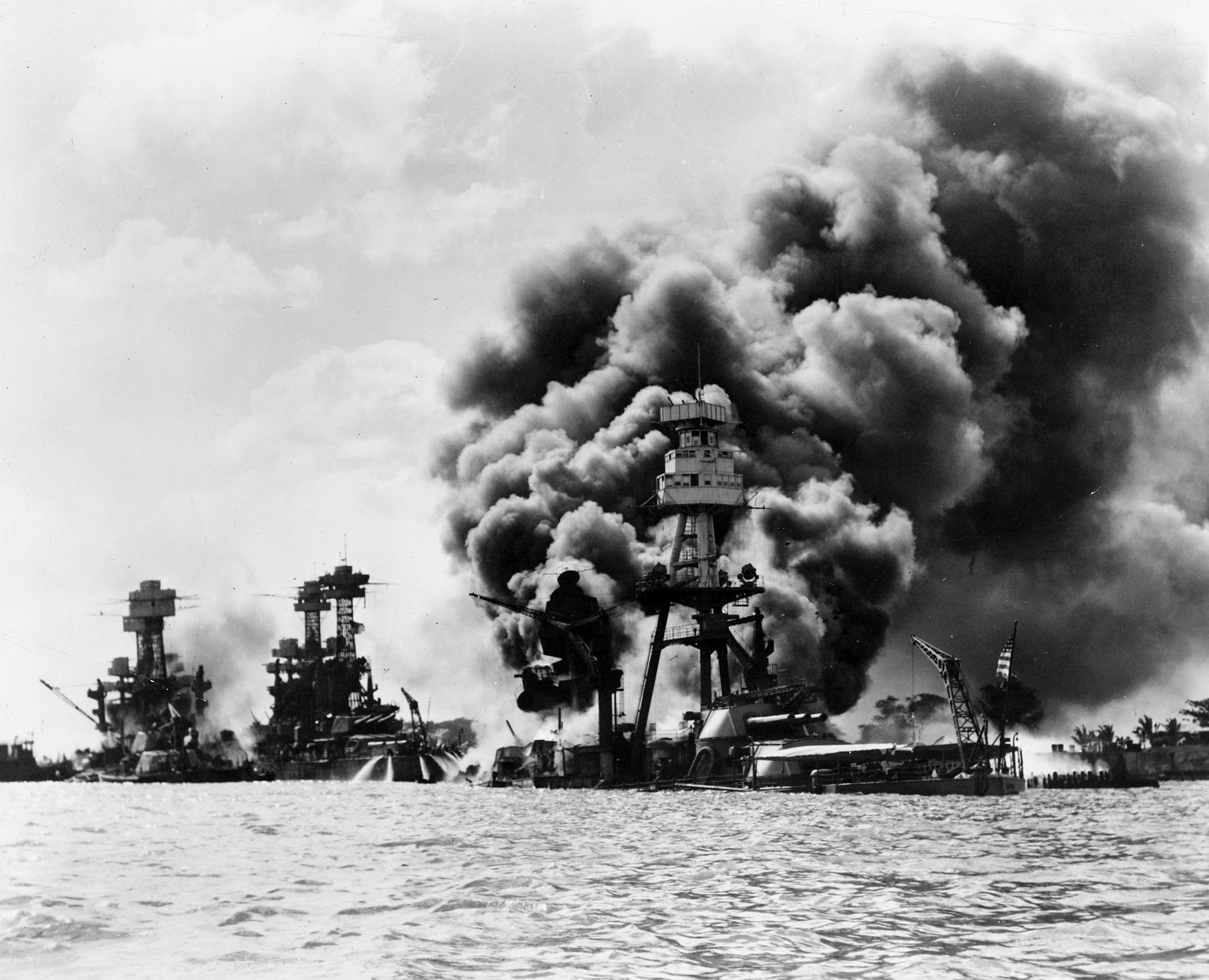

The first of two waves of some 360 Japanese fighters, bombers and torpedo planes began the attack at 7:48 a.m., having launched from six aircraft carriers north of Oahu.

While many of the Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft attacked the fleet, other planes attacked all the airfields on the island, including Wheeler Field next to Schofield Barracks.

Among the 2,403 Americans killed, 2,008 were sailors, 218 were soldiers, 109 were marines and 68 were civilians, according to a National World War II Museum Pearl Harbor fact sheet.

Of the aircraft destroyed, 92 were Navy and 77 were Army Air Corps. Two battleships were destroyed and six were damaged; three cruisers were damaged; one auxiliary vessel was destroyed and three were damaged; and three destroyers were damaged, according to the fact sheet.

The carriers USS Enterprise, USS Saratoga and USS Lexington were out on maneuvers and were not spotted by the Japanese.

Within minutes of the attack, Navy anti-aircraft guns opened up. The guns were firing at planes in all directions. A number of stray Navy anti-aircraft gun rounds fell in populated areas of Honolulu, killing more than a dozen civilians.

However, the Army’s anti-aircraft gunners at first struggled to engage the enemy because their guns were not in firing positions and the guns’ ammunition was in a separate location, where it was under lock and key.

“You can imagine them looking for the ammunition sergeant who had the keys at 8 a.m. Sunday,” McNaughton said. “It took them a while, but some guns did eventually get into action.”

Why weren’t the Army guns in position?

Short complained afterward that he had received ambiguous guidance from Washington. He said he was instructed to be prepared to defend against an attack but not to alarm the civilian population, which setting the anti-aircraft guns in position might have done.

Even so, the Army, with four regiments of anti-aircraft artillery in Oahu, had rehearsed defense against air raids. “They knew it was a possibility,” McNaughton said. “But certainly they were caught by surprise.”

Nevertheless, soldiers found some means to counter-attack. At Army installations, Army men fired back with machine guns and other weapons at attacking enemy dive bombers and fighters, according to “Guarding the United States and Its Outposts.”

One of the soldiers who lived through that day at Schofield Barracks was Cpl. James Jones, who later depicted the chaos in a 1951 novel, “From Here to Eternity,” which was eventually made into a movie that garnered eight Academy Awards.

As for the Army Air Corps, they eventually got 12 aircraft in the air and shot down a few Japanese planes. Ultimately, though, the Army Air Corps was overwhelmed. The vast majority of soldiers killed in action that day were in the Army Air Corps, McNaughton noted.

The Army Air Corps flight of 12 B-17 Fortress Bombers – the aircraft that Tyler thought the radar operators had spotted –arrived in the middle of the attack. They were unarmed and almost out of fuel.

The aircraft landed at various airfields, and one landed on a golf course. One of the aircraft was destroyed by the Japanese, and three were badly damaged, according to “Guarding the United States and Its Outposts.”

“Just imagine, it’s supposed to be a routine peacetime flight and you show up in the middle of the biggest air battle the U.S. had ever seen,” McNaughton said. “Not a good situation.”

No plan for invasion

In fact, the Japanese never planned to invade Hawaii, McNaughton said. Rather, they wanted to cripple the U.S. Pacific fleet so it could not interfere with their plans to seize European colonies in Southeast Asia.

At the time, Army and Navy signals intelligence personnel were working hard to break the Japanese code, he said. They were intercepting communications and decrypting what they could, but the communications they intercepted gave no clear warning of the impending attack.

What the Japanese misjudged was the tremendous anger of the American people, which gave President Roosevelt and Congress the excuse they were looking for to declare war against Japan as well as Germany, McNaughton noted.

In the aftermath of the attack, the Army immediately took over the territory of Hawaii, declaring martial law, which lasted until October 1944. In this unprecedented situation, all local police, courts and government operated under Army supervision. The Army, Navy and FBI placed the local Japanese-American population under close surveillance and placed many community leaders under arrest.

During the war, the Army soldiers in Hawaii – as in various places along the coasts on the U.S. mainland – never had to fire artillery guns to repel an enemy fleet, McNaughton said. The Army eventually disbanded the Coast Artillery branch, and today it uses sophisticated air and missile defense, in coordination with the other services.

Among the lessons to be taken from Pearl Harbor attack, according to McNaughton, is the crucial importance of operating as part of the joint force. Another is that of striking a fine balance between training and readiness. “You just don’t know when your unit will be called to mobilize,” he said.

The forced internment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast in 1942, in the aftermath of the attack, was a further tragedy.

“It was really painful to the Japanese-American community at the time,” he said.

Adding, “The vast majority of Japanese Americans were loyal citizens, those who had the opportunity fought for America. And many of those died for their country.”