January 2021 Book Reviews

January 2021 Book Reviews

McMaster on National Security, Not Politics

Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World. H.R. McMaster. HarperCollins Publishers. 560 pages. $35

By Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Former U.S. national security advisor and retired Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster delivers a candid assessment of American national security policy over the past two decades in Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World.

Despite his stint in the White House under a most controversial president, Donald Trump, McMaster views himself as “apolitical” in the tradition of Gen. George Marshall, Army chief of staff under Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman during World War II.

This is McMaster’s second book. As with Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies that Led to Vietnam, McMaster applies the military historian’s eye to evaluate issues of national security confronting the United States. By his own admission, Battlegrounds is not the book most people wanted him to write. Refusing to dabble in partisan politics or to confirm or deny personal opinions of Trump, he seeks to improve understanding of the most significant domestic and international challenges this country faces in the 21st century.

McMaster divides his seminal work into eight parts, seven of which address concerns in distinct geographic regions. The final section calls for a reengagement of the U.S. to address threats posed by both governmental and nongovernmental entities, including Russia, China, South Asia, the Middle East, Iran and North Korea.

The beauty of Battlegrounds is that McMaster not only identifies the threats but also provides the most effective way to combat these dangers. With respect to Russia, McMaster views the country’s appearance of strength as belying significant weaknesses in its economy, demographics, public health and social services.

To parry Russian President Vladimir Putin’s playbook, McMaster advocates stronger relations among the Western democracies and the avoidance of “strategic narcissism,” the tendency to view the world only in relation to the U.S. and to assume that future events depend primarily on U.S. decisions or plans.

A far greater danger to the U.S., in McMaster’s estimation, is that posed by Xi Jinping’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP), based on the scale of the challenge and the party’s obsession with control. In one of his first meetings with the White House’s National Security Council, McMaster directed the team to initiate an assessment of China policy with an emphasis on strategic empathy to obtain “a better understanding of the motivations, emotions, cultural biases, and aspirations that drive and constrain the CCP’s actions.”

This reappraisal led to a series of new assumptions, the most significant being that the CCP’s obsession with control prevents China from liberalizing its economy or form of government. Nor will China play by international rules, cease its economic aggression or halt its attempts to establish control of strategic locations and infrastructure. Competing effectively with China diplomatically, economically and militarily should be understood as an effective way to avoid confrontation with the CCP, McMaster writes.

McMaster applies a similar formula to the dangers emanating from the Middle East and the terrorist states of North Korea and Iran. Climate change, internet security, technological innovation and a lack of “strategic empathy” also pose significant challenges to U.S. prosperity.

Will Battlegrounds contribute to the strength of our nation and other nations of the free world, as McMaster hopes? Only history will judge if he is correct and if he is successful in inspiring a “vibrant, thoughtful, and respectful discussion of how [Americans] can best defend the free world and preserve a future of peace and opportunity for generations to come.”

Col. Cole Kingseed, U.S. Army retired, a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate in history from Ohio State University.

* * *

Books Tackle a Notable Army Attribute

The Character Edge: Leading and Winning with Integrity. Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Robert Caslen Jr. and Michael Matthews. St. Martin’s Press. 352 pages. $28.99

The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience, and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World. Shannon Huffman Polson. Harvard Business Review Press. 240 pages. $28

By Lt. Col. Joe Byerly

Throughout an Army career, soldiers hear leaders talk about the importance of character. Character is one of the Army’s leadership attributes. Character is mentioned over 50 times and gets its own chapter in Army Doctrine Reference Publication 6-22: Army Leadership. And when we read and talk about it, it’s usually accompanied by words such as “ethics” and “morals.” But what is it, really? What does character look like in practice? Is our character fixed or can we improve it? Can we lose it along the way?

Two recent books answer these questions and tackle character from different, but complementary, angles, and both are worthy reads on the subject. The first is The Character Edge: Leading and Winning with Integrity by retired Lt. Gen. Robert Caslen Jr. and Michael Matthews. The second is The Grit Factor: Courage, Resilience, and Leadership in the Most Male-Dominated Organization in the World by Shannon Huffman Polson.

In The Character Edge, Caslen and Matthews address character from two lenses. The first is from Caslen’s experiences in the military, specifically in combat and as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, from 2013 to 2018. The second lens is through Matthews’ academic background as a psychologist. The authors review the scientific research on character and provide readers with recommended tests as a tool for reflection as well as cite numerous studies on character and their findings.

Caslen and Matthews use the research of positive psychologists Martin Seligman and Christopher Peterson as the basis of the book. Seligman and Peterson classify 24 character strengths into six categories, which they call moral virtues. These categories are wisdom and knowledge; courage; justice; humanity; temperance; and transcendence. The Character Edge argues that in understanding which character traits we’re strongest in, and which ones we are weaker in, we can nurture and grow to be better leaders and better people. Throughout the book, Caslen and Matthews provide readers a mix of real-world examples and exercises they can do to improve their character.

The second book focuses on cultivating grit, which Caslen and Matthews also argue is an essential part of strong character. The Grit Factor is written by a former Apache helicopter pilot who left the Army after eight years and went into the private sector. For the book, Polson interviewed women who broke the “brass ceiling” in the military. They range from the first female pilot to fly with the Navy’s Blue Angels to the first women to graduate from U.S. Army Ranger School. Polson mixes their stories with her own and with academic research to produce a great book on what it takes to cultivate and strengthen grit.

An added benefit of reading The Grit Factor is that it helps men in the military better understand what women in uniform go through. Polson addresses many of the problems that women encounter when serving in organizations where they are the minority. For instance, she addresses women getting left out of camaraderie-building events because they aren’t “one of the guys.”

I recommend both books to leaders looking to focus on a practical approach to improving and strengthening character within themselves or their organizations. By taking the free character assessments and using the book as a road map, readers of The Character Edge will be able to take actionable steps to improve their own character and well-being. I also recommend The Grit Factor, as it will help inform leaders at any level who want to build strong inclusive cultures within their organizations.

Lt. Col. Joe Byerly is an armor officer and recently served as a special adviser with the U.S. Special Operations Command. He is a Non-Resident Fellow with the Modern War Institute at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and is the founder of the website From the Green Notebook.

* * *

WWII Cartoons Take on Serious Topics

Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin. Edited by Todd DePastino. Pritzker Military Museum & Library. 224 pages. $35

By Michael Robbins

The World War II cartoons of Bill Mauldin, featuring his weary, grimy U.S. Army infantrymen Willie and Joe, are among the most instantly identifiable American images of that conflict. They are right up there with the Marines raising the Stars and Stripes at Iwo Jima, Gen. Douglas MacArthur wading ashore in the Philippines, and soldiers advancing toward Omaha Beach in France on D-Day.

The 150 cartoons, selected from a trove of some 4,500 images in the Pritzker Military Museum and Library, are the main event in this handsome new book, Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin.

But the book and storied life of Mauldin, the soldier, artist, writer, war correspondent, movie actor and wicked-witted political commentator, are full of surprises. In his introduction, editor and historian Todd DePastino notes that Mauldin’s “wild fifty-year career” was the antithesis of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that “there are no second acts in American lives.”

Mauldin’s multiple “acts” are chronicled here in a series of essays by notable contributors including DePastino, who published a full biography, Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front, in 2009; actor Tom Hanks, who in his preface notes that “Mauldin reported the war as well as any correspondent,” and did so taking up only a few square inches regularly in Stars and Stripes; and retired Lt. Col. Jennifer Pritzker, founder and chair of her namesake museum and library, who credits Mauldin’s art with opening her eyes to “the reality of life in the military.”

Former NBC Nightly News anchor Tom Brokaw contributes a heartfelt “Thank you” to Mauldin for his 1945 book Up Front, which, upon its arrival at Brokaw’s boyhood home, quickly became an obsession that included memorizing the cartoon captions. It also became the “primary connection to the reality of war” for the eventual author of the best-selling book The Greatest Generation. In his essay, Brokaw traces Mauldin’s early life from a “hardscrabble childhood” in the rural Southwest through the drive and passion in acquiring and honing the artistic skills that brought Mauldin a Pulitzer Prize at the age of 23.

Other contributors fill in the successive “acts” in Mauldin’s dramatic career: his service in the 45th Infantry Division as a soldier, then as cartoonist for the division’s newspaper and eventually Stars and Stripes, which led to fame; Mauldin’s own rocky transition to civilian life in a transformed country and his visual reportage of America’s veterans’ homecoming in the 1947 best-selling book Back Home; Mauldin’s views on the commonalities of soldiering in the Korean War, the Vietnam War and even the American Revolution; and his pervasive influence on military cartooning.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the book, to those who know Mauldin only through Willie and Joe, is his postwar social consciousness and support of civil rights, reflecting his empathy for “common” soldiers and civilians alike. Mauldin’s passionate indignation at injustice and discrimination fairly leaps off the pages of his political cartoons, his reporting and his editorial commentaries in major newspapers and in his later books.

For much of his improbable career, Mauldin was a true champion of the downtrodden and the mistreated everywhere in American life.

Michael Robbins is a former editor of Military History magazine and MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.

* * *

Nurse Battles Red Tape for Recognition

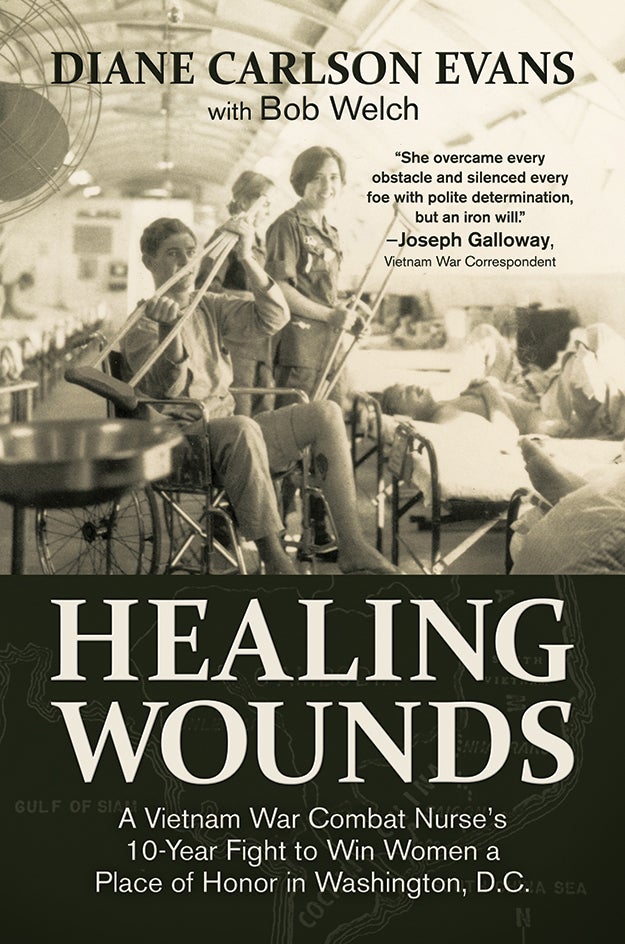

Healing Wounds: A Vietnam War Combat Nurse’s 10-Year Fight to Win Women a Place of Honor in Washington, D.C. Diane Carlson Evans with Bob Welch. Permuted Press. 288 pages. $27

By Kayla Williams

In Healing Wounds: A Vietnam War Combat Nurse’s 10-Year Fight to Win Women a Place of Honor in Washington, D.C., Vietnam veteran Diane Carlson Evans, with Bob Welch, offers a readable tale of her wartime service—and the lengthier battle to have the experiences of military women in the Vietnam era recognized at home.

Evans’ description of the brutality of war and how it steals idealism and forces soldiers to emotionally detach and compartmentalize in order to do their jobs resonates. Evans’ vivid descriptions of serving as an Army nurse in Pleiku capture how caring for the wounded—fellow soldiers as well as Vietnamese children—led to deep trauma. “For grunts, the sound [of a medevac helicopter] was a benevolent god with rotor blades; for nurses, an adrenaline-pumping bird that brought us merciless, soul-harrowing work,” she writes.

Evans also delves into the unique experiences of women, who had to fear not only enemy action but also sexual harassment and assault by men they served with, knowing the military would not protect them from retaliation if they reported. She recounts multiple incidents of inappropriate advances by officers who significantly outranked her.

Once back in the U.S., Evans struggles with the warring emotions of being proud of her service while also suffering from deep pain and numbness. Carlson writes poignantly about the difficulty of coming home, no longer feeling “necessary,” and being unable to relate to her generation, family or country. Her reaction to these complicated feelings was a not-uncommon unwillingness to talk about the war at all—until she attended the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—“the Wall”—in Washington, D.C.

Inspired and frustrated by the absence of women’s representation, in 1984, she and a small group of other Vietnam veterans, including another former Army nurse, launched the nonprofit Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project. After years of organizing, fundraising and jumping through bureaucratic hoops, she and a team of dedicated supporters—despite constant pushback from detractors—succeeded in getting a bronze statue of three women in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps caring for a wounded soldier placed near the Wall and the Three Servicemen statue.

Their organizing effort required obtaining approval from the newly formed Commemorative Works Act as well as the secretary of the Interior Department, the Commission on Fine Arts, the National Capital Memorial Advisory Commission and the National Capital Planning Commission; major fundraising; gaining political support; and navigating the politics of both the veterans movement and the federal bureaucracy.

She showed steely resolve in accomplishing her goal: “It had taken seven years of testimony before Veterans Service Organizations, three federal commissions, and two congressional bills for us to succeed.”

Evans held firm to her vision throughout the long struggle, yet her unwavering focus was not selfish. It was on securing a memorial that would recognize all women who served in the Vietnam era and provide them with healing and connection.

One of the speakers at the dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial called Evans “the most tenacious, determined, ferocious, single-minded woman I have ever known.” Inspired readers may find themselves inclined to agree with this assessment.

Kayla Williams is a senior fellow and director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security, Washington, D.C. She is the author of Love My Rifle More Than You: Young and Female in the U.S. Army.