April 2019 Book Reviews

April 2019 Book Reviews

Plotting a Course Through a Global Fight

Atlas of World War II: History’s Greatest Conflict Revealed Through Rare Wartime Maps and New Cartography. Neil Kagan and Stephen G. Hyslop. National Geographic. 256 pages. $45

By Capt. Jonathan D. Bratten

In time for the 75th anniversary of D-Day, National Geographic has released the Atlas of World War II. Now, one might think there are already plenty of resources such as this in the world of books. And further, that maybe the digital age has rendered things like atlases obsolete. But the Atlas of World War II manages to be relevant by relying on stunning primary sources.

It is one thing to say the Germans had a prodigious U-boat fleet, for example; but to demonstrate the potential impact of that fleet, National Geographic includes a German chart of northern New England’s coastline, with an inset for Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Maine. The war is suddenly made more imminent and personal for those living in the Northeast who might read this book.

This is the way the Atlas of World War II strikes at the reader and takes hold so you are unable to stop reading and studying. From the first pages, the reader is pulled in by the dynamic high-resolution photos and exquisite maps, charts and sketches. These are used in conjunction with well-written text. Editor Neil Kagan blends the writing of Stephen G. Hyslop with images and maps from Harris Andrews, Kenneth Rendell and Gregory Ugiansky to present a comprehensive, multisensory experience of the war.

Divided into five chapters, the Atlas of World War II begins with an overview of its core component: military maps. The work contains dozens of rare and never-before-published maps and charts. Many of them carry the handwritten notes of their bearers, providing a remarkable window in time through which to view the protagonists of the war. Allied and Axis maps are provided in vivid color. Aerial maps, invasion maps and escape maps, as well as sea charts, help the reader literally navigate through their understanding of World War II.

Subsequent chapters break down the runup to the war, the initial European and Asian conflicts, and then the scope of the conflict as more and more nations became involved. Going beyond the battlefield, the atlas covers other aspects of the conflict: guerrilla warfare, propaganda and the homefronts. And it does not shy away from showing—in gut-wrenching photos—the horrors of the Holocaust. Nor does the atlas avoid the story of Japanese-Americans who were interned during the war, even as many of them donned the uniform of the U.S. military.

In addition to the maps and action photos, carefully curated shots of artifacts dot the pages of this atlas, bringing yet another layer of historical interpretation to an already rich resource. The book spotlights artifacts such as the journal of Capt. Thomas Lanphier Jr., who sketched out the route he and 1st Lt. Rex Barber used to down the Japanese plane carrying Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto. And small compasses that could be concealed in buttons or pipes for Allied aviators in case they were shot down, to be placed on top of an evasion map.

During the war, National Geographic was deeply involved in the mission to provide readable maps to the American populace to help people see the impacts of the war and where their troops were fighting. In fact, it did more than just help educate, as illustrated in a vignette provided in the book that describes how a plane carrying Adm. Chester Nimitz went off course over the Solomon Islands and was righted only because one of the Marine officers happened to be carrying a National Geographic map of the region.

As a whole, the Atlas of World War II comes in at 256 pages of intricately worked primary sources that leave the reader stunned at the scope of the war. Some might complain that the book does not focus on one area more than others, but it offers good coverage of the war as a whole—although it does skew more to the U.S. and Great Britain than to the Soviet Union. (That said, it does cover the Eastern Front in detail as well.) Novices and experienced readers will find much to enjoy in this work, and again be astounded that the world could enter into such chaos and arrive out of it again.

Capt. Jonathan D. Bratten, ARNG, is an engineer officer in the Maine Army National Guard, in which he serves as command historian. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history.

* * *

Medic Serves, Sacrifices in the Jungle

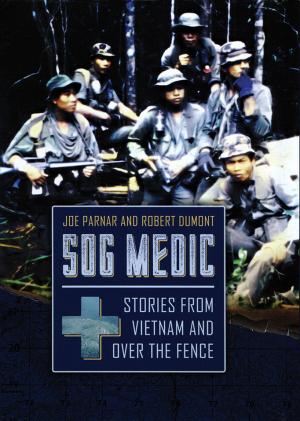

SOG Medic: Stories from Vietnam and Over the Fence. Joe Parnar and Robert Dumont. Casemate. 288 pages. $32.95

By Col. Leif G. Johnson, U.S. Army retired

This may not be the first book to draw your attention on the military history shelf at the local bookstore, but it is worth a second look. Joe Parnar and Robert Dumont have crafted a well-written, interesting account of Parnar’s three-year term of enlistment in the U.S. Army, culminating as a Special Forces medic in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969.

As the Vietnam War fades from America’s collective memory, SOG Medic triumphs as an important reminder of the duty and sacrifice of soldiers serving in the jungles of Vietnam. Chronological in format, introspective in content, this book provides an insightful, detailed narrative of Parnar’s experiences and those of his fellow soldiers.

A baby boomer whose uncle fought in the Battle of the Bulge, Parnar was motivated by his respect for “the greatest generation” to enlist in the Army. In 1966, U.S. involvement in Vietnam was ramping up and anti-war sentiment was gaining traction on campuses and across the nation. In counterpoint, the song the Ballad of the Green Berets by Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler was released early that year. Influenced by these factors and by the late President John F. Kennedy, Parnar decided to not just talk the talk, but walk the walk. Enlisting in the airborne infantry, Parnar traded his senior year at the University of Massachusetts for three years of wearing olive-drab green, fully expecting he would serve in Vietnam and do his part.

By the end of January 1967, Parnar had completed basic infantry training and Advanced Individual Training and earned his jump wings at Fort Benning, Ga. During AIT, Parnar had qualified and passed entry tests for Special Forces, a branch of service that had enjoyed the attention and admiration of JFK. As with many things in the Army, happenstance often trumps desire. In his case, Parnar’s inclination to train as a Special Forces engineer to blow up stuff was overcome by his academic credentials as a physical education major—and medic training at San Antonio started eight weeks sooner than engineer training. So, Spc. Parnar was trained as a Special Forces medic, shipped to Vietnam in April 1968 and found himself assigned to Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Studies and Observations Group (SOG).

Day by day, week by week, mission by mission, SOG Medic vividly depicts jungle combat with its hardships, challenges and mortality. It provides the reader with a good overview of the tactics, techniques and practices of small-unit operations—ground and air. It also provides an assessment of the more routine “garrison” times, depicting life at Forward Operating Base 2, located south of Kon Tum on the road to Pleiku in the tri-border region of Vietnam.

Through it all, Parnar introduces us to his fellow soldiers. This, for me, was the best part of the book. Parnar’s personal vignettes and anecdotes are proof of the professionalism, dedication and sacrifice of the soldiers who served with him.

Parnar takes the time to provide context, circumstance and motivation for heroism and tragedy—for U.S. soldiers and the indigenous Vietnamese soldiers and civilians with whom he worked. Each page is an accounting of who did what, how it was done, why it was done, and the outcome—good and bad. It is easy to understand why this update to the original 2007 edition was necessary. One can only imagine the volume of correspondence Parnar and Dumont received from Vietnam veterans acknowledging his story—adding details and validation. Additional maps and photos add to the fuller picture.

Parnar’s recollections of his Army enlistment are replete with self-examination and lessons he learned. He made mistakes and was smart enough to recognize them when they happened—taking corrective action to ensure they didn’t happen again. He recognized good leadership when he saw it and emulated it when he could. That’s reason enough to read this book.

As a medical company commander in the 25th Infantry Division in 1984, my first sergeant was a seasoned combat veteran who had served as a combat medic in Vietnam. 1st Sgt. Bob Carpenter was all you would hope for in a “top”—professional, sage, patient, disciplined and a good coach. I don’t recall that we talked much of his combat experiences, but in hindsight I realize how Vietnam helped shape him into the leader he was. Parnar’s ability to relate detailed, personal experiences provides me with a better understanding of what Carpenter experienced in Vietnam.

Parnar’s accounting of his Vietnam experience may only be one soldier’s story, but it has given me a fuller appreciation for what it meant to serve in Vietnam. The service, sacrifice and valor of a generation are vividly documented in the pages of SOG Medic.

Col. Leif G. Johnson, U.S. Army retired, served more than 26 years in the medical service corps, commanding at every level from medical company to medical group.

* * *

Fierce Fighting for an Insurgent Stronghold

Operation Medusa: The Furious Battle That Saved Afghanistan from the Taliban. David Fraser and Brian Hanington. McClelland & Stewart. 272 pages. $24

By Col. David D. Haught, U.S. Army retired

Retired Maj. Gen. David Fraser and journalist and author Brian Hanington, both Canadians, offer a detailed accounting of the events leading to, and the conduct of, Operation Medusa. Led by Fraser, Operation Medusa was the name for a NATO operation in Panjwai, a Taliban stronghold in Kandahar Province during the Afghanistan War.

The objective of the operation was to defeat the Taliban in and around Panjwai in order to maintain freedom of movement along Highway 1 and uphold the security of Kandahar City.

Learning the night before of the Taliban’s intent to initiate offensive operations, Fraser and his staff were about to enter the largest fight for NATO in over 70 years. For 15 days in September 2006, members of the 1st Battalion, the Royal Canadian Regiment Battle Group, and elements of the International Security Assistance Force, supported by the Afghan National Army and a team from the U.S. Army’s 1st Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne), augmented by Company A, 2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry), engaged in intense close combat.

Also providing support were the U.K., the Netherlands and Denmark. According to Evan Dyer of the Canadian Broadcasting Corp., Operation Medusa at the time was the most significant land battle ever undertaken by NATO.

There is no question as to the credentials of the authors. Fraser was the commander of the operation. A 10-year veteran of the Canadian Navy, Hanington has published more than a dozen books and written for Canadian prime ministers, cabinet ministers, bishops, admirals and Pope John Paul II. Their motive in writing the book was simple. They wanted to tell a story—a story of intense combat, fought by an army and a nation that had not seen major combat operations since the Korean War, and supported by a government that was intent on making a valuable contribution to NATO and the mission in Kandahar Province. Fraser and Hanington do not betray their readers.

In great detail, Fraser and Hanington chronicle the events leading up to the fighting (Book One) and the tactical actions of Operation Medusa and the fight for the Panjwai district (Book Two), Sept. 2–17, 2006. Fraser and his troops were in an unenviable position. The Taliban knew the terrain. They had spent months preparing their defenses with pre-positioned supplies, land mines and IEDs. The enemy, protected by corrupt officials, amassed a worthy fighting force and was ready to face freshly arrived troops who had never seen combat.

Fraser and Hanington meticulously describe combat actions beginning with the loss of a U.K. Royal Air Force Nimrod surveillance aircraft with 14 crew members (only four hours into the fight) and ending with the clearance of Objective Baseball and the Taliban fleeing the area of operations. After 15 days of fighting, NATO declared victory and stability operations commenced Sept. 17.

The strength of the book is the ease with which Fraser and Hanington inform the reader of strategic implications of Canada assuming responsibility for Kandahar Province and the leadup to Operation Medusa, followed by close, intimate descriptions of the fighting in and around Panjwai and Zhari.

Students of the Afghanistan War, NATO operations, Canadian history and military operations, and those with an interest in battlefield histories, will find this a great read and a noteworthy addition to their library.

Col. David D. Haught, U.S. Army retired, is an assistant professor in the Department of Tactics, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Belvoir, Va., Satellite Campus. He served over 29 years in the Army as a field artillery officer with his final assignment as division chief, Joint Requirements and Assessments, Deputy Chief of Staff for Programs, Headquarters, Department of the Army, the Pentagon.

* * *

Ranger Offers Rare, Raw View of Combat

When the Killer Man Comes: Eliminating Terrorists as a Special Operations Sniper. Paul Martinez With George Galdorisi. St. Martin’s Press.

304 pages . $26.99

By Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer, U.S. Army retired

When the Killer Man Comes is an account of the day-to-day life of a 21st-century warrior. Written by retired Staff Sgt. Paul Martinez with co-author George Galdorisi, it offers the reader a rare glimpse into the inner workings of one of the most elite units in America’s Army, the 75th Ranger Regiment.

Martinez spent seven years assigned to the 75th’s 3rd Ranger Battalion, headquartered at Fort Benning, Ga., and he deployed six times to Afghanistan.

The regiment, part of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), has the mission of closing with and destroying the enemy. Its members are not trainers, advisers or nation-builders. It is a direct-action unit.

Combat has been described as “hours and hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.” Martinez paints a picture that makes the case about that description being true. An infantryman in combat in Afghanistan or any war has the most difficult and dangerous mission. Physical exhaustion, hunger, stress and sleep deprivation are constant companions for Rangers in combat. But once contact with the enemy is imminent, the adrenaline rush restores, at least temporarily.

Martinez shares his thoughts as he approaches an objective: “I’m on a helicopter full of Rangers, my face is covered with camo, and I have a sniper rifle. LIFE IS GOOD.”

Martinez started his Army career as a member of a 60 mm mortar crew. Just before his last deployment, he joined a Ranger task force sniper team. His marksmanship talent served him well in training. Despite his relative youth and inexperience, he graduated second in the Special Forces Sniper Course and a few weeks later he competed in the annual USASOC sniper competition, where he finished a close second.

There was little time to celebrate, however, because he was about to deploy to Afghanistan for his sixth rotation. This time was different. This time he was a member of the Ranger sniper team.

The Rangers conduct most of their combat operations at night. They don’t operate in the same area for long. The movement from one place in Afghanistan to another is not easy for the reader to follow. The book, unfortunately, does not include a map. On the other hand, the tactics and techniques used by the Rangers are easy to follow because the author tries to limit the use of military acronyms. The book will appeal to a wide range of readers: military, nonmilitary and anyone who is simply looking for an interesting addition to their reading list.

When the Killer Man Comes is not about the history of the war on terrorism. It’s not about politics or the conduct of its leaders. It’s about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. It’s about the bonding that takes place among soldiers in combat. Bonds forged in fire that last a lifetime.

Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmie W. Spencer, U.S. Army retired, held assignments with infantry, Special Forces and Ranger units during his 32 years of active military service. He is the former director of the Association of the U.S. Army’s NCO and Soldier Programs and is an AUSA senior fellow.