December 2018 Book Reviews

December 2018 Book Reviews

Enthralling Boots-on-the-Ground View of War

The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. C.J. Chivers. Simon & Schuster. 400 pages. $28

By Capt. Garrison Haning

So much attention is paid to the large troop movements of war. History dwells on the events that set the military-industrial complex to work, churning out combat power. But the true price of battle is not paid by institutions, squadrons or brigades. It is paid by the people in those formations. The Fighters is written for the reader who wants to stand in the formation.

The quotes author C.J. Chivers opens the book with illustrate this well. From Homer’s The Iliad:

Why,

it seems like only yesterday, or the day before,

when our vast armada gathered …

And: “America is not at war. / The Marine Corps is at war; / America is at the mall,” handwritten on the wall of the government center in Ramadi, Iraq, in January 2007.

This book is not an armada view of war. Chivers, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The New York Times, bypasses the heady Pentagon meetings and massive troop movements, opting to view the war through a different lens: the iris of a fighter. He places the reader in a C-130 loaded with Humvees, amid ammunition, jerricans of diesel and water, and pouches of chewing tobacco, with a special operations team en route to an abandoned airfield in southern Iraq. He walks the reader, step by step, through how those Humvees wound up in the back of the C-130. Then he places the reader into those Humvees, intimately introduces the men who will drive them into battle, and tells the story of the first time they get shot at.

If you’ve ever wondered what infantrymen do immediately after they get hit by an IED and survive, you’ll find out in this book. (For the inquisitive reader, a spoiler: The pattern is to check that you’re alive, find your gun, then check your genitals, and it makes sense; no matter which one you’ve lost, you’re a dead man.)

So too, Chivers walks the reader through a decision faced by any combatant fighting in an area prone to indirect fire attacks: to sleep or not to sleep through nighttime mortar and rocket fire. On the one hand, with rockets incoming, a bunker can be a comforting place to dive into. On the other hand, when the bunker isn’t strong enough to withstand a direct hit, it is important to consider the cost-benefit between jumping out of bed and taking cover versus sleeping through the attack and waking up well rested and alert for the next morning’s patrols … assuming morning comes.

At its heart, The Fighters is a collection of deployment stories from six members of the military spanning the gamut from aviators to corpsmen to Special Forces operators to infantrymen. And the details are what make the book enthralling and substantial, but they are also what make it sickening and heartbreaking.

Take, for example, the story of hospital corpsman Dustin Kirby. As a young man whose family hoped he’d be safe when he enlisted in the Navy, his time in Iraq starts relatively slow. Mired in a “lethal puzzle with a feel-good [counterinsurgency] doctrine and a small crew,” as wars so often are, engagements with the locals quickly gravitate toward the kinetic.

Walk with Kirby as again and again he tries to save his wounded comrades from brain-damaging sniper rounds and face-destroying shrapnel. Follow Kirby through his cycle of boredom, adrenaline and crippling survivor guilt until the cycle is finally broken when Kirby receives his own wounds, taking a sniper round to his face. Then watch as Kirby scrambles around the rooftop he is shot upon and tries to collect pieces of his teeth and jaw from the dust, in hopes he’ll be able to have his mouth put back together by a surgeon, assuming he doesn’t bleed out.

But Chivers goes well beyond where other writers would stop. A theater view of war doesn’t do the individual fighter justice. Instead, the book affords a view of Kirby’s medicine cabinet as he tries to wean himself off painkillers and antidepressants while he works through his injuries stateside. And the reader stands with Kirby’s family and friends as they begin losing him to post-traumatic stress disorder, after nearly losing him in combat.

Immersive, frustrating, captivating, at times funny, and heartbreaking, make no mistake: This is not an uplifting read. It is painful and tragic, like the lives of many fighters.

The view from the theater level of war has its place in American history. The tinsel and glare of formations of soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen marching off to battle is a sight to behold; as such, anyone can write about that.

With this book, Chivers makes sure not to lose the fighter for the formation. In his writing, the toll of war, paid by the individual, is preserved. He dwells on things not evident from the bleachers of a drill field or the cordoned-off streets of a parade route. He revels in privileged information, normally reserved for the few who wear a uniform and are fortunate enough to learn its nuances. The Fighters is a book for the reader who wants to stand in the formation.

Capt. Garrison Haning, USAR, deployed to Iraq in 2011 as a platoon leader with the 1st Cavalry Division and served as a battery commander at Fort Sill, Okla. He is a 2009 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy.

* * *

Cartoons Energize Ancient Text

The Art of War. Sunzi. Adapted and illustrated by C.C. Tsai. English translation and introduction by Brian Bruya. Princeton University Press. 144 pages. $22.95

By Randy Brown

Any military leader who has black-marker-briefed a battle on butcher block paper, or fought back the fog of war with a chalkboard eraser, or even drawn in the dirt with a pointed stick, knows the primal decision-assisting and communications power of making cartoons. A decent sketch, after all, can instantly simplify and shape the presentation of complex information, even when the best that one can render is rally points and arrows.

Imagine, then, how effective an experienced cartoonist might be at the same task.

Armed with The Art of War, the familiar military strategy primer written by 5th century B.C. warrior-philosopher Sunzi, more well known as Sun Tzu, Taiwan-born cartoonist C.C. Tsai elevates the well-traveled text and makes it more accessible. Whether old soldiers or future recruits, readers will be sure to enjoy how the artist injects the ancient words with a creative energy worthy of Bugs Bunny.

Tsai was born in Taiwan in 1948 but now resides in Hangzhou, China. His cartoons, which often illuminate works of Asian literature and philosophy, have been published widely in other books and outlets worldwide.

A recent Princeton University Press edition presents The Art of War as a nearly 9-inch-square, 144-page black-and-white paperback. A simple matte white cover features the duotone image of a Chinese general—perhaps Sunzi himself—rendered in Tsai’s signature style.

Tsai gets a lot of life out of a line of black ink. The artist’s images are constructed of elegant loops and curves, which he deploys with sage economy of force upon the terrain of the page. His style evokes Al Hirschfeld’s caricatures of 20th-century Hollywood and Broadway personalities, combined with the punchy, goofy storytelling of Sergio Aragonés (creator of MAD magazine’s long-running “Marginal Thinking” feature, as well as Groo the Wanderer).

The book’s interior presents Tsai’s cartoons in four- to six-panel salvos. Often, a single page or spread serves to communicate a whole subchapter. “Control Others Instead of Being Controlled” is one such example, as is “Move Only when It Benefits You.” The easy-to-locate section titles serve as waypoints, offering browsers opportunities to jump in and out of the text. This is a book that welcomes casual, random and repeated visits.

Do not mistake a capacity for whimsy for a lack of intellectual heft, however. The translations of Sunzi’s original text are presented in vertical strips on each page, mimicking the bamboo tablets upon which some of the writings were discovered in modern times. In his introduction to the book, translator and professor of philosophy Brian Bruya—his are the English-language words that fill the dialogue balloons of Tsai’s cartoons—notes: “In working with the classics, C.C. stays close to tradition, and in his illustrations he more or less follows the prominent commentaries.”

Depending on the translation or edition, The Art of War presents itself to modern eyes and ears variously as poetry, military philosophy or business management how-to. There are fancy coffee table and gift-presentation editions, and there are low-budget field-expedient reprints one can stuff into a cargo pocket.

The Princeton University Press collection of Tsai’s Art of War cartoons and translations, however, is something unique: a fresh and approachable way through which to engage the work and to share it with others. An Art of War, if you will, that’s fun for the whole family.

Randy Brown embedded with his former Iowa Army National Guard unit as a civilian journalist in Afghanistan in 2011. A 20-year veteran with an overseas deployment, he subsequently authored the poetry collection Welcome to FOB Haiku: War Poems from Inside the Wire. He blogs about citizen-soldier culture at www.redbullrising.com and about military-themed writing at www.aimingcircle.com.

* * *

Military Women Progress; Afghan War Doesn’t

Beyond the Call: Three Women on the Front Lines in Afghanistan. Eileen Rivers. Da Capo Press. 288 pages. $27

By Kayla M. Williams

Women’s representation in the armed forces has never equaled their proportion of the general population, and the number of volumes about their military participation has traditionally been even more limited. In recent years, as the public has gradually taken notice of the rapid expansion of women’s roles in the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, that has begun to change: There has been significant growth in the number of books by and about military women.

Beyond the Call: Three Women on the Front Lines in Afghanistan by Eileen Rivers fits both categories. She is an Army veteran who served in Kuwait during the aftermath of the First Gulf War who has since spent over 15 years in journalism, reporting on veterans’ issues at The Washington Post and then becoming an editor and editorial board member at USA Today. In this volume, Rivers combines in-depth personal accounts of the experiences of three women involved in the Female Engagement Team (FET) initiative in Afghanistan with brief overviews of the history of women in the military and a deep dive into the personal history of an Afghan woman.

Stories of how women on FETs contributed to military missions in Afghanistan are compelling and rich in detail, providing useful color to those interested in U.S. involvement there. However, it is difficult to square assertions that their presence was instrumental in strategic success or vital to turning the tide of the war considering widespread reporting (occasionally acknowledged in Beyond the Call) that there has been little to no genuine progress in Afghanistan. Tales recounting the need for multiple iterations of deployed personnel to repeat the same missions building relationships with local villages, training Afghan forces and building local infrastructure build toward an exhausting sense of futility that stands in stark contrast to the incontrovertible progress of women within the U.S. military.

That progress is somewhat downplayed in this volume. When recounting policy changes, Rivers focuses on a relatively minor 2012 revision to, rather than the much more significant 2013 elimination of, the 1994 Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule. She implies on multiple occasions that limitations on FET activities, such as driving or walking off forward operating bases, were because they were women, rather than part of theaterwide regulations on the number of vehicles and/or personnel required for a mission. Rivers’ phrasing also gives the impression that FET activities should have stood alone, rather than supporting commander’s intent and nesting within the overall mission.

The narrative timeline can be difficult to follow, as the stories jump between characters, locations and years; the historical grounding also hops disjointedly between branches of service, years and countries. The timing of Beyond the Call’s publication seems odd, since many of the stories take place before 2014 (with the awkward addition of an excursion into recounting the first women graduating from Ranger School)—yet it makes no mention of the all-female Cultural Support Teams that deployed with special operations forces, as detailed in Gayle Lemmon’s Ashley’s War.

Overall, the anecdotes presented in Beyond the Call will provide interesting color and compelling examples to those interested in the way policies are developed, how innovative military programs are implemented, the Afghanistan War, FETS specifically, and women in combat more broadly.

Kayla M. Williams is a senior fellow and director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security. She is the author of Love My Rifle More Than You: Young and Female in the U.S. Army.

* * *

POW Shares Nightmare of Swiss Captivity

Prisoner of the Swiss: A World War II Airman’s Story. Daniel Culler and Rob Morris. Casemate. 144 pages. $27.95

By Capt. Devon Collins

In 1995, Daniel Culler self-published Black Hole of Wauwilermoos to overcome the haunting nightmares of his captivity during World War II. In Prisoner of the Swiss, Rob Morris sets Culler’s story within the larger POW historiography and, specifically, neutral Switzerland’s treatment of those prisoners.

A forward by Dwight Mears, a former soldier himself and grandson of a POW, details the historical and legal origins of Switzerland’s neutrality during the war. Morris and Mears not only heighten our perception of an understudied realm of World War II captivity, but give a U.S. airman, betrayed by the very country he swore to defend, a means to heal.

Culler begins his story as a volunteer for the U.S. Army Air Corps in January 1942 following the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was finally admitted to serve as a flight engineer for a B-24 bomber crew at 18 years old. Following nearly two years of training, Culler ran 25 missions in just under four months over northwestern Europe in the 44th Bomb Group. While flying their 25th and thus last mission as a bomber crew, and just shy of his 20th birthday, Culler’s plane was hit by flak over Germany and the pilot was forced to land in Switzerland.

From the moment Culler and his crew stepped foot on Swiss soil they were treated as criminals, internees rather than prisoners of war. The distinction had significant and far-reaching implications for Culler. Switzerland took its neutrality to an extreme, so when Culler attempted to escape, he was sent to a federal prison. His crime was traveling in Switzerland without permission.

Deprived of due process or even the option of speaking with an American diplomat, both rights for any POW under the Hague and Geneva conventions, Culler was sent to the “gates of hell.” Once at Wauwilermoos, a prison camp for violent felons, Culler was subjected to the most brutal treatment. Stripped of his legal status as a POW, he was systematically stripped of his humanity through repeated torture and gang rape with the acquiescence, if not the blessing, of the sadistic camp commandant.

Unfortunately, Culler’s horrific experience did not end with his eventual daring escape from Switzerland. While debriefing the Office of Strategic Services about his internment, Culler was called a liar and told never to speak of his time in Switzerland with the express threat that his mental status, and even veteran benefits, would be called into question.

There is a stigma, whether justified or not, associated with prisoners of war. The societal shame of capture and internment forces many POWs to remain silent about the hardships they endured. Instead, some POWs hide that part of their service from even the most trusted confidants, including other soldiers.

Those who do put pen to paper about their experiences often stow those letters, diaries or memoirs away; forgotten until the passing of the soldier or a curious family member happens to stumble upon them. For Staff Sgt. Culler, his silence about internment went beyond fear of societal stigma. Besides being harangued and threatened by the U.S. Army, his service record never indicated he was a prisoner, thereby jeopardizing not only his physical but also his mental health.

Morris and Mears offer a semblance of justice to Culler where others failed. Where Morris gives life to Culler’s voice, Mears gave him public acknowledgement as he diligently pursued the awarding in April 2014 of the U.S. Prisoner of War Medal to 143 airmen interned during World War II in Wauwilermoos.

Capt. Devon Collins is an instructor in the Department of History at West Point, from which she graduated in 2008. She previously served in multiple logistics positions in the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team and the 82nd Airborne Division. She expects to complete her doctorate in military history from Ohio State University in 2020.

* * *

Petersburg, From the James to the Crater

A Campaign of Giants: The Battle for Petersburg. A. Wilson Greene. University of North Carolina Press. 728 pages. $45

By Col. Cole C. Kingseed, U.S. Army retired

Among the major campaigns of the American Civil War, only Petersburg, Va., lacks an operational history of the events between June 1864 and April 1865. A. Wilson Greene strives to correct this imbalance in the first volume of a projected trilogy of the war’s concluding campaign in the Eastern Theater. Greene succeeds admirably with A Campaign of Giants, a comprehensive, scholarly study from the crossing of the James River on June 15, 1864, to the Battle of the Crater that July 30.

Greene has spent 25 years working and living on the Petersburg battlefields, first with the National Park Service and then as executive director of Pamplin Historical Park and its National Museum of the Civil War Soldier. Greene also authored The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion. His exhaustive research in A Campaign of Giants includes over 100 pages of notes, a comprehensive bibliography and highly readable maps that enhance the reader’s understanding of the Petersburg campaign. The lack of photos, however, is disappointing.

In compiling this narrative, Greene divides his study of the Battle for Petersburg into three phases. The first highlights the Union attack at Petersburg from June 15–18 that resulted in the capture of a large portion of Confederate defensive works but failed to capture the city. The second offensive, June 22–24, witnessed repeated Union defeats. The third offensive of July 26–30 featured the campaign’s most spectacular combat, the Battle of the Crater.

What makes A Campaign of Giants so riveting is Greene’s willingness to challenge historical conventions and address controversies that have intrigued scholars and readers for generations. Two aspects of this volume stand out: the significant role of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in combat and Greene’s assessment of the Union Army’s high command.

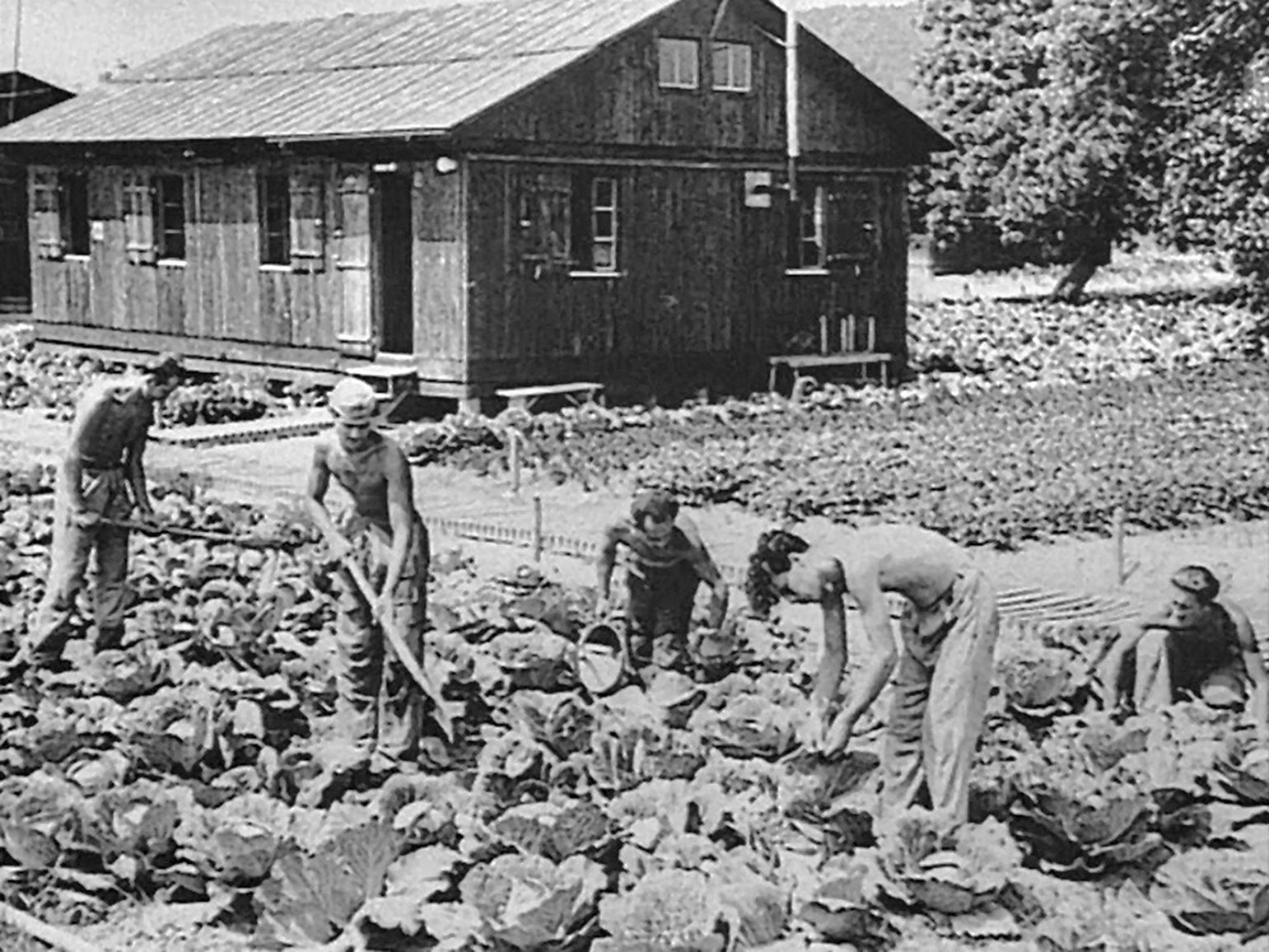

Black troops engaged in significant combat for the first time in the Eastern Theater during the Petersburg campaign. The USCT suffered a disproportionate number of casualties in the Battle of the Crater and endured unspeakable hardships once they surrendered. Greene posits that there were no repercussions from the Confederate authorities, military or civilian, for the wholesale violation of the accepted rules of war for treating the USCT so inhumanly.

With respect to the Union Army’s leadership, Greene finds Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s performance “disappointing” once the Army of the Potomac crossed the James. In similar fashion, the War Department’s resident informant, Charles Dana, repeatedly reported to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on July 7 that Army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade had created such a toxic command climate that he had lost the confidence of every one of his generals. Reported Dana, “I have long known Meade to be a man of the worst possible temper. I do not think he has a friend in the whole army.”

Few high-ranking Union officers at Petersburg emerged from the campaign more controversial than Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren, commanding general of the Army of the Potomac’s reorganized Fifth Corps, and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, commanding the independent Ninth Corps. According to one of the Army’s senior commanders, Meade “finds fault with Warren’s contradictory spirit which loves to do a thing by a different way from the one ordered.” As for Burnside, the Ninth Corps commander’s blundered attack at the Crater resulted in “the saddest affair” that Grant had witnessed during the war.

Greene concludes his narrative from the Union perspective by quoting from Meade’s July 31 letter to his wife, stating Grant had gone to see President Abraham Lincoln. “What the result will be I cannot tell, but matters here [in Petersburg] are becoming complicated.”

To understand Grant’s next step, readers will eagerly await Greene’s second volume of the war’s decisive campaign.

Col. Cole C. Kingseed, USA Ret., a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. He has a doctorate from Ohio State University.