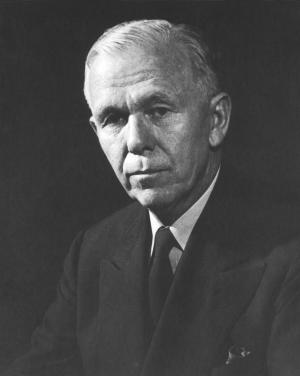

Although President Franklin Roosevelt was famous for letting members of his administration compete to get things done, Gen. George Marshall had his own way of deftly orchestrating major personalities—including the president himself—in assuring victory in World War II.

Marshall not only had to oversee and manage the global two-theater war against Germany and Japan, but he also constantly had to do battle over resources, strategies and priorities with Roosevelt, Congress, American industry CEOs, the U.S. Navy and the British high command, including Prime Minister Winston Churchill. He also had to assure that his key subordinate general officers—Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur, Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold and George Patton Jr.—were successful.

In his relationships, Marshall sought problem-solving outcomes; he would give general guidance and expect the other party to deliver results without coming back to him for decisions.

Some of Marshall’s most important relationships, which were instrumental in shaping the course of World War II, follow.

Roosevelt and Congress

From a national security standpoint, Roosevelt’s appointment of Marshall as chief of staff on Sept. 1, 1939, turned out to be the most important personnel selection of Roosevelt’s presidency, as he came to rely on Marshall to effectively conduct the global war effort and adroitly handle the Allies.

But there was a rocky start between the two men. At a well-attended meeting in the Oval Office on Nov. 14, 1938, Marshall, then deputy chief of staff of the Army, took issue with Roosevelt’s stated intent to immediately produce 10,000 planes at a cost of $500 million, then 20,000 planes per year after that, with many to be shipped to the U.K. and France. Marshall pointed out the flaws in that approach, which included no consideration of training a sufficient number of pilots and the critical need to also fund a buildup of the U.S. Army. The shocked attendees thought this spelled the end of Marshall’s career. However, 10 months later, Roosevelt appointed him chief of staff, precisely because he spoke his mind, among other reasons.

At the outset of Marshall’s appointment as chief of staff, Marshall persuaded Roosevelt to support his extensive mobilization plans for manpower and materiel, and secured congressional approval to finance this buildup, despite a powerful isolationist bloc in Congress and the country. Roosevelt (and later Harry Truman) astutely recognized that Marshall’s gravitas and sterling reputation with the public and with politicians of all stripes enabled him to push initiatives through a Republican congress that the president would not be able to do.

From 1942 on, Marshall had to juggle and reconcile Roosevelt’s changing military priorities, usually based on Churchill’s never-ending backdoor communications with the president. Per Roosevelt’s decision, as Army chief, Marshall was responsible for oversight of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. His influence on Capitol Hill assured funding support from members of Congress who did not have the proper clearances to be briefed on the project. While Roosevelt was expected to name Marshall as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, he ultimately concluded he couldn’t rely on any other officer to direct the global war effort—so Marshal’s protege Eisenhower got the job.

In order to maintain his apolitical, nonpartisan objectivity, Marshall was determined to avoid coming under Roosevelt’s well-known “spell.” So, he turned down invitations to join Roosevelt at Hyde Park, New York, and on the presidential yacht. Also, Roosevelt always called key figures by their first names, but when he first referred to Marshall as “George,” the general signaled his displeasure. After that, Roosevelt always addressed him as “Gen. Marshall.”

Winston Churchill

By early 1942, Churchill had come to realize that Marshall was the most influential figure of the Allied war commanders. Indeed, Marshall devised the structure of, and was the key driver in the deliberations of, the Combined Chiefs of Staff—a collaboration of the American and British chiefs of staff to develop and execute the Allied military conduct of the global war.

Contrary to British policy, practice and wishes, Marshall insisted on and ultimately secured Allied approval of Unity of Command—a concept and command structure under which a single supreme commander in each theater would be responsible for ground, air and naval forces and operations. He determined that Operation Overlord, the cross-English Channel invasion of France, was the best way to win the war in Europe with the fewest possible Allied casualties. Marshall then singlehandedly ensured that Overlord would go forward as planned despite Churchill’s continuing efforts to postpone or cancel it and shift invasion resources to the Mediterranean Theater and the Balkans.

He ultimately prevailed over Churchill, the British Imperial General Staff and senior British field commanders who had a different agenda and mindset with respect to global military strategy, the optimal way to invade the European Continent, the conduct of the multitheater war and the preservation of the British Empire at all costs. After the war, Churchill famously recognized Marshall as the “true organizer of victory.”

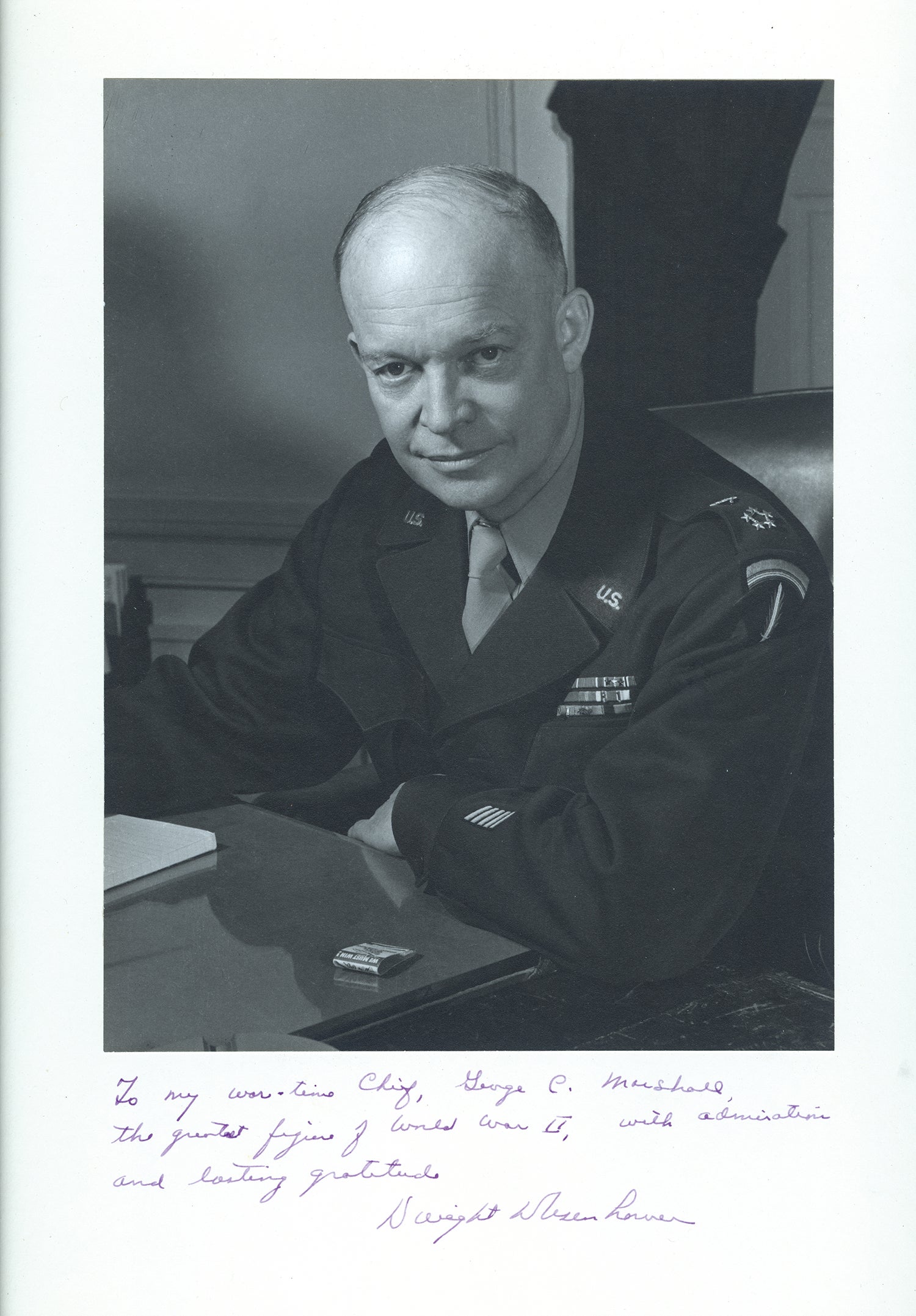

Gen. Dwight Eisenhower

After Pearl Harbor, Marshall brought Dwight Eisenhower, a newly minted one-star general, to Washington on his War Plans staff. He groomed Eisenhower for high command, promoting him to three stars within eight months and assigning him to Europe as commanding general of the U.S. European Theater of Operations. After Eisenhower became Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Marshall had to ensure his protege was successful. In this regard, he kept Eisenhower on a short leash—constantly providing back-channel guidance, bolstering his confidence, which flagged from time to time, and encouraging him not to go overboard in meeting British demands at the expense of U.S. strategies and interests.

With Roosevelt close to death in early April 1945, Marshall was the final arbiter in the strategic decision proposed by Eisenhower to forego a drive to Berlin in light of three principal factors: Soviet forces were already close to the German border; the Yalta agreements made it impractical; and it would have meant many more U.S. casualties, which were not necessary to win the war.

This meant the primary focus of the campaign was shifted from British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery to U.S. Gen. Omar Bradley, which did not please the British. Moreover, because he placed Eisenhower in a position to become the most famous face of victory in World War II, Marshall ultimately helped put Eisenhower into the Oval Office.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur

Marshall also played a key role in planning and prioritizing operations in the Pacific and European Theaters. This meant skillfully supporting MacArthur while keeping him under control. Marshall was widely recognized as the only general officer who could do so in light of MacArthur’s monumental ego and rogue operating style.

MacArthur was too self-centered to appreciate that Marshall was his best ally in Washington during the war. Without Marshall’s approval, MacArthur would never have been allowed to lead a second Pacific Theater thrust toward Japan, since the U.S. Navy vehemently opposed this two-pronged approach. Contrary to widespread belief, Marshall always backed MacArthur as best he could.

Following MacArthur’s arrival in Australia after his withdrawal from Corregidor, the Philippines, Marshall steered the effort to award MacArthur the Medal of Honor, and personally wrote the citation, principally to give the American people a hero to rally behind in those early dark days of the war.

One known instance when Marshall had to take issue with MacArthur was when Marshall reprimanded him in late 1944 for monopolizing cargo vessels, which were needed for operations in other theaters. Both Roosevelt and Truman were leery of MacArthur’s penchant for doing things his way and his well-known political ambitions, and relied on Marshall to keep him in line.

Gen. George Patton Jr.

Marshall regarded Patton as the Allies’ best fighting general, based on Marshall’s recognition of Patton’s unique armored force credentials and audacious offensive mindset. This perspective dated from World War I and was reinforced in the interwar years by Patton’s superior performances during military exercises.

After Marshall became chief of staff in fall 1939, he promoted Patton twice by spring 1941, to brigadier general and major general. But Marshall also realized that Patton could sometimes be a loose cannon and that he required careful monitoring. Despite Patton’s personality flaws, Marshall was instrumental in assuring he was able to make significant contributions to the war effort.

When Patton became embroiled in a series of embarrassing incidents in the summer of 1943 and the spring of 1944 that caused a tremendous backlash in Washington (soldier slappings and an inappropriate briefing to a women’s club), he left Patton’s fate up to Eisenhower. However, Marshall told Eisenhower that the key factor in his decision regarding Patton’s fate should be to not weaken Overlord’s combat capabilities. Eisenhower got the message and retained Patton in a key command role.

Thus, Marshall basically saved Patton’s career, enabling him to gain fame and glory as commander of Third U.S. Army.

Other Relationships

Although Fleet Adm. William Leahy, Roosevelt’s personal chief of staff, was nominally chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, all members—as well as those in the British high command—recognized and acknowledged Marshall was “first among equals” and the prime driver of the group.

Marshall’s close working relationship with the acerbic Fleet Adm. Ernest King, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and chief of naval operations, was crucial in orchestrating a balance in U.S. strategy between the European and Pacific Theaters. This close relationship also ensured mutual cooperation between MacArthur and Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, since the two-pronged thrust in the Pacific meant there was no primacy of command and control over military and naval operations in that theater.

Marshall provided key aircraft production, materiel, organizational and command support to U.S. Army Air Forces commander Gen. Arnold, enabling the underdeveloped air arm to rapidly grow and maximize the use of strategic and tactical air power, in many cases overriding the views of senior Army and Navy officers. This initiative turned out to be instrumental in winning the war. Marshall also insisted Arnold be a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

While Overlord was opposed by the British high command until late in the war, it was strongly supported by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin as providing an all-important second front in Europe. Stalin came to greatly admire Marshall’s strategic acumen and supreme generalship, and would put his arm around Marshall as a display of this admiration.

When Roosevelt died, Truman was quick to recognize that Marshall was the one indispensable man in closing the Allied victory. This confidence led Truman to later tap Marshall as secretary of state and then secretary of defense.

Through his foresight, brilliance, exacting standards, tenacity, integrity and the force of his personality, Marshall was able to master relationships with the other giant personalities of World War II in meeting countless challenges.