January 2019 Book Reviews

January 2019 Book Reviews

Market Garden Was an Operation Too Far

The Battle of Arnhem: The Deadliest Airborne Operation of World War II.

Antony Beevor. Viking Press. 480 pages. $35

By Col. Cole C. Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Operation Market Garden, British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s ill-fated attempt to end the European war in the fall of 1944, was the largest Allied airborne operation of World War II. The audacious plan called for the capture of a series of bridges leading to the Lower Rhine. Cornelius Ryan’s A Bridge Too Far has long since been the standard examination of this campaign, but on the eve of Market Garden’s 75th anniversary, British author Antony Beevor brings his considerable literary talents to examine the battle for “a bridge too far.”

Beevor is the internationally acclaimed best-selling author of 10 books on World War II, including D-Day: The Battle for Normandy; Stalingrad: The Fateful Siege: 1942–1943; The Fall of Berlin 1945; and Ardennes 1944: The Battle of the Bulge. The recipient of the 2014 Pritzker Military Museum & Library Literature Award for Lifetime Achievement in Military Writing, Beevor was even knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. What separates Beevor’s account from Ryan’s is Beevor’s detailed description of the campaign’s aftermath and his willingness to affix accountability for the Allied failure.

Beevor’s narrative relies extensively on the international accounts of the campaign’s participants and Ryan’s private papers housed in the Alden Library at Ohio University. Beevor’s study spans the time Montgomery conceived the operation through the paratroop drop on Sept. 17, 1944, to the evacuation of the British 1st Airborne Division eight days later. In the process, Beevor avoids the pitfall of many military historians who view World War II through nationalistic eyes. Indeed, Beevor chastises virtually every senior commander in the Allied camp.

In hindsight, the fundamental concept of Operation Market Garden defied military logic, Beevor attests, because it made no allowance for anything to go wrong, nor the enemy’s likely reactions. Supreme Commander U.S. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was fond of saying that before the battle is joined, plans are everything, but once the battle is joined, plans go out the window. Nowhere was this adage more applicable than Market Garden, which ignored the maxim that no plan survives initial contact with the enemy.

To the Allied soldiers who fought the Wehrmacht during the airborne operation, Beevor affords high marks for their tenacity and bravery against overwhelming odds. British Lt. Col. John Frost’s 2nd Battalion, which had the mission to hold the Arnhem bridge, receives extraordinarily high accolades. So does U.S. Maj. Julian Cook’s 3rd Battalion of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment that paddled across the Waal to seize the northern end of the Nijmegen bridge on Sept. 20, 1944.

Lost in most histories of Operation Market Garden are the suffering and hardships endured by the Dutch civilians, and this is where Beevor makes his greatest contribution. He is superb at describing the “Hunger Winter” of 1944–45 that led to nearly 20,000 civilian deaths as a result of starvation and forced labor by the victorious Germans. The cities of The Hague, Amsterdam and Rotterdam were the most vulnerable to starvation because of the size of their populations. Between the termination of fighting around Arnhem until war’s end in May 1945, the daily ration of the Dutch citizenry was “reduced from 800 calories a day to 400, and then to 230.” The Netherlands’ official history records an estimated total of more than 3,600 civilian deaths in Operation Market Garden. According to Beevor, the reconstruction of Arnhem was finally completed in 1969.

Why did Operation Market Garden fail to meet its objectives? Beevor castigates the Allied high command, particularly Montgomery, for the operation’s failure. In spite of the catastrophic losses—Allied casualties in Market Garden totaled 17,000—“the self-congratulation and buck-passing among senior Allied commanders was bewildering.” Montgomery judged the operation a 90 percent success, but Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands was closer to the mark when he opined, “My country cannot afford another Montgomery victory.”

In the final analysis, Beevor adds to his laurels in his account of this controversial campaign. Even though Ryan’s masterpiece remains the standard against which every study of Market Garden is measured, The Battle of Arnhem is a worthy supplement and marks Beevor as one of the premier military historians of the European Theater.

Col. Cole C. Kingseed, USA Ret., a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate from Ohio State University.

* * *

Navigating Like Foxes and Hedgehogs

On Grand Strategy. John Lewis Gaddis. Penguin Press. 384 pages. $26

By Maj. Joe Byerly

There’s a scene from the 2012 film Lincoln in which racial-equality advocate Thaddeus Stevens asks President Abraham Lincoln how he could have a noble cause in wanting to emancipate the slaves, yet resort to deals, bribes and lies to get members of the House of Representatives to pass the 13th Amendment. The president responds with a lesson he learned as a child: “[A] compass [will] point you true north from where you’re standing, but it’s got no advice about the swamps and deserts and chasms that you’ll encounter along the way.”

In this apocryphal scene, Lincoln shows Stevens that he possesses a vision but understands the environment in which he must operate to see it succeed.

This is one of the many passages throughout John Lewis Gaddis’ On Grand Strategy that he uses to make the case for what is required to be successful at grand strategy. He walks readers through 10 historic case studies, beginning with Persian King Xerxes and ending with the Cold War to illustrate contradictions leaders and strategists face. For instance, he shows how President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized the threats in Europe and Japan in the late 1930s and knew the U.S. needed to be prepared militarily, but also understood Americans’ desire to remain neutral and avoid war. So he built preparedness under the auspices of his New Deal. Roosevelt, like all those profiled by Gaddis, successfully navigated the contradictions because they were the foxes and the hedgehogs.

This animal reference dates to Greek poet Archilochus (680-643 B.C.) who wrote, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” It is part of a fragment of a passage that survived, although the context did not. Sir Isaiah Berlin revived it in a 1953 essay on Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, and the expression outgrew the essay itself. Throughout On Grand Strategy, Gaddis shows that a good strategist must be able to adapt as the situation changes (fox), but also possess the patience to see their idea through to the end (hedgehog).

Each essay in the book features leaders he believes possessed both traits, and knew when to be one or the other. The only exception is the case study he opens the book with featuring Xerxes and his uncle Artabanus. Here he shows the polarity between the two schools of thought. Gaddis’ profiles include the Emperor Augustus, Queen Elizabeth I, the Founding Fathers, Lincoln, Roosevelt and others. All these leaders had long-term visions and skillfully navigated the circumstances that stood in the way of them achieving their vision.

If readers have a weak foundation in the time periods discussed in the book, they might struggle to understand some of the context in which the profiled individuals made decisions. Nevertheless, Gaddis provides enough evidence to support his thesis that those he covers are both hedgehogs and foxes.

Overall, this book would appeal to two audiences. First to those who may find themselves in the role of strategist or leading at a strategic level, On Grand Strategy should be recommended reading. The second audience is those who create long-term personal or professional goals for themselves.

Outside this book’s relevance in the national security realm, Gaddis has also produced a strong philosophy for life: While your goals might be infinite, there are realities you must navigate to achieve them. To be successful you need to connect the two.

Maj. Joe Byerly is a planner with the U.S. Special Operations Command and a non-resident fellow with West Point’s Modern War Institute. Previously, he was brigade executive officer for the 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, Colo. He runs a website called From the Green Notebook.

* * *

Mending Racial Divide With Blood and Bullets

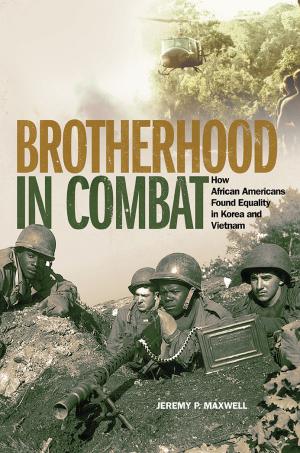

Brotherhood in Combat: How African Americans Found Equality in Korea and Vietnam. Jeremy P. Maxwell. University of Oklahoma Press. 224 pages. $29.95

By Gina M. DiNicolo

In his intriguing social and military/political history of racial integration in the Army and Marine Corps during the mid-20th century, Jeremy P. Maxwell deftly recounts this complex topic with a well-organized narrative, references from historical luminaries and accounts from the men who fought in the killing fields.

In Brotherhood in Combat, Maxwell begins with an introduction that leaves the reader wanting more information—and he delivers in subsequent chapters.

Maxwell links the military’s integration of black Americans to the writings of military theorist Carl von Clausewitz and sets the book’s pace and tone from the outset. He builds his history starting with the broader backstory of his topic and moves with ease to military racial integration. He identifies and explains his references, making his work enjoyable and approachable on many levels. As he notes, the military went from meaningless integration on paper to near-raceless units under fire. He enthralls with the forward momentum of his clean narrative and seamless mix of political and military accounts.

It was President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981 that mandated equality of military males regardless of race. But the realities of a gutted post-World War II force delayed much adherence to Truman’s order. Maxwell refers to a period of racial upheaval. He shows the tensions between black and white leaders and the cruel discrimination faced by the average black male. Race plays against the backdrop of politics. To Maxwell’s credit he never overstates.

Maxwell describes the difficult road all traveled to achieve racial progress during Korea’s early days and the follow-on success brought by combat. He jumps to Vietnam with a hefty political discussion but no mention of the military services and integration between the two wars. He hits upon the socio-economic disparities brought on by the Vietnam-era draft and its effect on poor black males, impacting their choice of MOS and chance for promotion. In Vietnam, again, the rigors of combat and shared experience under fire broke down racial barriers. In contrast, soldiers in noncombat specialties, those in the rear, suffered racial acrimony. Maxwell employs oral histories to illustrate his points.

The reader can see that the armies of Korea and Vietnam differed as did American society of the two periods. The civil rights movement in the U.S. burned, as did the controversial military operations in Southeast Asia. The draft and the prevalence of drugs, as the author mentions, impacted Army race relations during Vietnam. While one would not want to address race in a vacuum, the history of military racial integration during the mid-20th century could benefit being told in two volumes. Additional primary source citations would strengthen an already credible work.

Similarly, Maxwell’s account of the Army and integration overshadows the one presented for the Marine Corps. Though both services experienced ground combat as well as the draft, their similarities do not go much further. The Marine Corps’ struggles with equality could occupy their own book. But authors make choices, and Maxwell’s decision to handle the two services and two wars in one work does not degrade his account.

Brotherhood in Combat tackles the timeless topic of change. One can see a similar, challenging path for the U.S. Army with post-1970s gender integration as well as other recent social issues. One can also look at the changes in the Army as a fighting force with its move to a modular configuration early in the century, as well as soldiers’ and Marines’ modified fighting tactics in Iraq and Afghanistan brought on by necessity.

Readers, regardless of background, will find exacting historical research and a thought-provoking story in Brotherhood in Combat.

Gina M. DiNicolo is a military historian, author and journalist. Her works include The Black Panthers: A Story of Race, War, and Courage: The 761st Tank Battalion in World War II. She is a retired Marine Corps officer and a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md.

* * *

Image Collection Takes Fresh Look at WWI

Lest We Forget: The Great War: World War I Prints from the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. History by Michael W. Robbins. Pritzker Military Museum & Library. 400 pages. $60

By Edward G. Lengel

World War I produced a striking array of visual artifacts, ranging from art and propaganda to photographs and film, in full color and black and white. History enthusiasts of a certain age will remember plowing through school libraries in search of illustrated histories by American Heritage and others, marveling at images of police apprehending Gavrilo Princip after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand; German troops wearing spiked helmets marching through French cornfields; artillery opening fire on the Somme; biplane fighters preparing for takeoff; and half-decayed corpses in muddy trenches. The generally poor quality of those photographic reproductions reinforced the sense that World War I was a far-off, mysterious, unfathomable conflict.

Several coffee table-sized illustrated histories of the war have been published since those early publications, many of them over the past decade. Even more visual material has been made available on the internet. Institutions such as the Library of Congress and the National Archives have digitized portions of their collections and made them available to the public. Museums, libraries and individual collectors in Canada, Australia, Great Britain, France and Germany have likewise produced a dizzying array of visual content, much of it never seen before. Where the Great War once seemed strange and mysterious, it now appears almost overwhelming. Where should readers—hopefully including curious students—begin?

Lest We Forget: The Great War recaptures some of that sense of historical awe and intrigue, rescuing it from the information age’s sweeping flood of data. Arranged in 20 short but beautifully illustrated chapters, with text by Michael W. Robbins and an introduction by Sir Hew Strachan, this book includes full-page color reproductions of dozens of contemporary posters and illustrations from the Pritzker Military Museum & Library collection, complemented by black-and-white photographs. Detailed color maps head each chapter. Content is arranged to provide a summary view of the war’s course from 1914 to 1918, almost entirely in Europe, although passing reference is made to the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the war at sea.

Most of the color illustrations are posters, some of which have been widely reproduced and will be familiar to readers. A good number, however, are taken from illustrated magazines and other contemporary publications that have rarely appeared in public before and will hold particular interest for scholars and aficionados of early 20th-century popular art. Especially compelling are the rare and visually striking Russian and Eastern European posters and prints that provide new insight into the war on the Eastern Front.

A disproportionate number of the color illustrations are American, reflecting the collection from which they originate. But what a rich collection. Here again, although deservedly popular Marine and Navy recruiting posters, as well as Red Cross and War Bond art, will be familiar to most readers, a good number of these have rarely if ever appeared in print.

The collection is not of course representative of the multidimensional global conflict known as World War I. There’s little here on the war outside Europe, or the participation of non-Europeans such as Australians, Senegalese, Moroccans or Indians in the fighting on the Western Front or in the Middle East. The war in the air receives scant attention. But these are quibbles. Lest We Forget is a visual feast likely to interest art historians and the general public, and to surprise and intrigue even the most jaded students of World War I.

Edward G. Lengel is an independent military historian. He serves as an adviser to the World War I Centennial Commission and is the author of Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War’s Lost Battalion.

* * *

Using Special Forces Culture to Create Success

Conquer Anything: A Green Beret’s Guide to Building Your A-Team. Greg Stube With Frank Miniter. Post Hill Press. 208 pages. $26

By Mike Guardia

Conquer Anything is a leadership book like no other. The author, Greg Stube, is an Army veteran of 23 years, 19 of which he spent in Special Forces. During his last combat tour in Afghanistan, Stube was critically wounded during the Battle of Sperwan Ghar and his wounds effectively ended his military career. But what he lost on the battlefields of Afghanistan, he gains tenfold within the pages of Conquer Anything.

Stube frames his leadership philosophies against the backdrop of special operations culture. He points out that successful leaders are those who develop and maintain the best teams. Success in any organization, business or military, begins and ends with team synergy. For if the team members know their mission, their respective jobs and have abiding trust in one another, that team can effectively conquer anything.

In this regard, Stube makes a clarion call to business leaders by telling them to empower their teams with a degree of autonomy. It’s a strong case for the decentralization of power in an organization. Stube writes: “In the Green Berets, you are not handed a mission plan and simply told to follow its steps. [An] A-Team has been trained physically and mentally to write and execute missions. What we are given are constraints, restraints, and available military intelligence to develop the mission according to our strengths and weaknesses. Empowering a team this way leads to unexpected solutions and tends to bring the best out in people. They become a part of the mission, not just a pawn.” Effectively, giving team members an active role in the planning process inspires their creativity and motivates them to perform better.

Still, Stube is careful to point out that having an energized team begins with having a level-headed leader. Leaders must know what their goals are, what their vision is, what their values are and whether the endeavor is right for them. Although a team can achieve greatness with the right leadership, Stube warns that the team must not alienate its support system. This is a strong parallel to military culture—front line fighters are glorified, and rightfully so, but that often comes at the expense of overlooking support personnel (administrative, supply and human resource managers) who work behind the scenes to keep the organization running.

This book is laced with powerful anecdotes to remind the reader that success lies in using common sense and remembering the basics. Too often, leaders—and aspiring leaders—get caught up in theoretical notions of leadership and abstract concepts of teamwork. These lofty ideas promise success but often backfire due to poor execution. Stube reminds the reader: “Thinking outside the box seems to be a popular concept right now. … The experts are everywhere. But I say that we are better as individuals and as teammates if we focus less on getting outside the box, and get back into rehearsing fundamentals in any discipline. … We are more prone to making big errors while trying to be too advanced in what we do.”

The corollary to this concept is that quality rehearsals (or lack thereof) can make or break a team when it’s time for execution. As the old saying goes, “The more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war.”

Conquer Anything is a superb leadership book. Stube offers resoundingly practical advice for any leader who wishes to inspire their team. Without being theoretical or pedantic, Stube has applied Special Forces culture to create a blueprint for success in any organization. This book is highly recommended.

Mike Guardia served six years in the Army as an armor officer. He is a military historian and the author of Hal Moore: A Soldier Once … and Always and co-author of Hal Moore on Leadership: Winning When Outgunned and Outmanned.