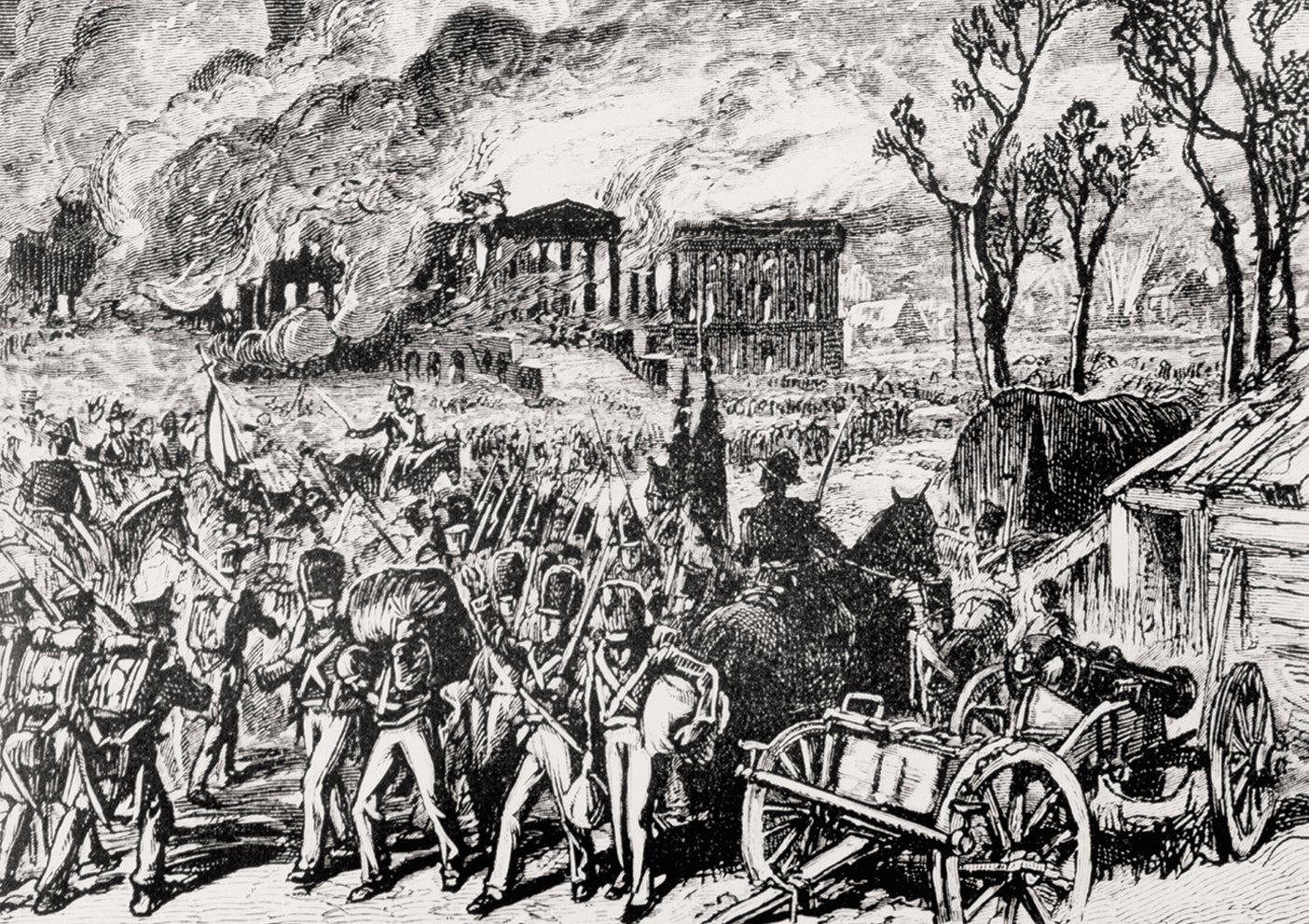

Many of us associate the War of 1812 with the heroic exploits of Andrew Jackson at New Orleans in 1815, and first lady Dolley Madison saving a portrait of George Washington as she fled the White House in 1814. Francis Scott Key’s poem, which 100 years later would become our national anthem, was inspired by the failed attempt of the British fleet to capture Fort McHenry at Baltimore in 1814. Former Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were still alive to witness the British burn Washington, D.C., to the ground.

A Regular Army of 35,000 augmented by tens of thousands more in militia forces took up the call to arms during the conflict, from June 1812 to February 1815. As in all wars, thousands of “little guys” fought for America—most of them now long forgotten.

One of them was Hiram Cronk. When Cronk died in 1905 at age 105, he was the last survivor of the War of 1812. “He saw coal oil supersede the candle, only to be passed in turn by gas and electricity” during his lifetime, according to an article in The Minneapolis Journal, and “saw his country pass through its various baptisms of blood” including not only the War of 1812 but also the Texas and California revolutions, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War and the Spanish-American War.

Enlisted at 13

Hiram Cronk was born in 1800 in Frankfort, N.Y. The U.S. Constitution was only 12 years old, and there were only 16 states. John Adams was America’s second president. When Hiram was 3, then-President Jefferson engineered the purchase of the Louisiana Territory.

Hiram joined the Army at age 14, enlisting with his father and two brothers. His father, James, had previously served in the Revolutionary War; his Uncle Jacob had been killed at the Battle of Bennington in 1777 at Walloomsac, N.Y.

Hiram’s actual military service lasted about 100 days at Sackets Harbor, N.Y. According to an account in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Daily Democrat, the teenager was of such “extreme frailty” that he was “the butt of many jokes.” His fellow soldiers claimed if he was exhausted or wounded, “his father could pack him away in his coat pocket.” However, “in one skirmish … he behaved in such a soldierly manner” that his captain, Edward Fuller of the 157th Infantry, commented that if he “had a company of men as full as nerve as young Hi Cronk,” he would have invaded Canada and beat the British on their home turf.

After he was discharged, Hiram stayed overnight at Watertown, N.Y., before going home. He heard “the sound of cannonading” at Sackets Harbor on Lake Ontario, where a British warship was bombarding the fortifications. Within a few weeks he was back in the ranks as a private, assisting in the construction of log barracks along the shore. He was honorably discharged from the Army in November 1814.

After his service, Cronk made his livelihood as a shoemaker, spending his working career around Watertown. In 1825, he married Mary Thornton. The couple had 10 children; seven survived to adulthood. One son was killed during the Civil War at the Battle of Shiloh. When Mary died in 1885, the couple had been married for 60 years.

According to the Daily Capital Journal of Salem, Ore., Cronk lived on a 120-acre farm. Eighteen years before his death, he moved in with his 70-year-old daughter, Sarah, and son-in-law. Sarah arranged for her father to receive a monthly pension of $8, which was raised to $12 in 1886.

After Cronk turned 100, a special act of Congress raised his monthly pension to $25. Three years later, the New York State Legislature voted to award him a monthly pension of $72.

Tobacco, Wine and Milk

Various newspaper articles described Cronk’s sprightly demeanor, good hearing and sight. When Cronk was about 103, he was interviewed by the New-York Tribune. The newspaper reported that the centenarian and veteran “keeps up his strength on tobacco, wine and milk. … He has used tobacco from boyhood [and] consumes a gallon of wine each day.” (A later report said Cronk consumed a gallon of wine biweekly.)

Cronk also indulged himself in Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey, saying he “took a dessert spoonful … three times a day” with meals and before bedtime. This testimonial was included in a Duffy’s ad promoting the medical and health benefits of the whiskey, which allowed the centenarian “to be out every day” and “take quite extended tramps.”

After Cronk died in May 1905, three ministers performed the funeral in his house. His body then was transported by train to New York City, where it laid in state at City Hall before burial in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery.

The funeral procession included a horse cavalry, a Rough Riders brigade, uniformed Civil War veterans and a marching band. A film reel of the procession to City Hall has been posted on YouTube under the title “Funeral of Hiram Cronk 1905.”