The Medal of Honor is the most revered and highest award for military valor in action. Since the decoration’s inception in 1861, for the Navy, the medal has been bestowed in the name of Congress 3,530 times, including on one woman and on 19 individuals who have received multiple awards.

The standards to award the medal have evolved over time. On July 25, 1963, Congress approved guidelines and established the current criteria to recognize “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of one’s life above and beyond the call of duty.”

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton first bestowed the medal on the surviving members of a Union Army scouting detachment known as Andrews’ Raiders on March 25, 1863. Pvt. Jacob Parrott holds the distinction of being the medal’s initial recipient.

Though each honoree possesses a unique story and deserves the gratitude of the nation, three recipients illustrate that heroism can overcome prejudice.

Desmond Doss

Pfc. Desmond Doss is perhaps one of the most unlikely recipients of the Medal of Honor. Born in Lynchburg, Virginia, on Feb. 7, 1919, Doss was raised in a strict Seventh-day Adventist family. Entering the Army on April 1, 1942, Doss was classified 1AO, meaning conscientious objector (CO) available for noncombatant military service, as Seventh-day Adventists are prohibited from working on the Sabbath. The Army did not have a separate category for a noncombatant other than CO, so Doss became a medic with the 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division.

Following basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, Doss’ company shipped to the Pacific in mid-1944. Doss’ support of his fellow soldiers on Guam and subsequently on the island of Leyte in the Philippines, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s initial landfall on the Philippine Islands, was exceptional, and he received a Bronze Star with V device.

The 77th Division relieved the 96th Infantry Division on the island of Okinawa on April 28, 1945. It was on Okinawa that Doss encountered his rendezvous with destiny.

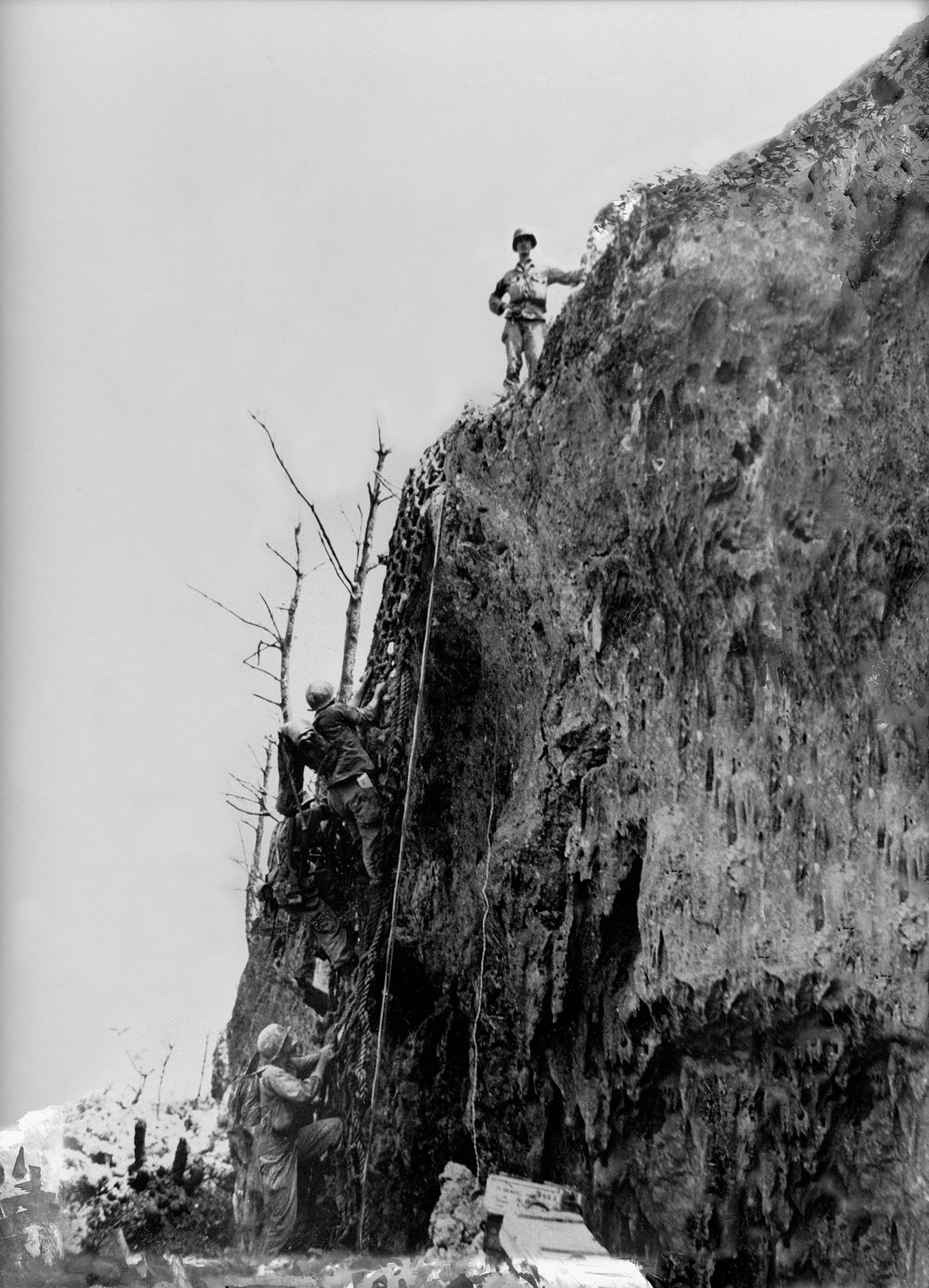

Stretching across the island was a 400-foot cliff called the Maeda Escarpment. Doss’ company’s mission was to scale the ridge and eliminate the enemy on the reverse slope of the escarpment. The climb was exceedingly difficult, with the last 30–40 feet nearly vertical.

On May 2, 1945, Doss reached the summit with 155 soldiers from Company B. At the top of the escarpment, Company B encountered heavy resistance. When the commander ordered his men to retreat on May 5, Doss refused to abandon his wounded comrades. Over the next five hours, Doss dragged wounded soldiers individually and lowered them over the ledge to the safety of their comrades below. All the time, he kept praying, “Lord, help me get one more.”

How many soldiers had Doss rescued? Division headquarters reported 155 men went up the escarpment, and only 55 returned from the hill on their own. Doss modestly stated that he saved 50 men.

Doss’ exploits were later featured in the 2016 feature film Hacksaw Ridge, directed by Mel Gibson.

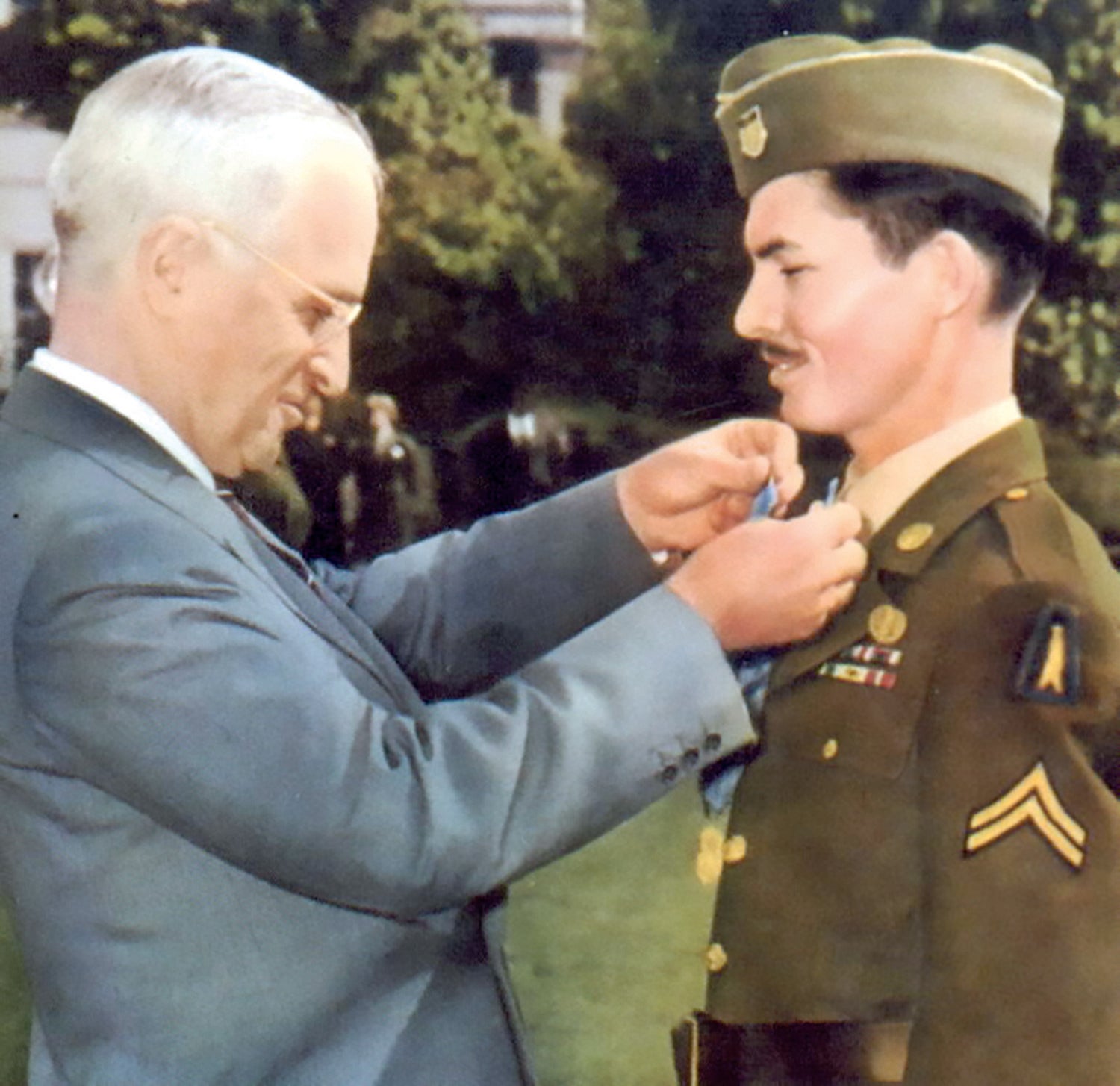

Doss repeated his heroics over the next two weeks before he was seriously wounded on May 21, 1945. Evacuated to the U.S., newly promoted Cpl. Doss received the Medal of Honor from President Harry Truman on Oct. 12, 1945. Doss died on March 23, 2006, and is buried in Chattanooga National Cemetery in Tennessee.

Doss remains the first conscientious objector to receive the nation’s highest award for valor in combat. Two decades later, Thomas Bennett and Joseph La Pointe Jr., also combat medics and conscientious objectors, followed in Doss’ footsteps during the Vietnam War.

Daniel Inouye

Half a world away, 2nd Lt. Daniel Inouye encountered a different type of prejudice than Doss. During World War II, Inouye fought two wars: one against the German army and a second against racial prejudice. In the process, Inouye demonstrated that heroism is colorblind, and courage is indifferent to racial identity.

Born in Honolulu on Sept. 7, 1924, to a second-generation Japanese American family, 17-year-old Daniel witnessed the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. As soon as he graduated from high school in 1942, he attempted to enlist in the Army, but the War Department classified Japanese Americans as “enemy aliens.” Not until those restrictions were lifted the following year could Inouye enlist.

Inouye joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit comprised almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry but commanded by Caucasian officers. Inouye progressed rapidly through the ranks, and in 1944, the 442nd deployed to Italy where Inouye earned his combat spurs in the fighting around Rome and central Italy.

Transferred to southern France to meet Germany’s late-winter offensive in the Vosges Mountains, Inouye cheated death when a German round hit him in the chest just above the heart. For his valor, Inouye received a battlefield commission to second lieutenant and a Bronze Star.

Inouye’s regiment returned to Italy in the spring of 1945. On April 21, Inouye led his platoon against a heavily defended ridge outside of San Terenzo. Unfazed by enemy fire, Inouye identified three enemy machine-gun positions. Crawling up a treacherous slope to within 5 yards of the nearest machine gun, he hurled two grenades and destroyed the enemy emplacement. He then neutralized the second position. Although seriously wounded by a sniper’s bullet, Inouye engaged more enemy positions until a grenade shattered his right arm.

Refusing evacuation, Inouye continued to direct his platoon until the ridge was safely in American hands. His wounds were considered life-threatening, but he survived. Inouye remained in the Army until 1947 when he was honorably discharged at the rank of captain.

After the war, Inouye returned to Hawaii and earned a college education through the GI Bill. In 1959, he was one of Hawaii’s first delegates to the U.S. House of Representatives. He later served in the U.S. Senate from 1962–2012, culminating in his position as president pro tempore of the Senate.

On June 21, 2000, in the name of Congress, President Bill Clinton bestowed the Medal of Honor on Inouye and 19 other members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Thirteen years later, President Barack Obama granted Inouye a posthumous award of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Inouye is buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

Roy Benavidez

Like Doss and Inouye, Staff Sgt. Roy Benavidez embarked on a journey from poverty and prejudice to receive the highest accolades of a grateful nation. Born on Aug. 5, 1935, near Cuero, Texas, Benavidez’s given name at birth was Raul Perez Benavidez. He changed “Raul” to “Roy” when he joined the Army in 1955.

The son of a Mexican farmer and a Yaqui Indian mother, Benavidez was a high school dropout and a troubled youth until he joined the Texas National Guard in 1952. Seven years later and after multiple overseas tours, Benavidez graduated from Airborne School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The school transformed Benavidez’s life. In his words, “Until I became Airborne, I had often allowed my temper and my insecurities to control the direction of my life.”

From 1959 to 1965, Benavidez served with the 82nd Airborne Division, and in 1965, he deployed to the Republic of Vietnam as an adviser to a South Vietnamese infantry unit. His tenure as an adviser was short-lived after he stepped on a land mine. Evacuated to the U.S., Benavidez was told he would never walk again.

Benavidez proved the doctors wrong, undertaking a severe physical regimen and cramming 18 months of healing and therapy into six months.

By 1966, he volunteered for Special Forces and received the coveted Green Beret the following year. In January 1968, Benavidez received orders to deploy to South Vietnam for his second tour.

On May 2, 1968, a 12-man Special Forces reconnaissance team was inserted by helicopters into a dense jungle to gather intelligence about confirmed large-scale enemy activity. Under heavy enemy fire, the team requested extraction. Three helicopters attempted to extract the team and were all shot down. Benavidez, who was monitoring the operation by radio, voluntarily boarded another aircraft to assist in another extraction attempt.

Unable to land at the designated pickup zone, he jumped from his aircraft and ran approximately 75 yards under withering small-arms fire to the crippled team. Despite multiple wounds in the abdomen and grenade fragments in his back, he repositioned the team members and directed their fire to facilitate the landing of an extraction aircraft. Despite his wounds, Benavidez gathered sensitive documents from the downed aircraft. Directing aerial and artillery fire against the enemy, Benavidez refused extraction until every surviving team member was safely aboard an aircraft.

By the time he returned to base camp, Benavidez was convinced he was dying. “My eyes were blinded. My jaws were broken, I had over thirty-seven puncture wounds. My intestines were exposed,” Benavidez wrote in his book with John Craig, Medal of Honor: One Man’s Journey From Poverty and Prejudice. For his actions on May 2, Benavidez received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Following a year of recovery, Benavidez returned to active duty. He retired as a master sergeant with a total disability in 1976 and returned to Texas. After years of bureaucratic machinations to gather pertinent information surrounding Benavidez’s heroic actions in the war, President Ronald Reagan presented Benavidez with the Medal of Honor on Feb. 24, 1981. Benavidez died in 1998 and is buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio.

A Higher Standard

Because the Medal of Honor is presented “in the name of the Congress of the United States,” it is frequently called the Congressional Medal of Honor. The terms are used interchangeably, but regardless of designation, the Medal of Honor remains the most prestigious and treasured of all decorations in the armed services.

Doss, Inouye and Benavidez are typical of the Medal of Honor recipients who have received the coveted award on behalf of their fallen comrades. May their shadows loom large and serve as a beacon to every soldier who wears the uniform of the U.S. Army.

* * *

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.