May 2021 Book Reviews

May 2021 Book Reviews

US Must Improve ‘Population-Centric’ Warfare

The American Way of Irregular War: An An.alytical Memoir. Charles Cleveland With Daniel Egel. Rand Corp. 276 pages. $40

By Lt. Col. Gregory Banner, U.S. Army retired

Retired Lt. Gen. Charles Cleveland had an eventful career as a Special Forces officer, both before and after the 9/11 attacks. His experiences included operations and assignments in Latin America, the Balkans, Southwest Asia and elsewhere, and he finished his service as commander of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command. In The American Way of Irregular War: An Analytical Memoir, co-authored with Daniel Egel, Cleveland uses his career and experiences to highlight recent successes and problems the U.S. has had conducting irregular war.

The history is interesting, but the real value of this book is in its attempt to move the Army and DoD to recognize the problems and do something to make the U.S. better in future counterinsurgency challenges.

A main purpose, therefore, is to pose difficult questions to the reader and consider critical components of unconventional operations. One of Cleveland’s repeated observations is that in conducting counterinsurgency campaigns specifically, and all “population-centric” operations in general, the U.S. has excelled at the tactical level but generally has failed at the operational and strategic levels. America has some great strengths. But there are some challenges where we cannot buy or shoot our way to success. Our performance in Vietnam and since has shown clearly how much we struggle with the prosecution of such conflicts.

The American Way of Irregular War does not spend a lot of time on the history of the Army’s Special Operations Command, but that history and the current nature of the organization are integral to Cleveland’s observations. Unfortunately, even with a national U.S. Special Operations Command, that organization has a clear focus on direct-action forces and missions. The organizations that know and practice population-centric missions are only truly represented at lower levels of the Army. These limitations have left DoD without a senior headquarters to either plan for or direct counterinsurgency campaigns, and the default has been to rely on conventional forces, headquarters and commanders at the time they are needed. This has played out over and over with the same results and for the same reasons.

History has shown that we have not systemically or doctrinally learned from our mistakes and struggles. It took direction by Congress to push major changes and create a U.S. Special Operations Command. Cleveland’s conclusions are that it will take the same external direction to address weaknesses in conducting population-centric campaigns.

With the decrease of active operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S., like after Vietnam, looks to return to conventional operations mixed with surgical counterterrorism strikes, with the hope of not being dragged into a large counterinsurgency campaign again. That hope is not realistic and does a disservice to tactical-level forces and headquarters, which are thrown into the breach to do the best they can, as well as to senior conventional leadership, which does not have the background to deal effectively with this most complex of challenges. Even where our involvement does not rise to the level of full-on combat operations, population-centric challenges are the norm around the world.

A realistic appraisal of our history concerning such things over the past 60 years will confirm that we just do not have it figured out. By raising these issues, Cleveland has tried to keep the discussion and topic alive. If anything, this work is too polite in calling out the national establishment to address these topics, as they will not go away and must be resolved for our Army and our nation.

The American Way of Irregular War is also available as a free download at www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA301-1.html.

Lt. Col. Gregory Banner, U.S. Army retired, was an infantry and Special Forces officer. He served in three Special Forces Groups, had a secondary specialty in civil affairs and served in a variety of special operations assignments, including a combat tour as a district team chief in a military advisory group.

* * *

The Personal Account of a WWII Tanker

1,271 Days a Soldier: The Diaries and Letters of Colonel H.E. Gardiner as an Armor Officer in World War II. Edited by Dominic Caraccilo. University of North Georgia University Press (An AUSA Title). 336 pages. $24.99

By Col. Kevin Farrell, U.S. Army retired

Memoirs from World War II have been a popular genre since the end of the war itself. That popularity remains to the present day. Whether they are the memoirs of senior officers such as Gen. George Patton Jr. (War as I Knew It) or Gen. Douglas MacArthur (Reminiscences) or accounts from lower-ranking soldiers such as Maj. Audie Murphy (To Hell and Back) or Maj. Dick Winters (Beyond Band of Brothers), the reading public has embraced first-person accounts, typically to try to understand the war experience.

Dominic Caraccilo has a new work that sheds light on armored combat and duty at the tactical level during World War II. While the majority of memoirs tend to be from infantrymen, this latest addition presents the point of view of a category of soldier often overlooked: the tanker and his life—to include combat—in tank battalions.

However, 1,271 Days a Soldier: The Diaries and Letters of Colonel H.E. Gardiner as an Armor Officer in World War II is not a wartime memoir, and readers should expect what the title of the book says it is: Gardiner’s personal diary and letters. For those interested in understanding the development of the U.S. Army’s armored doctrine, armored warfare overall, and an unvarnished account of what armored combat looked like in North Africa and Italy, this book is essential reading.

The breadth of encounters with famous individuals and battles is extraordinary for one man. Gardiner took part in the famed Louisiana Maneuvers in the fall of 1941, met the first Black general officer, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Davis Sr., met the future hero of the Buna campaign, Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, while he was the superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and also met Capt. William Orlando Darby, future commander of the U.S. Army’s 1st Ranger Battalion, in Northern Ireland. These encounters are just a prelude.

Gardiner was a witness to and participant in the first major combat in concert with European Allies, the Tunisian campaign of November 1942, including the disastrous American defeat at Kassarine Pass. His detailed accounts of the North African campaign are especially interesting, including encountering the much-feared German .88 mm gun, the most effective anti-tank gun of World War II.

The tone throughout is understated. Gardiner saw extensive combat as a squadron commander, was wounded and earned a Distinguished Service Cross, but there is never a hint of self-aggrandizement, exaggeration or self-pity. Fortunately, Gardiner possessed a dry wit, and humorous episodes lighten the reading.

The second half of the book is dedicated to Gardiner’s experiences in Italy from November 1943 to May 1945. Gardiner takes part in many of the more famous episodes of the Italian Theater, to include the landings at Anzio, the stalemate at Monte Cassino and the concluding battles in the Po River Valley at the end of the war.

Caraccilo’s insertion of numerous footnotes and summations is useful in providing historical context to the events Gardiner discussed in his diary entries and letters. Divided into three sections with photographs, maps and a bibliography, 1,271 Days a Soldier is appropriate for anyone with an interest in the history of the U.S. Army in North Africa and Italy during World War II, especially armored combat.

Col. Kevin Farrell, U.S. Army retired, is the former chief of military history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York. He commanded a combined arms battalion in Iraq. His most recent book is The Military and the Monarchy: The Case and Career of the Duke of Cambridge in an Age of Reform. He has a doctorate in history from Columbia University, New York.

* * *

Distant Battleground Proves Hard to Tame

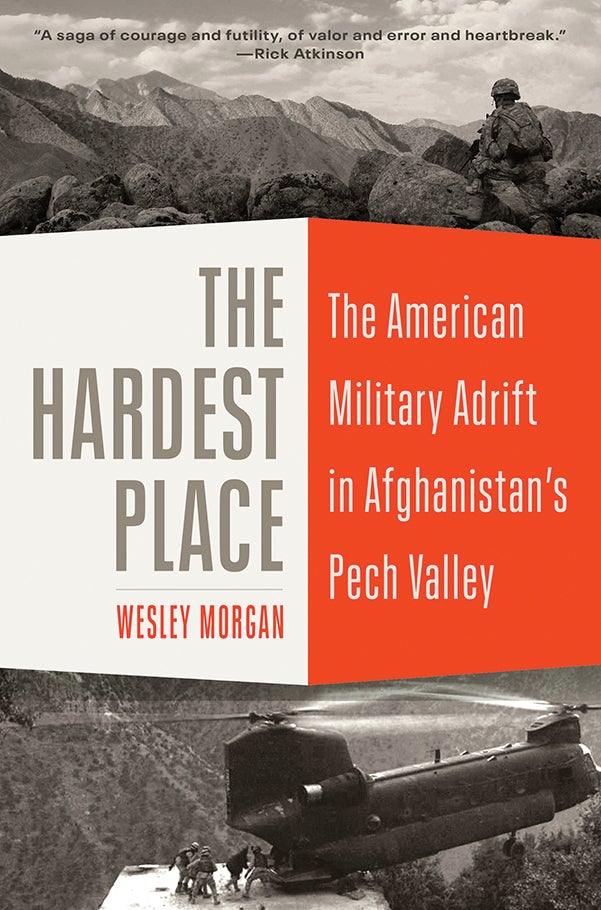

The Hardest Place: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley. Wesley Morgan. Random House. 672 pages. $35

By Lt. Col. Mark Reardon, U.S. Army retired

A new account of Operation Enduring Freedom is now available with the publication of The Hardest Place: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley. Although the subtitle might not instantly register, the Pech Valley and its environs have been featured in films such as Lone Survivor and The Outpost, documentaries like Restrepo and Korengal, and a number of books to include Ronald Fry’s Hammerhead Six and Sebastian Junger’s War.

Journalist Wesley Morgan’s contribution, however, differs in that he provides a full account from start to finish, from both the Afghan and American perspectives, while introducing personalities, technology, doctrine and organizations not previously covered in detail.

American special operators, armed with imprecise information collected by intelligence agencies struggling to adapt to a new world order and guided by Predator drones unable to distinguish a tall man from a normal-sized man surrounded by children, entered the Pech in 2002 searching for Osama bin Laden. The region’s inhabitants neither aided nor opposed the newcomers, remaining neutral until a series of mistaken strikes built up resentment over several years.

That shift took place as Afghanistan evolved from America’s strategic centerpiece to a sideshow following the invasion of Iraq. With special operators in high demand elsewhere, conventional infantry deploying to the Pech faced an organized popular movement determined to rid their valley of foreign troops. Members of the Taliban also gravitated into the Pech, seeking to establish themselves in a region where they never enjoyed much popular support.

The Americans, eager to utilize newly published counterinsurgency doctrine calling for the separation of the population from insurgents, established outposts near key villages. The outposts served as magnets for the valley people’s frustrations rather than beacons of stability. Making do with inadequate resources, soldiers from the most technologically advanced military on the globe endured daily mortar and rocket bombardments while hunkered inside sandbagged fortresses. Over time, al-Qaida operatives joined with the Taliban and the Pech’s inhabitants in their fight against U.S. forces. The Americans stubbornly defended the outposts, while mounting their own offensives into the mountains, until the Obama administration’s decision to wind down the conflict in Afghanistan.

The infantryman’s positional war in the Pech had ended, somewhat ironically, as the U.S. Army began to gain a belated appreciation of the region and its people. Abandoning permanent bases did not prevent the Americans from returning to deliver blows against their enemies, but the results proved both transitory and costly.

The lengthy struggle against the Americans, it appeared, resulted in the valley’s residents trading one group of outsiders for another. Not only did al-Qaida seek to maintain its foothold, but fighters from the Islamic State group and Syria appeared in the Pech. Determined to prevent foreign extremists from establishing terrorist sanctuaries in eastern Afghanistan, U.S. special operators and drones put the knowledge gained at great cost over an eight-year period to good use. That fight, albeit with more Afghan and less American involvement, continues today.

In an effort to capture the most dramatic elements of the story of the Pech Valley, Morgan adopts a bottom-up approach. As a result, he introduces broad-brush issues such as the unappreciated contradictions of population-centric counterinsurgency, as well as the tactical impact of the military’s rotation policies and the cultural differences between special operations forces and conventional infantry, without analyzing their impact on events.

To be fair, each of those topics warrants greater attention than the author can reasonably provide. Aside from that quibble, The Hardest Place serves as an adequate placeholder for the yet-to-be written official accounting of events in the Pech.

Lt. Col. Mark Reardon, U.S. Army retired, transitioned from armor officer to professional historian after 26 years of military service. He is the author of Victory at Mortain: Stopping Hitler’s Counteroffensive and several other books. His upcoming publications include a history of the post-Saddam Iraqi army and a two-volume account of Operation Enduring Freedom.

* * *

Paralyzed Vets Inspire Better Life at Home

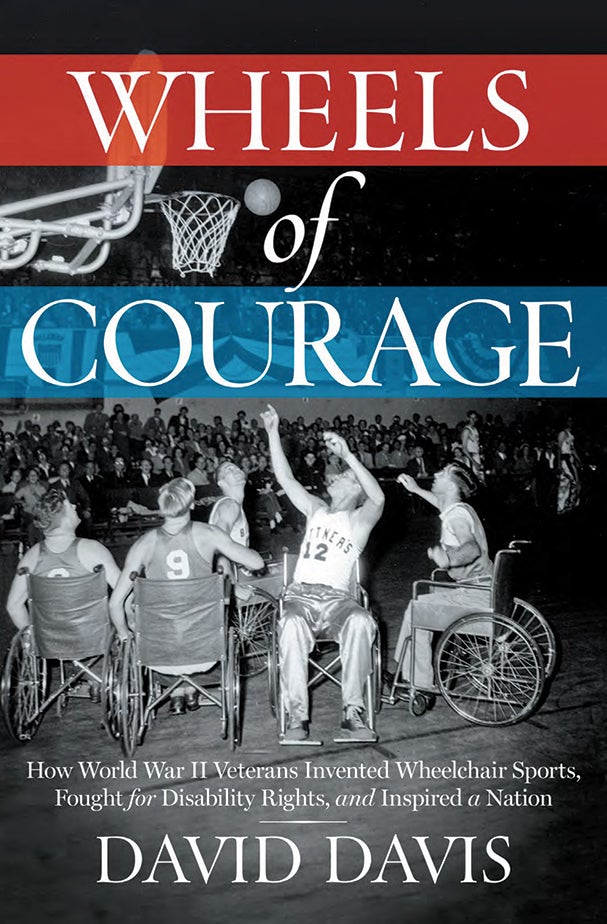

Wheels of Courage: How World War II Veterans Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation. David Davis. Center Street Publishers. 400 pages. $28

By Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Stories of “the greatest generation” have deservedly been commonplace in the last quarter-century. In Wheels of Courage: How World War II Veterans Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation, author David Davis narrates the inspiring story of one part of that generation that has been too often overlooked: veterans who were paralyzed during World War II. Davis also spotlights the doctors and physical therapists who treated those vets, as well as the coaches who motivated them through sports.

Trained as a journalist, Davis has documented the culture of sports for nearly three decades. His columns have appeared in Sports Illustrated, Smithsonian Magazine, The New York Times, and other leading newspapers and journals.

Davis begins his story with an exhibition basketball game at New York’s Madison Square Garden, the mecca of basketball, on March 10, 1948. Before the professional teams took the floor, the crowd was treated to an exhibition game between two teams of World War II veterans. What made this game so unique was the players were paralyzed from the waist down from injuries they suffered during the war.

To set the stage for the Madison Square Garden game, Davis focuses on three veterans who helped popularize wheelchair sports: Gene Fesenmeyer, Johnny Winterholler and Stan Den Adel. All three survived the battlefield, but their private wars to get to this game were just as arduous.

Den Adel’s story is particularly compelling. A 1943 Army draftee, he participated in the Army Specialized Training Program before the War Department abandoned the program in 1944. Deploying to Europe with the 11th Armored Division, Den Adel served in the Battle of the Bulge and was seriously wounded only a week before the European war ended, leaving him permanently disabled. He was one of the approximately 2,500 U.S. servicemen who returned from the war with spinal cord injuries.

During his recovery, Den Adel met Dr. Ernest Hermann Bors, whom the Veterans Administration (VA) had appointed to oversee the nation’s first spinal cord injury ward at Birmingham General Hospital in Van Nuys, California. A year after V-E Day, Den Adel met Bob Rynearson, the assistant athletic director at Birmingham, who soon organized a recreational basketball league for the patients to assist in the rehabilitative process. Players used the newly invented collapsible wheelchair. Rynearson developed a set of 10 rules to govern the new league, and he relinquished recruiting chores to Den Adel.

Fesenmeyer’s and Winterholler’s saga of recovery mirrored Den Adel’s. Together the duo played on the Rolling Devils team that conducted two road trips in the spring of 1947, a journey that introduced wheelchair sports to a national audience.

Soon, the emerging phenomenon of wheelchair basketball spread throughout the VA, and additional teams such as the Flying Wheels, the Bronx Rollers and the Hines Gizz Kids were quickly assembled by the staff at rehabilitative centers around the country.

Off the court, these same disabled veterans proved instrumental in creating the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), a nonprofit organization formed to address the specific concerns of paralyzed veterans. In 1971, Congress granted the PVA a charter, a rare distinction for a nonprofit organization.

The efficacy of rehabilitation surrounding athletic events expanded from the initial works of Bors, Rynearson and a host of other allies to the modern Paralympics, the National Wheelchair Basketball Tournament and the Invictus Games. Decades after the war, paralyzed veterans from the greatest conflict in world history emerged as the most ardent supporters of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 signed into law by President George H.W. Bush.

Wheels of Courage illustrates conclusively that with proper care and rehabilitation, disabled veterans not only can make a valuable contribution to society, but they also serve as a model of inspirational heroism and courage that transcends generations. The players and coaches; the doctors, staff and therapists of the VA; and the early advocates for paralyzed veterans all demonstrated that “what mattered most wasn’t disability, but ability.”

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.