May 2019 Book Reviews

May 2019 Book Reviews

Special Operations Soldiers Lead the Way

Run to the Sound of the Guns: The True Story of an American Ranger at War in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nicholas Moore and Mir Bahmanyar. Osprey Publishing. 303 pages. $30

By Charles W. Sasser

In the tradition of soldier classics like All Quiet on the Western Front, Nicholas Moore and his co-author Mir Bahmanyar unfold Moore’s raw war story of a decade of over 1,000 special operations missions and a dozen deployments into the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan. Run to the Sound of the Guns is the engrossing drama of Army Rangers—the training, the fighting, the brotherhood of young men in combat, of high adventure and darkest tragedy.

Enlisting in the Army directly out of high school, Moore was still in Ranger training on 9/11. Less than a year later, he deployed with his battalion to Afghanistan and Operation Enduring Freedom. Rangers routinely rotated in and out of war zones in a pattern of 90 or 120 days in country and six months of uptraining and refitting stateside.

Afghanistan was, Moore recalls, the most boring place, without an enemy in sight. That couldn’t be said of Iraq in 2003 and the campaign against Saddam Hussein. During the day, Mosul, Baghdad and other Iraqi cities were chaotic and dusty with traffic. The cockroaches came out after dark. Rangers were running and gunning five or six times a night, targeting wanted insurgents, taking them alive when possible to exploit their intel for future operations. It was a lot like a deadly game of cops and robbers.

In 2003, Moore’s unit assisted Navy SEALs in rescuing Pfc. Jessica Lynch from a hospital in Nasiriyah, Iraq, where she was being held captive. Two years later, again in Afghanistan, Moore and other Rangers recovered Petty Officer 2nd Class Marcus Luttrell, the lone survivor of a SEAL team whose helicopter either crashed or was shot down.

IEDs became a constant threat throughout the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq. Enemy contacts were more frequent. The largest single loss of American life in Afghanistan occurred in the Tangi Valley when Taliban armed with a rocket-propelled grenade shot down an American chopper loaded with SEALs. All 38 aboard perished. American casualties were mounting throughout the theaters. Moore lost friends.

Rangers increasingly had to make split-second judgments. A wrong call meant possible criminal charges—or death. Moore and his team were clearing a room when an Iraqi man pulled a woman tight in an unprecedented show of affection. Moore shot him after he refused to comply with Arabic instructions to put up his hands, and his teammates fired when she then tried to reach under her companion’s body. The man had been trying to conceal a suicide vest with 7 pounds of Semtex that would have killed them all.

On Moore’s last combat deployment to Afghanistan in 2011, he and a team from his platoon tracked a target to a village compound and ran straight into an ambush.

“The three-round burst fired from an AK inside the compound slams hard into me—punches me back, spins me around, thumps me off balance like a marionette manipulated by invisible strings,” he writes. “My leg feels like it’s been hit with a sledgehammer. My head is a mess. My wife is gonna kill me.”

After more than 10 years of continuously running to the sound of guns, this was the only time Moore received a Purple Heart. He was subsequently medically discharged from the Army due to his wounds.

But for Moore, Rangers will always lead the way.

Charles W. Sasser served for 29 years in the military, including 13 years as an active-duty and Reserve member of U.S. Army Special Forces and four years as an active-duty Navy journalist. He deployed in support of Operation Desert Storm.

* * *

Take a Fresh Look at the Longest Day

Sand and Steel: The D-Day Invasions and the Liberation of France. Peter Caddick-Adams. Oxford University Press. 928 pages. $34.95

By Col. Cole C. Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

The 75th anniversary of D-Day, June 6, 1944, will likely herald a number of excellent histories commemorating the events of what is arguably the most significant day in Western civilization during the 20th century. Foremost of these from the other side of the Atlantic is Peter Caddick-Adams’ Sand and Steel.

Caddick-Adams is a lecturer in military history at the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom. An accomplished historian, he is the author of Monte Cassino: Ten Armies in Hell and Snow and Steel: The Battle of the Bulge, 1944–45. In writing Sand and Steel, Caddick-Adams acknowledges his debt to Cornelius Ryan, the author of The Longest Day: The Classic Epic of D-Day, June 6, 1944, as the individual most responsible for beginning the “whole D-Day commemorative business.”

Caddick-Adams is at his best describing the lesser-known aspects of D-Day such as the Allied buildup, the role of deception, and logistics. He opines that the Allied deception plan named Operation Fortitude, with its emphasis on fictional armies, double agents and deceptive radio traffic, stood in sharp contrast to Germany’s “stovepiping” of intelligence.

Challenging the conventions of history, Caddick-Adams also posits that the German meteorologists were equally proficient as those in the Allied camp, but Allied weather mapping was superior, being drawn from more sources. Fortunately for the Allied planners, the German High Command failed to coordinate forecasting from the Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine (navy) and Heer (army).

The heart and soul of Sand and Steel, however, is the drama played out on the five beaches, code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. Caddick-Adams combines official unit histories and personal narratives to compare the American amphibious landings at Utah and Omaha. He cites Maj. Gen. Thomas Handy, who he calls the director of operations in the War Plans Division, who reported that “we all thought Utah was going to be more of a problem than Omaha.” But the performance of the untested 4th Infantry Division under Brig. Gen. Teddy Roosevelt Jr.’s inspired leadership incurred far fewer casualties than the 1st Infantry Division that landed at Omaha.

Caddick-Adams states that most military historians are incorrect when they assess that the German 352nd Infantry Division stationed behind the American beaches was a crack unit with a strength of 13,000. The German division was formed only in September 1943 from divisions that had been decimated on the Eastern Front and, in the words of one of its soldiers, was “a thrown together mob.” Approximately 50 percent of the officers lacked combat experience and the NCO ranks were short by nearly a third.

Caddick-Adams also takes umbrage with the interpretation of the U.S. Army’s official narrative, Cross Channel Attack, and Ryan’s The Longest Day, on the Ranger assault on Pointe du Hoc. Ryan classified the action as heroic but futile because the cliffside gun emplacements were empty, while the official account recognized that the guns had been moved inland, but minimized the effort to destroy them. The salient point, Caddick-Adams notes, is that “the cannon, wherever they might have been, were useable, supported by trained artillerymen, well-stocked with ammunition, and thus posed a serious threat to the invasion.”

Why have so many historians been misled in their interpretations of D-Day? Caddick-Adams contends that accounts of the amphibious landings, particularly at Omaha, “tend to be land-centric—for this is where most of the tales of derring-do came from. Yet, oft-overlooked, is the fact that the key enablers [of American success at Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc] were the five-inch guns of the fleet destroyers.”

Though his examination of the British/Commonwealth amphibious landings lacks the detailed analysis of the American zone, Caddick-Adams has made a monumental contribution to our understanding of D-Day. To stress the importance of Allied solidarity in the current political environment, the author reminds us that Sand and Steel is not a flag-waving exercise to tout the importance of any one country’s efforts over those of the other Western powers. On that day, in the words of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, “there was only one nation—Allied.”

Col. Cole C. Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate from Ohio State University.

* * *

Historical Tome Covers War From All Sides

Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945–1975. Max Hastings. HarperCollins. 896 pages. $37.50

By Lt. Gen. Theodore G. Stroup, U.S. Army retired

Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945–1975 is a good read for those interested in the history of that country from the end of World War II and the Japanese withdrawal to the closing of American and allied participation in the Vietnam War in 1975. Interspersed in those years, the involvement of France, from national and local politics to combat on the ground, gets detailed coverage, as does the burgeoning independence movements in the north and the south of the country.

The book can also be a tough read for those who have read other Vietnam accounts solely from the American perspective. It might be even tougher for Vietnam veterans, who might reflect on their time in country and disagree with the author’s accounting and judging of events. Further, author Max Hastings overlooks the full scope of the support side of the militaries involved, skimping on details of logistics, transport and medical efforts—not to mention the North’s impressive operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Hastings, however, has the advantage that he was on the ground during the war, observing from the American and allied sides. Building on this firsthand knowledge, he brings to bear detailed research from documents and interviews with participants from all sides—Vietnamese, French, Viet Minh, Viet Cong, American, Australian and New Zealander, South Korean, Chinese and Russian—to provide a thorough account of all levels of political and military actions during 30 years of conflict. It is evident from his detailed notes and large accompanying bibliography that he put a great deal of time into investigation and research for this work.

The results of that detailed research and reporting leave no side—no nation and no participating military or government—unscathed from Hastings’ candid observations and opinions.

The vignettes of citizens and soldiers on all sides are one of the elements I liked about the book. They humanized the viciousness and tragedy of combatants and citizens in ways seldom encountered in a historical work of a wartime period. Readers of Hastings’ earlier histories of conflict, such as his works on World War II, will find his technique of combining these incisive individual stories and experiences with big-picture focus enhances the scope and breadth of the story.

One example is a section devoted to Australian and New Zealander participation in the war. It covers the efforts of our allies on the battlefields, the experiences of their veterans returning home after tour completions, and offers parallel incidences of news reporting from their own national press coverage. This is a big plus as those countries are often overlooked in the U.S.

The author rightfully exposes the brutality and viciousness of the North during and after the war concludes. This series of acts encompasses not only combat atrocities, but the viciousness and “cleansing” after the final episodes of communist takeover of the country. Most of these actions never surfaced during wartime reporting or the press coverage of the North and South after the fighting ended.

Weighing in at almost 900 pages, this work is not for the casual reader. For some veterans, it will open and close their understanding of why they went to war and why they left. For others, there will be some bitterness in the accounting of battlefield and politics. And for those reflecting on today’s 17-plus years in Afghanistan, preceded by Iraq, the book raises the same questions: How did we get there, and how will it end?

Lt. Gen. Theodore G. Stroup, U.S. Army retired, served in the Army for 34 years, including time in Vietnam as a company commander. His last assignment was as the Army’s deputy chief of staff for personnel. Upon retirement, he served as vice president for Education at the Association of the U.S. Army, and he is now a senior fellow of AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare.

* * *

Understanding America’s Most Revered Honor

The Medal of Honor: The Evolution of America’s Highest Military Decoration. Dwight S. Mears. University Press of Kansas. 328 pages. $34.95

By Col. Steve Patarcity, U.S. Army Reserve retired

The Medal of Honor is America’s highest military decoration for valor. It has a legendary and almost mystical quality among members of the armed forces, who know that its price is all too often the highest that can be paid. The general perception of the Medal of Honor is that it is presented for heroic acts above and beyond what could be expected—i.e., “beyond the call of duty”—and many assume it has always been that way.

To the contrary, as Dwight S. Mears shows in The Medal of Honor: The Evolution of America’s Highest Military Decoration, the Medal of Honor in its current form is different from its historical antecedent of the Civil War. The validation processes for the medal have varied greatly over the past 150-plus years; during one period, there were even three versions with different criteria, including separate combat and noncombat versions for the Navy.

At times there have been conflicting legislation and policies governing the presentation of the decoration, and there are many examples of acts performed by Americans that deserved recognition but sadly were overlooked due to prejudices and prevalent beliefs. Mears’ exhaustive research into the medal, to my knowledge the first complete and inclusive look into its history, clearly and concisely shows how the medal has changed and evolved beyond its original inception and how it did not achieve relative standardization until the Vietnam War.

Mears most effectively charts not only the evolution of the medal but also shows how policy and legislation changed and modified it before and during past and current conflicts, including relative periods of peace and stability in between. He accomplishes this task by dividing his book into two distinct sections, the first dealing with the legal and policy history behind the medal and the second covering legislative, administrative and judicial actions to make exceptions to the rules.

Mears’ documentation on his subject can only be classified as superbly crafted. His scholarship rests firmly on several factors: his meticulous research, his objectivity and fairness, and his straightforward presentation of his material. There have been books focusing on service members who have received the medal; readers expecting such a collection of stories of unbelievable courage and self-sacrifice may be a bit disappointed. Mears instead focuses on the fascinating, at times rocky, history of the Medal of Honor on its way to the medal it is today.

I most highly and unreservedly recommend this book, both as an excellent resource for any scholar to research and understand America’s most revered honor that can be conveyed on its warriors and as an in-depth study of how the decoration evolved over time.

Col. Steve Patarcity, U.S. Army Reserve retired, is a civilian strategic planner on the staff of the Office of the Chief of Army Reserve at the Pentagon. He retired in 2010 after 33 years of service in the active Army and Army Reserve, which included military police and armor assignments in the U.S., Kuwait and Iraq.

* * *

Granddaughter Battles to Change Arlington Cemetery Law

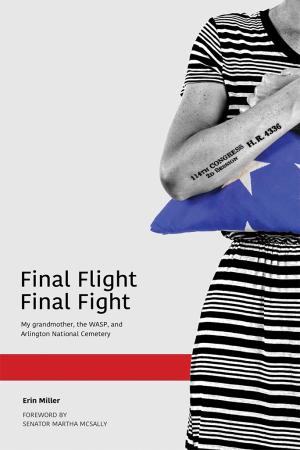

Final Flight Final Fight: My Grandmother, the WASP, and Arlington National Cemetery. Erin Miller. 4336 Press. 350 pages. $25

By Maj. Crispin J. Burke

As the U.S. prepared to enter World War II, the fledgling U.S. Army Air Corps needed every aviator it could find. With pilots in short supply, the government established pilot training programs. In the process, officials sought out anyone who could qualify—man or woman.

Not long after Pearl Harbor, the government established a special program for female aviators known as the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Throughout the war, WASP served as flight instructors, ferried aircraft to combat theaters and even transported parts for the atomic bomb.

Over the course of the war, over 1,000 women qualified for the WASP program, with 38 losing their lives in accidents. Although WASP took part in military training, wore uniforms and even saluted officers, they weren’t officially considered part of the military. Those who were killed were sent home in pine boxes at their families’ expense. They weren’t even authorized to have an American flag draped over their coffins.

Decades later, former WASP Elaine “Gammy” Harmon succumbed to cancer at age 95. Her handwritten instructions to her family were, “I would like to be buried in Arlington Cemetery. Proof of my veteran status is necessary.” What follows is the subject of the book Final Flight Final Fight: My Grandmother, the WASP, and Arlington National Cemetery, written by Harmon’s granddaughter, Erin Miller.

Miller and her family soon discovered they needed special, case-by-case permission to place Harmon’s ashes in Arlington National Cemetery because DoD didn’t technically consider WASP personnel to be service members. As Harmon’s ashes sat in a plastic bag in a closet, Miller realized the only way to allow her grandmother—and all the WASP—to be inurned in Arlington Cemetery was to change the law.

It’s not easy to turn the legislative process into an interesting story, but Miller manages to do so through the fascinating characters she introduces both in the halls of Congress and within her own family. Though Miller has praise for representatives on both sides of the aisle, then-Rep. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., a former A-10 pilot, emerges as a hero by sponsoring House Resolution 4336, which eventually allows every member of the WASP program to be laid to rest at Arlington. At a time when it seems Congress can’t get anything done, the bill manages to pass in near-record time. By the end of the book, Harmon is finally laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery in a ceremony featuring a flyover by vintage World War II planes.

Final Flight Final Fight is a fast, engaging read from a first-time author. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the early pioneers of aviation as well as anyone who wants to hear the story of a family coming together to fight a decades-long wrong.

Maj. Crispin J. Burke is an aviation officer who has served with the 82nd Airborne Division. He can be followed on Twitter at @CrispinBurke.